This document discusses the role of small scale enterprises in urban areas. It addresses how small businesses operate in cities, the challenges they face, and opportunities for supporting their growth. Key points include:

- Small businesses often operate out of homes or shared community spaces due to limited resources. This can cause environmental and safety issues if not properly regulated.

- Municipal governments need policies that facilitate rather than hinder small business, such as by providing affordable workspaces and transit options.

- Support programs can help small businesses through training, financing, networking and promoting innovation in environmentally-friendly practices.

- Integrating small enterprise activities with urban planning can benefit local economies while improving environmental standards and working conditions.

![sector of the urban economy. National governments and

donor agencies have recognized this fact by increasing

their support for small scale enterprise activity through

micro finance programmes and other innovative vehicles

such as incubator programmes.

In addition to creating employment, the SSE sector is

valued as a source of ingenuity and vitality, which in turn

influences urban communities beyond the realm of

economics. With the exception of housing, the ‘where’,

‘how’ and ‘why’ of SSE activity constitute the most

important factors in determining how urban space and

resources are used. It is therefore reasonable that the SSE

sector plays a greater role in new approaches to urban

planning.

In the area of environmental practices, many SSEs show

great resourcefulness in minimizing waste and in recycling.

Small operating budgets have made it necessary for

entrepreneurs to find ways to make ends meet, and this

invariably means making the best use of resources and

limited space. Moreover, most urban centres in the

developing world have active SSE sectors that provide

services in the areas of waste collection and recycling. In

some cities, the informal sector outperforms municipal

governments in waste collection. [Ali and Ali: 1993]

Yet, not all is environmental perfection with SSEs. In fact,

there are a vast array of environmental problems

associated with urban SSEs. There are far too many SSEs

in a variety of sectors — from tanning and electroplating

to artisanal activity — that can be the source of significant

negative environmental impacts on local communities.

The diversity, changing nature and growing number of

urban SSEs create an enormous array of environmental

challenges, both in terms of understanding and choosing

appropriate remedial methods.

Most often SSEs operate in surroundings characterized by

inadequate housing, transportation, water and sanitation

infrastructure, and health facilities. Cluttered streets, alleys,

commercial parks and inappropriate building space —

such as individual homes — often become makeshift

workplaces that can create unsafe conditions for workers,

family members and the broader community. It is within

the context of the precarious existence of SSEs that

solutions to environmental problems must be found.

Given the social and economic importance of SSEs, the

emphasis must be on introducing corrective measures to

reduce negative environmental impacts, and to ensure

that SSEs are at the centre of strategies which address

broader problems impacting on the urban environment.

Urban SSEs operate in an environment that can

experience rapid change through the adaptation of new

ideas and technologies. This dynamic provides a great

opportunity to create more sustainable patterns of

economic activity that can impact upon both the

entrepreneurial milieu and other aspects of urban life.

Finally, it is important to stress that making a stronger link

between the environment and SSE activity is not solely

about environmental standards. Efforts in this area should

be a part of a larger agenda to alleviate poverty, by

increasing and diversifying economic opportunities, and by

improving infrastructure, workplace and housing

standards. It is the intention of this document to

demonstrate how this is possible.

1.2 A Changing Development Context

and the Rational for this Document

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise is

designed to outline the conditions and factors that allow

small scale enterprise to play a larger role in improving the

living and environmental standards of cities. The

document highlights ideas, innovations and practices that

are realistic from a technical, economic, political and social

standpoint. A broad variety of options are presented on

how to incorporate small scale enterprise into schemes to

improve the physical environment of cities and eliminate

related conditions contributing to poverty. An important

theme of Reinventing the City is presenting solutions to the

environmental problems created by SSEs.

It would have been useful in developing this publication if

a vast array of information and project experience had

been available. This, however, was not the case.

Nevertheless, an extensive effort has been made to

collect and present as many key case studies as possible.

This document benefits greatly from the knowledge and

insight emanating from related spheres of activity, where

refinements and the emergence of new approaches are

creating new options for working with entrepreneurs,

workers, community groups and governments.

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-9-320.jpg)

![In the economic sphere, a great deal of knowledge and

experience has been accumulated in recent years on how

to assist SSEs. Micro finance, the practice of providing

small loans to individuals and community groups, has

opened up new possibilities for assisting the poor in

initiating and enhancing economic activities for their own

benefit. In addition, experiences with business incubator

programmes and related business services have shown

how cost effective instruments can be used to create new

enterprises, protect struggling ones, and introduce

technological change.

The renewed interest in participatory development, due

largely to the emergence of Participatory Rural Appraisal

(PRA), is setting new standards for development projects.

This emphasis on participation, combined with more

fundamental attempts to make governments more

democratic, accountable and responsive, has created the

possibility of tapping into previously under utilized sources

of collective and individual knowledge and skills.

Improvements in technology in a wide variety of areas,

such as renewable energy and the transportation sector,

are creating other possibilities. Yet the most important

development related to technology has been the shift in

thinking, from placing emphasis on the technology itself, to

understanding how technologies can be more successfully

integrated into the activities of family, community and the

workplace.

Although not traditionally focused on the SSE sector, the

field of occupational health and safety (OHS) offers great

insight on how changes can be made in the workplace to

improve safety standards and protect the environment,

while improving economic performance. Pilot activities,

undertaken by organizations such as the ILO, have

demonstrated an enormous potential to work with SSEs

to improve OHS standards.

Also, donor agencies such as CIDA are placing a greater

emphasis on developing practical tools and modifying

established practices for a more sustainable impact (e.g.,

environmental assessment to ensure that small scale

development activity is properly managed from an

environmental standpoint). The collective result of these

experiences is that much more is known about how to

work with individuals, communities, entrepreneurs and

local government to facilitate change.

1.3 Regarding the Content of this

Publication

It is important to underline a few key points concerning

this document. For reasons of expediency and focus,

Reinventing the City does not examine the role played by

SSEs in recycling and waste management. This subject is

relatively well documented and analyzed in a number of

publications [see Fernandez: 1997, Haan et al.: 1998 and

Furedy: 1990b]. Although much can be learned from the

experience of SSEs in this field, other topics and issues

need to be addressed to provide a more comprehensive

overview of the interrelationship between the urban

environment and SSEs, and the possibilities to promote

change. Nor will the use of command and control

legislation to police the activities of SSEs be explored.

Many would argue that the focus of this document should

be on the applicability of environmental measures,

regulations and controls. However, in the context of the

largely unregulated urban economic process in which SSEs

operate and flourish, it could be argued that the emphasis

should be on working with the possibilities provided by

this very situation. Despite a few notable exceptions, the

experience to date with regulation and enforcement of

SSEs has been overwhelmingly negative. Until local

governments are in a position to ensure adherence to

environmental standards in a judicious and effective

manner, the emphasis should be on working more

collaboratively, and finding other means to put pressure on

SSEs to adhere to better environmental practices.

1.4 Chapter Outline

In addition to introductory and concluding sections, this

document is organized into four main content chapters:

Chapter 2: Working in the City

To better understand the SSE sector, this chapter presents

information on statistics and trends regarding the place of

SSEs in the urban economy. The SSE sector is examined

in relation to housing and transportation practices and

standards, trends, spatial arrangements, and local

government resources and capacity. The chapter

concludes with an examination of the environmental

impact of SSEs in terms of resource utilization, and the

sector's contribution to pollution, overcrowding and the

faltering infrastructure of cities.

