This document provides information about a conference titled "First International Conference, OL2A 2021" that was held from July 19-21, 2021 in Bragança, Portugal. It discusses the conference's organization, including its editors, scientific committee members, and topics. The conference focused on optimization, learning algorithms, and applications. It received 134 submissions and selected 52 accepted papers, including 39 full papers.

![Dynamic Response Surface Method

Combined with Genetic Algorithm

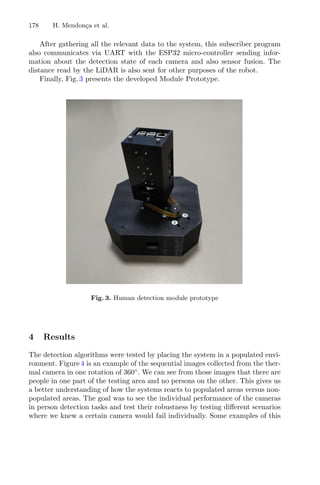

to Optimize Extraction Process Problem

Laires A. Lima1,2(B)

, Ana I. Pereira1

, Clara B. Vaz1

, Olga Ferreira2

,

Márcio Carocho2

, and Lillian Barros2

1

Research Center in Digitalization and Intelligent Robotics (CeDRI), Instituto

Politécnico de Bragança, Campus de Santa Apolónia, 5300-253 Bragança, Portugal

{laireslima,apereira,clvaz}@ipb.pt

2

Centro de Investigação de Montanha (CIMO), Instituto Politécnico de Bragança,

Campus de Santa Apolónia, 5300-253 Bragança, Portugal

{oferreira,mcarocho,lillian}@ipb.pt

Abstract. This study aims to find and develop an appropriate opti-

mization approach to reduce the time and labor employed throughout a

given chemical process and could be decisive for quality management. In

this context, this work presents a comparative study of two optimization

approaches using real experimental data from the chemical engineering

area, reported in a previous study [4]. The first approach is based on the

traditional response surface method and the second approach combines

the response surface method with genetic algorithm and data mining.

The main objective is to optimize the surface function based on three

variables using hybrid genetic algorithms combined with cluster analysis

to reduce the number of experiments and to find the closest value to

the optimum within the established restrictions. The proposed strategy

has proven to be promising since the optimal value was achieved with-

out going through derivability unlike conventional methods, and fewer

experiments were required to find the optimal solution in comparison to

the previous work using the traditional response surface method.

Keywords: Optimization · Genetic algorithm · Cluster analysis

1 Introduction

Search and optimization methods have several principles, being the most rele-

vant: the search space, where the possibilities for solving the problem in question

are considered; the objective function (or cost function); and the codification of

the problem, that is, the way to evaluate an objective in the search space [1].

Conventional optimization techniques start with an initial value or vector

that, iteratively, is manipulated using some heuristic or deterministic process

c

Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

A. I. Pereira et al. (Eds.): OL2A 2021, CCIS 1488, pp. 3–14, 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91885-9_1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-16-320.jpg)

![4 L. A. Lima et al.

directly associated with the problem to be solved. The great difficulty to deal

with when solving a problem using a stochastic method is the number of possible

solutions growing with a factorial speed, being impossible to list all possible

solutions of the problem [12]. Evolutionary computing techniques operate on a

population that changes in each iteration. Thus, they can search in different

regions on the feasible space, allocating an appropriate number of members to

search in different areas [12].

Considering the importance of predicting the behavior of analytical processes

and avoiding expensive procedures, this study aims to propose an alternative

for the optimization of multivariate problems, e.g. extraction processes of high-

value compounds from plant matrices. In the standard analytical approach, the

identification and quantification of phenolic compounds require expensive and

complex laboratory assays [6]. An alternative approach can be applied using

forecasting models from Response Surface Method (RSM). This approach can

maximize the extraction yield of the target compounds while decreasing the cost

of the extraction process.

In this study, a comparative analysis between two optimization methodolo-

gies (traditional RSM and dynamic RSM), developed in MATLAB R

software

(version R2019a 9.6), that aim to maximize the heat-assisted extraction yield

and phenolic compounds content in chestnut flower extracts is presented.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methods used to

evaluate multivariate problems involving optimization processes: Response Sur-

face Method (RSM), Hybrid Genetic Algorithm, Cluster Analysis and Bootsrap

Analysis. Sections 3 and 4 introduce the case study, consisting of the optimization

of the extraction yield and content of phenolic compounds in extracts of chest-

nut flower by two different approaches: Traditional RSM and Dynamic RSM.

Section 5 includes the numerical results obtained by both methods and their

comparative evaluation. Finally, Sect. 6 presents the conclusions and future work.

2 Methods Approaches and Techniques

Regarding optimization problems, some methods are used more frequently (tra-

ditional RSM, for example) due to their applicability and suitability to different

cases. For the design of the dynamic RSM, the approach of conventional meth-

ods based on Genetic Algorithm combined with clustering and bootstrap analysis

was made to evaluate the aspects that could be incorporated into the algorithm

developed in this work. The key concepts for dynamic RSM are presented below.

2.1 Response Surface Method

The Response Surface Method is a tool introduced in the early 1950s by Box

and Wilson, which covers a collection of mathematical and statistical techniques

useful for approximating and optimizing stochastic models [11]. It is a widely

used optimization method, which applies statistical techniques based on special

factorial designs [2,3]. Its scientific approach estimates the ideal conditions for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-17-320.jpg)

![Dynamic RSM Combined with GA to Optimize Extraction Process Problem 5

achieving the highest or lowest required response value, through the design of the

response surface from the Taylor series [8]. RSM promotes the greatest amount

of information on experiments, such as the time of experiments and the influence

of each dependent variable, being one of the largest advantages in obtaining the

necessary general information on the planning of the process and the experience

design [8].

2.2 Hybrid Genetic Algorithm

The genetic algorithm is a stochastic optimization method based on the evolu-

tionary process of natural selection and genetic dynamics. The method seeks to

combine the survival of the fittest among the string structures with an exchange

of random, but structured, information to form an ideal solution [7]. Although

they are randomized, GA search strategies are able to explore several regions

of the feasible search space at a time. In this way, along with the iterations,

a unique search path is built, as new solutions are obtained through the com-

bination of previous solutions [1]. Optimization problems with restrictions can

influence the sampling capacity of a genetic algorithm due to the population

limits considered. Incorporating a local optimization method into GA can help

overcome most of the obstacles that arise as a result of finite population sizes,

for example, the accumulation of stochastic errors that generate genetic drift

problems [1,7].

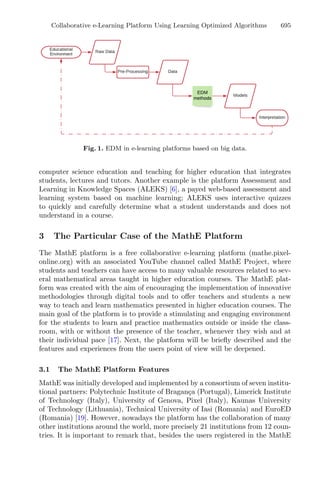

2.3 Cluster Analysis

Cluster algorithms are often used to group large data sets and play an impor-

tant role in pattern recognition and mining large arrays. k-means and k-medoids

strategies work by grouping partition data into a k number of mutually exclusive

clusters, demonstrated in Fig. 1. These techniques assign each observation to a

cluster, minimizing the distance from the data point to the average (k-means)

or median (k-medoids) location of its assigned cluster [10].

Fig. 1. Mean and Medoid in 2D space representation. In both figures, the data are

represented by blue dots, being the rightmost point an outlier and the red point rep-

resents the centroid point found by k-mean or k-medoid methods. Adapted from Jin

and Han (2011) (Color figure online).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-18-320.jpg)

![6 L. A. Lima et al.

2.4 Bootstrap Analysis

The idea of bootstrap analysis is to mimic the sampling distribution of the statis-

tic of interest through the use of many resamples replacing the original sample

elements [5]. In this work, the bootstrap analysis enables the handling of the vari-

ability of the optimal solutions derived from the cluster method analysis. Thus,

the bootstrap analysis is used to estimate the confidence interval of the statis-

tic of interest and subsequently, comparing the results obtained by traditional

methods.

