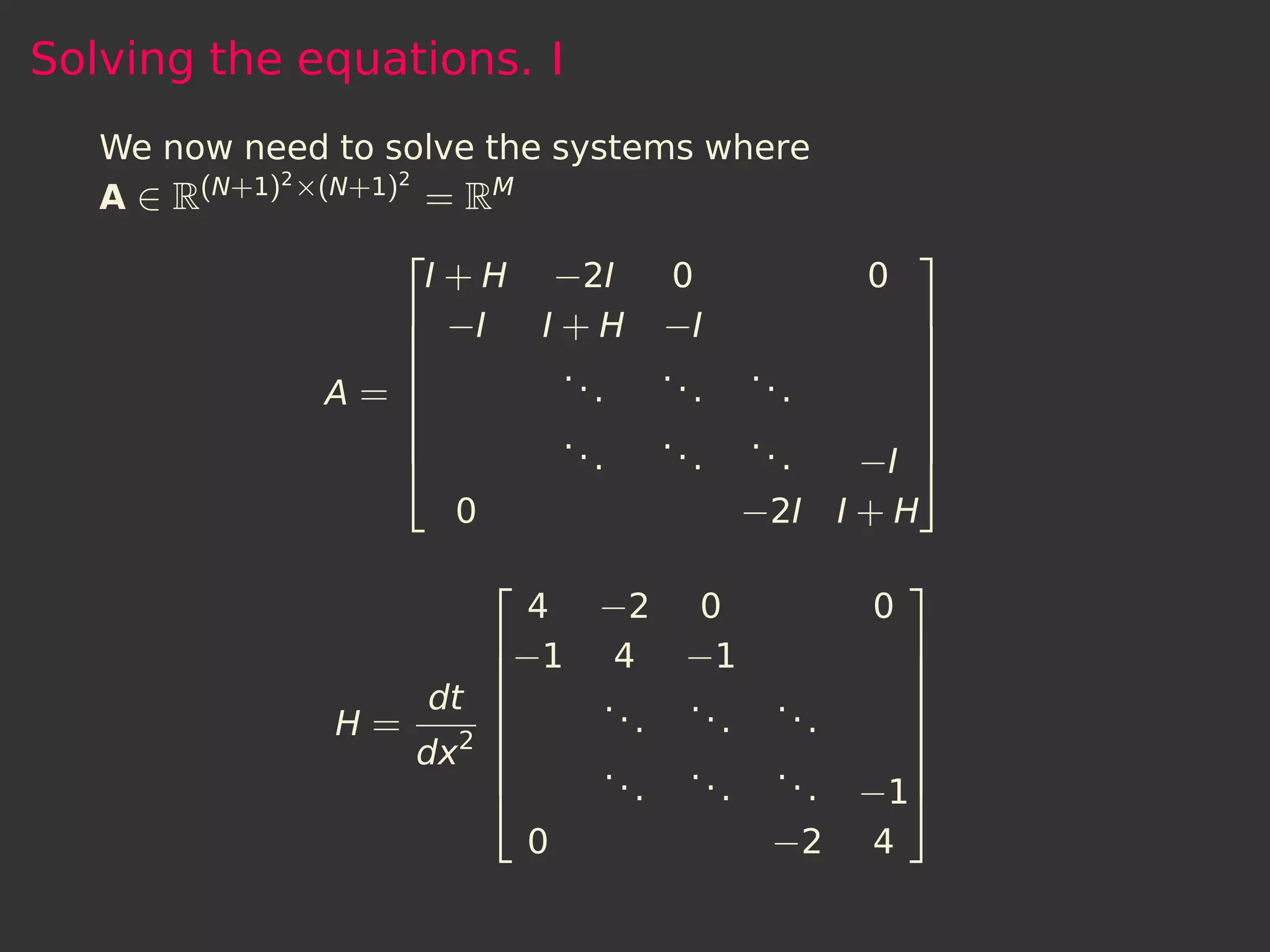

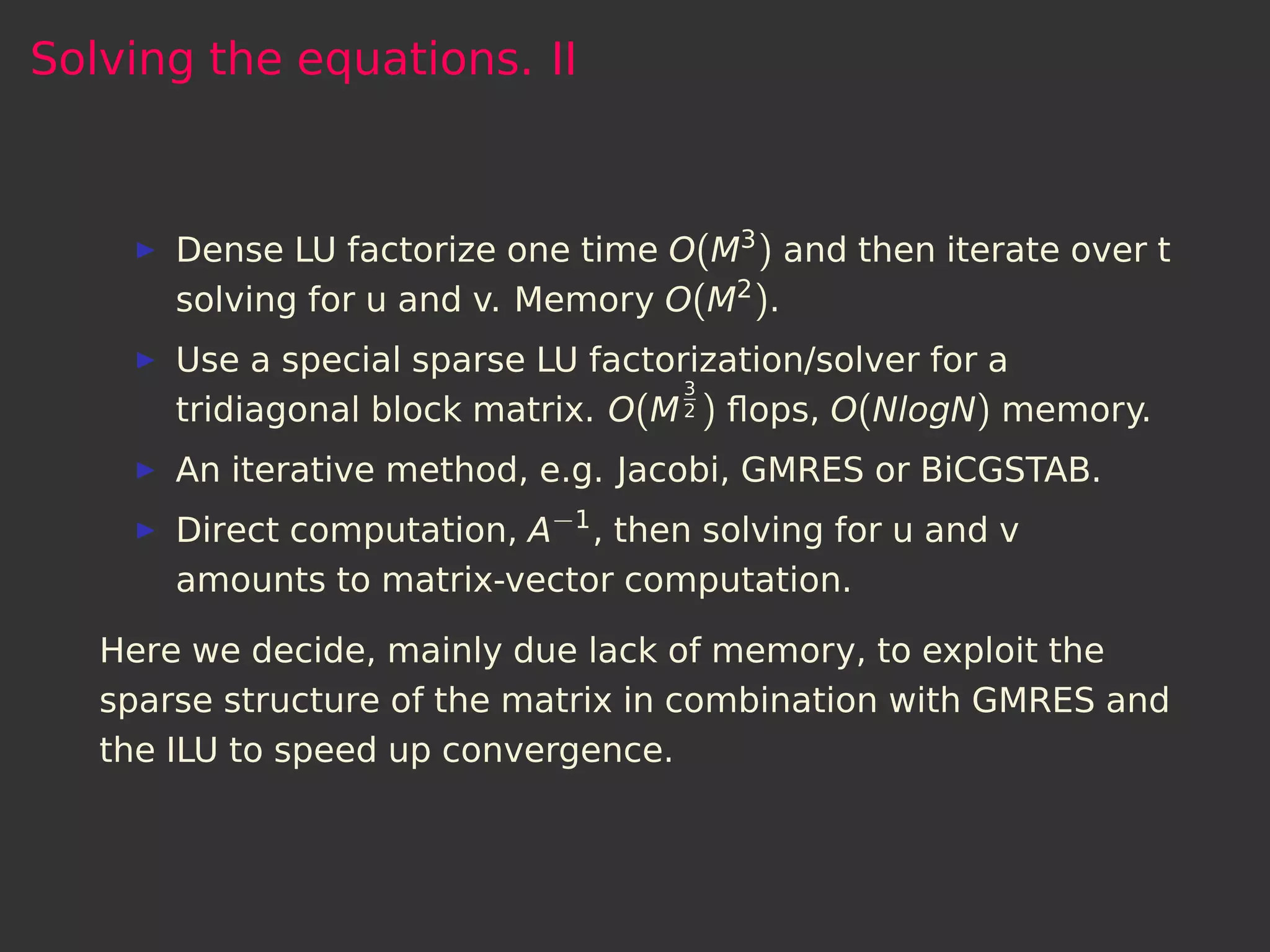

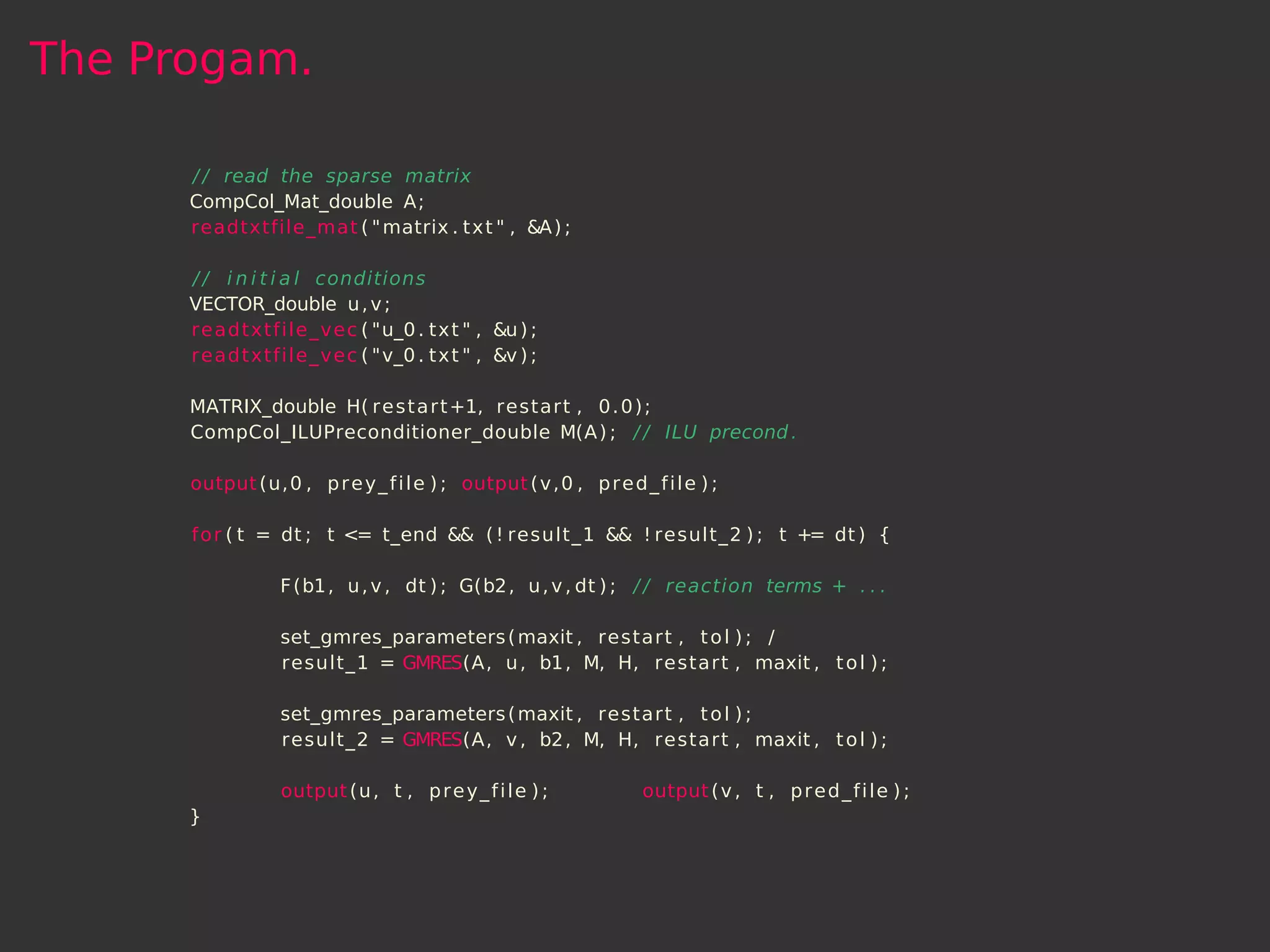

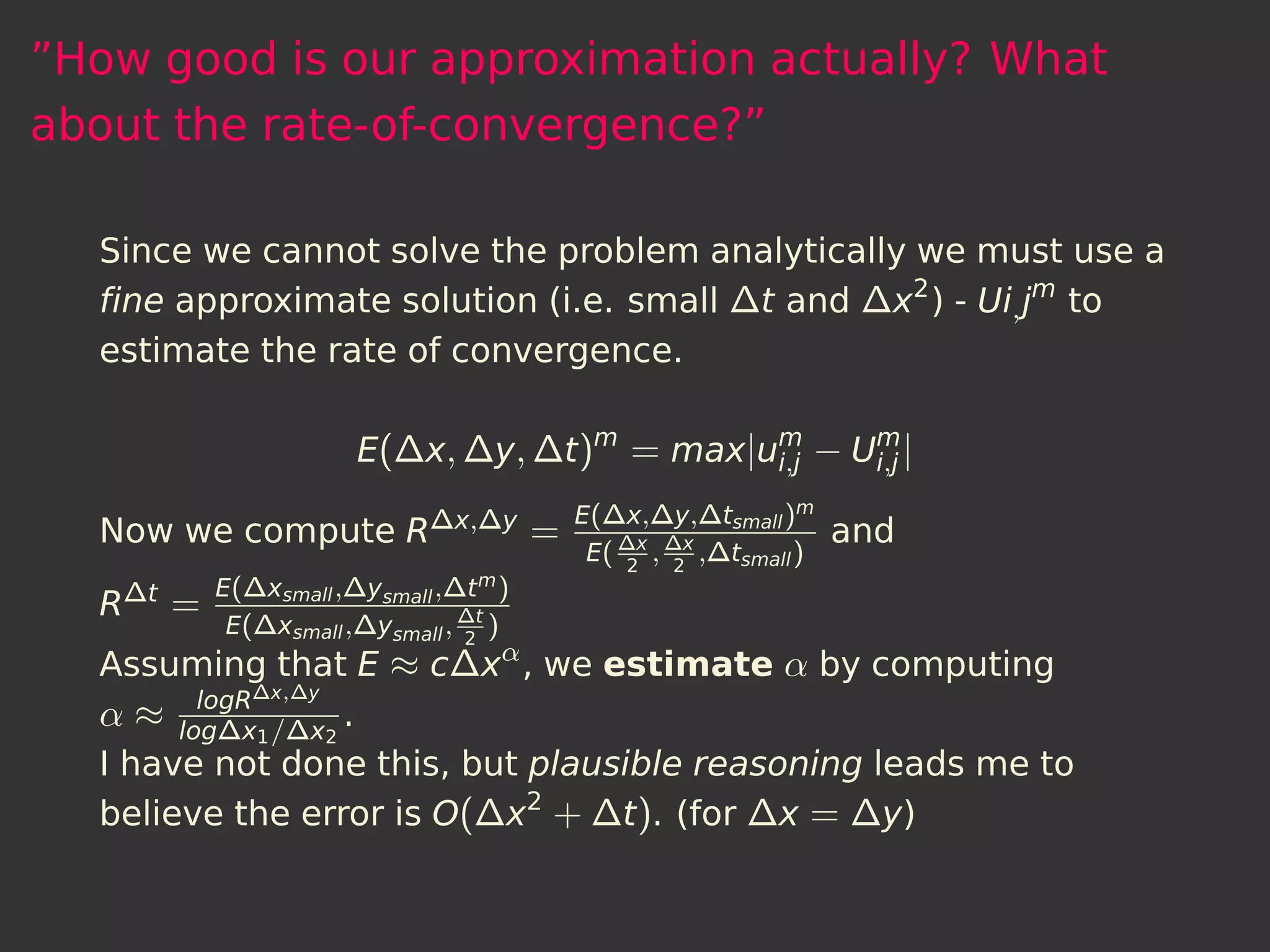