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-10-320.jpg)

![2.0 Introduction

The very apparent pollution, squalidness, poverty and

breakdown of services found in cities in developing

countries can easily shape negative sentiments about what

it must mean to live and work in such conditions. Cities

in developing countries can be awful places because of

these problems, but this does not tell the whole story.

They are also highly animated, full of life and vigour. Much

of the credit for this goes to the SSEs filling the streets,

alleys, markets, parks and buildings. A late evening traveller

to Dhaka, Lahore, or other South Asian cities, is struck by

the noise and vivacity of the commercial activity

emanating from the streets and other SSE workplaces.

On market day in countless African cities, the limits of the

transportation system and infrastructure are quickly

tested as the volume of commerce swells.

The resonating character of these cities is not the creation

of city managers and planners. As will be demonstrated

in this chapter, established planning grids and

neighbourhood designs have largely been ignored by

people to permit a more interactive and practical

relationship between the home, common space and

entrepreneurial pursuits. As such, SSEs tell us a great deal

about how urban centres could be designed differently.

Clearly, small scale entrepreneurial activity is not the only

factor that comes to define what cities are, but for a large

percentage of the urban population it is a major element.

This chapter attempts to provide insight into the

environmental, cultural, social, political and economic

dynamics shaping the character and extent of small

enterprise in cities. To help set the stage, the chapter

begins with a brief examination of some findings and

reflections related to the economic importance of urban

SSEs.

2.1 The ‘Survival Economics’ of Urban

SSEs

Below are a series of summary statistics and observations

regarding urban SSEs. They provide an interesting, if

occasionally contradictory, portrayal of the sector. Certain

of the points raised here will be elaborated upon in

subsequent sections of this document:

• Most enterprises categorized as urban SSEs are very

small. In a study of African SSEs, the majority were

classified as one-person operations. [Mead and

Liedholm: 1998, 62] Yet some SSEs can employ large

numbers of workers. Informal waste collection and

recycling operations are good examples of this.

• A large percentage of SSEs are home based

enterprises.

• The percentage of the urban population finding work

in the SSE sector is growing. The Asian Development

Bank (ADB) reports that three-quarters of all new

jobs in South Asian mega-cites are created by the

informal sector. [ADB: 1999, 38] A World Health

Organization (WHO) study found that 45%–95% of

the workforce in developing countries can be found

in small factories and related industries. [reported in

McCann: 1996]

• Although the majority of urban SSEs are engaged in

non-productive activity, there is a significant minority

involved in productive activity best described as

industrial.

• "In most countries the majority of (SSEs) are owned

and operated by women. Furthermore, since working

proprietors are the single largest category of the

labour force, the majority of workers are women."

[Mead and Liedholm: 1998, 64]

• Studies indicate substantial differences in economic

efficiency by enterprise size. In particular, the "returns

per hour of labour are significantly higher for

enterprises with 2-5 workers, compared to those

with one person working alone. This increase in

economic efficiency continues for the next higher size

group, those with 6-9 workers; thereafter, the results

are more ambiguous."

[Mead and Liedholm: 1998, 64]

• "(SSEs) are in a constant state of flux. During any

given period, new firms are being created (new starts,

or enterprise births) while others are closing; at the

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

5

Chapter Two Working in the City](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-12-320.jpg)

![same time, some existing firms are expanding and

others are contracting in size. Since these individual

components of change can move in opposite

directions, figures on net change mask the magnitude

of the churning that takes place."

[Mead and Liedholm: 1998, 64]

• The overall contribution of SSEs to Lao's Gross

National Product (GNP) is between 6-9%. [Daniels:

1999, 55] In a nationwide survey of Kenya, urban

SSEs were found to provide 50% of family income;

18% of SSEs provided all the household income.

[Daniels: 1999, 59] "One-third of all working persons

are employed in SSEs and the sector contributes 13%

to Kenya's Gross Domestic Product." [Daniels: 1999,

63] In Guatemala, it is estimated that the urban

informal economy accounts for 34% of the country's

GNP. In 1960, the informal sector accounted for only

5% of Guatemala's GNP.

[Villelabeitia: 2000]

• A study of informal enterprises in Nigeria

demonstrated that informal enterprises rarely have

written down conditions of work or fixed working

hours. [Faphounda: 1985, 79] Informal enterprises

have variable hours of operation, usually running for

about 11.5 hours every day. Only 4.4% of the

enterprises operated for exactly eight hours a day,

and about 7% operated for less than eight hours.

Even though the enterprises had long operating

hours, they usually worked for one stretch at a time,

rather than in shifts.

[Faphounda: 1985, 81]

• Most SSEs operate at low, often obsolete levels of

technology. However, even in the most advantaged

enterprises, progress can be made in technological

capacity.

[see King: 1996 and McCormick: 1998]

• In India, SSEs "produce crude, low price final products,

which are sold to consumers either directly or

through distribution channels. These firms are

sometimes found to compete with larger firms that

exist in the same industry segment, but which

produce differentiated products, that incorporate

special design features that make it stand out."

[Vachini: 1991, 26]

• Clustering, whereby a large number of enterprises

from the same or related sectors locate in the same

area, is an important phenomenon of the SSE sector.

Clustering occurs for a number of economic reasons

to allow SSEs to achieve economies of scale,and share

technology and labour. Clustering can take many

different forms. Clustering in Asia and Latin America

can be more sophisticated than that typically found in

Africa. [McCormick: 1998] For example, clusters in

Latin America and Asia have been known to become

important centres in the manufacturing of a wide

variety of goods (i.e., from footwear to medical

inputs). [McCormick: 1998, 11] While in Africa,

clusters can consist of thousands of micro enterprises

operating at a very basic technological level.

[McCormick: 1998, 11]

• There can be considerable economic interaction

between SSEs and medium and large scale

enterprises — e.g., SSEs are often relied on to

provide small implements in the production of larger

goods.

• Cultural, social and family considerations can be as

important as economic factors in determining the

location, size and number of SSEs working on or in a

particular street or dwelling. Co-operation and

mutual support can be found within enterprises that

normally one would perceive to be in competition

with one another.

[see Gough: 2000 and Benjamin: 1991]

The contribution of SSEs to the urban economy is

significant and growing. Although statistics vary, the

tendency is towards estimating a high percentage of the

population finding work in SSEs — somewhere between

one-half to three-quarters of the urban workforce. The

major problem in undertaking statistical work on SSEs is

studying enterprises that mostly operate in a clandestine

manner outside the formal economy.

Yet, the most important point to retain regarding urban

SSEs is their role in combating poverty. By supplementing

incomes and creating singular employment opportunities,

SSEs are in many ways a last line of defence against certain

poverty, especially for women. The availability of flexible

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-13-320.jpg)

![SSE opportunities is of tantamount importance for

women who must also contend with demanding domestic

responsibilities that tend to limit economic options.

2.2 The Home as a Workplace

Home based enterprises (HBEs) are the best example of

the economic convenience afforded by the SSE sector.

