This document reviews applied behavioral research focusing on functional analysis (FA) in public school settings, highlighting necessary modifications to traditional FA procedures due to the unique challenges of these environments. It discusses changes to experimental designs, antecedent, and consequent conditions to improve the validity and applicability of interventions for problem behaviors in schools. The review emphasizes the importance of adapting methodologies to ensure effective behavior assessments and interventions in naturalistic educational contexts.

![105-17, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), in

1997 mandated that a

‘functional behavioral assessment’ be conducted on students

who exhibit significant

behavior and adjustment problems. For at least these reasons,

FA research has moved

beyond the tightly controlled laboratory setting and into more

natural environments

involving more diverse populations. Development of behavioral

assessments of

problem behavior in school settings had empirical roots—for

example, 36 years ago

Thomas, Becker, and Armstrong (1968) noted that classroom

teacher’s disapproval

increased rates of student’s disruptive behavior. These

assessments allowed effective

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

*Correspondence to: Janet Ellis, Department of Behavior

Analysis, University of North Texas, P.O. Box 310919,

Denton, TX 76203-0919, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-3-320.jpg)

![/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-4-320.jpg)

![characteristics; and artificiality of

many of the settings in which FAs have been conducted. By

modifying the specifics

of various FA conditions or adding new conditions, each of

these issues could be

directly addressed.

206 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-8-320.jpg)

![FA to assess in-school problem behavior have been met with

several challenges

requiring modifications to standard analog FA procedures.

These challenges include

unwillingness on the part of school administrators and

classroom personnel to allow

experimental analyses that explicitly set the occasion for high

rates of problem

behavior. Likewise, Iwata (1996) noted that, ‘Some clients have

unusual histories that

may require modifications to the [general set of] conditions or

the addition of new

conditions’. Finally, systematic alteration of the analysis

conditions may be needed

‘if initial assessment data are unclear, consistency of

implementation has been

verified, and conditions have been attempted using the reversal

design . . . ’ (p. 2).

Conducting an FA of problem behaviors may require

consideration of a wider array

of antecedent and consequent variables, interacting antecedent

events, and complex

classes of behavior. The goal of modifying the standard methods

is to increase the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-11-320.jpg)

![nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-13-320.jpg)

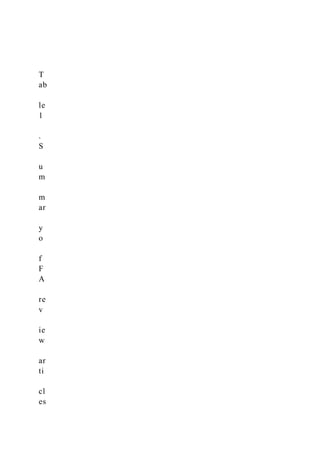

![ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense

design, changes to antecedent components and changes to

consequent components

(Table 1). Specific research studies exemplifying each of the

aforementioned

modifications are discussed below.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-18-320.jpg)

![iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-22-320.jpg)

![ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense

because during the course of this analysis corrective surgery

was being completed.

Despite these limitations, the FA findings led to an effective](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-46-320.jpg)

![compare an escape condition with a no-escape condition.

Results indicated that the

problem behavior was occasioned by the continuous

presentation of attention and

toys; however, the behavior did not appear sensitive to

contingent escape.

To compare brief and extended FAs of disruptive behavior,

Wallace and Knights

(2003) implemented a pairwise design followed by a

multielement design. The initial

pairwise design brief FAwas modified so that the conditions

were alternated as follows:

attention–control, demand–control, ignore–control. This brief

pairwise FA was

followed by an extended FA in which these same conditions

were alternated in the

standard order within a multielement design. This comparison

demonstrated that brief

FAs (i.e. 36 min total) ‘ . . . can be effective [when compared to

extended analyses—i.e.

310 min total] in identifying maintaining variables of disruptive

behavior . . . ’ (p. 126).

