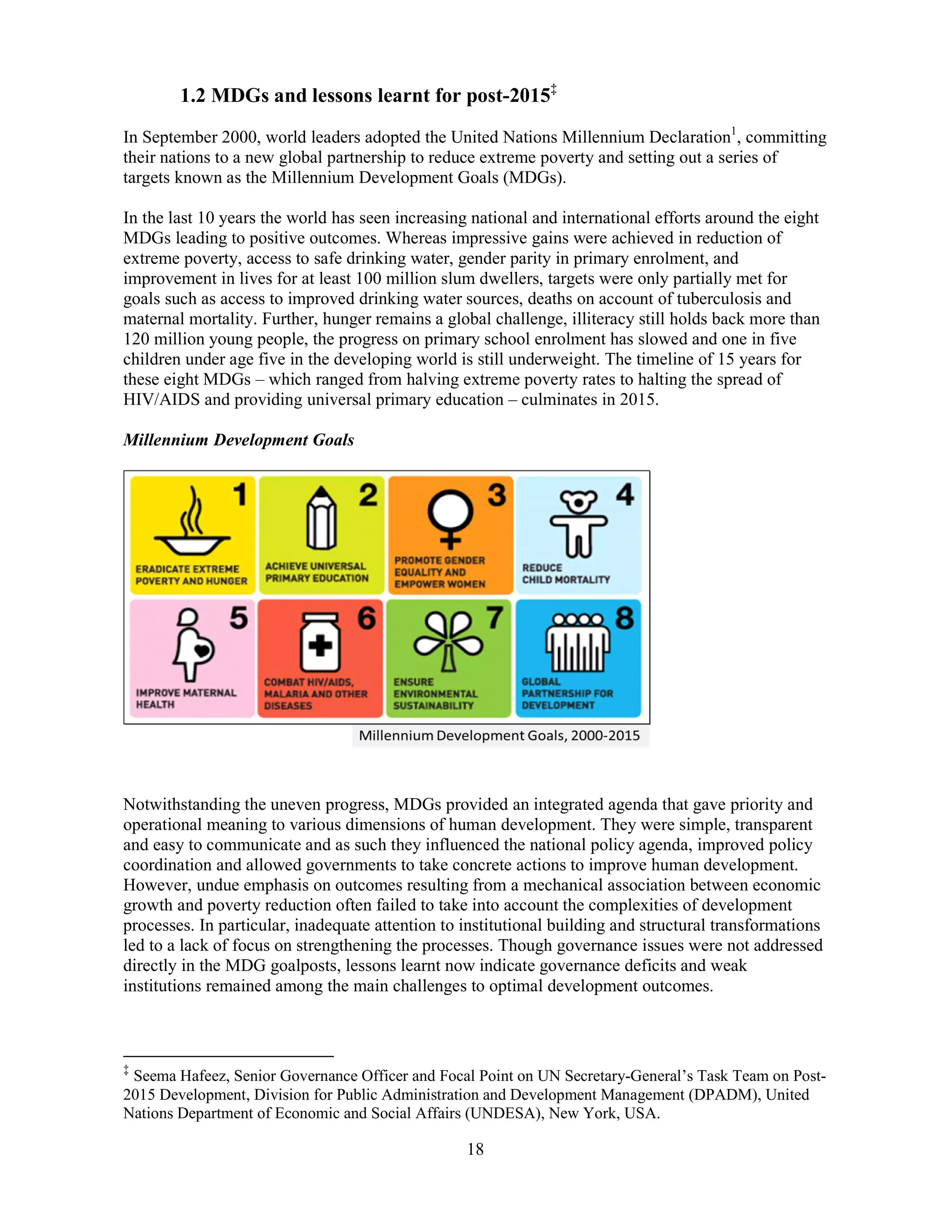

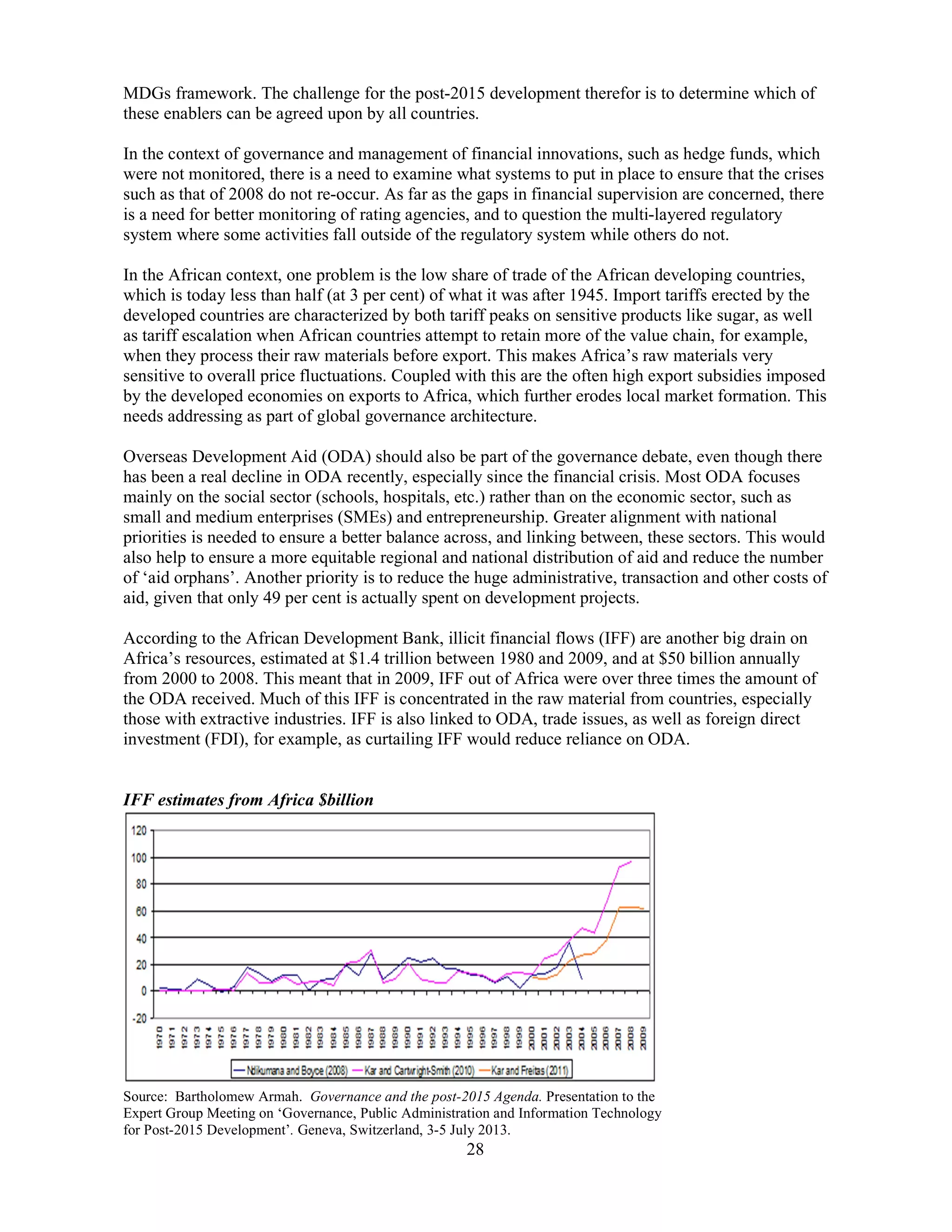

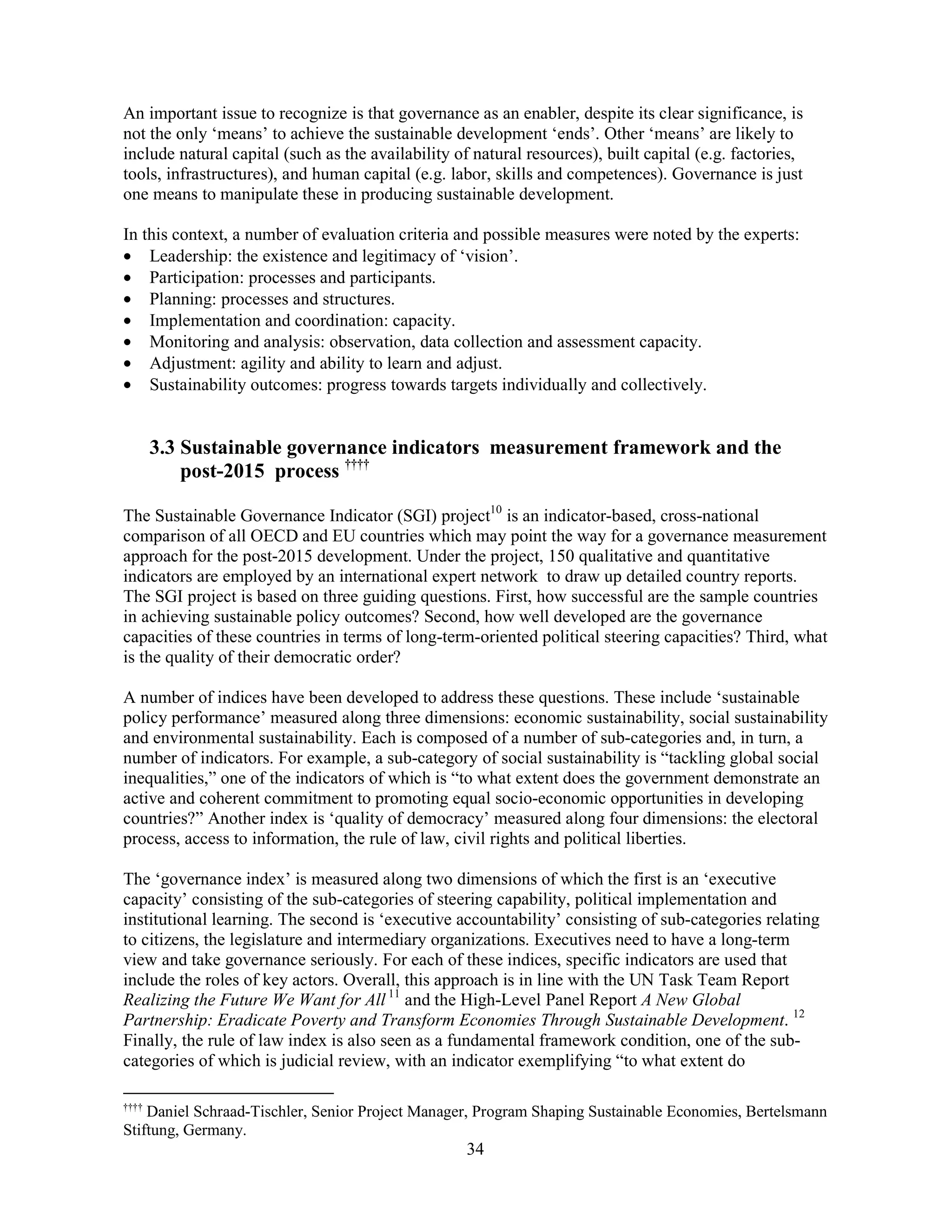

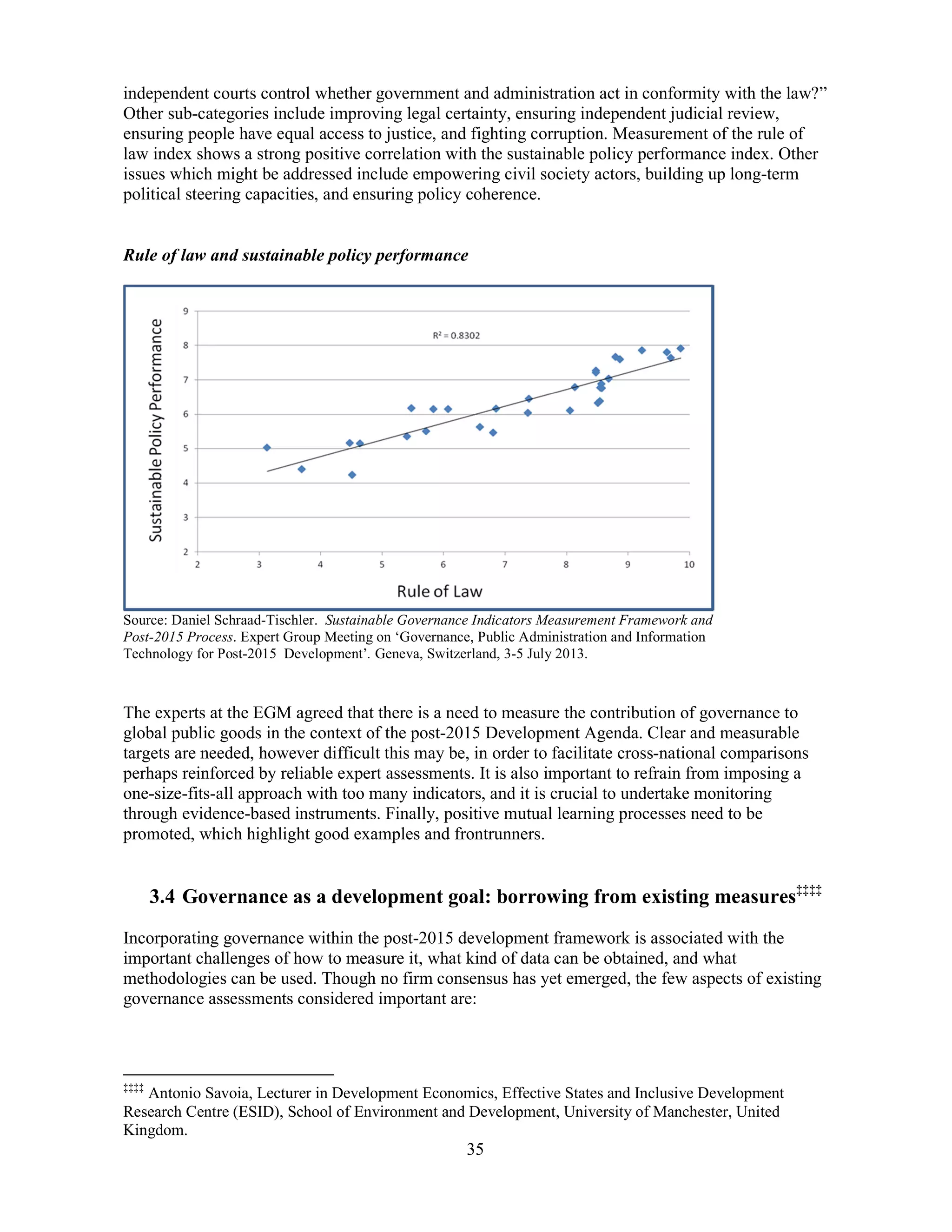

