This document provides an overview of principles of financial accounting. It covers topics such as the accounting cycle for service businesses using both cash and accrual bases of accounting. It also discusses the accounting cycle for merchandising businesses, including basic merchandising transactions under both perpetual and periodic inventory systems. Additionally, it explores assets like inventory and cash in more detail. The document is intended to teach students the fundamentals of recording and reporting financial information according to generally accepted accounting principles.

![Page | 267

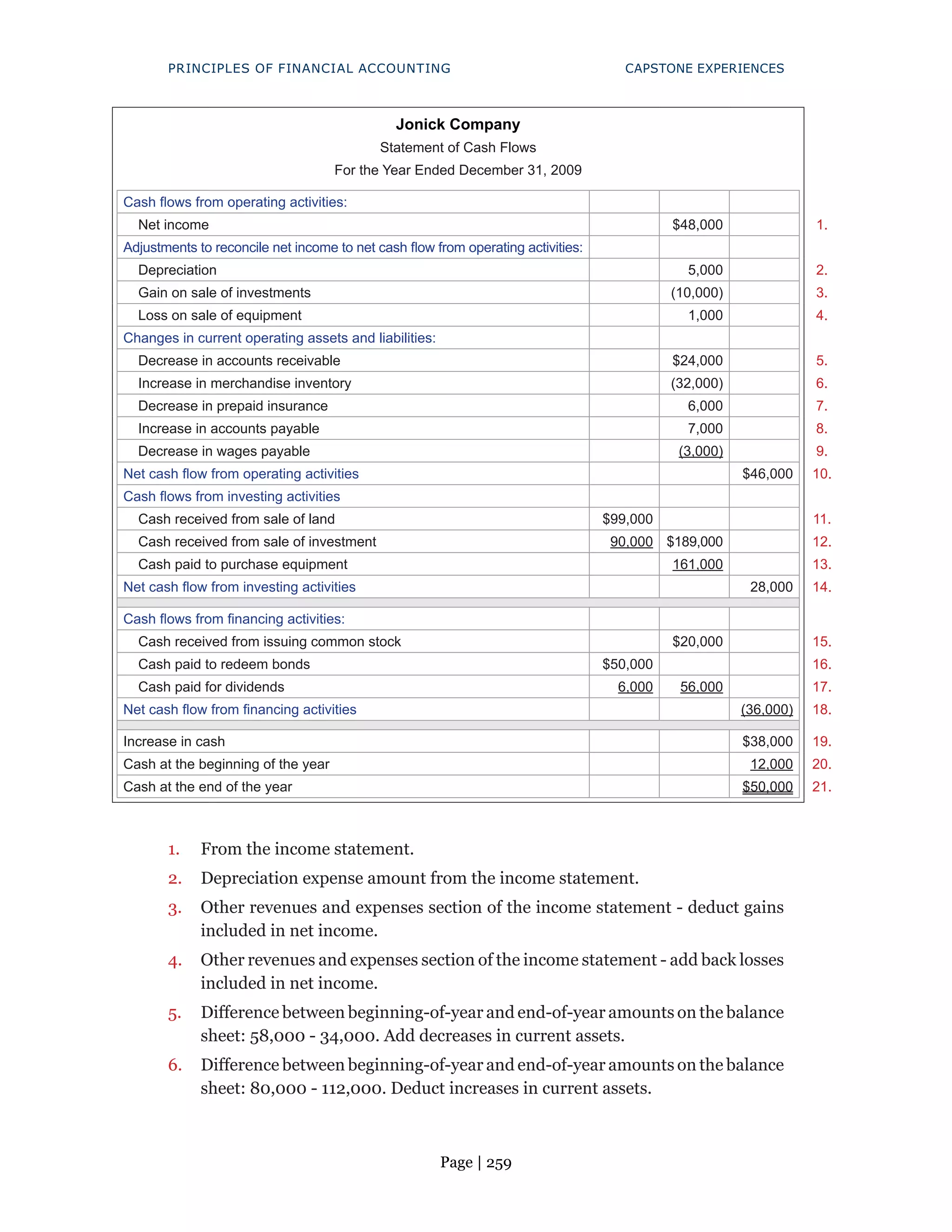

PRINCIPLES OF FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING CAPSTONE EXPERIENCES