The concept of combining living and working space has

been around a long time, including in Europe where it was

very common up until the Renaissance period. This

arrangement served more than economic purposes,

contributing greatly to medieval society by making the

"medieval family a very open unit." [Schoenauer: 1992,

228] Lewis Mumford, one of the earliest critics of modern

urban life, described the European medieval home as

follows:

The medieval family included, as part of the normal

household, not only relatives by blood but a group of

industrial workers as well as domestics whose

relation was that of secondary members of the

family. This held for all classes ... for young men from

the upper classes who got their knowledge of the

world by serving as waiting men in a noble family;

what they observed and overheard at meal-time

was part of their education. Apprentices, and

sometimes journeymen, lived as members of the

master craftsman's family. If marriage was perhaps

deferred longer for men than today, the advantages

of home life were not entirely lacking even for the

bachelor.

[Mumford: 1961, 281]

The separation of the household from the workplace had

a profound and lasting impact on the future evolution of

cities in European countries. In developing countries, the

practice of integrating home and entrepreneurial pursuits

has been kept alive for both economic and social reasons.

It particularly thrives in places where strict rules about

land use are not enforced.

[Medina: 1997]

The home doubling as a workplace reduces costs. It

affords parents, mostly mothers, the opportunity to stay

close to and care for their children. Gough notes that "in

almost all low income settlements in (developing)

countries, people in HBEs can be seen cooking, sewing,

selling drinks and food, keeping animals, mending and

making shoes, manufacturing various goods, cutting hair,

giving injections, and renting rooms." [Gough: 1996, 95] In

the rapidly growing low income settlement of Madina

Ghana, located on the outskirts of Accra, two-thirds of all

dwellings have at least one HBE. [Gough: 2000] A study

of informal settlements in Port- au-Prince, Haiti,

determined that home based entrepreneurship was so

far-reaching that housing units were treated as places of

production. [Fass: 1977 quoted in Tripple: 1993] In

developing countries, HBEs can be found in middle-class

dwellings, especially in countries experiencing an

economic downturn.

[Olufemi: 2000]

A study of HBEs in a‘Bustee’ (Bengali for slum) community

in Calcutta describes the character of HBEs and how they

come to influence a neighbourhood's character:

• In the bustee, almost all of the homes located near

the main or secondary roads have some kind of small

business activity within their domestic space.

• Some households with interior locations are involved

in (productive) oriented activities like raakhi making,

bidi making, tailoring, agrabatti rolling, etc.. These

activities do not require formal shops for their

distribution.

• A number of shops (home based) selling the same

product can be sustained by high demand. Only

special services shops, such as metal repairs, can be

located away from main roads.

• Given the use of domestic space for HBE activity,

common spaces are shared by families for cooking,

washing and drying clothes, relaxing, playing and

sometimes eating. Thus a very close interrelationship

develops between houses and their spatial

surroundings. Spaces for domestic and income

generating activities exist and interact to the mutual

benefit of the bustee dwellers.

• Bustee dwellers sacrifice ‘living’ quality to a great

extent to accommodate their income earning activity,

since this is important to their survival. Prime space

is given over for income generation. The lack of

proper space forces them to adjust to the existing

conditions as best as possible, often involving

sacrifices in other daily living activities.

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-14-320.jpg)

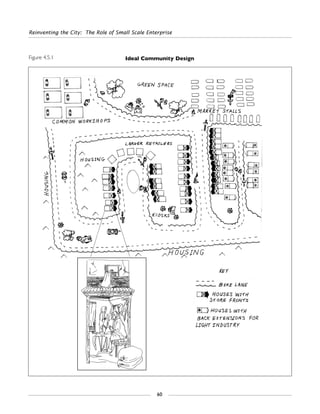

![[Ghosh: 1994, 77-79]

Similar to Ghosh's findings, a study in Aba, Nigeria,

determined that "usable space takes precedent over

aesthetics and permanence, and both housing and

environmental quality in terms of construction standards

are of little significance, compared with employment."

[Nwankama: 1993] The drawing in Figure 2.2.1 is an

overview of the Gorcha bustee community in Calcutta,

India, which is the focus of Ghosh's study. Figures 2.2.2

and 2.2.3 are ‘section through’ drawings of two home

based entrepreneurs in Gorcha that established

enterprises in extensions of their homes.

Box 2.1 is an extract from a study of HBEs of a very

different kind, found in the Viswas Nager settlement of

East Delhi. Benjamin uses the term ‘neighbourhood-as-

factory’ to describe the entrepreneurial activity of HBEs

there. [Benjamin: 1991] The experience of Viswas Nager

is significant because it broadens significantly the

perception of what constitutes HBEs, and the role they

can play in building communities. InViswar Nager, a strong,

well organized SSE sector, led by HBEs, worked with local

officials to improve conditions in terms of infrastructure

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

8

Box 2.1 The Home Based Factories of East Delhi

In the East Delhi colony ofViswas Nager, the outward image is of a typical Delhi settlement in various stages of construction —

endlessly reproducing themselves through additions or subdivisions, and hectic movement of people and vehicles along the inner

streets. But these impressions are misleading. Inside the ‘houses’, generally in basements and on ground floors, are factories

reminiscent of the Industrial Revolution. Machines whir in the dim and often dusty light, their operators supervised carefully by

foremen.The cycle rickshaws that must be dodged in the streets are not only transporting people, but also raw copper stock

and semi-finished copper wire among hundreds of small (home based) factories.

The production system of Viswas Nager has developed into a neighbourhood-as-factory — a network of small firms located in

the same area, which both compete and co-operate with each other. There is the pervasive smell of new brickwork and the

noise of machinery in front room shops. Their productivity stimulates the markets and creates job, which leads to even greater

production levels and continues a cycle of successful economic growth.

To observers, its seems impossible that sophisticated manufacturing takes place in such a rudimentary environment. As of 1991,

up to 80% of the city's manufacturing was taking place in such neighbourhood factories. Industries support each other in East

Delhi. Copper wire and cable manufacturing industries depend on secondary manufacturing such as plastic recycling and cycle

rickshaw fabrication.

Although all modes of transportation are used, the cycle-rickshaw is the key. Typically, cycle-rickshaws are hailed from the street

as needed, but some entrepreneurs maintain their own fleet. The differentiated transport system is well suited to the diverse

conditions of the roads within the settlement. While heavy vehicles are efficient for transporting goods on high quality roads,

only cycle-rickshaws and animal driven carts are capable of traversing the narrow, unpaved and flood prone roads located in

sections of the settlement.

By 1991, the colony had a workforce, political strength, a diversified property market and a number of local money lending

associations. Viswas Nager is an example of difficult but successful co-operation between common people and institutions. The

efficiency of the colony's development by increments is a lesson for those who believe that massive public or private

interventions in land and industrial development are necessary for economic progress.

[Benjamin: 1991,4-100]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-15-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

9

Figures 2.2.1. 2.2.2, 2.2.3

Overview of

Gorcha Bustee

in Calcutta

India

[Ghosh, 94]

Section through of two home-based enterprises in Gorcha Bustee [Ghosh, 94]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-16-320.jpg)

![and sanitation.