3 Case Study

This work presents a comparative analysis between two methodologies for opti-

mizing the total phenolic content in extracts of chestnut flower, developed in

MATLAB R

software. The natural values of the dependent variables in the

extraction - t, time in minutes; T, temperature in ◦

C; and S, organic solvent con-

tent in %v/v of ethanol - were coded based on Central Composite Circumscribed

Design (CCCD) and the result was based on extraction yield (Y, expressed in

percentage of dry extract) and total phenolic content (Phe, expressed in mg/g

of dry extract) as shown in Table 1.

The experimental data presented were cordially provided by the Mountain

Research Center - CIMO (Bragança, Portugal) [4].

The CCCD design selected for the original experimental study [4] is based

on a cube circumscribed to a sphere in which the vertices are at α distance from

the center, with 5 levels for each factor (t, T, and S). In this case, the α values

vary between −1.68 and 1.68, and correspond to each factor level, as described

in Table 2.

4 Data Analysis

In this section, the two RSM optimization methods (traditional and dynamic)

will be discussed in detail, along with the results obtained from both methods.

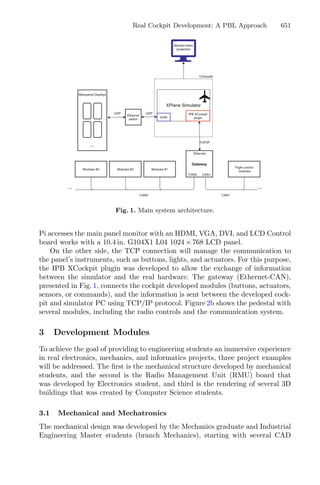

4.1 Traditional RSM

In the original experiment, a five-level Central Composite Circumscribed Design

(CCCD) coupled with RSM was build to optimize the variables for the male

chestnut flowers. For the optimization, a simplex method developed ad hoc was

used to optimize nonlinear solutions obtained by a regression model to maximize

the response, described in the flowchart in Fig. 2.

Through the traditional RSM, the authors approximated the surface response

to a second-order polynomial function [4]:

Y = b0 +

n

i=1

biXi +

n−1

i=1

j1

n

j=2

bijXiXj +

n

i=1

biiX2

i (1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-19-320.jpg)

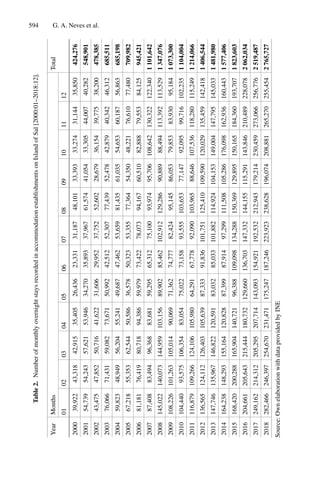

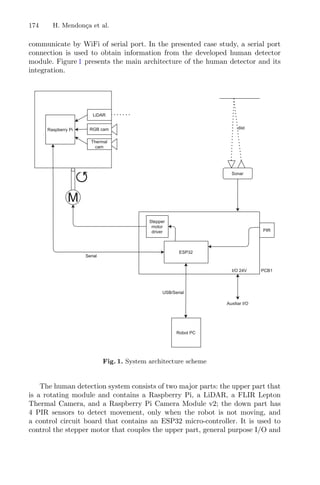

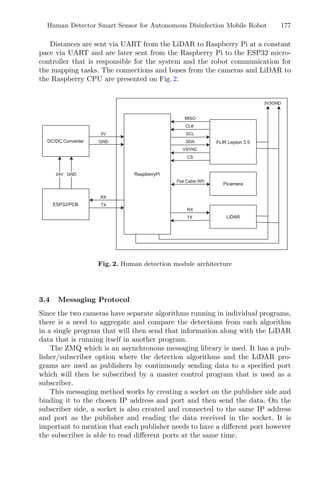

![Dynamic RSM Combined with GA to Optimize Extraction Process Problem 7

Table 1. Variables and natural values of the process parameters for the extraction of

chestnut flowers [4].

t (min) T (◦

C) S (%EtOH) Yield (%R) Phenolic cont.

(mg.g−1

dry weight)

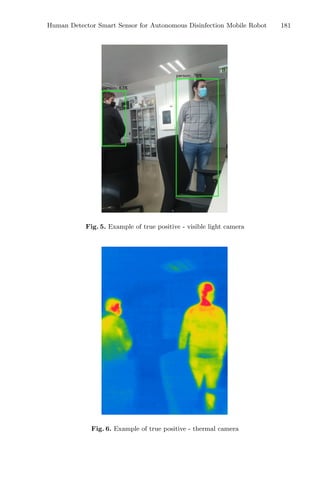

40.30 37.20 20.30 38.12 36.18

40.30 37.20 79.70 26.73 11.05

40.30 72.80 20.30 42.83 36.66

40.30 72.80 79.70 35.94 22.09

99.70 37.20 20.30 32.77 35.55

99.70 37.20 79.70 32.99 8.85

99.70 72.80 20.30 42.55 29.61

99.70 72.80 79.70 35.52 11.10

120.00 55.00 50.00 42.41 14.56

20.00 55.00 50.00 35.45 24.08

70.00 25.00 50.00 38.82 12.64

70.00 85.00 50.00 42.06 17.41

70.00 55.00 0.00 35.24 34.58

70.00 55.00 100.00 15.61 12.01

20.00 25.00 0.00 22.30 59.56

20.00 25.00 100.00 8.02 15.57

20.00 85.00 0.00 34.81 42.49

20.00 85.00 100.00 18.71 50.93

120.00 25.00 0.00 31.44 40.82

120.00 25.00 100.00 15.33 8.79

120.00 85.00 0.00 34.96 45.61

120.00 85.00 100.00 32.70 21.89

70.00 55.00 50.00 41.03 14.62

Table 2. Natural and coded values of the extraction variables [4].

Natural variables Coded value

t (min) T (◦

C) S (%)

20.0 25.0 0.0 −1.68

40.3 37.2 20.0 −1.00

70 55 50.0 0.00

99.7 72.8 80.0 1.00

120 85 100.0 1.68](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-20-320.jpg)

![8 L. A. Lima et al.

Fig. 2. Flowchart of traditional RSM modeling approach for optimal design.

where, for i = 0, ..., n and j = 1, ..., n, bi stand for the linear coefficients; bij

correspond to the interaction coefficients while bii are the quadratic coefficients;

and, finally, Xi are the independent variables, associated to t, T and S, being n

the total number of variables.

In the previous study, the traditional RSM, Eq. 1 represents coherently the

behaviour of the extraction process of the target compounds from chestnut flow-

ers [4]. In order to compare the optimization methods and to avoid data conflict,

the estimation of the cost function was done based on a multivariate regression

model.

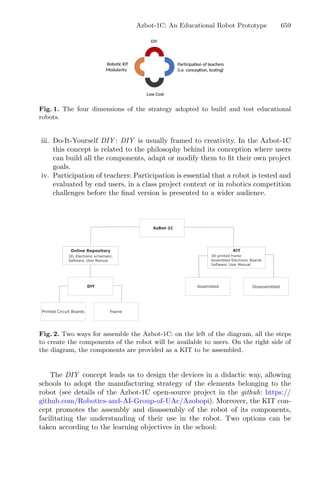

4.2 Dynamic RSM

For the proposed optimization method, briefly described in the flowchart shown

in Fig. 3, the structure of the design of the experience was maintained, as well

as the imposed restrictions on the responses and variables to elude awkward

solutions.

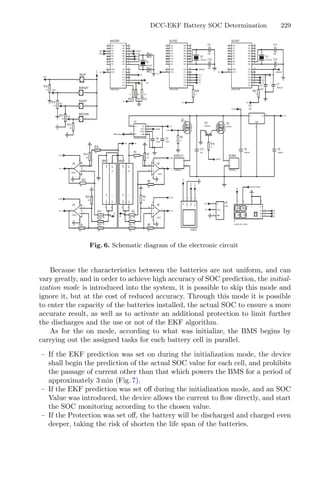

Fig. 3. Flowchart of dynamic RSM integrating genetic algorithm and cluster analysis

to the process.

