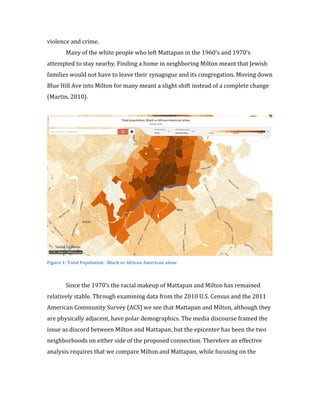

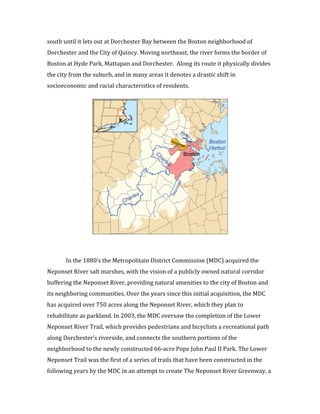

This document summarizes a paper analyzing opposition to a proposed bridge connecting the predominantly black Boston neighborhood of Mattapan to the majority white suburb of Milton. The paper argues that residents opposing the bridge are defending a "white spatial imaginary" and the invisibility of whiteness as the dominant racial identity. While opponents claim concerns over property values and crime, the paper asserts their resistance has underlying racial motivations rooted in historical defenses of spaces characterized by whiteness. Mattapan and Milton historically saw racial shifts in the mid-20th century as black families moved into Mattapan homes vacated by white Jewish families, changing the racial demographics of the neighborhoods.