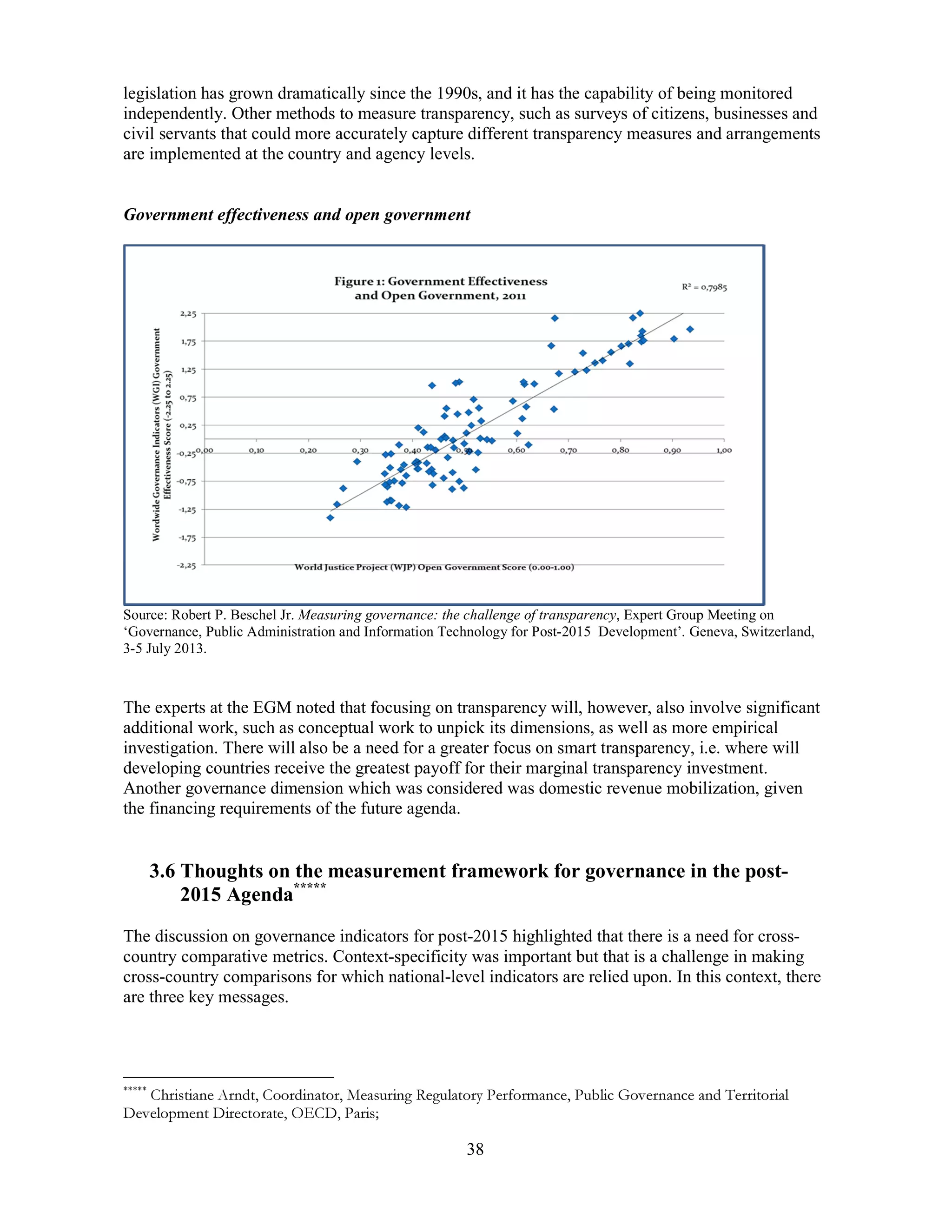

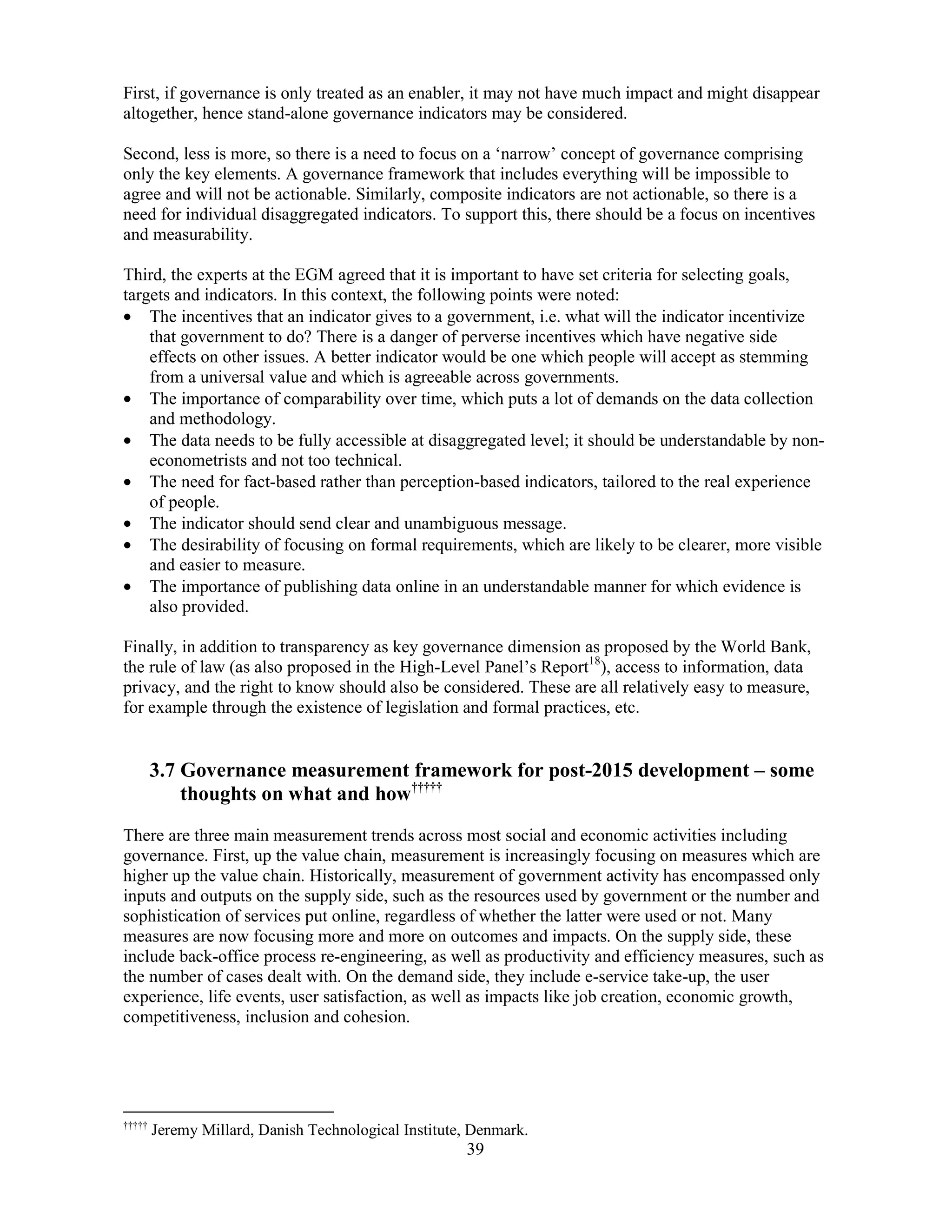

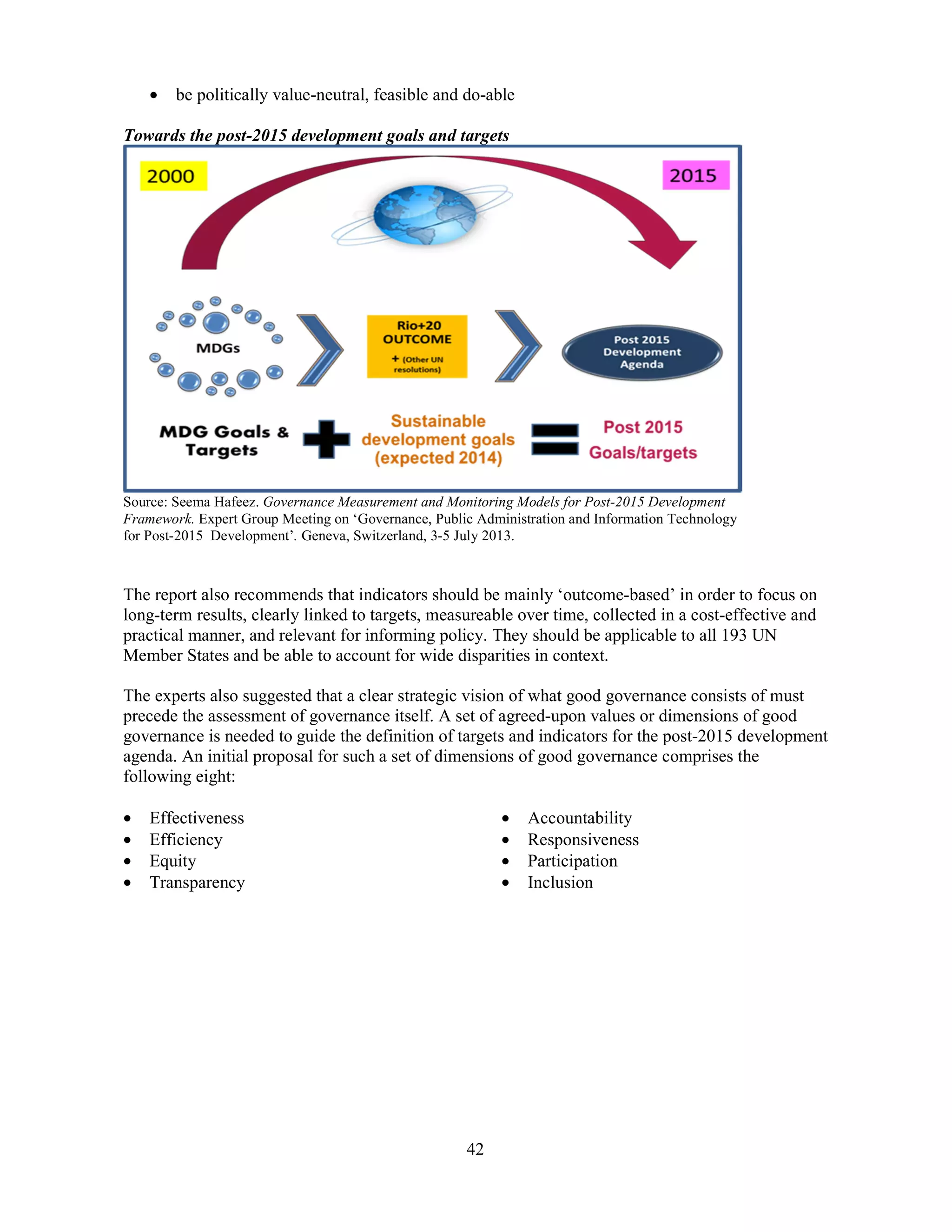

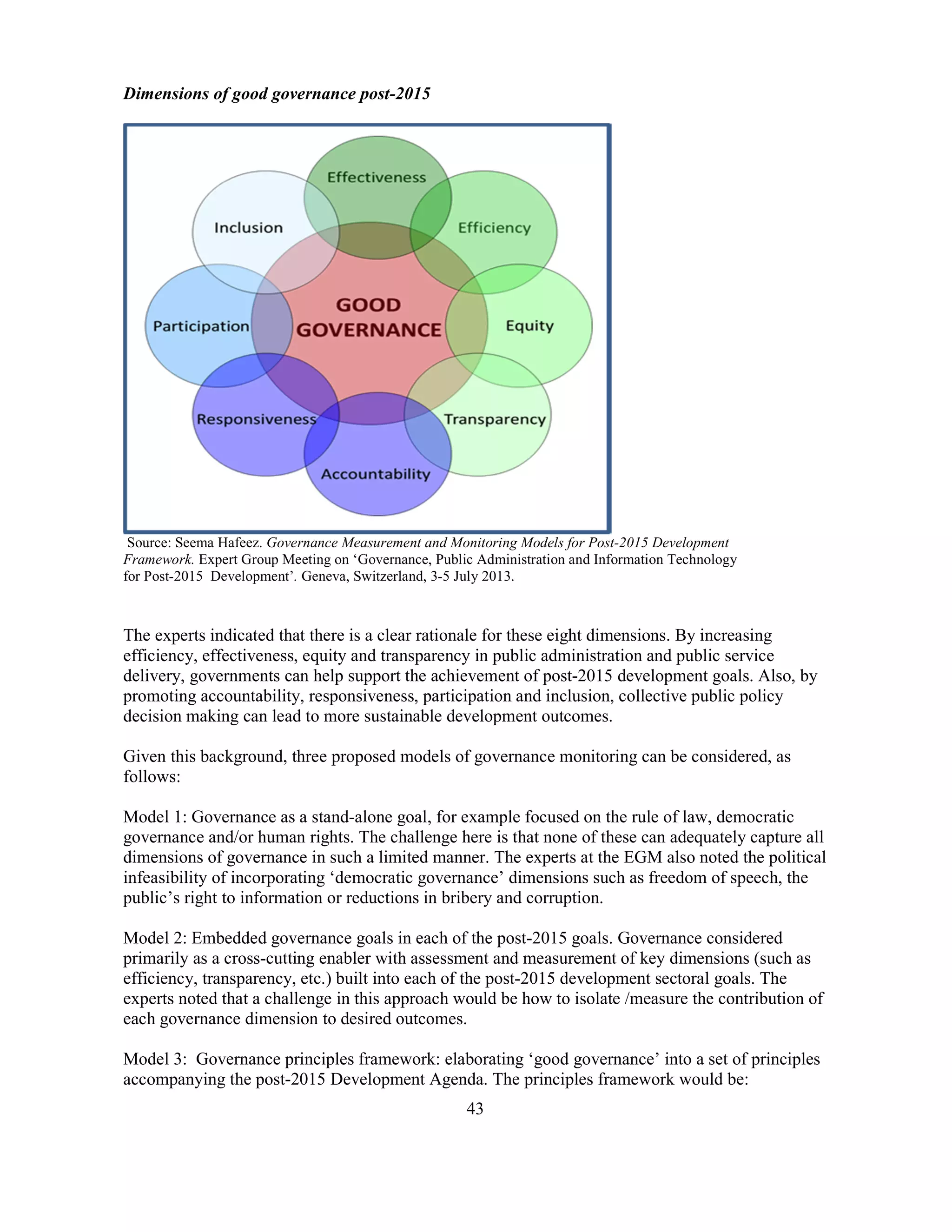

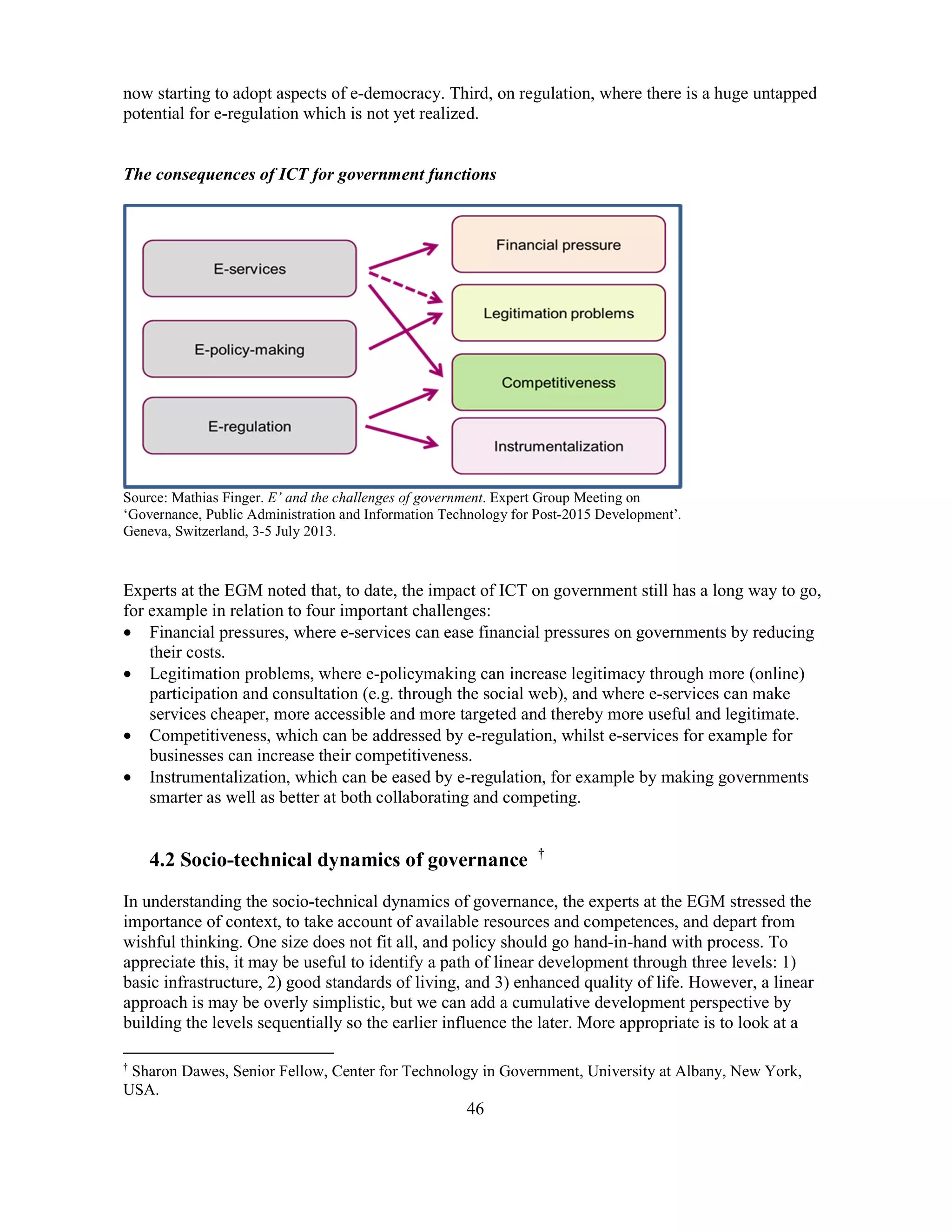