The dynamic RSM method was build in MATLAB R

using a programming

code developed by the authors coupled with pre-existing functions from the

statistical and optimization toolboxes of the software. The algorithm starts by

generating a set of 15 random combinations between the levels of combinatorial

analysis. From this initial experimental data, a multivariate regression model is

calculated, being this model the objective function of the problem. Thereafter,

a built-in GA-based solver was used to solve the optimization problem. The

optimal combination is identified and it is used to define the objective function.

The process stops when no new optimal solution is identified.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-21-320.jpg)

![Dynamic RSM Combined with GA to Optimize Extraction Process Problem 9

Considering the stochastic nature of this case study, clustering analysis is

used to identify the best candidate optimal solution. In order to handle the

variability of the achieved optimal solution, the bootstrap method is used to

estimate the confidence interval at 95%.

5 Numerical Results

The study using the traditional RSM returned the following optimal conditions

for maximum yield: 120.0 min, 85.0 ◦

C, and 44.5% of ethanol in the solvent, pro-

ducing 48.87% of dry extract. For total phenolic content, the optimal conditions

were: 20.0 min, 25.0 ◦

C and S = 0.0% of ethanol in the solvent, producing 55.37

mg/g of dry extract. These data are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3. Optimal responses and respective conditions using traditional and dynamic

RSM based on confidence intervals at 95%.

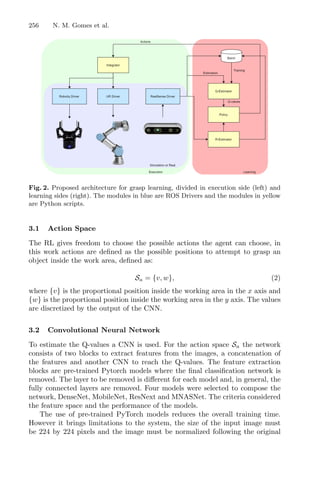

Method t (min) T (◦

C) S (%) Response

Extraction yield (%) Traditional RSM 120.0 ± 12.4 85.0 ± 6.7 44.5 ± 9.7 48.87

Dynamic RSM 118.5 ± 1.4 84.07 ± 0.9 46.1 ± 0.85 45.87

Total phenolics (Phe) Traditional RSM 20.0 ± 3.7 25.0 ± 5.7 0.0 ± 8.7 55.37

Dynamic RSM 20.4 ± 1.5 25.1 ± 1.97 0.05 ± 0.05 55.64

For the implementation of dynamic RSM in this case study, 100 runs were

carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of the method. For the yield, the esti-

mated optimal conditions were: 118.5 min, 84.1 ◦

C, and 46.1% of ethanol in the

solvent, producing 45.87% of dry extract. In this case, the obtained optimal con-

ditions for time and temperature were in accordance with approximately 80% of

the tests.

For the total phenolic content, the optimal conditions were: 20.4 min, 25.1

◦

C, and 0.05% of ethanol in the solvent, producing 55.64 mg/g of dry extract.

The results were very similar to the previous report with the same data [4].

The clustering analysis for each response variable was performed considering

the means (Figs. 4a and 5a) and the medoids (Figs. 4b and 5b) for the output

population (optimal responses). The bootstrap analysis makes the inference con-

cerning the results achieved and are represented graphically in terms of mean in

Figs. 4c and 5c, and in terms of medoids in Figs. 4d and 5d.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-22-320.jpg)

![12 L. A. Lima et al.

Fig. 7. Histograms of the extraction data (extraction yield) and the bootstrap means,

respectively.

Fig. 8. Histograms of the extraction data (total phenolic content) and the bootstrap

means, respectively.

The results obtained in this work are satisfactory since they were analogous

for both methods, although dynamic RSM took 15 to 18 experimental points

to find the optimal coordinates. Some authors use the design of experiments

involving traditional RSM containing 20 different combinations, including the

repetition of centroid [4]. However, in studies involving recent data or the absence

of complementary data, evaluations about the influence of parameters and range

are essential to obtain consistent results, making it necessary to make about 30

experimental points for optimization. Considering these cases, the dynamic RSM

method proposes a different, competitive, and economical approach, in which

fewer points are evaluated to obtain the maximum response.

Genetic algorithms have been providing their efficiency in the search for

optimal solutions in a wide variety of problems, given that they do not have

some limitations found in traditional search methodologies, such as the require-

ment of the derivative function, for example [9]. GA is attractive to identify the

global solution of the problem. Considering the stochastic problem presented in

this work, the association of genetic algorithm with the k-methods as clustering

algorithm obtained satisfactory results. This solution can be used for problems

involving small-scale data since GA manages to gather the best data for opti-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-25-320.jpg)

![Dynamic RSM Combined with GA to Optimize Extraction Process Problem 13

mization through its evolutionary method, while k-means or k-medoids make the

grouping of optimum points.

In addition to clustering analysis, bootstrapping was also applied, in which

the sample distribution of the statistic of interest is simulated through the use

of many resamples with replacement of the original sample, thus enabling to

make the statistical inference. Bootstrapping was used to calculate the confidence

intervals to obtain unbiased estimates from the proposed method. In this case,

the confidence interval was calculated at the 95% level (two-tailed), since the

same percentage was adopted by Caleja et al. (2019). It was observed that the

Dynamic RSM approach also enables the estimation of confidence intervals with

less margin of error than the Traditional RSM approach, conducting to define

more precisely the optimum conditions for the experiment.

6 Conclusion and Future Work

For the presented case study, applying dynamic RSM using Genetic Algorithm

coupled with clustering analysis returned positive results, in accordance with

previous published data [4]. Both methods seem attractive for the resolution

of this particular case concerning the optimization of the extraction of target

compounds from plant matrices. Therefore, the smaller number of experiments

required for dynamic RSM can be an interesting approach for future studies.

In brief, a smaller set of points was obtained that represent the best domain

of optimization, thus eliminating the need for a large number of costly labora-

tory experiments. The next steps involve the improvement of the dynamic RSM

algorithm and the application of the proposed method in other areas of study.

Acknowledgments. The authors are grateful to FCT for financial support through

national funds FCT/MCTES UIDB/00690/2020 to CIMO and UIDB/05757/2020.

M. Carocho also thanks FCT through the individual scientific employment program-

contract (CEECIND/00831/2018).

References

1. Beasley, D., Bull, D.R., Martin, R.R.: An overview of genetic algorithms: Part 1,

fundamentals. Univ. Comput. 2(15), 1–16 (1993)

2. Box, G.E.P., Behnken, D.W.: Simplex-sum designs: a class of second order rotatable

designs derivable from those of first order. Ann. Math. Stat. 31(4), 838–864 (1960)

3. Box, G.E.P., Wilson, K.B.: On the experimental attainment of optimum conditions.

J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.) 13(1), 1–38 (1951)

4. Caleja C., Barros L., Prieto M. A., Bento A., Oliveira M.B.P., Ferreira, I.C.F.R.:

Development of a natural preservative obtained from male chestnut flowers: opti-

mization of a heat-assisted extraction technique. In: Food and Function, vol. 10,

pp. 1352–1363 (2019)

5. Efron, B., Tibshirani, R.J.: An introduction to the Bootstrap, 1st edn. Wiley, New

York (1994)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-26-320.jpg)

![Towards a High-Performance

Implementation of the MCSFilter

Optimization Algorithm

Leonardo Araújo1,2

, Maria F. Pacheco2

, José Rufino2

,

and Florbela P. Fernandes2(B)

1

Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná,

Campus de Ponta Grossa, Ponta Grossa 84017-220, Brazil

2

Research Centre in Digitalization and Intelligent Robotics (CeDRI),

Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, 5300-252 Bragança, Portugal

a46677@alunos.ipb.pt, {pacheco,rufino,fflor}@ipb.pt

Abstract. Multistart Coordinate Search Filter (MCSFilter) is an opti-

mization method suitable to find all minimizers – both local and global –

of a non convex problem, with simple bounds or more generic constraints.

Like many other optimization algorithms, it may be used in industrial

contexts, where execution time may be critical in order to keep a pro-

duction process within safe and expected bounds. MCSFilter was first

implemented in MATLAB and later in Java (which introduced a signif-

icant performance gain). In this work, a comparison is made between

these two implementations and a novel one in C that aims at further

performance improvements. For the comparison, the problems addressed

are bound constraint, with small dimension (between 2 and 10) and mul-

tiple local and global solutions. It is possible to conclude that the average

time execution for each problem is considerable smaller when using the

Java and C implementations, and that the current C implementation,

though not yet fully optimized, already exhibits a significant speedup.

