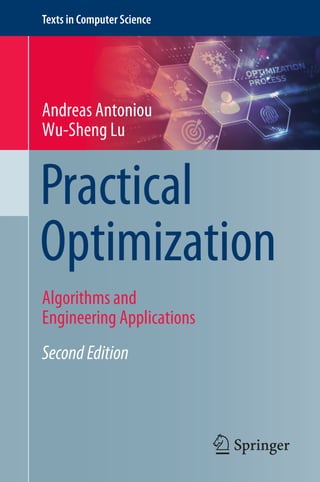

Practical Optimization: Algorithms and Engineering Applications 2nd Edition Andreas Antoniou

Practical Optimization: Algorithms and Engineering Applications 2nd Edition Andreas Antoniou

Practical Optimization: Algorithms and Engineering Applications 2nd Edition Andreas Antoniou

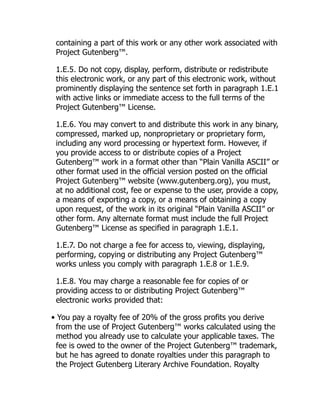

![1.1 Introduction 3

Fig.1.1 Contour plot of

f (x1, x2)

A

10

f (x , x ) = 0

1 2

f (x , x ) = 50

1 2

1

x

2

x

20

30

40

50

each other, and must be adjusted simultaneously to yield the optimum performance

criterion.

The most important general approach to optimization is based on numerical meth-

ods. In this approach, iterative numerical procedures are used to generate a series

of progressively improved solutions to the optimization problem, starting with an

initial estimate for the solution. The process is terminated when some convergence

criterion is satisfied. For example, when changes in the independent variables or the

performance criterion from iteration to iteration become insignificant.

Numerical methods can be used to solve highly complex optimization problems

of the type that cannot be solved analytically. Furthermore, they can be readily

programmed on the digital computer. Consequently, they have all but replaced most

other approaches to optimization.

The discipline encompassing the theory and practice of numerical optimization

methods has come to be known as mathematical programming [1–5]. During the past

40 years, several branches of mathematical programming have evolved, as follows:

1. Linear programming

2. Integer programming

3. Quadratic programming

4. Nonlinear programming

5. Dynamic programming

Each one of these branches of mathematical programming is concerned with a spe-

cific class of optimization problems. The differences among them will be examined

in Sect.1.6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-30-320.jpg)

![4 1 The Optimization Problem

1.2 The Basic Optimization Problem

Before optimization is attempted, the problem at hand must be properly formulated.

A performance criterion F must be derived in terms of n parameters x1, x2, . . . , xn

as

F = f (x1, x2, . . . , xn)

F is a scalar quantity which can assume numerous forms. It can be the cost of a

product in a manufacturing environment or the difference between the desired per-

formance and the actual performance in a system. Variables x1, x2, . . . , xn are the

parameters that influence the product cost in the first case or the actual performance in

the second case. They can be independent variables, like time, or control parameters

that can be adjusted.

The most basic optimization problem is to adjust variables x1, x2, . . . , xn in

such a way as to minimize quantity F. This problem can be stated mathematically

as

minimize F = f (x1, x2, . . . , xn) (1.1)

Quantity F is usually referred to as the objective or cost function.

The objective function may depend on a large number of variables, sometimes as

many as 100 or more. To simplify the notation, matrix notation is usually employed.

If x is a column vector with elements x1, x2, . . . , xn, the transpose of x, namely,

xT , can be expressed as the row vector

xT

= [x1 x2 · · · xn]

In this notation, the basic optimization problem of Eq. (1.1) can be expressed as

minimize F = f (x) for x ∈ En

where En represents the n-dimensional Euclidean space.

On many occasions, the optimization problem consists of finding the maximum

of the objective function. Since

max[ f (x)] = −min[− f (x)]

the maximum of F can be readily obtained by finding the minimum of the negative of

F and then changing the sign of the minimum. Consequently, in this and subsequent

chapters we focus our attention on minimization without loss of generality.

