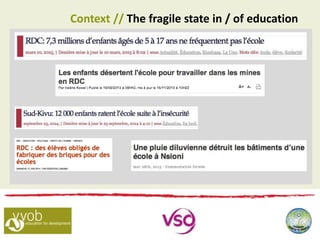

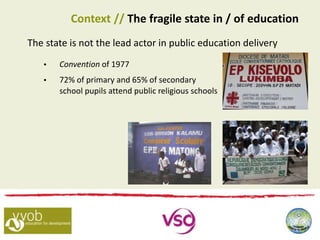

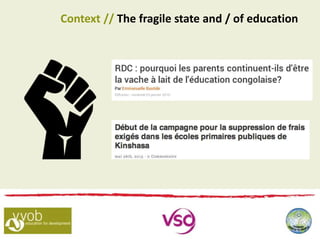

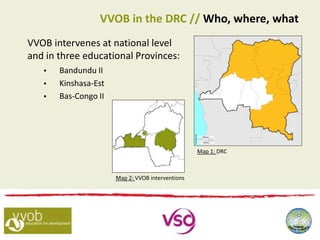

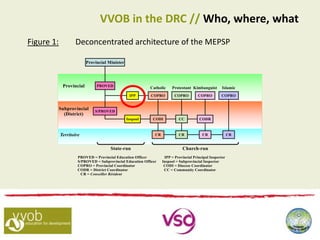

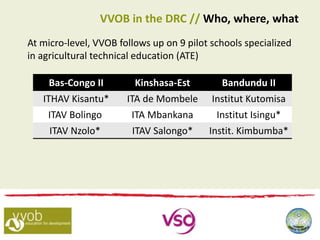

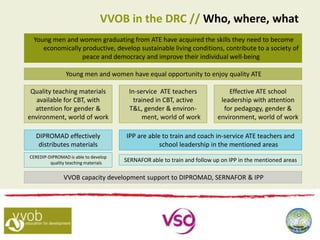

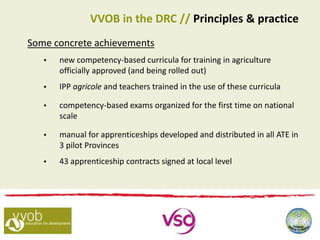

The document discusses the role of education as a tool for statebuilding in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), emphasizing the importance of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in fragile contexts. VVOB's interventions focus on improving agricultural technical education and facilitating better educational practices amidst a challenging state context. Key principles of VVOB's approach include building on existing frameworks, providing technical assistance, and fostering local dialogue to enhance educational outcomes in the DRC.