Keywords: Optimization · MCSFilter method · MatLab · C · Java ·

Performance

1 Introduction

The set of techniques and principals for solving quantitative problems known as

optimization has become increasingly important in a broad range of applications

in areas of research as diverse as engineering, biology, economics, statistics or

physics. The application of the techniques and laws of optimization in these

(and other) areas, not only provides resources to describe and solve the specific

problems that appear within the framework of each area but it also provides the

opportunity for new advances and achievements in optimization theory and its

techniques [1,2,6,7].

c

Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

A. I. Pereira et al. (Eds.): OL2A 2021, CCIS 1488, pp. 15–30, 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91885-9_2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-28-320.jpg)

![16 L. Araújo et al.

In order to apply optimization techniques, problems can be formulated in

terms of an objective function that is to be maximized or minimized, a set of

variables and a set of constraints (restrictions on the values that the variables can

assume). The structure of the these three items – objective function, variables

and constraints –, determines different subfields of optimization theory: linear,

integer, stochastic, etc.; within each of these subfields, several lines of research

can be pursued. The size and complexity of optimization problems that can be

dealt with has increased enormously with the improvement of the overall per-

formance of computers. As such, advances in optimization techniques have been

following progresses in computer science as well as in combinatorics, operations

research, control theory, approximation theory, routing in telecommunication

networks, image reconstruction and facility location, among other areas [14].

The need to keep up with the challenges of our rapidly changing society and

its digitalization means a continuing need to increase innovation and productiv-

ity and improve the performance of the industry sector, and places very high

expectations for the progress and adaptation of sophisticated optimization tech-

niques that are applied in the industrial context. Many of those problems can be

modelled as nonlinear programming problems [10–12] or mixed integer nonlinear

programming problems [5,8]. The urgency to quickly output solutions to difficult

multivariable problems, leads to an increasing need to develop robust and fast

optimization algorithms. Considering that, for many problems, reliable informa-

tion about the derivative of the objective function is unavailable, it is important

to use a method that allows to solve the problem without this information.

Algorithms that do not use derivatives are called derivative-free. The MCS-

Filter method is such a method, being able to deal with discontinuous or non-

differentiable functions that often appear in many applications. It is also a multi-

local method, meaning that it finds all the minimizers, both local and global, and

exhibits good results [9,10]. Moreover, a Java implementation was already used

to solve processes engineering problems [4]. Considering that, from an industrial

point of view, execution time is of utmost importance, a novel C reimplementa-

tion, aimed at increased performance, is currently under way, having reached a

stage at which it is already able to solve a broad set of problems with measur-

able performance gains over the previous Java version. This paper presents the

results of a preliminary evaluation of the new C implementation of the MCSFilter

method, against the previously developed versions (in MATLAB and Java).

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2, the MCSFilter algo-

rithm is briefly described; in Sect. 3 the set of problems that are used to compare

the three implementations and the corresponding results are presented and ana-

lyzed. Finally, in Sect. 4, conclusions and future work are addressed.

2 The Multistart Coordinate Search Filter Method

The MCSFilter algorithm was initially developed in [10], with the aim of finding

multiple solutions of nonconvex and nonlinear constrained optimization problems

of the following type:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-29-320.jpg)

![Towards a High-Performance Implementation of the MCSFilter 17

min f(x)

subject to gj(x) ≤ 0, j = 1, ..., m

li ≤ xi ≤ ui, i = 1, ..., n

(1)

where f is the objective function, gj(x), j = 1, ..., m are the constraint functions

and at least one of the functions f, gj : Rn

−→ R is nonlinear; also, l and u are

the bounds and Ω = {x ∈ Rn

: g(x) ≤ 0 , l ≤ x ≤ u} is the feasible region.

This method has two main different parts: i) the multistart part, related with

the exploration feature of the method, and ii) the coordinate search filter local

search, related with the exploitation of promising regions.

The MCSFilter method does not require any information about the deriva-

tives and is able to obtain all the solutions, both local and global, of a given non-

convex optimization problem. This is an important asset of the method since,

in industry problems, it is often not possible to know the derivative functions;

moreover, a large number of real-life problems are nonlinear and nonconvex.

As already stated, the MCSFilter algorithm relies on a multistart strategy

and a local search repeatedly called inside the multistart. Briefly, the multistart

strategy is a stochastic algorithm that applies more than once a local search to

sample points aiming to converge to all the minimizers, local and global, of a

multimodal problem. When the local search is repeatedly applied, some of the

minimizers can be reached more than once. This leads to a waste of time since

these minimizers have already been determined. To avoid these situations, a

clustering technique based on computing the regions of attraction of previously

identified minimizers is used. Thus, if the initial point belongs to the region of

attraction of a previously detected minimizer, the local search procedure may

not be performed, since it would converge to this known minimizer.

Figure 1 illustrates the influence of the regions of attraction. The red/magenta

lines between the initial approximation and the minimizer represent a local

search that has been performed; the red line represents the first local search that

converged to a given minimizer; the white dashed line between the two points

represents a discarded local search, using the regions of attraction. Therefore,

this representation intends to show the regions of attraction of each minimizer

and the corresponding points around each one. These regions are dynamic in the

sense that they may change every time a new initial point is used [3].

The local search uses a derivative-free strategy that consists of a coordinate

search combined with a filter methodology in order to generate a sequence of

approximate solutions that improve either the constraint violation or the objec-

tive function relatively to the previous approximation; this strategy is called

Coordinate Search Filter algorithm (CSFilter). In this way, the initial problem

is previously rewritten as a bi-objective problem (2):

min (θ(x), f(x))

x ∈ Ω

(2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-30-320.jpg)

![18 L. Araújo et al.

3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Fig. 1. Illustration of the multistart strategy with regions of attraction [3].

aiming to minimize, simultaneously, the objective function f(x) and the non-

negative continuous aggregate constraint violation function θ(x) defined in (3):

θ(x) = g(x)+2

+ (l − x)+2

+ (x − u)+2

(3)

where v+ = max{0, v}. For more details about this method see [9,10].

Algorithm 1 displays the steps of the MSCFilter method. The stopping condi-

tion of CSFilter is related with the step size α of the method (see condition (4)):

α αmin (4)

with αmin 1 and close to zero.

The main steps of the MCSFilter algorithm for finding global (as well as

local) solutions to problem (1) are shown in Algorithm 2.

The stopping condition of the MCSFilter algorithm is related to the number

of minimizers found and to the number of local searches that were applied in

the multistart strategy. Considering nl as the number of local searches used

and nm as the number of minimizers obtained, then Pmin =

nm(nm + 1)

nl(nl − 1)

. The

MCSFilter algorithm stops when condition (5) is reached:

Pmin (5)

where 1.

In this preliminary work, the main goal is to compare the performance

of MCSFilter when bound constraint problems are addressed, using different](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-31-320.jpg)

![Towards a High-Performance Implementation of the MCSFilter 19

Algorithm 1. CSFilter algorithm

Require: x and parameter values, αmin; set x̃ = x, xinf

F = x, z = x̃;

1: Initialize the filter; Set α = min{1, 0.05

n

i=1 ui−li

n

};

2: repeat

3: Compute the trial approximations zi

a = x̃ + αei, for all ei ∈ D⊕;

4: repeat

5: Check acceptability of trial points zi

a;

6: if there are some zi

a acceptable by the filter then

7: Update the filter;

8: Choose zbest

a ; set z = x̃, x̃ = zbest

a ; update xinf

F if appropriate;

9: else

10: Compute the trial approximations zi

a = xinf

F + αei, for all ei ∈ D⊕;

11: Check acceptability of trial points zi

a;

12: if there are some zi

a acceptable by the filter then

13: Update the filter;

14: Choose zbest

a ; Set z = x̃, x̃ = zbest

a ; update xinf

F if appropriate;

15: else

16: Set α = α/2;

17: end if

18: end if

19: until new trial zbest

a is acceptable

20: until α αmin

implementations of the algorithm: the original implementation in MATLAB [10],

a follow up implementation in Java (already used to solve problems from the

Chemical Engineering area [3,4,13]), and a new implementation in C (evaluated

for the first time in this paper).

