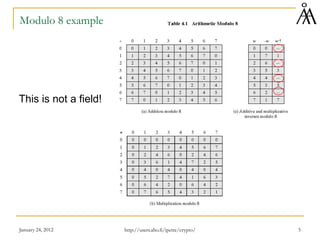

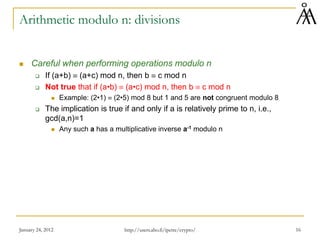

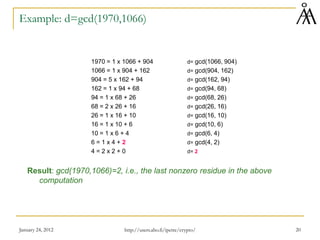

This document provides an overview of finite fields and their importance in cryptography. It discusses how finite fields allow for efficient storage and arithmetic operations on integers for encryption algorithms. The document outlines the basic properties of groups, rings, and fields. It also covers modular arithmetic, greatest common divisors, and Euclid's algorithm for computing gcd. The goal is to introduce concepts needed to understand the arithmetic of the AES encryption algorithm, which uses operations in the finite field GF(28).

![Content of this lecture

January 24, 2012 http://users.abo.fi/ipetre/crypto/ 2

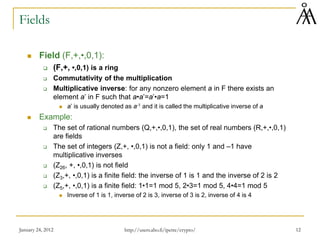

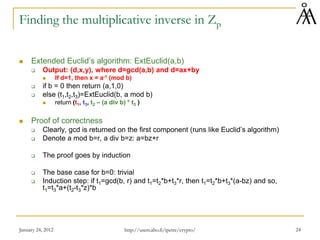

Z Zp

Zp[X] GF(pn)

Modular

arithmetics

Modular

arithmetics

Polynomials

Every finite field

has this structure

Domain of

operation

of AES](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sheet6-230423103235-8ad9681c/85/sheet6-pdf-2-320.jpg)

![January 24, 2012 7

Summary of the constructions in this lecture

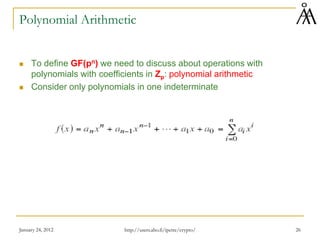

Consider the integers Z

Take a prime number p and do operations modulo p: Zp is a field with

p elements (order p)

Consider polynomials with coefficients in Zp: Zp[X]

Take an irreducible polynomial m(x) of degree n and do operations

modulo m(x): GF(pn) is a field with pn elements (order pn)

AES uses GF(28) with arithmetic modulo x8+x4+x3+x+1

http://users.abo.fi/ipetre/crypto/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sheet6-230423103235-8ad9681c/85/sheet6-pdf-7-320.jpg)

![January 24, 2012 27

Ordinary Polynomial Arithmetic

Consider polynomials with coefficients in a ring or a field – e.g, Z

Adding/subtracting two polynomials is done by adding/subtracting the

corresponding coefficients

Multiplying two polynomials is done in the usual way, by multiplying all terms

with each other

Division (not necessarily exact) of two polynomials can also be defined if the

coefficients are in a field

Example: f(x) = x3 + x2 + 2, g(x) = x2 – x + 1 with coefficients in Z

f(x) + g(x) = x3 + 2x2 – x + 3

f(x) – g(x) = x3 + x + 1

f(x) x g(x) = x5 + 3x2 – 2x + 2

For a ring or a field R, (R[X],+,•,0,1) is a ring – the ring of polynomials over R

http://users.abo.fi/ipetre/crypto/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sheet6-230423103235-8ad9681c/85/sheet6-pdf-27-320.jpg)

![January 24, 2012 30

Computing the GCD of two polynomials over Zp

Euclid(a,b)

If b=0 then return a

Else return Euclid(b,a mod b)

EUCLID[a(x), b(x)]: computes gcd(a(x), b(x))

If b(x)=0 then return a(x)

Else return EUCLID(b(x), a(x) mod b(x))

http://users.abo.fi/ipetre/crypto/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sheet6-230423103235-8ad9681c/85/sheet6-pdf-30-320.jpg)

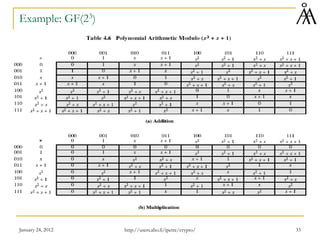

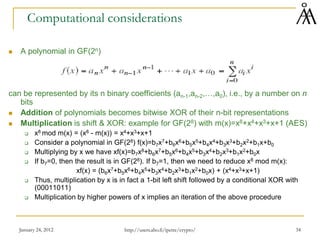

![January 24, 2012 31

Modular Polynomial Arithmetic

(arithmetic modulo a polynomial)

Consider an irreducible polynomial f(x) with degree n and coefficients in Zp

Example: x8+x4+x3+x+1 is irreducible in Z2[x] (the polynomial used in AES)

Polynomial arithmetic modulo f(x) can be done similarly as integer arithmetic

modulo a prime number p

Take any two polynomials modulo f(x)

Do addition/subtraction/multiplication modulo f(x)

If f(x) is irreducible, then the set of all polynomials modulo f(x) forms a field

denoted GF(pn)

We are mostly interested in GF(2n) : all polynomials with binary coefficients

and degree less than n

Addition is the normal addition of two polynomials

Multiplication is done modulo f(x)

GF(2n) is indeed a field: any nonzero element has an inverse

The extended Euclid algorithm can be used here just like for integers

http://users.abo.fi/ipetre/crypto/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sheet6-230423103235-8ad9681c/85/sheet6-pdf-31-320.jpg)

![January 24, 2012 35

Summary

Consider the integers Z

Take a prime number and do operations modulo p: Zp is a field with p

elements (order p)

Consider polynomials with coefficients in Zp: Zp[X]

Take an irreducible polynomial m(x) of degree n and do operations

modulo m(x): GF(pn) is a field with pn elements (order pn)

Any finite field has order pn, for some prime p and a positive integer n

AES uses GF(28) with arithmetic modulo x8+x4+x3+x+1

http://users.abo.fi/ipetre/crypto/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/sheet6-230423103235-8ad9681c/85/sheet6-pdf-35-320.jpg)