2.3 Community Space as a Workplace

The first layer of outdoor SSEs are HBEs adjacent to

homes such as in figure 2.3.1 and 2.3.2. Nwankama notes

that in communities such as Aba, Nigeria, where HBEs

flourish, the physical distinction between the interior and

exterior of the home is artificial, influenced primarily by

"climate, the scale and organization of the outdoor space,

and the nature of work and size of the enterprise."

[Nwankama: 1993, 128]

HBEs attached to and surrounding dwellings are part of a

larger network of SSEs, operating in a diverse range of

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

10

Figure 2.2.4

Section through of another home-based enterprise and location in Gorcha Bustee. [Ghosh, 94]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-17-320.jpg)

![outdoor locations and conditions. Some outdoor SSEs

operate with permits from established buildings and

locations in the same way small enterprises operate in

Canada.Yet most do not. Although mostly service oriented,

there can be very large, outdoor SSEs involved in heavy

industrial activity. [Pallen: 1997b] Depending on the degree

of by-law enforcement,any open or free space is a potential

workplace — i.e., alleys, streets, sidewalks, railway lines,

parks, intersections, markets, industrial parks and rooftops.

A study by McGill University’s Centre for Minimum Cost

Housing (CMCH) of two slums in Indore, India,

documented the diverse and complex variations of spatial

requirements needed by an equally diverse assortment of

outdoor work activities: "They varied from as small as 2

square metres, in the case of paper bracelets, to as much

as 36 square metres for the repair and refurbishment of

wooden crates. Some of the activities needed shelter,

others did not. Most required not only a work space, but

also a space for storing either raw materials or finished

products, or both."

[Rybczynski et al.: 1984, 21]

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

11

Figure 2.3.1

In Aba Nigeria, carpenter and

his apprentice use space at side

of house as a work space. The

workplace is highly visible to

passerbys. [Nwankama, 1993]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-18-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

12

Figure 2.3.2

A beedi seller (Indian cigarette) sets up a stall along side a house in Gorcha Bustee

in Calcutta, India. [Ghosh, 94]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-19-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

13

Figure 2.3.3

In Aba Nigeria, an overhead view

of two small shops, a breakfast

joint and used clothes store

alongside a work place. The work

place is used for bicycle repairs.

[Nwankama, 93]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-20-320.jpg)

![There is also the phenomena of mobility: "There are

mobile shops — carts and moveable kiosks — that are

operated by hawkers and peddlers. The distinction

between mobile and fixed shops can be blurred, since

frequently the first stage of establishing a permanent shop

is simply to park a pushcart in one location, and eventually

to upgrade it into a semi-permanent structure."

[Rybczynski et al.: 1984, 33]

Figures 2.3.3, 2.3.4, 2.3.5 and 2.3.6 are drawings from Aba,

Nigeria, demonstrating the variety of uses and shapes of

outdoor SSE space in that city.

To the outsider, the locations occupied by outdoor SSEs

can appear overcrowded and chaotic. The impression is

that nothing has been planned. However, this is most

often far from the truth. In fact, there is usually an innate

logic behind where and how enterprises are located. Post

describes the situation of SSEs operating in the town

centre of Kassala, Sudan, as follows:

An intricate network of interdependency relations has

developed, requiring that members of the same

professional group work at the same place (for

example, butchers, leather manufacturers, gold and

silversmiths, etc.). Tailors use the arcades in front of

fabric shops; retail grain sellers working the street are

near to their wholesale colleagues (where supply trucks

unload); soft drink and fruit juice sellers occupy sites

near the bus terminal; and craftsman are ideally situated

for direct contact with the consumer ... Street traders in

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

14

Figure 2.3.4

Space between a road and railroad is used for block-making in Aba Nigeria.

[Nwankama, 93]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-21-320.jpg)

![particular rely on large streams of passers-by and

depend on small and frequent orders with suppliers. The

importance of mutual proximity has even increased over

the last few years due to the chronic shortage of all sorts

of commodities, making personal contacts and swift

communication vital in order to secure essential supplies.

[Post: 1996, 37]

The type of entrepreneurial networks and clusters

described by Post can be found in various shapes

throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America. From

neighbourhood to neighbourhood and street to street,

SSEs respond to the needs of local residents. At the same

time, cultural and family traditions can also intertwine with

economic factors to influence the shape and character of

streets and neighbourhoods [see Bishop and Kellet: 2000].

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

15

Figure 2.3.5

A wider street in Aba Nigeria is used for metal work and for auto repairs. [Nwankama, 93]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-22-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

16

Figure 2.3.6

Small shops are built behind the railroad at a street intersection where tires, candies, gin and soft

drinks are sold. Places are also available for hair braiding and a food vendor. [Nwankama, 93]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-23-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

17

It is also not uncommon to find a number of women

selling the same goods and services in streets, shops or

homes, in close proximity to one another. This type of

pattern may have more to do with mutual co-operation

and self-support, as opposed to the, by and large,

economic motivation behind clustering. Moreover, with

the absence of such public buildings as community

centres, and in some cases schools and religious buildings,

the premises of SSEs such as tea houses can serve a social

function, by providing people with public meeting spaces.

[Rybczynski et al.: 1984, 33]

Figure 2.3.7

Scene of the daily market in the main passageway of the Gorcha Bustee in Calcutta, India. [Ghosh, 94]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-24-320.jpg)

![The patterns and arrangements of outdoor SSEs have

developed slowly over time and Post appeals to urban

planners to be more appreciative of these ‘self chosen

locations’: "Although chosen under sometimes severe

economic, cultural and physical constraints, they

nevertheless demonstrate the rational of differing

settlement choices. Knowledge of the spatial logic of

survival is essential to the formulation and implementation

of any proactive planning on behalf of small enterprises."

[Post: 1996, 39]

2.4 Transportation and Urban SSEs

Although most entrepreneurs in the SSE sector would

prefer to own a motorized vehicle, the reality is that very

few do, or ever will. A variety of transportation modes are

available to SSEs, yet most rely on non-motorized vehicles

(NMVs). NMVs, such as those found in Figures 2.4.1 and

2.4.2, play an important part in the economic world of

SSEs and, indeed, in the overall economies of developing

countries. In Viswas Nager [see Box 2:1], a survey of

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

18

Figure 2.4.1

NMVs in Asia.

[World Bank, 1995, 9]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-25-320.jpg)

![entrepreneurs revealed that a major reason for their

economic success was the availability and suitability of low

cost cycle-rickshaw transportation.

[Benjamin: 1991, 41]

As the World Bank points out, NMVs such as bicycles,

cycle-rickshaws, animal carts, push and pull carts, are "non

polluting, low cost mobility powered by renewable energy

sources that are well suited for short trips in most cities."

[World Bank: 1995, xii] In some cities and communities,

NMVs can provide the most mobility. In Yogyakarta,

Indonesia, almost 10% of the population live along the

Code River, where access between houses or access

outside the settlement to surrounding communities is

possible only by internal footpaths and narrow streets. In

other words, there is no access into and throughYogyakrta

by car.

[Nareswari: 2000, 3]

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

19

Figure 2.4.2

NMVs in Asia.