3 Computational Results

In order to compare the performance of the three implementations of the MCS-

Filter optimization algorithm, a set of problems was chosen. The definition of

each problem (a total of 15 bound constraint problems) is given below, along

with the experimental conditions under which they were evaluated, as well as

the obtained results (both numerical and performance-related).

3.1 Benchmark Problems

The collection of problems was taken from [9] (and the references therein) and

all the fifteen problems in study are listed below. The problems were chosen in

such a way that different characteristics were addressed: they are multimodal

problems with more than one minimizer (actually, the number of minimizers

varies from 2 to 1024); they can have just one global minimizer or more than

one global minimizer; the dimension of the problems varies between 2 and 10.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-32-320.jpg)

![20 L. Araújo et al.

Algorithm 2. MCSFilter algorithm

Require: Parameter values; set M∗

= ∅, k = 1, t = 1;

1: Randomly generate x ∈ [l, u]; compute Bmin = mini=1,...,n{ui − li};

2: Compute m1 = CSFilter(x), R1 = x − m1; set r1 = 1, M∗

= M∗

∪ m1;

3: while the stopping rule is not satisfied do

4: Randomly generate x ∈ [l, u];

5: Set o = arg minj=1,...,k dj ≡ x − mj;

6: if do Ro then

7: if the direction from x to yo is ascent then

8: Set prob = 1;

9: else

10: Compute prob = φ( do

Ro

, ro);

11: end if

12: else

13: Set prob = 1;

14: end if

15: if ζ‡

prob then

16: Compute m = CSFilter(x); set t = t + 1;

17: if m − mj γ∗

Bmin, for all j = 1, . . . , k then

18: Set k = k + 1, mk = m, rk = 1, M∗

= M∗

∪ mk; compute Rk = x − mk;

19: else

20: Set Rl = max{Rl, x − ml}; rl = rl + 1;

21: end if

22: else

23: Set Ro = max{Ro, x − mo}; ro = ro + 1;

24: end if

25: end while

– Problem (P1)

min f(x) ≡

x2 −

5.1

4π2

x2

1 +

5

π

x1 − 6

2

+ 10

1 −

1

8π

cos(x1) + 10

s.t. −5 ≤ x1 ≤ 10, 0 ≤ x2 ≤ 15

• known global minimum f∗

= 0.39789.

– Problem (P2)

min f(x) ≡

4 − 2.1x2

1 +

x4

1

3

x2

1 + x1x2 − 4(1 − x2

2)x2

2

s.t. −2 ≤ xi ≤ 2, i = 1, 2

• known global minimum: f∗

= −1.03160.

– Problem (P3)

min f(x) ≡

n

i=1

sin(xi) + sin

2xi

3

s.t. 3 ≤ xi ≤ 13, i = 1, 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-33-320.jpg)

![32 M.-A. Dahito et al.

minimize

x∈X

f(x), (1)

where X is a bounded domain of either Rn

or Rc

× Zi

with c and i respectively

the number of continuous and integer variables. n = c+i is the dimension of the

problem and f is a blackbox function. Heuristic and non-heuristic techniques

can tackle this kind of problems. Among the main approaches used in DFO

are direct local search methods. The latter are iterative methods that, at each

iteration, evaluate a set of points in a certain radius that can be increased if a

better solution is found or decreased if the incumbent remains the best point at

the current iteration.

The Mesh Adaptive Direct Search (MADS) [1,4,5] is a famous direct local

search method used in DFO and BBO that is an extension of the Generalized

Pattern Search (GPS) introduced in [28]. MADS evolves on a mesh by first doing

a global exploration called the search phase and then, if a better solution than

the current iterate is not found, a local poll is performed. The points evaluated

in the poll are defined by a finite set of poll directions that is updated at each

iteration. The algorithm is derived in several instantiations available in the Non-

linear Optimization with the MADS algorithm (NOMAD) software [7,19] and

its performance is evaluated in several papers. As examples, a broad compar-

ison of DFO optimizers is performed on 502 problems in [25] and NOMAD is

used in [24] with a DACE surrogate and compared with other local and global

surrogate-based approaches in the context of constrained blackbox optimization

on an automotive optimization problem and twenty two test problems.

Given the growing number of algorithms to deal with BBO problems, the

choice of the most adapted method for solving a specific problem still remains

complex. In order to help with this decision, some tools have been developed

to compare the performance of algorithms. In particular, data profiles [20] are

frequently used in DFO and BBO to benchmark algorithms: they show, given

some precision or target value, the fraction of problems solved by an algorithm

according to the number of function evaluations. There also exist suites of aca-

demic test problems: although the latter are treated as blackbox functions, they

are analytically known, which is an advantage to understand the behaviour of

an algorithm. There are also available industrial applications but they are rare.

Twenty two implementations of derivative-free algorithms for solving box-

constrained optimization problems are benchmarked in [25] and compared with

each other according to different criteria. They use a set of 502 problems that

are categorized according to their convexity (convex or nonconvex), smoothness

(smooth or non-smooth) and dimensions between 1 and 300. The algorithms

tested include local-search methods such as MADS through NOMAD version

3.3 and global-search methods such as the NEW Unconstrained Optimization

Algorithm (NEWUOA) [23] using trust regions and the Covariance Matrix Adap-

tation - Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) [16] which is an evolutionary algorithm.

Simulation optimization deals with problems where at least some of the objec-

tive or constraints come from stochastic simulations. A review of algorithms to

solve simulation optimization is presented in [2], among which the NOMAD

software. However, this paper does not compare them due to a lack of standard

comparison tools and large-enough testbeds in this optimization branch.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-45-320.jpg)

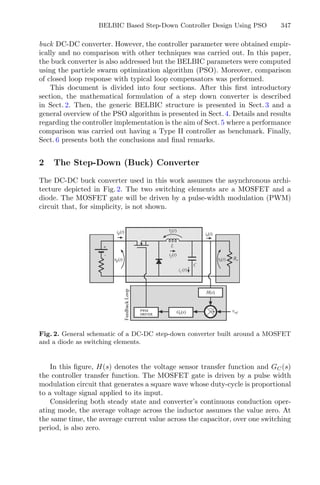

![ORTHOMADS on Continuous and Mixed-Integer Optimization Problems 33

In [3], the MADS algorithm is used to optimize the treatment process of

spent potliners in the production of aluminum. The problem is formalized as

a 7–dimensional non-linear blackbox problem with 4 inequality constraints. In

particular, three strategies are compared using absolute displacements, relative

displacements and the latter with a global Latin hypercube sampling search.

They show that the use of scaling is particularly beneficial on the considered

chemical application.

The instantiation ORTHOMADS is introduced in Ref. [1] and consists in using

orthogonal directions in the poll step of MADS. It is compared to the initial

LTMADS, where the poll directions are generated from a random lower trian-

gular matrix, and to GPS algorithm on 45 problems from the literature. They

show that MADS outperforms GPS and that the instantiation ORTHOMADS

competes with LTMADS and has the advantage that its poll directions cover

better the variable space.

The ORTHOMADS algorithm, which is the default MADS instantiation used

in NOMAD, presents variants in the poll directions of the method. To our knowl-

edge, the performance of these different variants has not been discussed in the

literature. The purpose of this paper is to explore this aspect by performing

experiments with the ORTHOMADS variants. This work is part of a project

conducted with the automotive group Stellantis to develop new approaches for

solving their blackbox optimization problems. Our contributions are first the

evaluations of the ORTHOMADS variants on continuous and mixed-integer opti-

mization problems. Besides, the contribution of the search phase is studied and

shows a general deterioration of the performance when the search is turned off.

The effect however decreases with increasing dimension. Two from the best vari-

ants of ORTHOMADS are identified on each of the used testbeds and their perfor-

mance is compared with other algorithms including heuristic and non-heuristic

techniques. Our experiments exhibit particular variants of ORTHOMADS per-

forming best depending on problems features. Plots for analyses are available at

the following link: https://github.com/DahitoMA/ResultsOrthoMADS.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives an overview of the

MADS algorithm and its ORTHOMADS variants. In Sect. 3, the variants of

ORTHOMADS are evaluated on the bbob and bbob-mixint suites that con-

sist respectively of continuous and mixed-integer functions. Then, two from the

best variants of ORTHOMADS are compared with other algorithms in Sect. 4.

Finally, Sect. 5 discusses the results of the paper.

