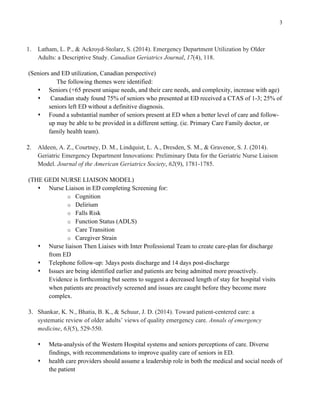

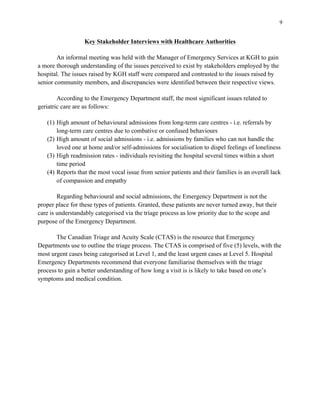

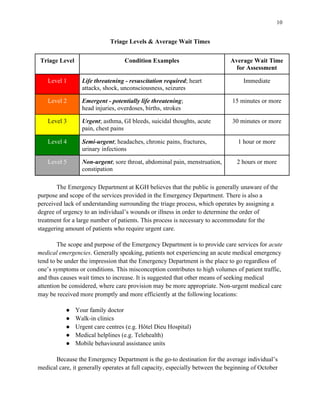

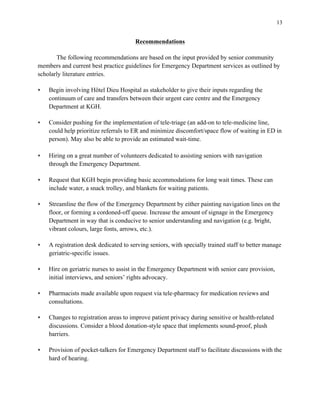

The document discusses barriers seniors face when navigating the emergency department at Kingston General Hospital and proposes two approaches to overcome these barriers: 1) Informing long-term changes to the physical and social environments of the emergency department based on best geriatric practices and senior experiences. 2) Educating and empowering seniors to better navigate the healthcare system and control their own health. It then reviews literature on improving emergency care for seniors, identifying themes such as the need for senior screening, dedicated staff like nurse liaisons, communication, discharge planning, and addressing seniors' unique needs.