[World Bank, 1995, 8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-26-320.jpg)

![SSEs, like all enterprises, rely on existing transportation

systems to move goods, provide services, and facilitate

other economic activity. Yet today, neglected trans-

portation networks are being refitted to facilitate the

movement of commuters in automobiles, thereby adding

to the problems of congestion and pollution. At the same

time, more realistic and pragmatic approaches to urban

transportation, which consider the needs of all users, are

ignored.

[see UNDP: 1992]

The World Bank [1995, 1] undertook a study of ten major

Asian cities and identified the following trends that impact

negatively on the use of NMVs:

1. Increased motorization (including the increased use

of motorcycles) and a consequent reduction in the

street space available for safe NMV use.

2. Exclusion of NMV needs in urban transport

planning and investment programmes, resulting in

inadequate facilities for NMVs.

3. General trend toward modernization of Asia cities,

which promotes attitudes that NMVs are backward.

4. Tendency to believe that NMVs are the cause of

urban traffic congestion.

5. Increased trip lengths caused by changes in

metropolitan spatial structure.

The World Bank adds:

In many Asian cities there is an apparent bias against

NMVs. Hanoi, Dhaka and Metro Manila are a few

of the cities that have as official policy the reduction

or elimination of NMVs because of perceived impact

on congestion and safety, as well as the ‘degrading

nature of the work required of the operator’ ... the

consequence of anti-NMV biases is unbalanced

transport planning, which results in accommodating

the needs of motorists at the expense of NMV

operators and users. Such unbalanced planning can

actually lead to a deterioration of traffic conditions for

both motorized vehicles and NMVs.

[World Bank: 1995, 59-60]

In Jakarta during the 1980s, roughly 20,000 cycle-rickshaws

were tossed into Jakarta Bay and another 30,000

confiscated by city officials in a effort to eliminate

‘backward technology’. [Gardner: 1998, 16] In some

countries, such as Vietnam, municipal policies have actually

contributed to a reduction in bicycle use. [Gardner: 1998,

16] Recently, the municipality of Rawalpindi, one of

Pakistan's largest cities, banned NMVs in the old town

centre, where the streets are narrow and well suited to

such vehicles.

Such attempts to reduce NMV use seem more

preposterous when one considers that the overall use of

NMVs in Asia is actually growing. [World Bank: 1995]

Not only are NMVs more economical, they are also more

practical in most circumstances. Bicycles trips, for

example, compare favourably with cars for urban trips of

about 2 kilometres. "In Beijing, bicycles are faster than the

bus or subway for trips up to 6 kilometres and remain

competitive with public transportation for journeys of up

to 10 kilometres." [Gardner: 1998, 18] Subsequent

chapters will discuss the efforts of certain municipalities to

capitalize on these inherent advantages to improve and

increase the use of NMVs.

Another aspect of NMVs that is not well known is the

significant amount of small scale entrepreneurial activity

that exists in support of NMVs. NMVs are "labour

intensive modes of transport that rely extensively on the

use of local technologies and skills." [World Bank: 1995,

xii] The World Bank describes the importance of the

NMV sector in Asia urban economies, as follows:

The cycle-rickshaw industry in Dhaka — including

drivers, repair persons, owners, mechanics in assembly

shops, and retailers in components shops — directly

provide 23 percent of the city's employment.

Similarly, approximately 20 percent of the jobs in

Kanpur, India are in the NMV sector, which includes

all employment related to bicycles, rickshaws, animal

carts and handcrafts. To the extent that motorize

vehicles replace NMVs in these cities local economies

will drastically change with consequent dislocation

effects. Nevertheless, the inventory of Asian cities

conducted for this recent study found that local

governments often underestimate the economic

impact of the NMV sector.

[World Bank: 1995, 57]

NMVs would seem to be as natural an ally as local

planners could hope to have in creating employment for

vulnerable groups, providing affordable and accessible

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-27-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

21

... Auto rickshaws number over 3 million, and are

among the largest contributors to poor quality urban

air. They provide passenger as well as goods

transportation and account for a large percentage of

the traffic on roadways. Many of these vehicles are

up to 30 years old and still use leaded gasoline due

to the absence of strict emission regulations and the

owners limited finances. The majority of the vehicles

are poorly maintained and do not employ exhaust

treatment devises. Also, used oils are often added to

agricultural producers while urban dwellers are thought to

engage in industry and services is increasingly misleading."

[Tacoli: 1998a, 3] She goes on to add:

The growing evidence of the scale of and nature of

urban agriculture and of rural non agricultural

enterprises and employment suggests that these

distinctions are over simplified descriptions of both

rural and urban livelihoods. The urbanization of rural

economies and employment structures is also often

transportation, and in reducing pollution and the

overcrowding of cities. The relatively soft clanking of

bicycles, trailers and carts would seem to be a perfect

antidote to overheated and noisy cities.

Two stroke engine auto-rickshaws, scooters and motor

cycles are also very popular in Asia, and probably create a

considerable amount of employment in the SSE sector

through repairs and other services. Yet unlike NMVs, auto-

rickshaws and other small scale motorized vehicles are

notorious polluters. The EnvironmentalTechnology Centre

of Environment Canada describes the state of auto-

rickshaws in Asia as follows:

the gasoline at higher than the manufacturers’

recommendation. The result is higher exhaust

emission rates.

[Environment Canada: 1997, 3]

2.5 The Blurring Distinction Between

Urban and Rural Entrepreneurship

Small scale entrepreneurial activity is a key dynamic in one

of the most significant changes taking place in developing

countries — the eroding distinction between urban and

rural life. AsTacoli points out, the assumption of a sectoral

divide, whereby "rural populations are seen primarily as

The Ferozepur Road in Pakistan. Redefining rural work.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-28-320.jpg)

![most evident in the areas immediately around or well

connected to the urban areas.

[Tacoli: 1998a, 3]

This new reality is best observed in the growing peri-

urban zones surrounding urban centres. In city outskirts,

there can exist a conglomeration of entrepreneurial

activity encompassing industry, agriculture and service

activity. Increasingly, rural and peri-urban entrepreneurs

are operating closer to urban centres to have better

access to clients and reduce transportation costs.

[Werna: 1997, 392] In Pakistan, the 50 kilometre long

Ferozepur Road that joins Pakistan's second largest city

Lahore with the ancient city of Kashur is a case in point.

From Lahore, on both sides of the Ferozepur Road,

entrepreneurial activity dominated by the SSE sector

stretches for well over 15 kilometres. Agricultural activity

is still very apparent from the road. [Pallen: 1999] It is not

unthinkable that one day entrepreneurial activity along the

Ferozepur Road will extend from Lahore to Kasur.

In rural Bangladesh, agricultural revenue remains the main

source of income. However, the percentage coming from

non-farming activity is increasing dramatically. It has been

estimated that by 2005, over 62% of the rural population

of Bangladesh will find work in non-farming activities.