In many applications, a number of distinct functions of x need to be optimized

simultaneously. For example, if the system of nonlinear simultaneous equations

fi (x) = 0 for i = 1, 2, . . . , m

needs to be solved, a vector x is sought which will reduce all fi (x) to zero simulta-

neously. In such a problem, the functions to be optimized can be used to construct a

vector

F(x) = [ f1(x) f2(x) · · · fm(x)]T

The problem can be solved by finding a point x = x∗ such that F(x∗) = 0. Very

frequently, a point x∗ that reduces all the fi (x) to zero simultaneously may not](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-31-320.jpg)

![1.2 The Basic Optimization Problem 5

exist but an approximate solution, i.e., F(x∗) ≈ 0, may be available which could be

entirely satisfactory in practice.

A similar problem arises in scientific or engineering applications when the func-

tion of x that needs to be optimized is also a function of a continuous independent

parameter (e.g., time, position, speed, frequency) that can assume an infinite set

of values in a specified range. The optimization might entail adjusting variables

x1, x2, . . . , xn so as to optimize the function of interest over a given range of the

independent parameter. In such an application, the function of interest can be sampled

with respect to the independent parameter, and a vector of the form

F(x) = [ f (x, t1) f (x, t2) · · · f (x, tm)]T

can be constructed, where t is the independent parameter. Now if we let

fi (x) ≡ f (x, ti )

we can write

F(x) = [ f1(x) f2(x) · · · fm(x)]T

A solution of such a problem can be obtained by optimizing functions fi (x) for

i = 1, 2, . . . , m simultaneously. Such a solution would, of course, be approximate

because any variations in f (x, t) between sample points are ignored. Nevertheless,

reasonable solutions can be obtained in practice by using a sufficiently large number

of sample points. This approach is illustrated by the following example.

Example 1.1 The step response y(x, t) of an nth-order control system is required

to satisfy the specification

y0(x, t) =

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎩

t for 0 ≤ t < 2

2 for 2 ≤ t < 3

−t + 5 for 3 ≤ t < 4

1 for 4 ≤ t

as closely as possible. Construct a vector F(x) that can be used to obtain a function

f (x, t) such that

y(x, t) ≈ y0(x, t) for 0 ≤ t ≤ 5

Solution The difference between the actual and specified step responses, which

constitutes the approximation error, can be expressed as

f (x, t) = y(x, t) − y0(x, t)

and if f (x, t) is sampled at t = 0, 1, . . . , 5, we obtain

F(x) = [ f1(x) f2(x) · · · f6(x)]T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-32-320.jpg)

![1.2 The Basic Optimization Problem 7

Several special cases of the L p norm are of particular interest. If p = 1

F ≡ L1 =

m

i=1

| fi (x)|

and, therefore, in a minimization problem like that in Example1.1, the sum of the

magnitudes of the individual element functions is minimized. This is called an L1

problem.

If p = 2, the Euclidean norm

F ≡ L2 =

m

i=1

| fi (x)|2

1/2

is minimized, and if the square root is omitted, the sum of the squares is minimized.

Such a problem is commonly referred to as a least-squares problem.

In the case where p = ∞, if we assume that there is a unique maximum of | fi (x)|

designated F̂ such that

F̂ = max

1≤i≤m

| fi (x)|

then we can write

F ≡ L∞ = lim

p→∞

m

i=1

| fi (x)|p

1/p

= F̂ lim

p→∞

m

i=1

| fi (x)|

F̂

p

1/p

Since all the terms in the summation except one are less than unity, they tend to zero

when raised to a large positive power. Therefore, we obtain

F = F̂ = max

1≤i≤m

| fi (x)|

Evidently, if the L∞ norm is used in Example1.1, the maximum approximation error

is minimized and the problem is said to be a minimax problem.