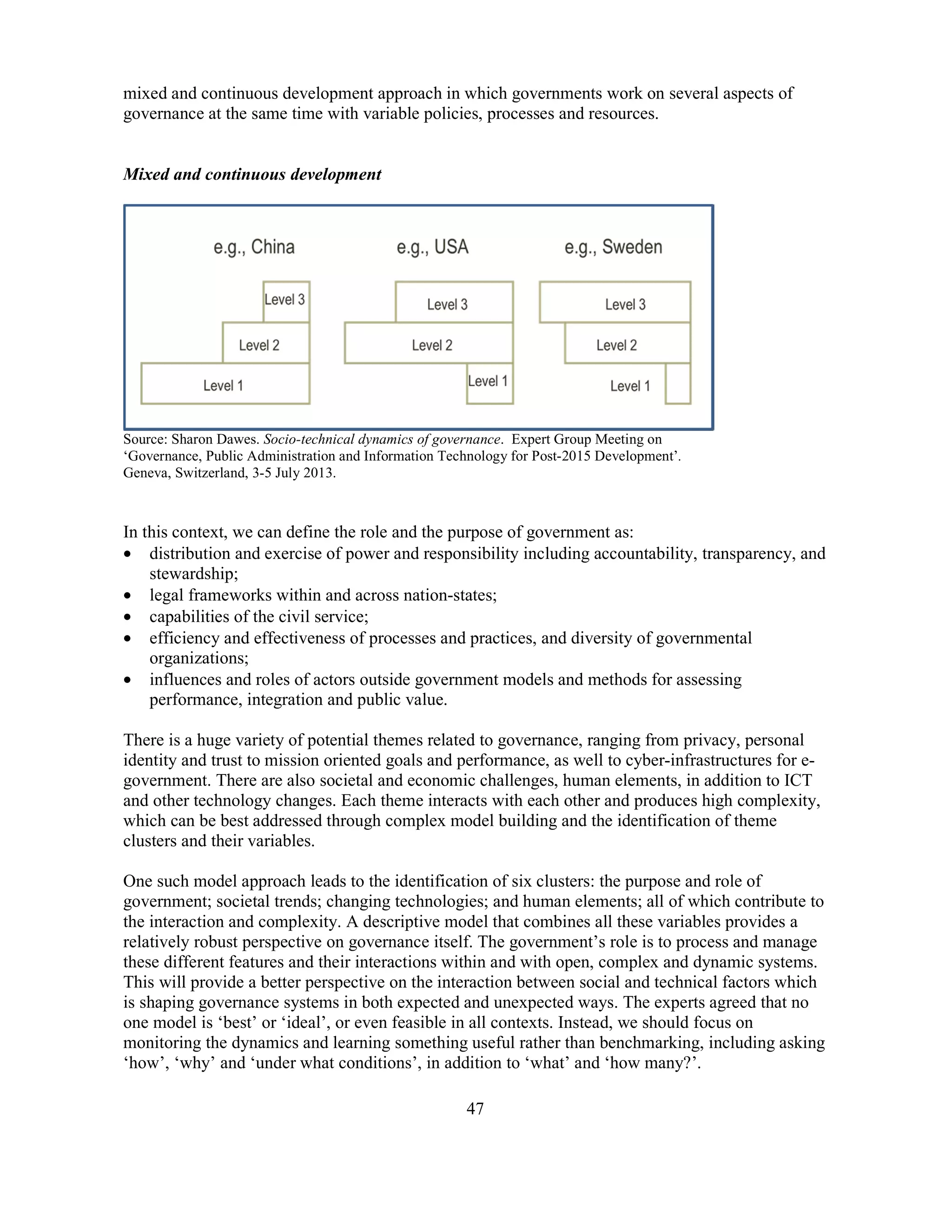

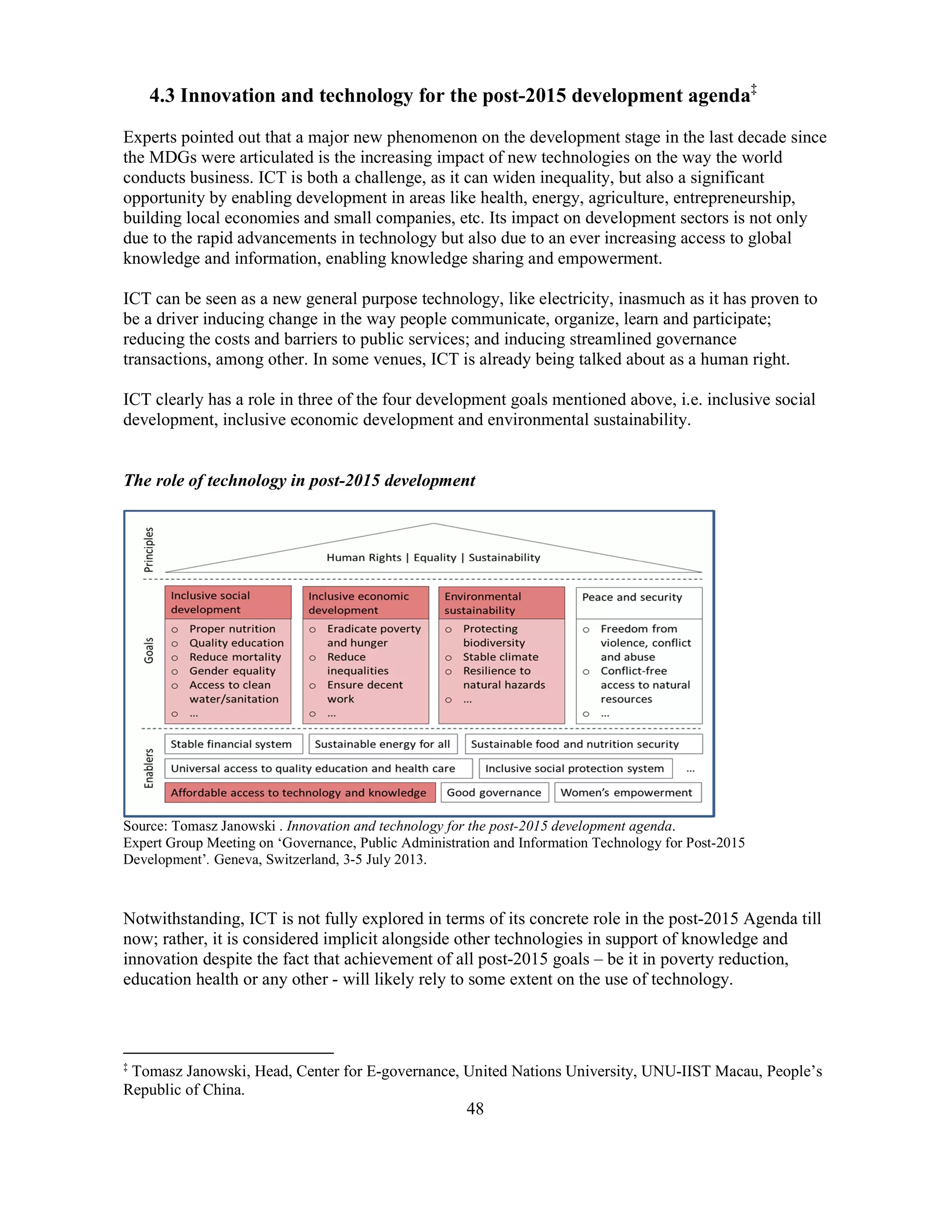

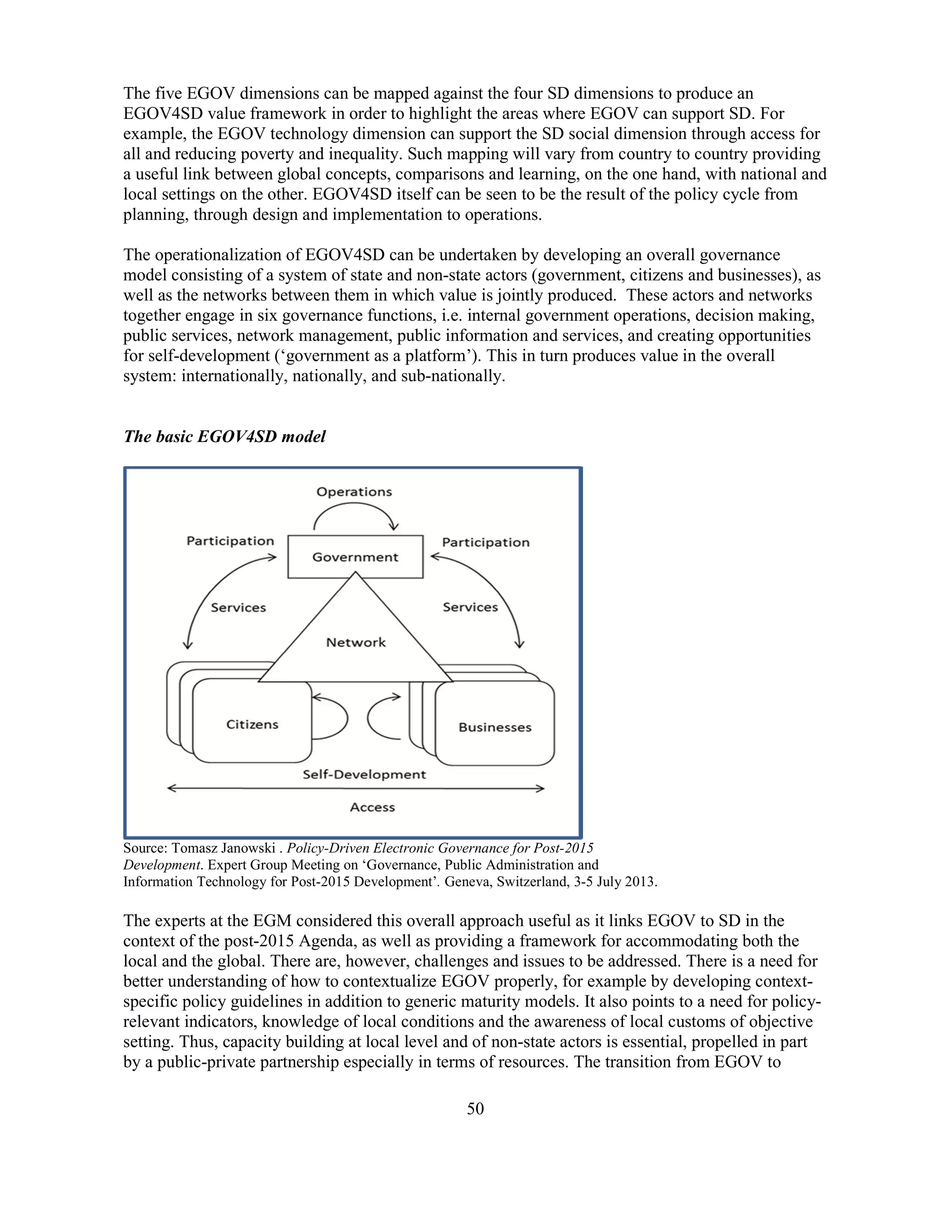

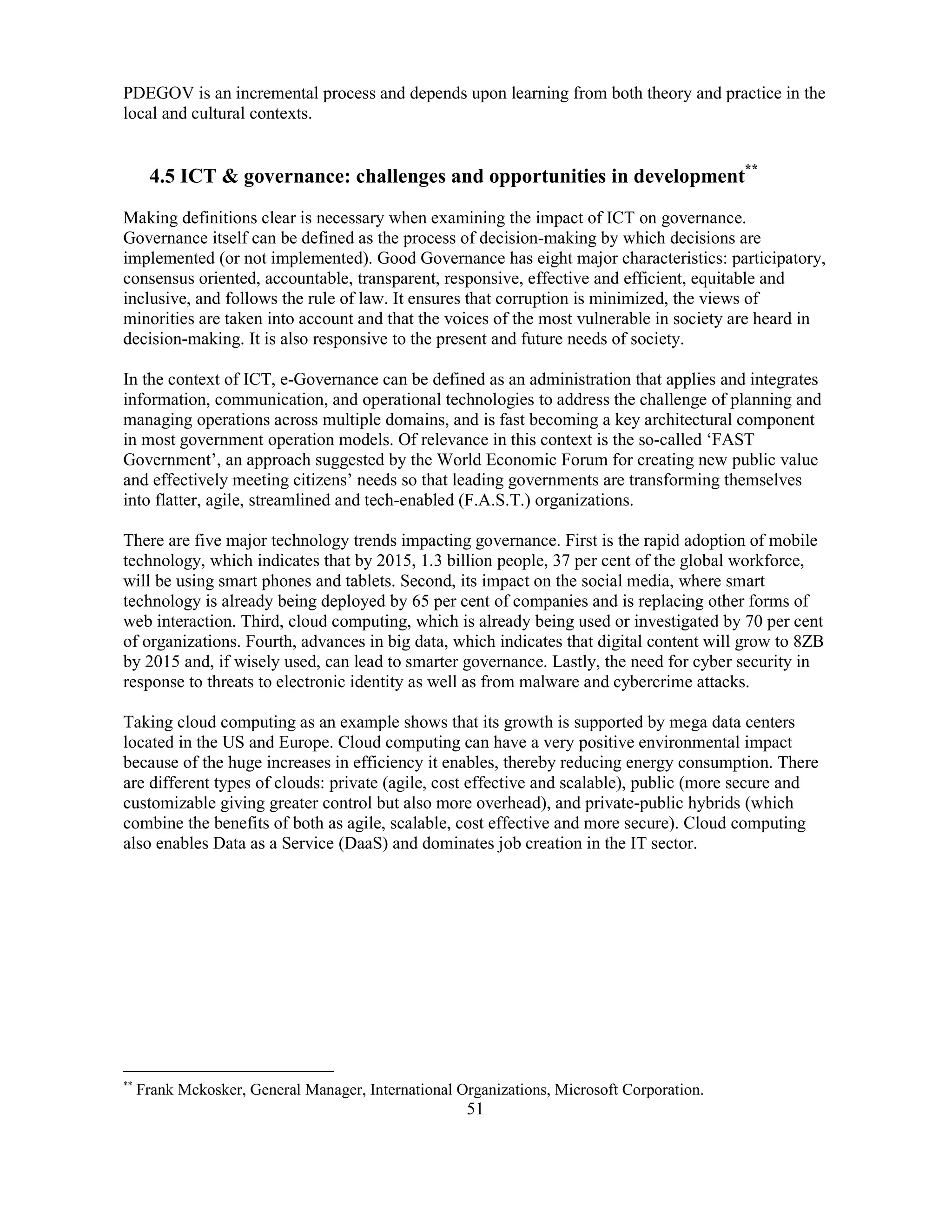