2 MADS and the Variants of ORTHOMADS

This section gives an overview of the MADS algorithm and explains the differ-

ences among the ORTHOMADS variants.

2.1 The MADS Algorithm

MADS is an iterative direct local search method used for DFO and BBO prob-

lems. The method relies on a mesh Mk updated at each iteration and determined](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-46-320.jpg)

![34 M.-A. Dahito et al.

by the current iterate xk, a mesh parameter size δk 0 and a matrix D whose

columns consist of p positive spanning directions. The mesh is defined as follows:

Mk := {xk + δkDy : y ∈ Np

}, (2)

where the columns of D form a positive spanning set {D1, D2, . . . , Dp} and N

stands for natural numbers.

The algorithm proceeds in two phases at each iteration: the search and the

poll. The search phase is optional and similar to a design of experiment: a finite

set of points Sk, stemming generally from a surrogate model prediction and a

Nelder-Mead (N-M) search [21], are evaluated anywhere on the mesh. If the

search fails at finding a better point, then a poll is performed. During the poll

phase, a finite set of points are evaluated on the mesh in the neighbourhood of

the incumbent. This neighbourhood is called the frame Fk and has a radius of

Δk 0 that is called the poll size parameter. The frame is defined as follows:

Fk := {x ∈ Mk : x − xk∞ ≤ Δkb}, (3)

where b = max{d∞, d ∈ D} and D ⊂ {D1, D2, . . . , Dp} is a finite set of poll

directions. The latter are such that their union over iterations grows dense on

the unit sphere.

The two size parameters are such that δk ≤ Δk and evolve after each itera-

tion: if a better solution is found, they are increased and otherwise decreased. As

the mesh size decreases more drastically than the poll size in case of an unsuc-

cessful iteration, the choice of points to evaluate during the poll becomes greater

with unsuccessful iteration. Usually, δk = min{Δk, Δ2

k}. The description of the

MADS algorithm is given in Algorithm 1 and inspired from [6].

Algorithm 1: Mesh Adaptive Direct Search (MADS)

Initialize k = 0, x0 ∈ Rn

, D ∈ Rn×p

, Δ0 0, τ ∈ (0, 1) ∩ Q, stop 0

1. Update δk = min{Δk, Δ2

k}

2. Search

If f(x) f(xk) for x ∈ Sk then xk+1 ← x, Δk+1 ← τ−1

Δk and go to 4

Else go to 3

3. Poll

Select Dk,Δk such that Pk := {xk + δkd : d ∈ Dk,Δk } ⊂ Fk

If f(x) f(xk) for x ∈ Pk then xk+1 ← x, Δk+1 ← τ−1

Δk and go to 4

Else xk+1 ← xk and Δk+1 ← τΔk

4. Termination

If Δk+1 ≥ stop then k ← k + 1 and go to 1

Else stop

2.2 ORTHOMADS Variants

MADS has two main instantiations called ORTHOMADS and LTMADS, the

latter being the first developed. Both variants are implemented in the NOMAD](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-47-320.jpg)

![ORTHOMADS on Continuous and Mixed-Integer Optimization Problems 35

software but as ORTHOMADS is to be preferred for its coverage property in

the variable space, it was used for the experiments of this paper with NOMAD

version 3.9.1.

The NOMAD implementation of ORTHOMADS provides 6 variants of the

algorithm according to the number of directions used in the poll or according to

the way that the last poll direction is computed. They are listed below.

ORTHO N + 1 NEG computes n + 1 directions among which n are orthogonal

and the (n + 1)th

direction is the opposite sum of the n first ones.

ORTHO N + 1 UNI computes n + 1 directions among which n are orthogonal

and the (n + 1)th

direction is generated from a uniform distribution.

ORTHO N + 1 QUAD computes n + 1 directions among which n are orthogonal

and the (n+1)th

direction is generated from the minimization of a local quadratic

model of the objective.

ORTHO 2N computes 2n directions that are orthogonal. More precisely each

direction is orthogonal to 2n−2 directions and collinear with the remaining one.

ORTHO 1 uses only one direction in the poll.

ORTHO 2 uses two opposite directions in the poll.

In the plots, the variants will respectively be denoted using Neg, Uni, Quad,

2N, 1 and 2.

3 Test of the Variants of ORTHOMADS

In this section, we try to identify potentially better direction types of

ORTHOMADS and investigate the contribution of the search phase.

3.1 The COCO Platform and the Used Testbeds

The COmparing Continuous Optimizers (COCO) platform [17] is a bench-

marking framework for blackbox optimization. In this respect, several suites

of standard test problems are provided and are declined in variants, also called

instances. The latter are obtained from transformations in variable and objective

space in order to make the functions less regular.

In particular, the bbob testbed [13] provides 24 continuous problems for

blackbox optimization, each of them available in 15 instances and in dimensions

2, 3, 5, 10, 20 and 40. The problems are categorized in five subgroups: separable

functions, functions with low or moderate conditioning, ill-conditioned functions,

multi-modal functions with global structure and multi-modal weakly structured

functions. All problems are known to have their global optima in [−5, 5]n

, where

n is the size of a problem.

The mixed-integer suite of problems bbob-mixint [29] derives the bbob and

bbob-largescale [30] problems by imposing integer constraints on some vari-

ables. It consists of the 24 functions of bbob available in 15 instances and in

dimensions 5, 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160.

COCO also provides various tools for algorithm comparison, notably Empir-

ical Cumulative Distribution Function (ECDF) plots (or data profiles) that are](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-48-320.jpg)

![ORTHOMADS on Continuous and Mixed-Integer Optimization Problems 39

ORTHO 2N. Besides, Neg reaches more targets on problems with low or moderate

conditioning. For these reasons, ORTHO N + 1 NEG was chosen for comparison with

other solvers. Besides, the mentioned slight advantage of ORTHO N + 1 QUAD over

ORTHO 2N, its equivalent or better performance on separable and ill-conditioned

functions compared with the latter variant, makes it a good second choice to

represent ORTHOMADS.

(a) 5D (b) 10D (c) 20D

Fig. 2. ECDF plots: the variants of ORTHOMADS with and without the search step

on the bbob-mixint problems. Results aggregated on all functions in dimensions 5, 10

and 20.

4 Comparison of ORTHOMADS with other solvers

The previous experiments showed the advantage of using the search step in

ORTHOMADS to speed up convergence. They also revealed the effectiveness of

some variants that are used here for comparisons with other algorithms on the

continuous and mixed-integer suites.

4.1 Compared Algorithms

Apart from ORTHOMADS, the other algorithms used for comparison on bbob

are first, three deterministic algorithms: the quasi-Newton Broyden-Fletcher-

Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) method [22], the quadratic model-based NEWUOA

and the adaptive N-M [14] that is a simplicial search. Stochastic methods are also

used among which a Random Search (RS) algorithm [10] and three population-

based algorithms: a surrogate-assisted CMA-ES, Differential Evolution (DE) [27]

and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [11,18].

In order to perform algorithm comparisons on bbob-mixint, data from four

stochastic methods were collected: RS, the mixed-integer variant of CMA-ES,

DE and the Tree-structured Parzen Estimator (TPE) [8] that is a stochastic

model-based technique.

BFGS is an iterative quasi-Newton linesearch method that uses approxima-

tions of the Hessian matrix of the objective. At iteration k, the search direc-

tion pk solves a linear system Bkpk = −∇f(xk), where xk is the iterate, f the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-52-320.jpg)

![40 M.-A. Dahito et al.

objective function and Bk ≈ ∇2

f(xk). The matrix Bk is then updated according

to a formula. In the context of BBO, the derivatives are approximated with finite

differences.

NEWUOA is the Powell’s model-based algorithm for DFO. It is a trust-region

method that uses sequential quadratic interpolation models to solve uncon-

strained derivative-free problems.

The N-M method is a heuristic DFO method that uses simplices. It begins

with a non degenerated simplex. The algorithm identifies the worst point among

the vertices of the simplex and tries to replace it by reflection, expansion or

contraction. If none of these geometric transformations of the worst point enables

to find a better point, a contraction preserving the best point is done. The

adaptive N-M method uses the N-M technique with adaptation of parameters

to the dimension, which is notably useful in high dimensions.

RS is a stochastic iterative method that performs a random selection of

candidates: at each iteration, a random point is sampled and the best between

this trial point and the incumbent is kept.