Often the individual element functions of F(x) are modified by using constants

w1, w2, . . . , wm as weights. For example, the least-squares objective function can

be expressed as

F =

m

i=1

[wi fi (x)]2

so as to emphasize important or critical element functions and de-emphasize unim-

portant or uncritical ones. If F is minimized, the residual errors in wi fi (x) at the end

of the minimization would tend to be of the same order of magnitude, i.e.,

error in |wi fi (x)| ≈ ε

and so

error in | fi (x)| ≈

ε

|wi |

Consequently, if a large positive weight wi is used with fi (x), a small residual error

is achieved in | fi (x)|.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-34-320.jpg)

![8 1 The Optimization Problem

1.3 General Structure of Optimization Algorithms

Most of the available optimization algorithms entail a series of steps which are

executed sequentially. A typical pattern is as follows:

Algorithm 1.1 General optimization algorithm

Step 1

(a) Set k = 0 and initialize x0.

(b) Compute F0 = f (x0).

Step 2

(a) Set k = k + 1.

(b) Compute the changes in xk given by column vector Δxk where

ΔxT

k = [Δx1 Δx2 · · · Δxn]

by using an appropriate procedure.

(c) Set xk = xk−1 + Δxk

(d) Compute Fk = f (xk) and ΔFk = Fk−1 − Fk.

Step 3

Check if convergence has been achieved by using an appropriate criterion, e.g.,

by checking ΔFk and/or Δxk. If this is the case, continue to Step 4; otherwise,

go to Step 2.

Step 4

(a) Output x∗ = xk and F∗ = f (x∗).

(b) Stop.

In Step 1, vector x0 is initialized by estimating the solution using knowledge about

the problem at hand. Often the solution cannot be estimated and an arbitrary solution

may be assumed, say, x0 = 0. Steps 2 and 3 are then executed repeatedly until

convergence is achieved. Each execution of Steps 2 and 3 constitutes one iteration,

that is, k is the number of iterations.

When convergence is achieved, Step 4 is executed. In this step, column vector

x∗

= [x∗

1 x∗

2 · · · x∗

n ]T

= xk

and the corresponding value of F, namely,

F∗

= f (x∗

)

are output. The column vector x∗ is said to be the optimum, minimum, solution point,

or simply the minimizer, and F∗ is said to be the optimum or minimum value of the

objective function. The pair x∗ and F∗ constitute the solution of the optimization

problem.

Convergence can be checked in several ways, depending on the optimization

problem and the optimization technique used. For example, one might decide to

stop the algorithm when the reduction in Fk between any two iterations has become

insignificant, that is,

|ΔFk| = |Fk−1 − Fk| εF (1.2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-35-320.jpg)

![10 1 The Optimization Problem

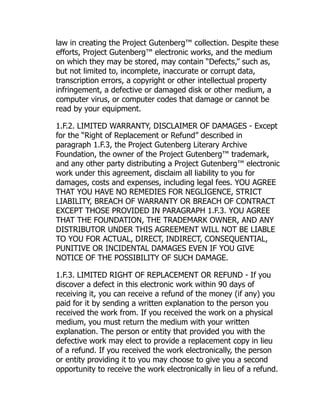

Fig.1.3 The double inverted

pendulum

θ 1

θ 2

Μ

u(t)

A problem that does not entail any equality or inequality constraints is said to be an

unconstrained optimization problem.

Constrained optimization is usually much more difficult than unconstrained opti-

mization, as might be expected. Consequently, the general strategy that has evolved

in recent years towards the solution of constrained optimization problems is to re-

formulate constrained problems as unconstrained optimization problems. This can

be done by redefining the objective function such that the constraints are simultane-

ously satisfied when the objective function is minimized. Some real-life constrained

optimization problems are given as Examples1.2 to 1.4 below.

Example 1.2 Consider a control system that comprises a double inverted pendulum

as depicted in Fig. 1.3. The objective of the system is to maintain the pendulum in the

upright position using the minimum amount of energy. This is achieved by applying

an appropriate control force to the car to damp out any displacements θ1(t) and θ2(t).

Formulate the problem as an optimization problem.