ANTECEDENT COMPONENT MODIFICATIONS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-48-320.jpg)

![iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-50-320.jpg)

![from demands. One

participant’s problem behavior occurred at the highest rates

during conditions with

low demands (LDI and LDA), which the authors stated could be

indicative of

boredom or an undifferentiated behavior pattern. Although

authors suggested that

212 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-54-320.jpg)

![nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-59-320.jpg)

![FA conditions. ‘For all

3 students, contingency reversals resulted in near zero

occurrences of target

behaviors . . . [and] . . . a corresponding increase in academic

work completion and

accuracy . . . ’ (p. 161).

Broussard and Northup (1997) conducted FAs in regular

education classrooms

with four students. Because classroom observations indicated

that teacher attention,

peer attention, and escape from demands were likely to follow

disruptive behavior,

these three conditions were implemented with each student.

Tasks were included in

all three conditions as follows: teacher and peer attention

conditions included

assignments previously completed with at least 90% accuracy,

whereas the escape

condition included assignments previously completed with less

than 50% accuracy.

As this study sought to evaluate the effectiveness of

intervention techniques aimed at

decreasing disruptive behavior and increasing on-task behavior,

data were collected](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-61-320.jpg)

![nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense

contingent on the hand-raise/disruptive sequence and delivered

praise with assis-

tance contingent on hand raises without disruptive behavior.

During the planned

ignoring condition teachers continued the hand-raise-without-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-64-320.jpg)

![noncompliance.

Modifications to basic functional analysis procedures 215

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-68-320.jpg)

![is generally assumed that separate topographies of a problem

behavior are members

of the same functional response class, this is not always the

case. At least

occasionally, occurrence of multiple topographies of a target

behavior maintained by

different reinforcers may have misrepresented FA outcomes. To

test this possibility,

authors conducted an aggregate analysis [multiple topographies

assessed simulta-

neously] of aberrant behavior, which indicated that both

stereotypy and self-injury

were maintained by sensory reinforcement. However,

subsequent separate analyses

of self-injury and stereotypy indicated these targets were a

function of two different

variables: escape maintained self-injury, whereas sensory

reinforcement accounted

for stereotypy.

FAs included these modified conditions: high sensory, in which

students were

exposed to non-contingent loud and constant noise while target

behavior was

ignored; and escape from high sensory condition, the same as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-71-320.jpg)

![nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense

Mace, Yankanich, and West (1988/1989) assessed potential

environmental

components of aberrant classroom behavior, stereotypy. The

authors state that rather

than ‘employing a set of standard conditions for most subjects,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-73-320.jpg)

![conditions [were]

developed which are idiosyncratic to a given student and his or

her educational

setting’ (p. 74). Student records, medical records, anecdotal

reports, and direct

observations led authors to predict antecedent conditions under

which high rates of

stereotypy would occur. In testing their predictions, four

modified FA conditions

were conducted.

In the playtime–no music condition target rates were measured

during unstructured

play in the classroom, an antecedent situation predicted to

evoke high rates. A second

condition, playtime–music, was identical except that easy

listening music played at a

moderate volume was introduced. This antecedent variable was

added after direct

observation indicated that it was associated with reduced rates

of stereotypy. A third

condition, playtime–music with headphones, was implemented

to determine whether

decreasing background noise while continuing to play music

would result in further](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-74-320.jpg)

![Modifications to basic functional analysis procedures 217

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-77-320.jpg)

![present and antibiotics were being administered, an absence-of-

symptoms condition

was carried out. Comparing target rates under these two

antecedent physiological

conditions revealed that mouthing was 21% more likely to occur

when infection

was present.

To assess potential drug–behavior interaction effects Northup et

al. (1997)

performed each of their conditions, teacher reprimand, peer

prompts, and time-out

with both medication (methylphenidate) and placebo. Outcomes

indicated that

‘ . . . (a) disruptive behavior was maintained by positive

reinforcement in the form of

peer attention and (b) methylphenidate functioned to alter

[reduce] either the saliency

of peers as [evocative] antecedent stimuli or the reinforcing

value of peer attention’

(p. 123).