CMA-ES is a state-of-the art evolutionary algorithm used in DFO. Let

N(m, C) denote a normal distribution of mean m and covariance matrix C.

It can be represented by the ellipsoid x

C−1

x = 1. The main axes of the ellip-

soid are the eigenvectors of C and the square roots of their lengths correspond

to the associated eigenvalues. CMA-ES iteratively samples its populations from

multivariate normal distributions. The method uses updates of the covariance

matrices to learn a quadratic model of the objective.

DE is a meta-heuristic that creates a trial vector by combining the incumbent

with randomly chosen individuals from a population. The trial vector is then

sequentially filled with parameters from itself or the incumbent. Finally the best

vector between the incumbent and the created vector is chosen.

PSO is an archive-based evolutionary algorithm where candidate solutions

are called particles and the population is a swarm. The particles evolve according

to the global best solution encountered but also according to their local best

points.

TPE is an iterative model-based method for hyperparameter optimization.

It sequentially builds a probabilistic model from already evaluated hyperparam-

eters sets in order to suggest a new set of hyperparameters to evaluate on a score

function that is to be minimized.

4.2 Parameter Setting

To compare the considered best variants of ORTHOMADS with other methods,

the 15 instances of each function were used and the maximal function evaluation

budget was increased to 105

× n, with n being the dimension.

For the bbob problems, the data used for BFGS, DE and the adaptive N-M

method comes from the experiments of [31]. CMA-ES was tested in [15], the

data of NEWUOA is from [26], the one of PSO is from [12] and RS results

come from [9]. The comparison data of CMA-ES, DE, RS and TPE used on](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-53-320.jpg)

![ORTHOMADS on Continuous and Mixed-Integer Optimization Problems 41

the bbob-mixint suite comes from the experiments of [29]. All are accessi-

ble from the data archives of COCO with the cocopp.archives.bbob and

cocopp.archives.bbob mixint methods.

4.3 Results

Continuous Problems. Figures 3 and 4 show the ECDF plots comparing the

methods on the different function types and on all functions, respectively in

dimensions 5 and 20 on the continuous suite. Compared with BFGS, CMA-ES,

DE, the adaptive N-M method, NEWUOA, PSO and RS, ORTHOMADS often

performs in the average for medium and high dimensions. For small dimensions

2 and 3, it is however among the most competitive.

Considering the results aggregated on all functions and splitting them over all

targets according to the function evaluations, they can be divided in three parts.

The first one consists of very limited budgets (about 20 × n) where NEWUOA

competes with or outperforms the others. After that, BFGS becomes the best

for an average budget and CMA-ES outperforms the latter for high evaluation

budgets (above the order of 102

× n), as shown in Figs. 3f and 4f. The obtained

performance restricted to a low budget is an important feature relevant to many

applications for which each function evaluation may last hours or even days.

On multi-modal problems with adequate structure, there is a noticeable gap

between the performance of CMA-ES, which is the best algorithm on this kind of

problems, and the other algorithms as shown by Figs. 3d and 4d. ORTHOMADS

performs the best in the remaining methods and competes with CMA-ES for

low budgets. It is even the best method up to a budget of 103

× n in 2D and 3D

while it competes with CMA-ES in higher dimensions for budgets lower than

the order of 102

× n.

RS is often the worse algorithm to use on the considered problems.

Mixed-Integer Problems. Figures 5 and 6 show the ECDF plots comparing

the methods on the different function types and on all functions, respectively

in dimensions 5 and 20 on the mixed-integer suite. The comparisons of NEG

and QUAD with CMA-ES, DE, RS and TPE show an overall advantage of these

ORTHOMADS variants over the other methods. A gap is especially visible on

separable and ill-conditioned problems, respectively depicted in Figs. 5a and 6a

and Figs. 5c and 6c in dimensions 5 and 20, but also on moderately conditioned

problems as shown in Figs. 5b and 6b in 5D and 20D. On multi-modal prob-

lems with global structure, ORTHOMADS is to prefer only in small dimensions:

from 10D its performance highly deteriorates and CMA-ES and DE seem to be

better choices. On multi-modal weakly structured functions, the advantages of

ORTHOMADS compared to the others emerge when the dimension increases.

Besides, although the performance of all algorithms decreases with increasing

dimensions, ORTHOMADS seems less sensitive to that. For instance, for a budget

of 102

× n, ORTHOMADS reaches 15% more targets than CMA-ES and TPE

that are the second best algorithms until this budget, and in dimension 20 this

gap increases to 18% for CMA-ES and 25% for TPE.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-54-320.jpg)

![A Look-Ahead Based Meta-heuristics

for Optimizing Continuous Optimization

Problems

Thomas Nordli and Noureddine Bouhmala(B)

University of South-Eastern Norway, Kongsberg, Norway

{thomas.nordli,noureddine.bouhmala}@usn.no

http://www.usn.no

Abstract. In this paper, the famous kernighan-Lin algorithm is adjusted

and embedded into the simulated annealing algorithm and the genetic

algorithm for continuous optimization problems. The performance of the

different algorithms are evaluated using a set of well known optimization

test functions.

Keywords: Continuous optimization problems · Simulated annealing ·

Genetic algorithm · Local search

1 Introduction

Several types of meta-heuristics methods have been designed for solving contin-

uous optimization problems. Examples include genetic algorithms [8,9] artificial

immune systems [7], and taboo search [5]. Meta-heuristics can be divided into

two different classes. The first class refers to single-solution search algorithms.

A notable example that belongs to this class is the popular simulated annealing

algorithm (SA) [12], which is a random search that avoids getting stuck in local

minima. In addition to solutions corresponding to an improvement in objective

function value, SA also accepts those corresponding to a worse objective function

value using a probabilistic acceptance strategy.

The second class of algorithms refer to population based algorithms. Algo-

rithms of this class applies the principle of survival of the fittest to a population

of potential solutions, iteratively improving the population. During each genera-

tion, pairs of solutions called individuals are generated to breed a new generation

using operators borrowed from natural genetics. This process is repeated until a

stopping criteria has been reached. Genetic algorithm is one among many that

belongs to this class. The following papers [1,2,6] provide a review of the lit-

erature covering the use of evolutionary algorithms for solving continuous opti-

mization problems. In spite of the advantages that meta-heuristics offer, they

still suffer from the phenomenon of premature convergence.

c

Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

A. I. Pereira et al. (Eds.): OL2A 2021, CCIS 1488, pp. 48–55, 2021.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91885-9_4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-61-320.jpg)

![A Look-Ahead Based Meta-heuristics for Continuous Optimization 49

Recently, several studies combined meta-heuristics with local search meth-

ods, resulting in more efficient methods with relatively faster convergence, com-

pared to pure meta-heuristics. Such hybrid approaches offer a balance between

diversification—to cover more regions of a search space, and intensification – to

find better solutions within those regions. The reader might refer to [3,14] for

further reading on hybrid optimization methods.

This paper introduces a hybridization of genetic algorithm and simulated

annealing with the variable depth search (VDS) Kernighan-Lin algorithm (KL)

(which was firstly presented for graph partitioning problem in [11]). Compared

to simple local search methods, KL allows making steps that worsens the quality

of the solution on a short term, as long as the result gives an improvement in a

longer run.

In this work, the search for one favorable move in SA, and one two-point

cross-over in GA, are replaced by a search for a favorable sequence of moves in

SA and a series of two-point crossovers using the objective function to guide

the search.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the com-

bined simulated annealing and KL heuristic, while Sect. 3 explains the hybridiza-

tion of KL with the genetic algorithm. Section 4 lists the functions used in the

benchmark while Section 5 shows the experimental results. Finally, Sect. 6 con-

cludes the paper with some future work.

2 Combining Simulated Annealing with Local Search

Previously, SA in combination with KL, was applied for the Max-SAT problem in

[4]. SA iteratively improves a solution by making random perturbations (moves)

to the current solution—exploring the neighborhood in the space of possible

solutions. It uses a parameter called temperature to control the decision whether

to accept bad moves or not. A bad move is a solution that decreases the value

of the objective function.

The algorithm starts of with a high temperature, when that almost all

moves are accepted. For each iteration, the temperature decreases, the algorithm

becomes selective, giving higher preference for better solutions.