[World Bank: 1997, 18] Moreover, increasingly the ranks

of the peri-urban work force is made up of rural workers

commuting to peri-urban areas on a daily basis. [World

Bank: 1997, 18] In strictly rural areas, there are significant

changes taking place in local economies:

Manufacturing in permanent establishments

(manufacturing outside the household, often with the

help of hired workers), excluding handlooms, is

dominated by traditional food processing, textiles and

basic metals, accounting for 85 percent of

employment and 78 percent of value added ... The

sector has, nonetheless diversified considerably over

the 1980s. The list of the top 15 industries by

employment has changed considerably towards a

clear urban and peri-urban tilt, both with regard to

market orientation as well as enterprise location, and

non traditional small industries have experienced

rapid growth.

[World Bank: 1997, 56]

Similarly in cities, the practice of urban agriculture, defined

as "the production of food and non-food through

cultivation of plants, tree crops, aquaculture, and animal

husbandry, within urban and peri-urban areas", is on the

rise. [Lindayati: 1996, 3] Urban agriculture is undertaken

to generate income and food for personal consumption.

Backyards, front yards, planters, rooftops, abandoned

buildings, community lands, roadsides and other open

spaces are all potential spots for urban agriculture. In the

1980s, 60% of Greater Bangkok was used for urban

agriculture. [Mougeot: 1993] As a general rule, urban

agriculture finds creative uses for unserviceable pieces of

land, space and water. [Mougeot: 1993] Urban agriculture

is drawing the attention of international organizations,

such as the International Development Research Centre

(IDRC) of Canada, who are trying to promote and

improve upon present urban agricultural practices.

Eventually, changing urban and rural circumstances are

going to force development practitioners to rethink long-

standing approaches to development and, in particular, the

centre piece of development activity, employment

creation. New ways will have to be found to better

integrate industrial and agricultural activity.

2.6 The SSE Sector and Housing

Standards

A housing crisis exists in cities throughout the developing

world, in terms of both availability and quality, and

attempts to provide basic shelter for the poor have

produced mixed results. One problem identified by

McGill University’s CMCH, relating to SSEs, is that

planners and government officials have never understood

that there is "nothing basic about basic housing."

[Rybczynski et al.: 1984, 1] In the past, the decision making

process in housing construction has been too heavily in

favour of finding economic efficiencies in the site layout

through optimizing plot ratios and widths and

construction material.

This approach leaves little room to consider issues of

culture, family complexities and home based

entrepreneurship. The solution, according to the CMCH,

is a new set of settlement standards. "These standards

should seek to accommodate, rather than to reorganize.

They should reflect the (sometimes harsh) reality of the

urban poor, and they should respond to their special

needs, not to an idealized set of criteria."

[Rybczynski et al.: 1984, 1]

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-29-320.jpg)

![The system of housing championed by the CMCH is

based on housing patterns found in informal settlements,

where houses are routinely built or reconfigured

according to family size, cultural values and the need to

accommodate home based work. As Rybcznski points

out, rather than viewing informal settlements as a

problem, more attention must be payed to understanding

their good qualities in terms of how they respond to the

needs of people:

Informal Housing .... represents a solution rather than

a problem. It is moreover, a solution that appears to

deny conventional planning orthodoxy. The priorities of

the slum dweller are frequently not those of the

municipal authorities. Space takes precedence over

permanence. A porch may be built before a bathroom;

a workplace may be more important than a private

bedroom. The apparent inversion of values is especially

evident in the public spaces. Whereas planned sites

and services projects usually incorporate rudimentary,

minimal circulation spaces, the public areas or slums

are characterized by richness and diversity.

[Rybcznski et al.: 1984, 1]

Similar to the small enterprise sector that supports NMVs,

networks of informal builders and renovators serve the

informal housing market. Informal builders are highly

responsive to the building needs of the poor, and as a

result represent a very large share of the new housing

built in developing countries in terms of numbers and

value. [ILO: 1995] Although SSE services in the housing

sector may be more responsive, it is not clear what quality

of services are being provided. Carr-Harris, for example,

believes there are major issues that need to be addressed

in terms of health and safety standards, especially related

to building materials:

As poor people generally build their own homes without

any government subsidies, they are (often) forced to

use expensive and hazardous materials. During visits

to four or five squatter areas in Delhi, it was noted that

asbestos was a material commonly used for roofing,

when it is known to have a carcinogenic effect. Several

homes have brick walls with black polythene that is

believed to be associated with the high incidence of

coughs, colds, pneumonia and tuberculosis as polythene

forms are inadequate cover against the cold and damp.

Yet other homes had tin roofs which are inappropriate

for indoor cooking. These findings have been

corroborated by other studies of Delhi's urban poor.

[Carr-Harris: 30]

2.7 Local Government

This report cites a number of examples of national and

local governments attempting to understand and improve

the circumstances under which SSEs operate. However,

normally the relationship between SSEs and government

authorities is not healthy. SSEs face the same challenges as

everyone in terms of local governments not delivering

badly needed services. As a result, there is a general

indifference towards governments and what they have to

offer, which manifests itself in a number of ways. In

Pakistan, for example, government officials claim that in a

country of 150 million people, only 1.2 million pay taxes.

[Bearak: 2000]

Also, SSEs must often operate under inappropriate

regulations and by-laws that are administered and

enforced in an uneven manner. Local authorities, who are

unsure of how to deal with what appears to be chaos,

disorder and defiance by SSEs, can end up taking steps that

lead to unfortunate events, such as what occurred in

Mexico City in 1995. In that case, police and hundreds of

informal street vendors clashed violently after a legal

order was issued banning the vendors from the city

centre. The conflict arose, despite years of research and

discussion, between the vendors and authorities regarding

alternative arrangements. [Harrison and Mcvey: 1997]

This type of incident has been re-enacted in countless

other locations in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-30-320.jpg)

![SSEs are reluctant to pay taxes because local governments

do not provide SSEs with infrastructure or services.

Moreover, rarely will small scale entrepreneurs take the

time to register their enterprises. But even if an

entrepreneur wanted to be formally recognized, there is

usually little to be gained, except possibly a lot of red tape.

Box 2.2 summarizes the famous study by Hernando de

Soto on the obstacles faced by informal enterprises

wanting to be legally registered as a small industry.

2.8 Environmental Impacts of SSEs

There is no denying that unwanted environmental impacts

are occurring as a result of urban SSE activity. In some

cases, the consequences can be quite significant in local

communities. The main negative environmental impacts of

urban SSEs are seen as follows:

1. Contribution to the congestion and overcrowding of

cities. The manner in which SSEs occupy public

spaces can be disruptive. Similarly, with shelter

functioning as much as production units as homes,

there are conflicts and undesirable compromises

about how space is used.

2. Poor occupational health and safety (OHS) standards

put the health and safety of workers, entrepreneurs,

family members and the community at risk.

3. The inefficient use of resources, resulting in pollution

and the absence of pollution mitigating technologies.

4. Indiscriminate use of hazardous substances, such as

chemicals, dyes and disinfectants, in a wide range of

unregulated industries.

5. A wide variety of SSE activities for which little is

understood about their environmental impacts.

6. In peri-urban areas, expanding small scale industrial

activity is absorbing farmland. Activities such as

brickmaking and small scale mining are playing havoc

with local ecosystems.