Other Antecedents Evoking Target Behavior

While the standard FA demand condition involves repeated task

presentations,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-79-320.jpg)

![behavior. Broussard

and Northup (1995) state that ‘Current literature suggests three

variables as most

218 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-81-320.jpg)

![iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense

often related to classroom disruptive behavior: teacher

attention, peer attention, and

escape from academic demands’ (p. 152). Therefore, when

analyzing disruptive

classroom behavior of a student in regular education classes,

these authors added a

contingent peer attention condition to their analysis set. In this

condition two selected

peers joined the student participant in another classroom where

all three were

instructed to ‘Work quietly and complete these [academic]

worksheets’ (p. 157).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-82-320.jpg)

![nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-86-320.jpg)

![ons L

icense

peer attention resulted in a substantially higher percentage of

target behaviors than

did teacher attention’ (p. 227), indicating that peer attention

was the primary

reinforcer for target occurrences. Authors suggest that, ‘ . . .

peer and teacher attention

may not be functionally equivalent [and] that peer attention can

function as a unique

form of positive reinforcement’ (p. 228).

While assessing drug–behavior interaction effects, Northup et

al. (1997) included

what they referred to as a ‘peer prompts condition’ (p. 123).

Similar to previous peer

attention conditions described above, a peer ‘confederate’ was

instructed to speak to

the student participant if he left his seat or talked. The students

were each given

worksheets and instructed to stay seated and work quietly. The

disruptive behavior

occurred primarily during the peer attention sessions when the

student participant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-87-320.jpg)

![made contingent on SIB. Specifically, following each instance

of SIB the therapist

provided 30 s access to juice, saying ‘You must want your

juice’. Higher rates of SIB

occurred ‘ . . . during attention and tangible conditions than in

the other functional

analysis conditions’. (p. 284). Authors state that this outcome ‘

. . . appear[s] to

220 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-90-320.jpg)

![Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-95-320.jpg)

![ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om

m

ons L

icense

this condition was identical to the attention condition except

that instead of making

statements of disapproval, the therapist placed him face down

on the floor, holding

his arms for 10 s contingent on target occurrence(s). For student

participant 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-100-320.jpg)

![ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W

iley O

nline L

ibrary for rules of use; O

A

articles are governed by the applicable C

reative C

om](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-104-320.jpg)

![among school personnel, but may also enable other school

professional staff (e.g.

school psychologists, school diagnosticians, etc.) to make use of

these procedures.

Heeding Axelrod’s (1987) warning, and acknowledging that in

some cases school

personnel have neither the time nor the training to carry out

FAs, behavior analysts

224 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-108-320.jpg)

![assessments of attention as a reinforcer.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 463–477.

Broussard, C. D., & Northup, J. (1995). An approach to

functional assessment and analysis of

disruptive behavior in regular education classrooms. School

Psychology Quarterly, 10,

151–164.

Modifications to basic functional analysis procedures 225

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-112-320.jpg)

![Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 313–316.

Magee, S. K., & Ellis, J. (2001). The detrimental effects of

physical restraint as a consequence for

inappropriate classroom behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior

Analysis, 34, 501–504.

226 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-117-320.jpg)

![of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33,

207–221.

Modifications to basic functional analysis procedures 227

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term

s-and-conditions) on W](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-122-320.jpg)

![Zimmerman, E. H., & Zimmerman, J. (1962). The alternation of

behavior in a special classroom

situation. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 5,

59–60.

228 J. Ellis and S. Magee

Copyright # 2004 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Behav. Intervent. 19:

205–228 (2004)

1099078x, 2004, 3, D

ow

nloaded from

https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/doi/10.1002/bin.161 by B

ehavior A

nalyst C

ertification, W

iley O

nline L

ibrary on [14/11/2022]. See the T

erm

s and C

onditions (https://onlinelibrary.w

iley.com

/term](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/selectingimplementinginterventionsassignment4-221119013414-20f979bc/85/Selecting-Implementing-Interventions-Assignment-4-docx-124-320.jpg)