Solution The dynamic equations of the system are nonlinear and the standard practice

is to apply a linearization technique to these equations to obtain a small-signal linear

model of the system as [6]

ẋ(t) = Ax(t) + fu(t) (1.5)

where

x(t) =

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎣

θ1(t)

θ̇1(t)

θ2(t)

θ̇2(t)

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎦ , A =

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎣

0 1 0 0

α 0 −β 0

0 0 0 1

−α 0 α 0

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎦ , f =

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎣

0

−1

0

0

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎦

with α 0, β 0, and α = β. In the above equations, ẋ(t), θ̇1(t), and θ̇2(t)

represent the first derivatives of x(t), θ1(t), and θ2(t), respectively, with respect

to time, θ̈1(t) and θ̈2(t) would be the second derivatives of θ1(t) and θ2(t), and

parameters α and β depend on system parameters such as the length and weight of

each pendulum, the mass of the car, etc. Suppose that at instant t = 0 small nonzero](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-37-320.jpg)

![1.4 Constraints 11

displacements θ1(t) and θ2(t) occur, which would call for immediate control action

in order to steer the system back to the equilibrium state x(t) = 0 at time t = T0. In

order to develop a digital controller, the system model in Eq. (1.5) is discretized to

become

x(k + 1) = x(k) + gu(k) (1.6)

where = I + ΔtA, g = Δtf, Δt is the sampling interval, and I is the identity

matrix. Let x(0) = 0 be given and assume that T0 is a multiple of Δt, i.e., T0 =

KΔt where K is an integer. We seek to find a sequence of control actions u(k) for

k = 0, 1, . . . , K − 1 such that the zero equilibrium state is achieved at t = T0, i.e.,

x(T0) = 0.

Let us assume that the energy consumed by these control actions, namely,

J =

K−1

k=0

u2

(k)

needs to be minimized. This optimal control problem can be formulated analytically

as

minimize J =

K−1

k=0

u2

(k) (1.7a)

subject to: x(K) = 0 (1.7b)

From Eq. (1.6), we know that the state of the system at t = KΔt is determined

by the initial value of the state and system model in Eq. (1.6) as

x(K) = K

x(0) +

K−1

k=0

K−k−1

gu(k)

≡ −h +

K−1

k=0

gku(k)

where h = −K x(0) and gk = K−k−1g. Hence the constraint in Eq. (1.7b) is

equivalent to

K−1

k=0

gku(k) = h (1.8)

If we define u = [u(0) u(1) · · · u(K − 1)]T and G = [g0 g1 · · · gK−1], then the

constraint in Eq. (1.8) can be expressed as Gu = h, and the optimal control problem

at hand can be formulated as the problem of finding a u that solves the minimization

problem](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-38-320.jpg)

![12 1 The Optimization Problem

minimize uT

u (1.9a)

subject to: a(u) = 0 (1.9b)

where a(u) = Gu − h. In practice, the control actions cannot be made arbitrarily

large in magnitude. Consequently, additional constraints are often imposed on |u(i)|,

for instance,

|u(i)| ≤ m for i = 0, 1, . . . , K − 1

These constraints are equivalent to

m + u(i) ≥ 0

m − u(i) ≥ 0

Hence if we define

c(u) =

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

m + u(0)

m − u(0)

.

.

.

m + u(K − 1)

m − u(K − 1)

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

then the magnitude constraints can be expressed as

c(u) ≥ 0 (1.9c)

Obviously, the problem in Eqs. (1.9a)–(1.9c) fits nicely into the standard form of

optimization problems given by Eqs. (1.4a)–(1.4c).

Example 1.3 High performance in modern optical instruments depends on the qual-

ity of components like lenses, prisms, and mirrors. These components have reflecting

or partially reflecting surfaces, and their performance is limited by the reflectivities

of the materials of which they are made. The surface reflectivity can, however, be

altered by the deposition of a thin transparent film. In fact, this technique facilitates

the control of losses due to reflection in lenses and makes possible the construction

of mirrors with unique properties [7,8].