SSEs may not be large in size but they are numerous, and

given they often locate close to or within communities,

there is great potential to do harm, especially to the poor:

Pollution affects the poor more than the better off as

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

24

Box 2.2 The Challenge in Becoming Legitimate

The Instituto Libertad y Democracia (ILD) undertook a simulation to measure the costs of access to industry. To do this, ILD

rented the premises of an established factory, installed sewing machines, knitting machines and other implements, and recruited

four university students to undertake the various bureaucratic procedures, under supervision of a lawyer experienced in

administrative law.

In addition to being very widespread in Peru and thus culturally significant, the activity chosen for the simulation was highly

representative of the obstacles faced by small scale entrepreneurs. It required approximately 60% of the bureaucratic

procedures common to all individual activities, and 90% of those required of non-incorporated individuals. The team also

decided to handle all the necessary red tape without go-betweens — as a person of humble origins would do — and to pay

bribes only when, despite fulfilling all the necessary legal requirements, it was the only way to complete the procedure and

continue with the experiment.

The results showed that a person of modest means must spend 289 days on bureaucratic procedures to fulfill the 11

requirements for setting up a small industry. The cost to establish a formal small industry represented the cost of 32 times the

monthly minimum wage at the time.

[De Soto: 1989]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-31-320.jpg)

![most (SSEs) (polluting or otherwise) are located in low

income areas ... high levels of air pollution associated

with small acid and chemical processing units in North-

east Calcutta were largely ignored by the government of

West Bengal despite protests by the low income

residents. The fact is that most direct victims of pollution

associated with small units are poor or from low income

groups. Their plight attracts little attention as they have

neither the resources nor the time to publicize the

problem.

[Dasgupta: 1997, 291]

In a study of SSEs in Asia, Kent [1991] concluded that

manufacturing SSEs pollute more on a per unit basis than

larger operations. In India alone, small scale industry is

suspected of contributing 60% to 65% of total industrial

pollution. [MSG Environmental Services: 1999, 3] Box 2.3

outlines a number of the SSEs identified in a UNDP study

in Lima (Peru), Harare (Zimbabwe), Bombay (India) and

Leon (India), and the hazardous materials they employ in

the production process.

CIDA-sponsored studies in India [MSG Environmental

Services: 1999] and Bangladesh [Child: 1998] support the

contention that there are a variety of SSEs having

significant negative environmental impacts. The Indian

study identified, among others, the following SSEs and

their main environmental impacts:

Water-related environmental impacts: Starch

production, rice mills, coffee, food processing, agro-

residue, paper mills, textile dyeing and printing, tanneries,

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

25

Box 2.3 Pollutants and Hazardous Residues from Small Scale Industries in

Developing

Countries

INDUSTRY PROCESS HAZARDOUS RESIDUES

Bricks Chronium, fluoride, sulphur, dioxide

Textile dyeing & finishing Cyanide, dyes, oils, resins, sodium hypochlorite, caustic soda, sodium carbonate

polyphosphates

Canning Alkalis, bleach, solvents, wax

Glass and ceramics Arsenic, barium, manganese, selenium

Dry cleaning Solvents, bleach

Dye formulations Tin, zinc

Metal mechanics & metal finishing Caustic soda, sulphuric acid, iron oxide, zinc, solvents

Metal plating Polyphosphates, cyanide, caustic soda, chromium, zinc, carbonates, detergents

Automotive services & machine shops Burnt oil, oil adsorbents, solvents

Pickling Acid, metal, salts

Battery recovery Lead, cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, acids, mercury, methanol

Paper recycling Methanol, mercury, titanium, zinc, wax pesticide formulations, zinc, copper,

fluoride, organic phosphorus, phenol

Tanning Chronium, arsenic, sulphates bicarbonates, formaldehyde

Photography Cyanide, silver, phenols, mercury, alkalis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-32-320.jpg)

![chemicals (including drugs and pharmaceuticals) and

electroplating

Energy and air pollution-related

environmental impacts: Bakeries, clay bricks,

ceramics, glass, foundry, steel re-rolling mills and

refractories

Workplace health and safety problems: Majority

of SSEs, especially chemicals, clay bricks, ceramics, glass,

foundry and plastics

[MSG Environmental Services: 1999, 4]

Small scale brickmaking has an notorious reputation for

being highly polluting. Dirty fuel sources from burning

tires, plastics and debris, and other forms of waste, are not

uncommon [see Blackman: 2000]. Box 2.8.2 looks at the

tannery industry in Kasur, Pakistan, and the attempts of

one NGO to help children and their families face the

often horrific consequences of working in and living close

to small scale tanneries. The case study is significant for a

number of reasons, but most notably for highlighting the

work of one of the few NGOs working in the SSE sector

on environmental issues. This topic will be elaborated

upon in the next chapter.

2.8.1 HBEs and the Environment

Although most HBE activity can be described as

environmentally benign [see Napier et al.: 2000], there can

be HBE activity that is highly problematic from an

environmental and safety standpoint. In Semrang,

Indonesia, there are 41 key HBE economic clusters. Of

those, six clusters — food processors (tapioca crackers,

fermented soybean cake makers), upholstery and metal

household utensil manufacturers, brickmakers and

smoked fish operations — were found to be highly

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

26

Box 2.5 Work Standards for Home Based Beedi Makers

In India, there are 35 million beedi rollers and 17,000 tobacco processors making hand rolled beedi cigarettes. Although 90%

of the workers are women, the trade is controlled entirely by men. In a study of beedi workers, the homes were found to

be in poor condition, with barely enough space for all family members. The homes were damp, usually full of smoke, and had

open drains outside full of discarded and stinking beedis. Only 50% of the houses had electricity, and the women were obliged

to work using the inadequate light provided by kerosene lamps. [Bezborouah: 1985 quoted in Tipple: 1993, 531] Exposure

to nicotine by beedi workers has been known to cause tobacco poisoning. Exposure to tobacco dust by beedi workers leads

to irritation in the eyes, conjunctivitis, rhinitis and interference of the mucosal surface. Pregnant women have exhibited

abnormal foetal growth.

[Carr-Harris: 13]

polluting. They impact negatively on local water supply

and produce unacceptable levels of waste.

[Untari et al.: 2000]

Auto repair, small scale foundries and other manufacturing

activity are other types of HBEs that can create

environmental hazards. In addition, OHS standards are a

major issue with many sectors of HBE activity [see Singh

and Girish: 2000 and Panda: 2000]. For example, Box 2.5

describes the situation of home based Indian beedi

(cigarette) makers. Electronics and computers, other

potential hazardous sectors, are two areas of growth of

HBE activity in the world. Throughout the world, large

companies are contracting out to home based workers to

circumvent environmental and safety standards.

[Baines: 2000]

Perhaps the most crucial environmental issue facing HBEs

is the issue of the appropriate use of space. Although

family members and neighbours are very tolerant of the

noise and the spatial imposition of HBEs, at some level

transforming bedrooms and living rooms into HBE

operations must compromise the choices one can make,

and in some cases create conflict. Clearly some forms of

HBE are ill suited for the kind of space and conditions that

a home offers. This is especially true for small, poorly

constructed and ventilated dwellings.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-33-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

27

Box 2.6 Quarrying in Sao Paulo

The small scale mining industry, which surrounds Sao Paulo, Brazil, has a long tradition. With the spread and development of

Sao Paulo, the environmentally problematic mining activity has come under stronger scrutiny. When it came time to act, a

bureaucratic nightmare was discovered. Eighteen government bodies — federal and local — had responsibilities for overseeing

the different aspects of the mining activities in the metropolitan region of Sao Paulo.