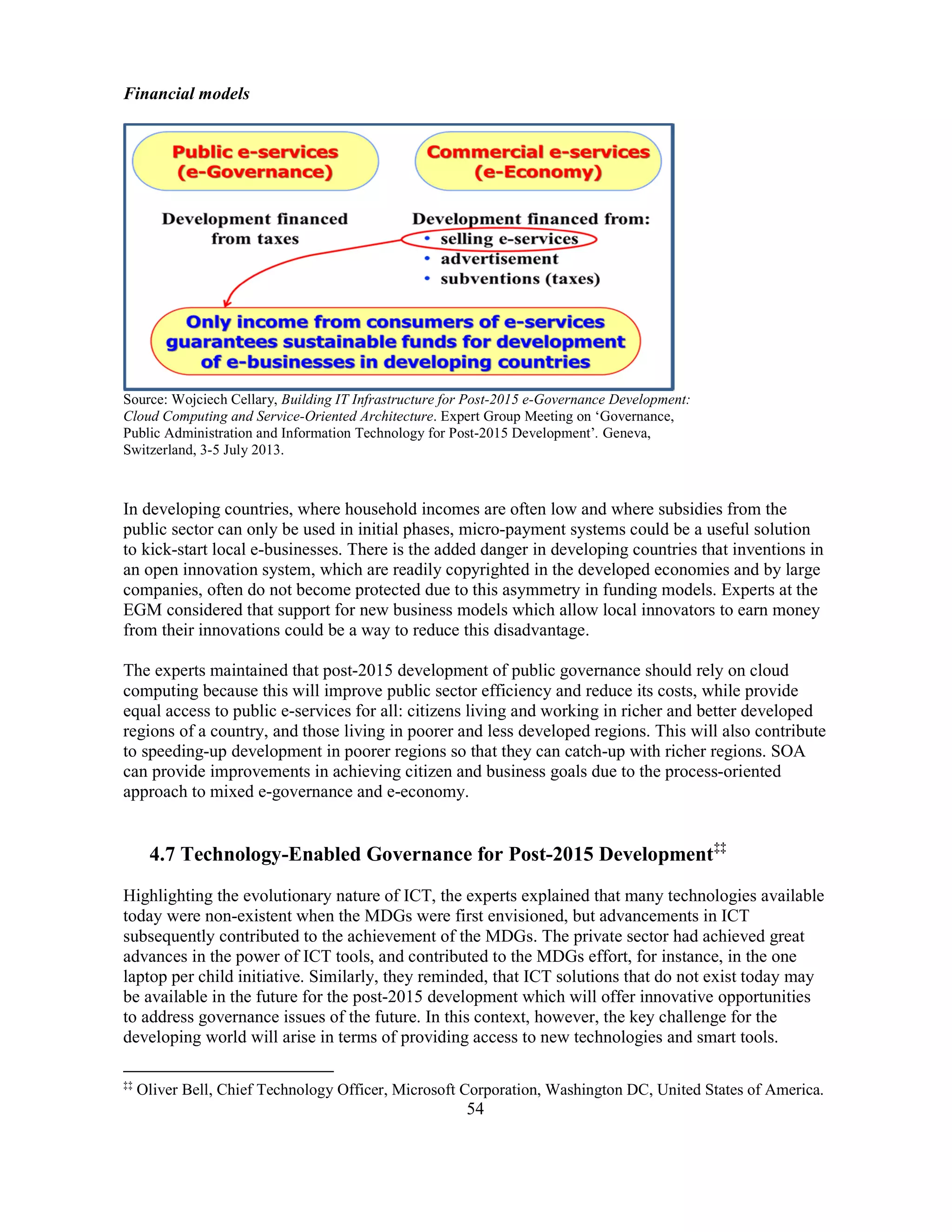

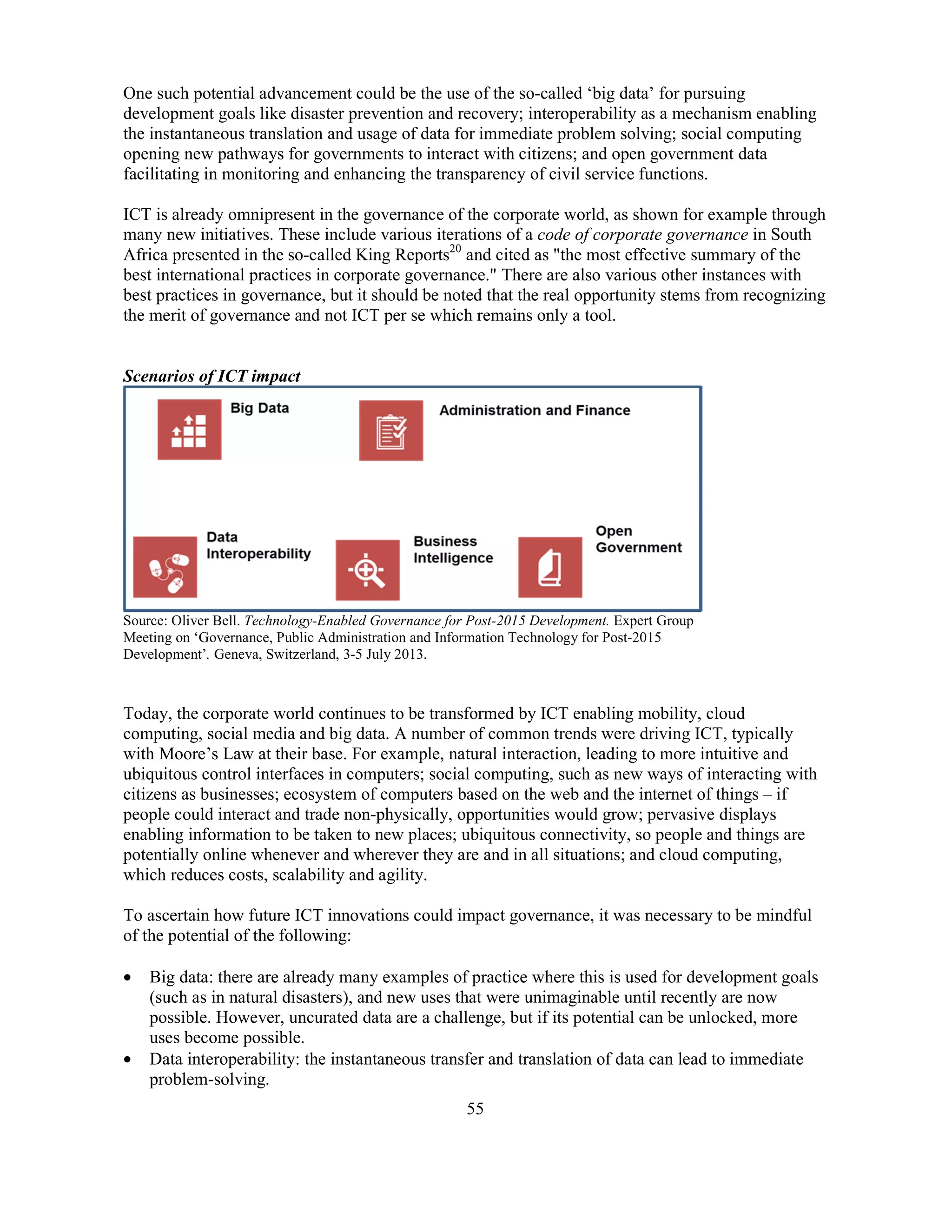

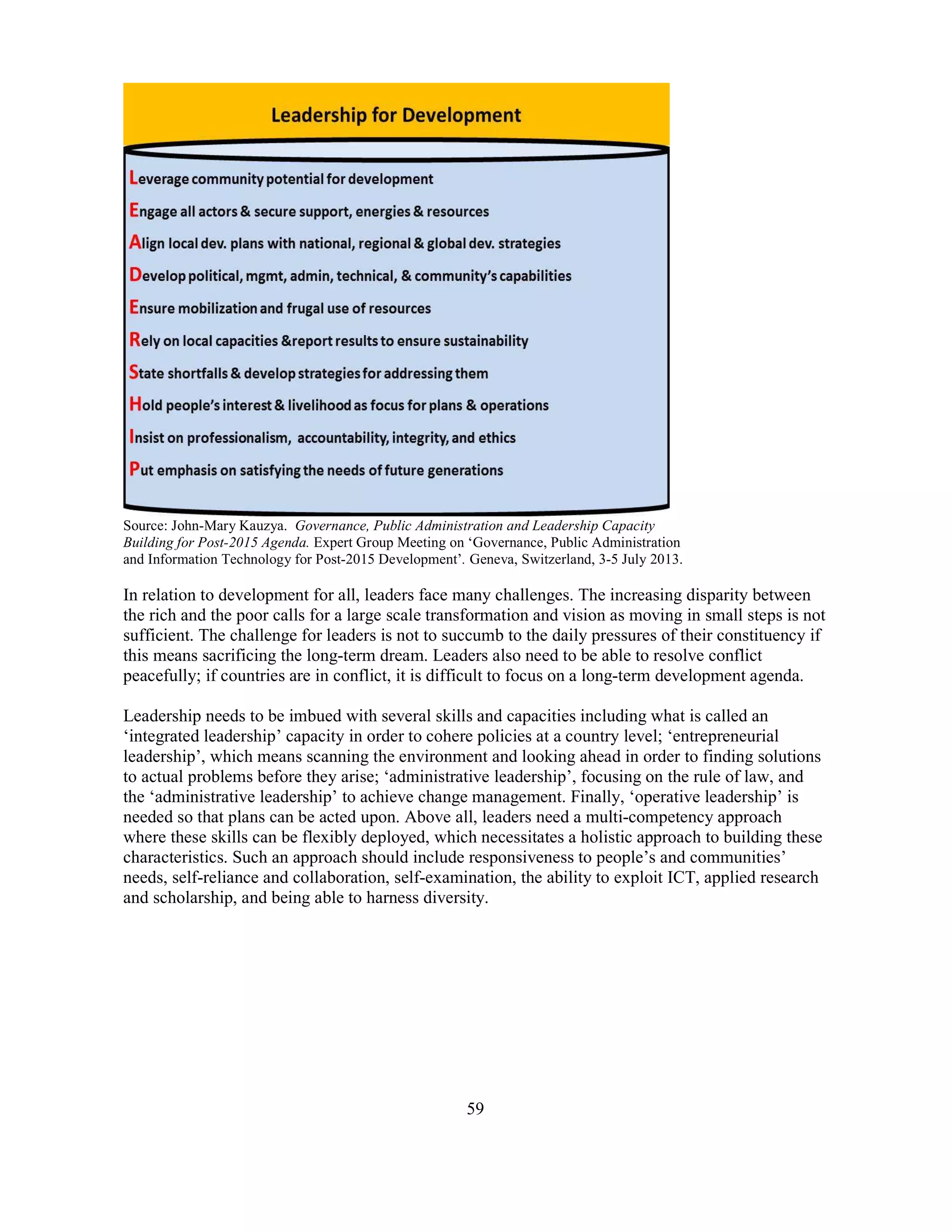

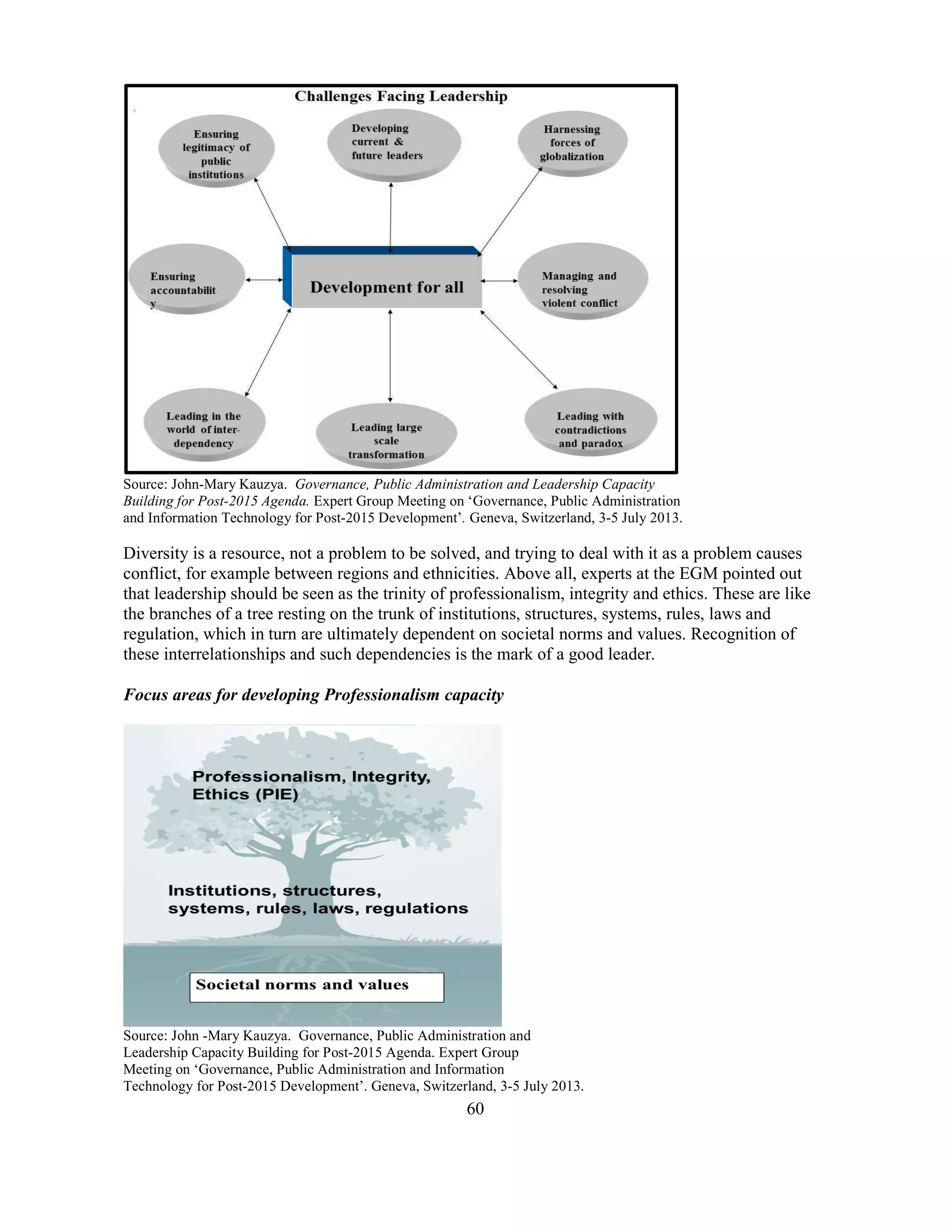