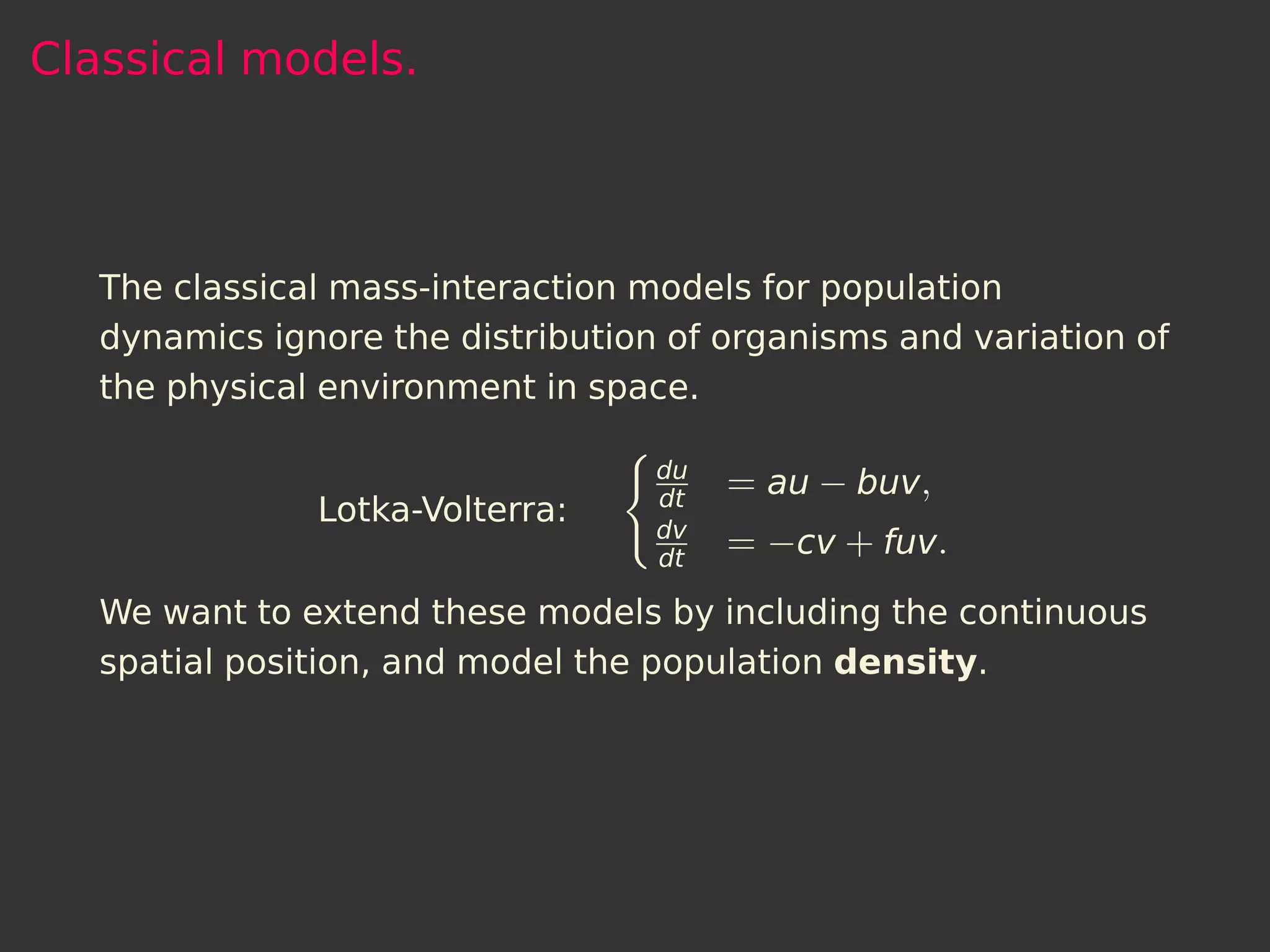

This document summarizes a presentation on numerically solving spatiotemporal models from ecology by implementing an implicit finite difference method in C++. It discusses classical population dynamics models, extending these to include continuous spatial position by using reaction-diffusion systems. It describes discretizing the domain and deriving finite-difference schemes, then solving the equations using GMRES with an ILU preconditioner. Questions addressed include convergence rates and modeling plankton dynamics.

![Dimensionless form and discretization of the domain.

