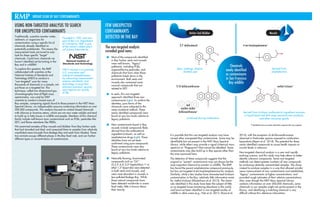

Scientists used non-targeted analysis to screen wildlife samples from San Francisco Bay for unmonitored contaminants. This technique identified five contaminants not previously found in Bay wildlife, including compounds derived from triclosan and amphetamines in mussels and dichloroanthracenes in harbor seal blubber. However, most contaminants detected were legacy pollutants already monitored by the Regional Monitoring Program. The detection of a few new contaminants suggests monitoring should expand to related compounds as well.