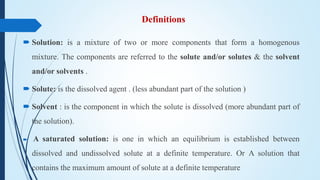

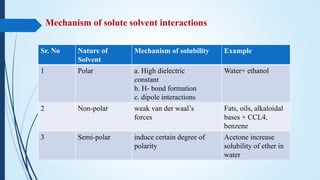

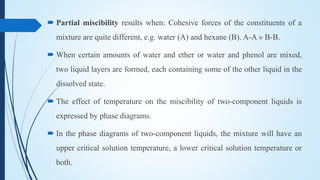

This document discusses the importance and definitions of solubility in pharmaceutical science. It defines key terms like solution, solute, solvent, saturated solution, and discusses the quantitative and qualitative ways of describing solubility. The document outlines factors that influence drug solubility like temperature, nature of solvent, pH, and particle size. It also discusses concepts like thermodynamic solubility, solubility expressions, solute-solvent interactions, and laws governing solubility like Raoult's law, ideal and non-ideal solutions, and distribution law.