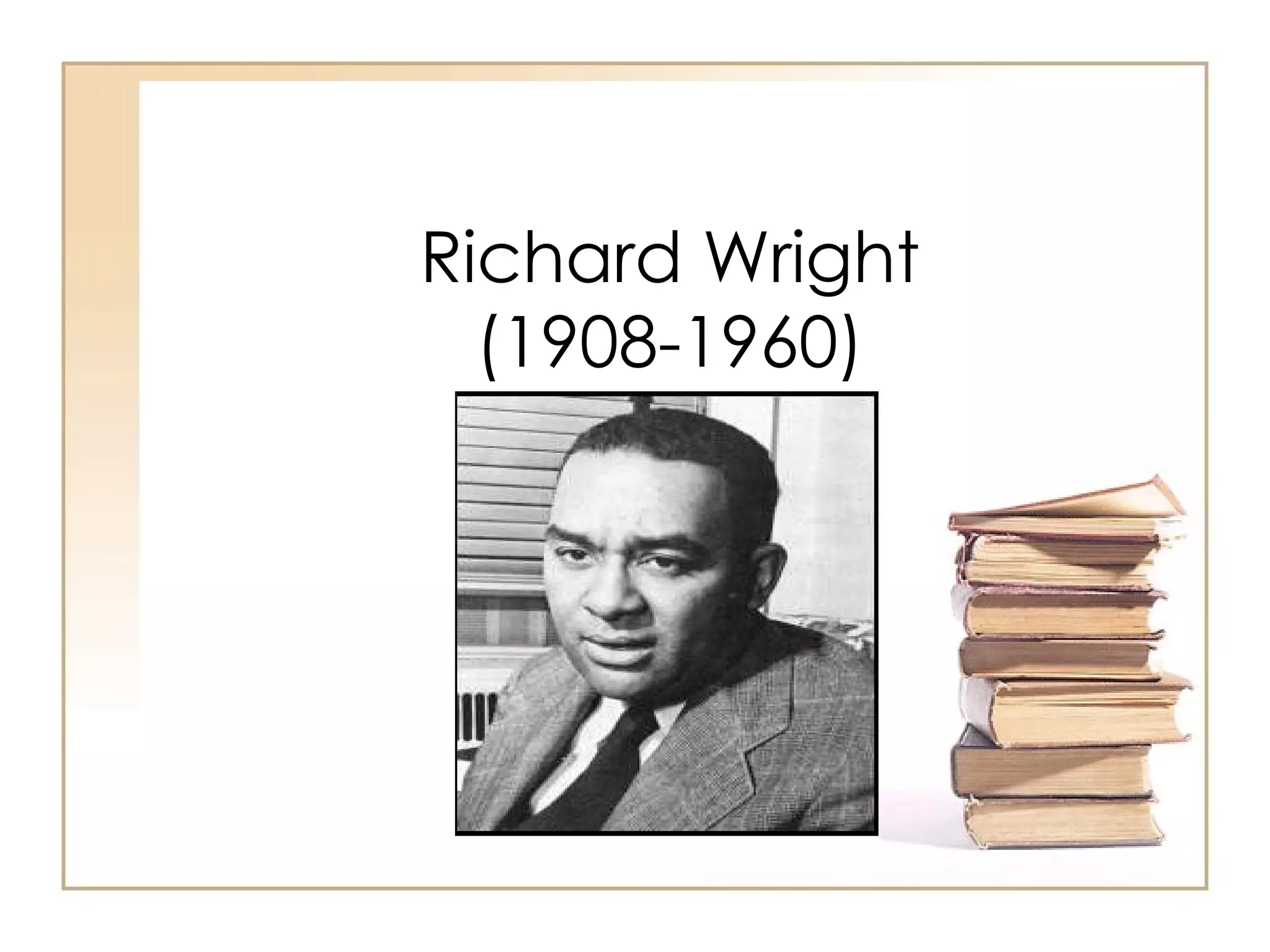

Richard Wright was an influential African American author born in 1908 in Mississippi. He had a fascination with literature from a young age. In his early adulthood, he moved to Chicago and supported himself with various jobs during the Great Depression. He joined the Communist Party and became a leader in the literary movement known as the "school for social protest." His novels Native Son and Black Boy brought him great acclaim and addressed issues of racism and oppression through Marxist themes. Wright later left the Communist Party and moved to France, where he died in 1960.