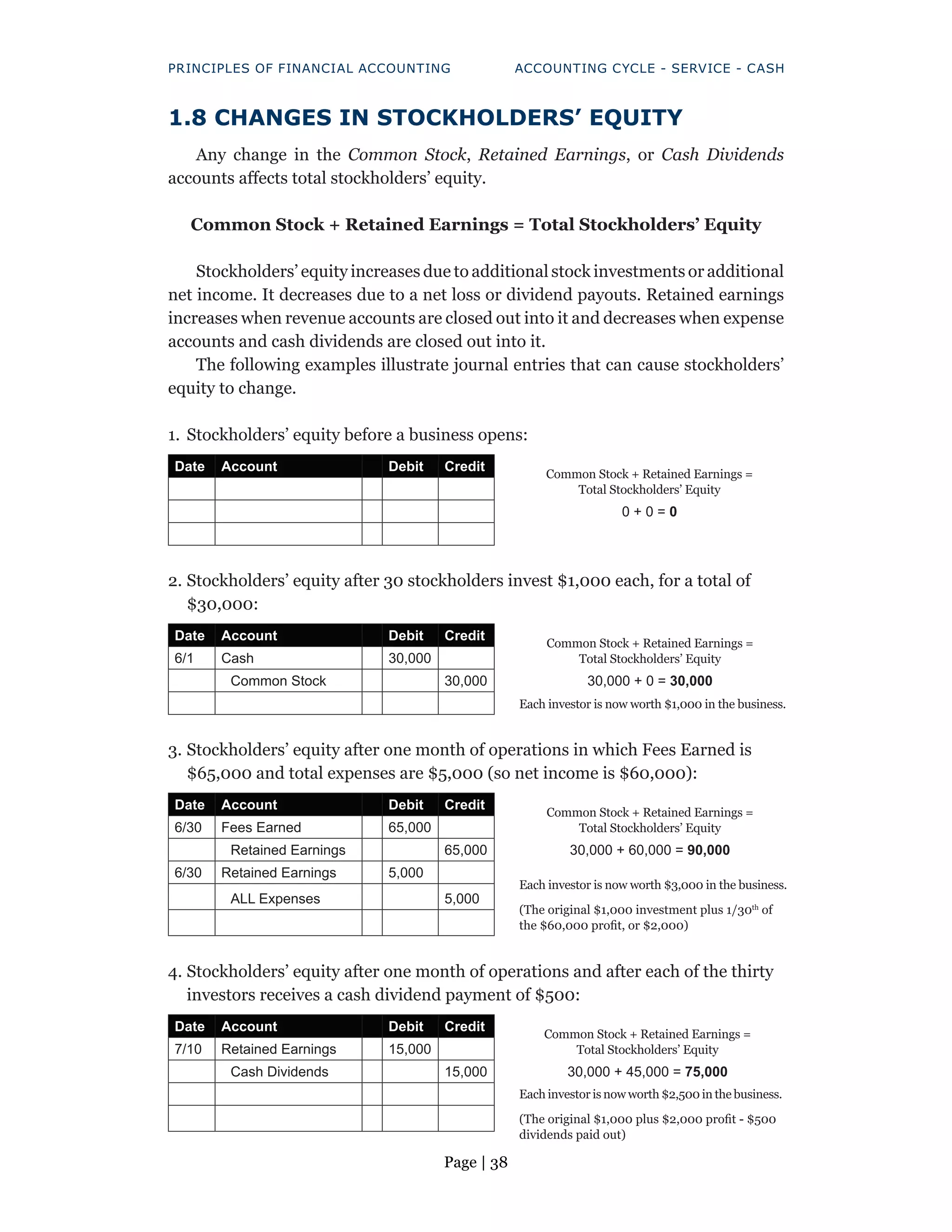

Jonick Company

Comparative Balance Sheet

December 31, 2019 and 2018

End 2019 End 2018

Liabilities

Cash dividends payable 5,000 8,000

Bonds payable 0 50,000

Stockholders’ Equity

Common stock 140,000 125,000

Paid-in capital in excess of par 30,000 25,000

Retained earnings 158,000 113,000

If a long-term liability or stockholders’ equity account balance increases from

one year to the next, it means that more must have been borrowed or received from

investors and there may have been a cash inflow. Similarly, if a long-term liability

account balance decreases from one year to the next, it means that it was repaid

and there was a cash outflow. To help determine the amount of cash received or

paid, refer to the journal entry for each transaction.

Cash flows from financing activities:

Cash received from issuing common stock $20,000

Cash paid to redeem bonds $50,000

Cash paid for dividends 6,000 56,000

Net cash flow from financing activities (36,000)

6. For stock issuances, add the increase in Common Stock + the increase in Paid-

in Capital in Excess of Par to determine the amount of cash inflow [($140,000

- $125,000) + ($30,000 - $25,000)].

7. Cash paid for dividends is calculated as follows:

Beginning Cash Dividends Payable balance + Cash dividends declared –

ending Cash Dividends Payable balance

Cash dividends declared is found on the retained earnings statement. In this

case the calculation is $8,000 + $3,000 - $5,000 = $6,000.

Each financing activity transaction is listed on its own line on the statement

of cash flows. Cash inflows are listed first and each begins with “Cash received

from…” Cash outflows follow and each begins with “Cash paid for…” If there is

more than one inflow, they are subtotaled in the middle column. The same is true

for more than one outflow.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/principles-of-financial-accounting-230110084210-36bae0ff/75/Principles-of-Financial-Accounting-pdf-277-2048.jpg)