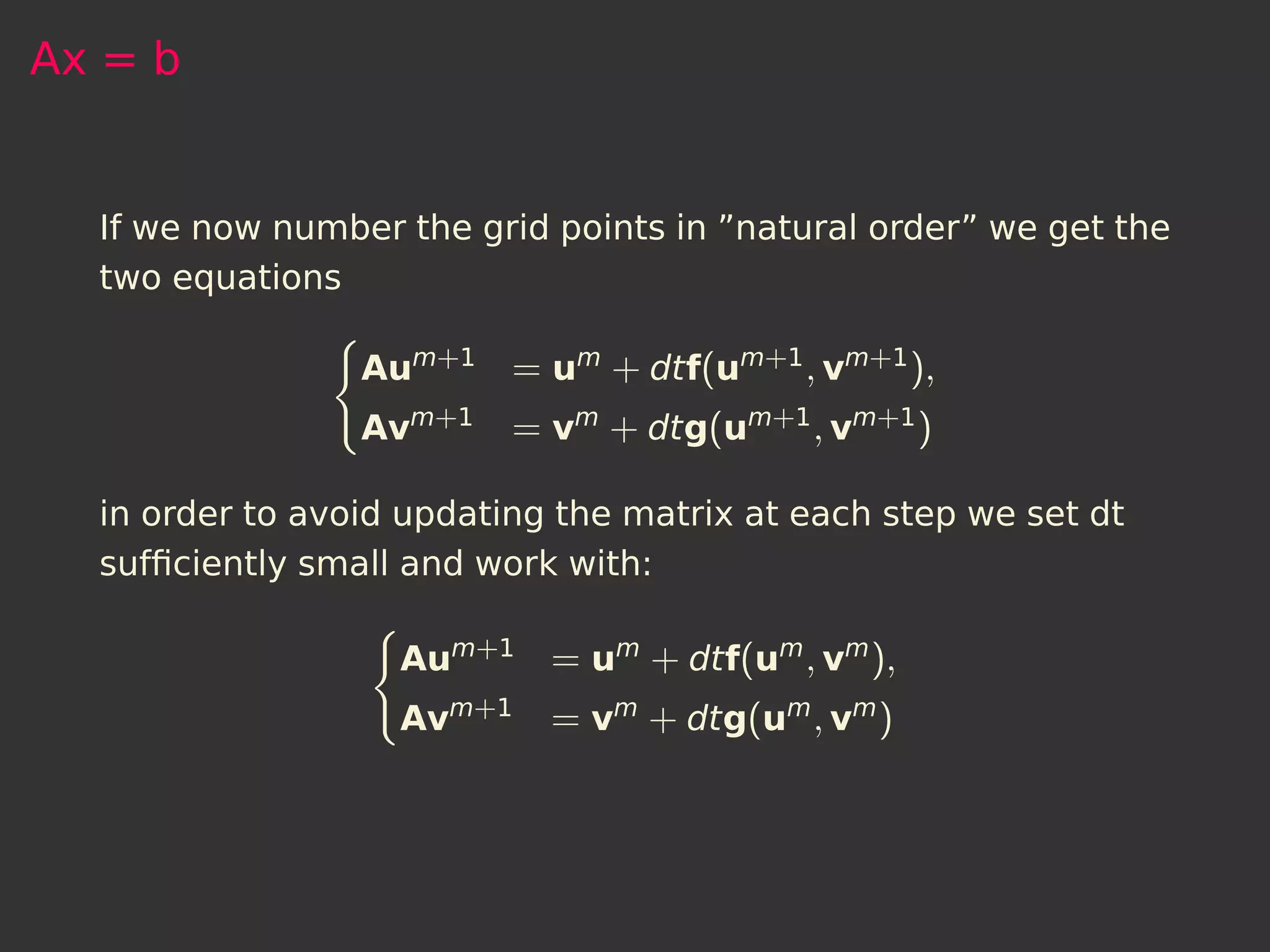

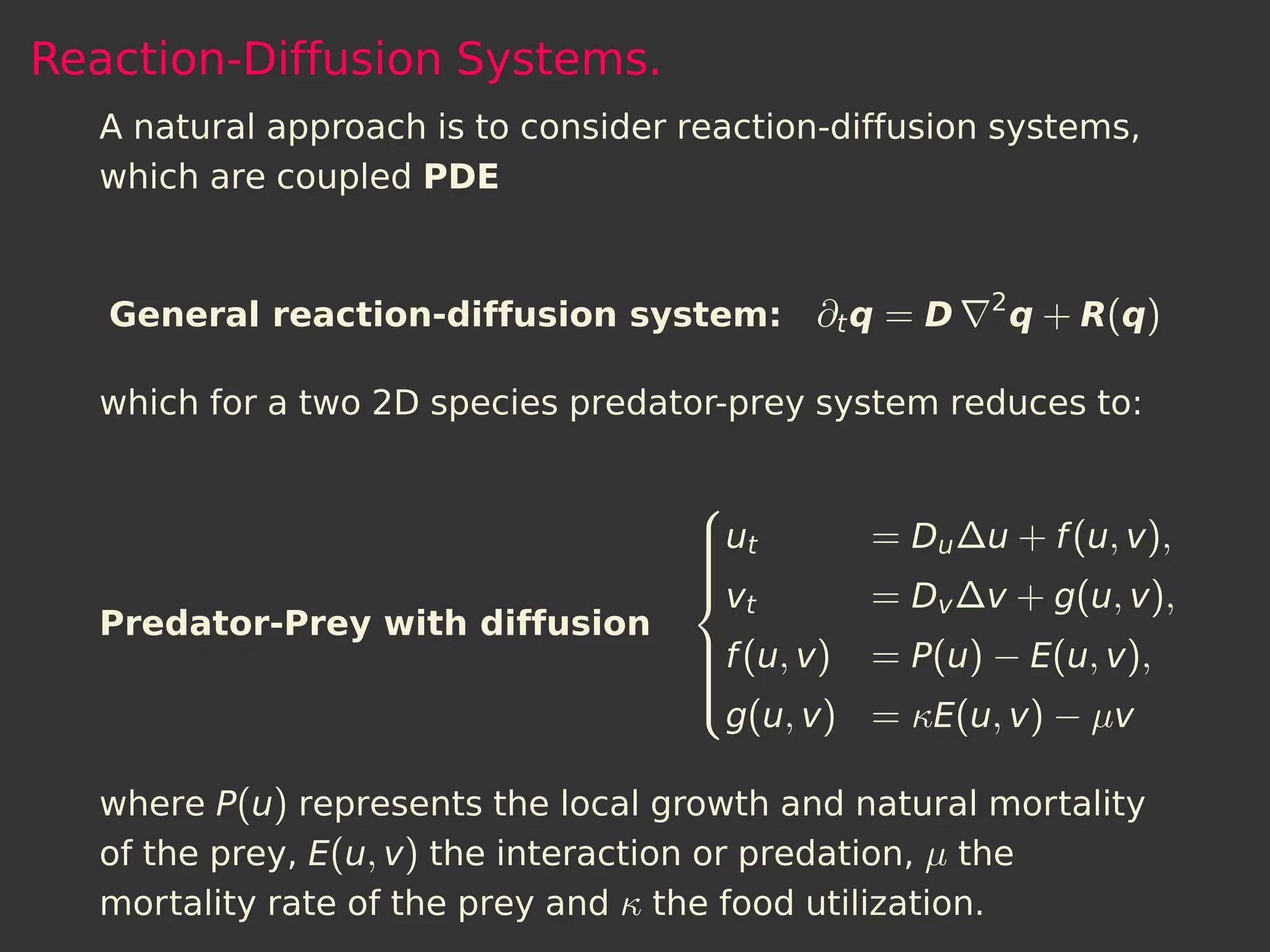

A specific choice for P(u),E(u, v), κ and µ is used to model a

Zooplankton-Phytoplankton aquatic community, here in

dimensionless form.

uv

ut

= ∆u + u(1 − u) − u+ h

,

= ∆v + k uuvh − mv,

v

t +

Plankton interations:

u · n = 0, (x, y) ∈ ∂Ω,

v · n = 0, (x, y) ∈ ∂Ω

We discretize space Ω = [a, b]2 by choosing a finite number of

equally spaced points, (xi , yj ) = (i∆x, j∆y), and time by a

countable number of points 0 = t0 , t1 , . . . , where tm = m∆t.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-130204035918-phpapp02/75/Numerical-solution-of-spatiotemporal-models-from-ecology-4-2048.jpg)