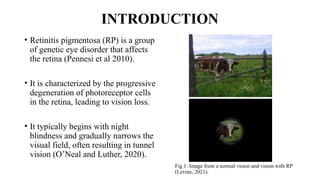

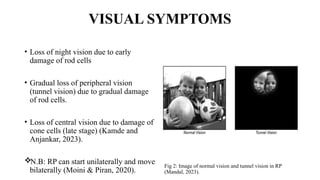

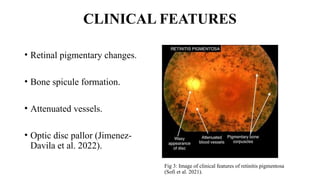

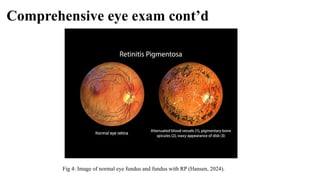

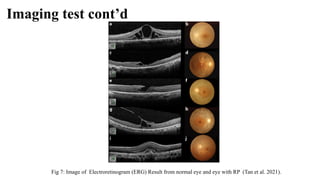

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a rare genetic eye disorder characterized by progressive degeneration of retinal photoreceptor cells, leading to vision loss, particularly starting with night blindness and resulting in tunnel vision. The condition is caused by mutations in at least 12 different genes and is diagnosed through comprehensive eye exams, visual field testing, electrophysiology tests, and imaging tests. While there is no cure, management options like vitamin A therapy and low vision rehabilitation can help improve quality of life, and emerging treatments such as genetic and stem cell therapies show potential for future advancements.