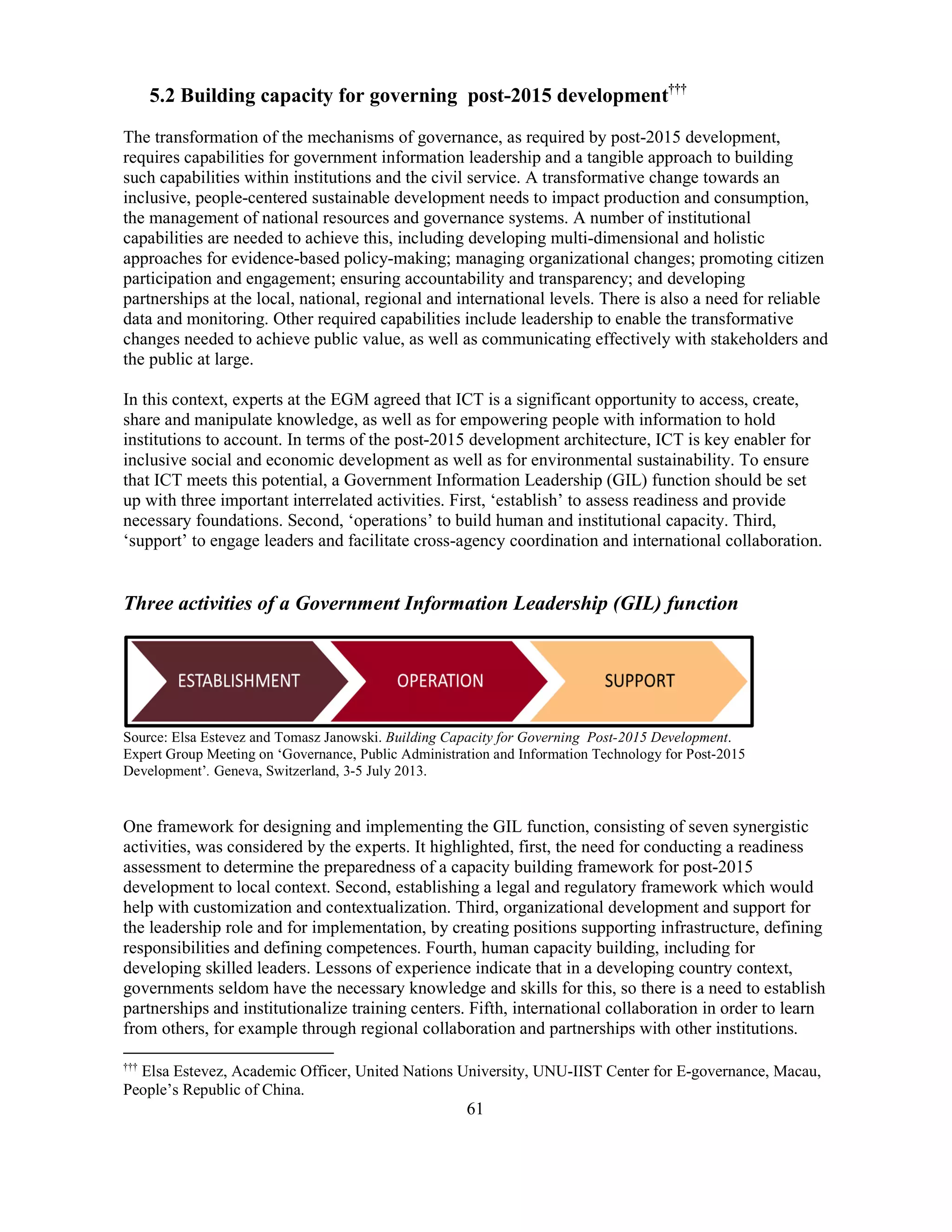

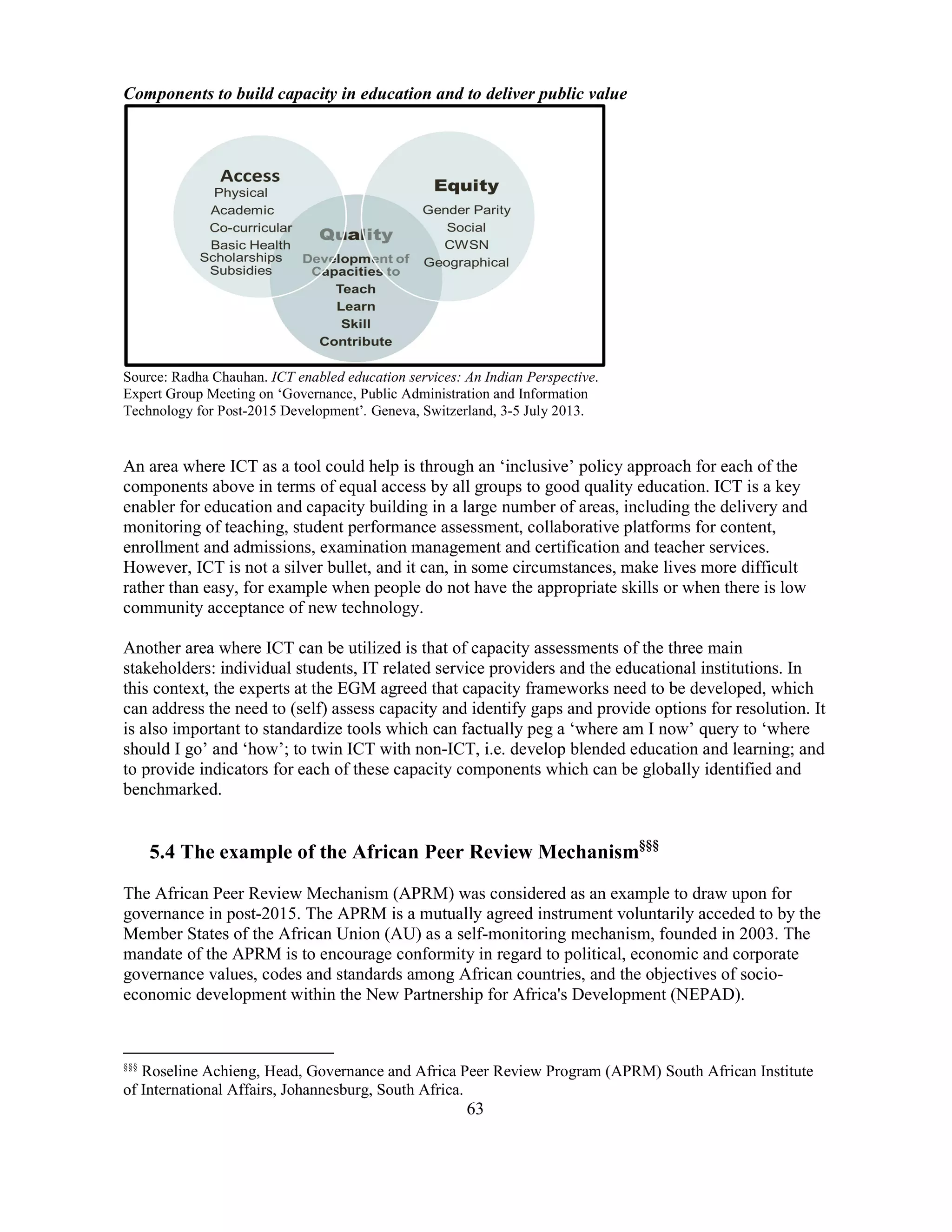

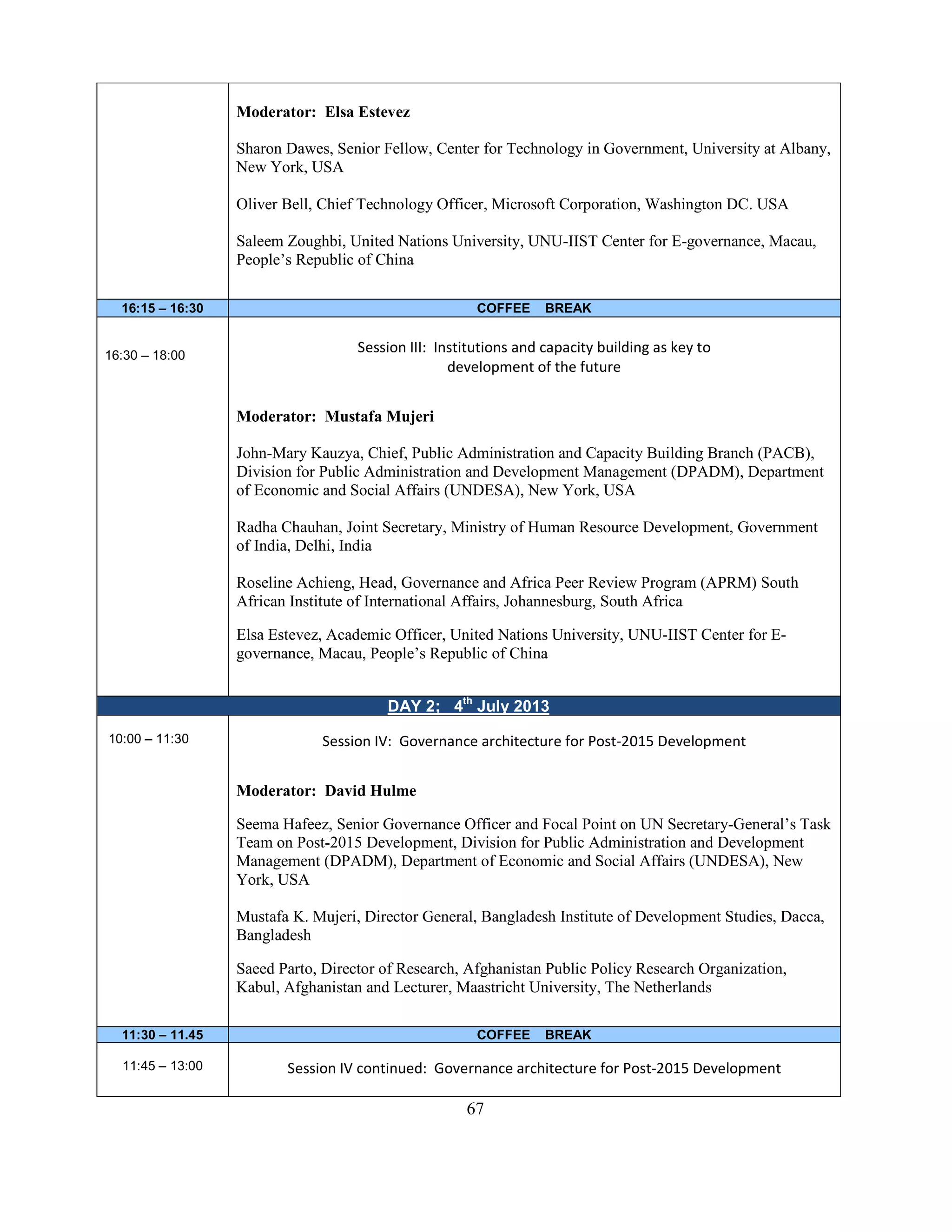

The report discusses the findings from an expert group meeting on governance, public administration, and information technology for post-2015 development, organized by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. It emphasizes the necessity of good governance as a critical enabler for sustainable development and identifies key issues and challenges for integrating governance into the post-2015 development agenda. The document advocates for an integrated governance framework centered around sustainability, supported by technology, to enhance accountability and transparency in the public sector.