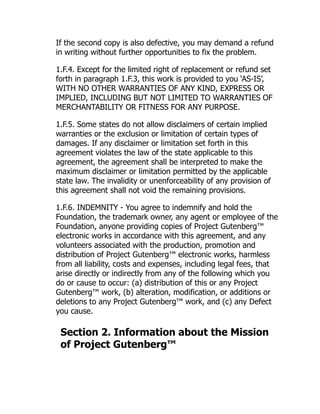

As is depicted in Fig. 1.4, a typical N-layer thin-film system consists of N layers of

thin films of certain transparent media deposited on a glass substrate. The thickness

and refractive index of the ith layer are denoted as xi and ni , respectively. The

refractive index of the medium above the first layer is denoted as n0. If φ0 is the

angle of incident light, then the transmitted ray in the (i − 1)th layer is refracted at

an angle φi which is given by Snell’s law, namely,

ni sin φi = n0 sin φ0

Given angle φ0 and the wavelength of light, λ, the energy of the light reflected

from the film surface and the energy of the light transmitted through the film surface

are usually measured by the reflectance R and transmittance T , which satisfy the

relation

R + T = 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-39-320.jpg)

![1.4 Constraints 13

Fig.1.4 An N-layer

thin-film system

n0

n3

n2

nN

nN+1

layer 1

layer 2

layer 3

x2

x1 n1

Substrate

φ1

φ0

φ2

layer N xn

φN

For an N-layer system, R is given by (see [9] for details)

R(x1, . . . , xN , λ) =

η0 − y

η0 + y

2

y =

c

b

b

c

=

N

k=1

cos δk ( j sin δk)/ηk

jηk sin δk cos δk

1

ηN+1

where j =

√

−1 and

δk =

2πnk xk cos φk

λ

ηk =

⎧

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

nk/ cos φk for light polarized with the electric

vector lying in the plane of incidence

nk cos φk for light polarized with the electric

vector perpendicular to the

plane of incidence

The design of a multilayer thin-film system can now be accomplished as follows:

Given a range of wavelengths λl ≤ λ ≤ λu and an angle of incidence φ0, find

x1, x2, . . . , xN such that the reflectance R(x, λ) best approximates a desired re-

flectance Rd(λ) for λ ∈ [λl, λu]. Formulate the design problem as an optimization

problem.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-40-320.jpg)

![14 1 The Optimization Problem

Solution In practice, the desired reflectance is specified at grid points λ1, λ2, . . . , λK

in the interval [λl, λu]; hence the design may be carried out by selecting xi such

that the objective function

J =

K

i=1

wi [R(x, λi ) − Rd(λi )]2

(1.10)

is minimized, where

x = [x1 x2 · · · xN ]T

and wi 0 is a weight to reflect the importance of term [R(x, λi ) − Rd(λi )]2 in

Eq. (1.10). If we let η = [1 ηN+1]T , e+ = [η0 1]T , e− = [η0 −1]T , and

M(x, λ) =

N

k=1

cos δk ( j sin δk)/ηk

jηk sin δk cos δk

then R(x, λ) can be expressed as

R(x, λ) =

bη0 − c

bη0 + c

2

=

eT

−M(x, λ)η

eT

+M(x, λ)η

2

Finally, we note that the thickness of each layer cannot be made arbitrarily thin or

arbitrarily large and, therefore, constraints must be imposed on the elements of x as

dil ≤ xi ≤ diu for i = 1, 2, . . . , N

The design problem can now be formulated as the constrained minimization problem

minimize J =

K

i=1

wi

eT

−M(x, λi )η

eT

+M(x, λi )η

2

− Rd(λi )2

subject to: xi − dil ≥ 0 for i = 1, 2, . . . , N

diu − xi ≥ 0 for i = 1, 2, . . . , N

Example 1.4 Quantities q1, q2, . . . , qm of a certain product are produced by m

manufacturing divisions of a company, which are at distinct locations. The product

is to be shipped to n destinations that require quantities b1, b2, . . . , bn. Assume

that the cost of shipping a unit from manufacturing division i to destination j is ci j

with i = 1, 2, . . . , m and j = 1, 2, . . . , n. Find the quantity xi j to be shipped

from division i to destination j so as to minimize the total cost of transportation, i.e.,

minimize C =

m

i=1

n

j=1

ci j xi j

This is known as the transportation problem. Formulate the problem as an optimiza-

tion problem.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-41-320.jpg)