Economic and environment authorities responsible for small scale enterprises are separate entities, and co-operation and co-

ordination between the different departments proved to be highly problematic. For example, there was a conflict between

the land use plan for the city put forward by the government of the state of Sao Paulo, and a similar plan put forward by the

municipal government — i.e., a mining site was legal in one plan, but illegal in the other. Furthermore, the environmental

assessment code designed to cover small scale mining is the same as used to measure the environmental impact of large scale

dams and mining productions.

[Werna: 1997, 391-393]

The most contentious issue with home based work is that

it is carried out privately and escapes closer scrutiny. The

field of research in home based entrepreneurship is

growing. Hopefully this will lead to new insights into

understanding and mitigating HBE environmental

problems.

2.8.2 Local Government and the

Environmental Standards of SSEs

At the local level, there can be a complete absence of

policy, legislation, regulation and administrative machinery

regarding the environmental standards of SSEs.

Increasingly, the lack of appropriate environmental

management capacity is becoming a source of conflict

between local governments and SSEs. Unable to respond

to challenging situations, the tendency is for local

governments to react in an impulsive fashion.

The examples of Sao Paulo [Box 2.6] and Delhi [Box 2.7],

although extreme, are indicative of two different areas

where conflicts are arising more frequently. In the Indian

example, the government decision to close down

polluting SSEs ended up having more negative impacts

than could have been foreseen. In 2000, a similar

crackdown on SSEs led to what was described as the

most violent protest in India in recent times. [Statesman

New Service: 2000] Sections of Delhi were closed down

as the protest by workers and entrepreneurs turned into

scattered rioting. Ingenuity and creativity are required to

help municipal authorities develop the skills and resources

necessary to help SSEs master the environmental effects](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-34-320.jpg)

![Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

28

Box. 2.7 Local Indian Government and Polluting SSEs

In Delhi in 1996, small scale industries, employing on average 20 people, were hit by a series of court orders requiring them

to take measures to reduce pollution. The results: 1,328 industries were closed down and ordered to move out of Delhi;

90,000 units were notified for relocation; and, factories in 28 industrial estates were ordered to participate in setting up central

effluent treatment plants (CETP). The Delhi Master Plan recommended the closure and relocation from Delhi of all units using

or producing hazardous and noxious products. The process involved relocation and the purchase of vast tracts of land to move

away from ‘non conforming areas’.

In terms of gains, some reduction in local ambient pollution will have taken place with the closure of these units. Most of the

units dealing in hazardous and toxic raw materials and products were located in very densely populated areas.

On the negative side, estimates are that as many as 125,000 people lost work. Relocating firms had very fixed and negative

views on the relations between industry and environment. None of the relocating firms expect to upgrade or change the

present technology to reduce pollution. Any measures taken will be to expand production or to increase productivity of the

existing technology.

Some firms had to install end of pipe pollution abatement equipment. Consequently, they have come to regard environmental

expenditure as unproductive and unnecessary. Not only are these measures ineffective, as they are operated only for the

benefit of visitors and inspectors, the perception it is generating has serious implications for long term environmental

improvements.

Given the poisoned atmosphere, simple cost effective alternatives were ignored. The majority of the factory owners who have

applied for land for relocation generally operate from leased premises or would like to expand their production. Relocation

thus provides an opportunity to expand production and increase profit based on the same polluting technology.

The outcome of the present policies are reinforcing trends that work against the development of a more environmentally

effective and socially acceptable policy. Relevant conclusions are:

1. It is distracting attention from the main sources of urban pollution.

2. It is dispersing pollution instead of reducing it.

3. It is discouraging SSEs to change to cleaner technology.

4. A consequence of pushing clean-up measures is that none of the firms made the link between economic gains and

environmental improvements. Increase in profitability through improved energy use, better material recovery and

reduction of waste are non issues.

5. It is ignoring social issues in the name of the environment.

6. The judicial orders, while they have created some environmental awareness, have not provided solutions. On the contrary,

they have reinforced trends which could impede and delay the introduction of improved environmental management and

governance practices.

[Dasgupta:1998, 1-12]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/55a2a375-7f2f-4ad4-8b3c-305b500eee1e-150401134609-conversion-gate01/85/Reinventing-the-City-35-320.jpg)

![[Fernandez: 1997] However, there are recycling sectors

where the environmental implications are of great

concern. Battery and plastic recycling are two SSE sectors

that can operate with minimal or no environmental

procedures in place. The example of battery recycling in

India in Box 2.8 provides insight into the possible

environmental risks related to recycling.

Why so many SSEs are engaged in unsafe recycling activity

is of course a matter of economic survival. As Dasgupta

points out: "banning these activities as many

environmentalists wish to, may be environmentally

advantageous but carries enormous social costs."

[Dasgupta: 1997] The answer is to develop appropriate

policies and technologies to deal with the environmental

ills of recycling on a small scale. The work of the

Netherlands-based WASTE is the sort of effort that must

be favoured to ensure better SSE recycling practices.

WASTE promotes pilot projects and research into

recycling activity by urban SSEs and promotes discussion

on the topic through an electronic newsletter. (see:

http://www.waste.nl)

2.8.4 Environmental Problems in Peri-

Urban Zones

The blurring distinctions between urban, peri-urban and

rural is not without problems. As Birley and Lock note,

the peri-urban zone can be viewed as a "mosaic of

Reinventing the City: The Role of Small Scale Enterprise

30

Box 2.8 Battery Recycling in Calcutta, India

The recycling sector employs thousands of workers, directly and indirectly. In one area of Calcutta alone, there

are reported to be 210 battery breaking and lead smelting units. The used batteries are broken down to extract

the lead plates; this lead is then smelted and made into ingots to be sold to industry. The process of lead smelting

is the primary source of air pollution.

Lead extraction process

The plastic shell of the battery is cracked open and the battery plate removed. The wastes generated at this

stage are diluted sulphuric acid and distilled water. The lead plates are then mixed with charcoal and smelted in

crude furnaces. The furnace is normally a simple brick structure with four vattis (firing pits). Each vatti has a

door through which it is fired. There are no walls separating the four vattis. This means that opening any one

door affects the efficiency of all the others. Furthermore, all four are connected to the same chimney stack. The

lead which separates from the slag is collected and made into ingots. The slag is stored until a substantial amount

has built up. It is then resmelted several times for further extraction.

The very crude methods and the outdated technology used give rise to pollution at several points in the process:

• There is a high level of noise when the batteries are broken up.

• Sulphuric acid is released when batteries are broken up; this finds its way into drains and the surrounding areas,

leading to land and water contamination.

• Sulphur dioxide and carbon monoxide are released during the smelting process.

• Lead oxide forms a major part of the suspended particles released and the fine dust is easily carried by the

wind.

• Inefficient use of the furnace results in excessive smoke and pressure in the chimney stack, forcing some of the

smoke back into the workplace.