![1.4 Constraints 15

Solution Note that there are several constraints on variables xi j . First, each division

can provide only a fixed quantity of the product, hence

n

j=1

xi j = qi for i = 1, 2, . . . , m

Second, the quantity to be shipped to a specific destination has to meet the need of

that destination and so

m

i=1

xi j = bj for j = 1, 2, . . . , n

In addition, the variables xi j are nonnegative and thus, we have

xi j ≥ 0 for i = 1, 2, . . . , m and j = 1, 2, . . . , n

If we let

c = [c11 · · · c1n c21 · · · c2n · · · cm1 · · · cmn]T

x = [x11 · · · x1n x21 · · · x2n · · · xm1 · · · xmn]T

A =

⎡

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

1 1 · · · 1 0 0 · · · 0 · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0 0 · · · 0 1 1 · · · 1 · · · · · · · · · · · ·

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0 0 · · · 0 0 0 · · · 0 · · · 1 1 · · · 1

1 0 · · · 0 1 0 · · · 0 · · · 1 0 · · · 0

0 1 · · · 0 0 1 · · · 0 · · · 0 1 · · · 0

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

0 0 · · · 1 0 0 · · · 1 · · · 0 0 · · · 1

⎤

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

b = [q1 · · · qm b1 · · · bn]T

then the minimization problem can be stated as

minimize C = cT

x (1.11a)

subject to: Ax = b (1.11b)

x ≥ 0 (1.11c)

where cT x is the inner product of c and x. The above problem, like those in Exam-

ples1.2 and 1.3, fits into the standard optimization problem in Eqs. (1.4a)–(1.4c).

Since both the objective function in Eq. (1.11a) and the constraints in Eqs. (1.11b)

and (1.11c) are linear, the problem is known as a linear programming (LP) problem

(see Sect.1.6.1).

Example 1.5 An investment portfolio is a collection of a variety of securities owned

by an individual whereby each security is associated with a unique possible return and

a corresponding risk. Design an optimal investment portfolio that would minimize

the risk involved subject to an acceptable return for a portfolio that comprises n

securities.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-42-320.jpg)

![16 1 The Optimization Problem

Solution Some background theory on portfolio selection can be found in [10]. As-

sume that the amount of resources to be invested is normalized to unity (e.g., 1

million dollars) and let xi represent the return of security i at some specified time in

the future, say, in one month’s time. The return xi can be assumed to be a random

variable and hence three quantities pertaining to security i can be evaluated, namely,

the expected return

μi = E[xi ]

the variance of the return

σ2

i = E[(xi − μi )2

]

and the correlation between the returns of the ith and jth securities

ρi, j =

E[(xi − μi )(x j − μj )]

σi σj

for i, j = 1, 2, . . . , n

With these quantities known, constructing a portfolio amounts to allocating a fraction

wi of the available resources to security i, for i = 1, 2, . . . , n. This leads to the

constraints

0 ≤ wi ≤ 1 for i = 1, 2, . . . , n and

n

i=1

wi = 1

Given a set of investment allocations {wi , i = 1, 2, . . . , n}, the expected return of

the portfolio can be deduced as

E

n

i=1

wi xi

=

n

i=1

wi μi

The variance for the portfolio, which measures the risk of the investment, can be

evaluated as

E

n

i=1

wi xi − E(

n

i=1

wi xi )

2

= E

⎧

⎨

⎩

n

i=1

wi (xi − μi )

⎡

⎣

n

j=1

wj (x j − μj )

⎤

⎦

⎫

⎬

⎭

= E

⎡

⎣

n

i=1

n

j=1

(xi − μi )(x j − μj )wi wj

⎤

⎦

=

n

i=1

n

j=1

E[(xi − μi )(x j − μj )]wi wj

=

n

i=1

n

j=1

(σi σj ρi j )wi wj

=

n

i=1

n

j=1

qi j wi wj

where

qi j = σi σj ρi j](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20986-250315065426-4aaea085/85/Practical-Optimization-Algorithms-and-Engineering-Applications-2nd-Edition-Andreas-Antoniou-43-320.jpg)