Assuming an objective function f is to be maximized. The algorithm starts

computing the initial temperature T, using a procedure similar to the one

described in [12]. The temperature is computed such that the probability of

accepting a bad move is approximately equal to a given probability of acceptance

Pr. First, a low value of is chosen as the initial temperature. This temperature

is used during a number of moves.

If the ratio of accepted bad moves is less than Pr, the temperature is multi-

plied by two. This continues until the observed acceptance ratio exceeds Pr. A

random starting solution is generated and its value is calculated. An iteration

of the algorithm starts by performing a series of so-called KL perturbations or

moves to the solution Sold leading to a new solution Si

new where i denotes the

number of consecutive moves. The change in the objective function called gain is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-62-320.jpg)

![50 T. Nordli and N. Bouhmala

computed for each move. The goal of KL perturbation is to generate a sequence

of objective function scores together with their corresponding moves. KL is sup-

posed to reach convergence if the function scores of five consecutive moves are

bad moves. The subset of moves having the best cumulative score BCSk

(SA+KL)

is identified. The identification of this subset is equivalent to choosing k so that

BCSk

(SA+KL) in Eq. 1 is maximum,

BCSk

(SA+KL) =

k

i=1

gain(Si

new) (1)

where i represents the ith

move performed, k the number of a moves, and

gain(Si

new) = f(Si

new) − f(Si−1

new) denotes the resultant change of the objective

function when ith

move has been performed. If BCSk

(SA+KL) 0, the solution

is updated by taking all the perturbations up to the index k and the best solu-

tion is always recorded. If (BCSk

SA+KL ≤ 0), the simulated acceptance test is

restricted to only the resultant change of the first perturbation. A number from

the interval (0,1) is drawn by a random number generator. The move is accepted

ff the drawn number is less than exp−δf/T

. The process of proposing a series of

perturbations and selecting the best subset of moves is repeated for a number of

iterations before the temperature is updated. A temperature reduction function

is used to lower the temperature. The updating of the temperature is done using

a geometric cooling, as shown in Eq. 2

Tnew = α × Told, where α = 0.9. (2)

3 Combining Genetic Algorithm with Local Search

Genetic Algorithm (GA) belong to the group of evolutionary algorithms. It works

on a set of solutions called a population. Each of these members, called chro-

mosomes or individuals, is given a score (fitness), allowing the assessing of its

quality. The individuals of the initial population are in most cases generated

randomly. A reproduction operator selects individuals as parents, and generates

off-springs by combining information from the parent chromosomes. The new

population might be subject to a mutation operator introducing diversity to the

population. A selection scheme is then used to update the population—resulting

in a new generation. This is repeated until the convergence is reached—giving

an optimal or near optimal solution.

The simple GA as described in [8] is used here. It starts by generating an ini-

tial population represented by floating point numbers. Solutions are temporary

converted to integers when bit manipulation is needed, and resulting integers are

converted back to floating point representation for storage. A roulette function

is used for selections. The implementation and based on the one described in

section IV of [10], where more details can be found.

The purpose of KL-Crossover is to perform the crossover operator a number

of times generating a sequence of fitness function scores together with their cor-

responding crossover. Thereafter, the subset of consecutive crossovers having the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-63-320.jpg)

![A Look-Ahead Based Meta-heuristics for Continuous Optimization 51

best cumulative score BCSk

(GA−KL) is determined. The identification of this sub-

set is the same as described in SA-KL. GA-KL chooses k so that BCSk

(GA+KL)

in Eq. 4 is maximum, where CRi

represents the ith

crossover performed on two

individuals, Il and Im, k the number of allowed crossovers, and gain(Il, Im)CRi

denotes the resulting change in the fitness function when the ith

crossover CRi

has been performed calculated shown in Eq. 3.

gain(Il, Im)CRi = f(Il, Im)CRi − f(Il, Im)CRi−1 , (3)

where CR0

refers to the chosen pair of parents before applying the cross-

over operator. KL-crossover is supposed to reach convergence if the gain of five

consecutive cross-overs is negative. Finally, the individuals that are best fit are

allowed to move to the next generation while the other half is removed and a

new round is performed.

BCSk

(GA+KL) = Max

k

i=1

gain(Individuall, Individualm)CRi

. (4)

4 Benchmark Functions and Parameter Setting

The stopping criterion for all four algorithms (SA, SA-Look-Ahead, GA, GA-

Look-Ahead) is supposed to be reached if the best solution has not been improved

during 100 consecutive iterations for (SA, SA-Look-Ahead) or 10 generations for

(GA, GA-Look-Ahead). The starting temperature for (SA, Look-Ahead-SA) is

set to 0.8 (i.e., a bad move has a probability of 80% for being accepted). In the

inner loop of (SA, Look-Ahead-SA), the equilibrium is reached if the number of

accepted moves is less than 10%.

The ten following benchmark functions were retrieved from [13] and tested.

1: Drop Wave f(x, y) = −

1+cos(12

x2+y2)

1

2

(x2+y2)+2

2: Griewangk f(x) = 1

4000

n

i=1 −

n

i=1 cos(

xi

√

i

) + 1

3: Levy Function sin2(3πx) + (x − 1)2[1 + sin2(3πy)] + (y − 1)2[1 + sin2(2πy)]

4: Rastrigin f(x) = 10n +

n

i=1(x2

i − 10 cos 2πxi)

5: Sphere Function f(x) =

n

i=1 x2

i

6: Weighted Sphere Function f(x, y) = x2 + 2y2

7: Sum of different power functions f(x) =

n

i=1 |xi|i+1

8: Rotated hyper-ellipsoid f(x) =

n

i=1

i

j=1 x2

j

9: Rosenbrock’s valley f(x) =

n−1

i=1

[100(xi+1 − x2

i )2 + (1 − xi)2]

10: Three Hump Camel Function f(x, y) = x2 − 1.05x4 + x6

6

+ xy + y2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-64-320.jpg)

![Inverse Optimization for Warehouse Management 57

the more complex an optimization model is needed, which can make it very

challenging to find a satisfactory solution in reasonable time, whether by generic

optimization algorithms or case-specific customized heuristics. Moreover, the

dynamic nature of business often necessitates regular updates to any decision

support tools as business processes and objectives change.

To make it easier to develop industrial decision support tools, one potential

approach is to apply machine learning methods to data from existing planning

processes. The data on actual decisions can be assumed to indicate the pref-

erences of competent decision makers, who have considered the effects of all

relevant factors and operational constraints in each decision. If a general control

policy can be derived from example decisions, the policy can then be replicated

in an automated decision support tool to reduce the manual planning effort,

or even completely automate the planning process. There would be no need to

explicitly model the preferences of the operational management at a particular

company. Ideally the control policy learned from data is generalisable to new

planning situations that differ from the training data, and can also be explained

in an understandable manner to business managers. In addition to implement-

ing tools for operational management, machine learning of management policies

could also be a useful tool when developing business simulation models for strate-

gic decision support.

The goal of this case study was to investigate whether inverse optimization

would be a suitable machine learning method to automate warehouse manage-

ment on the basis of demonstration data. In the study, inverse optimization

was applied to the problem of storage location assignment, i.e. where to place

incoming packages in a large warehouse. A mixed-integer model and a column

generation procedure were formulated for dynamic class-based storage location

assignment, with explicit consideration for the arrival and departure points of

goods, and possible congestion in warehouse stocking and picking activities.

The main contributions of the study are 1) combining the inverse optimiza-

tion approach of Ahuja and Orlin [1] with a cutting plane algorithm in the

first known application of inverse optimization to a storage location assignment

problem, and 2) computational experiments on applying the estimated objective

function in a practical rolling horizon procedure with real-world data.

2 Related Work

A large variety of analytical approaches have been published for warehouse

design and management [6,8,12,21]. Hausman et al. [10] presented an early

analysis of basic storage location assignment methods including random stor-

age, turnover-based storage in which highest-turnover products are assigned to

locations with the shortest transport distance, and class-based storage in which

products are grouped into classes that are associated with areas of the warehouse.

The location allocation decisions of class-based storage policies may be based on

simple rules such as turnover-based ordering, or an explicit optimization model

as in [18].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optimizationlearningalgorithmsandapplications-231204021346-9e8015c0/85/Optimization-Learning-Algorithms-and-Applications-pdf-70-320.jpg)

![58 H. Rummukainen

Goetschalckx and Ratliff [7] showed that information about storage durations

of arriving units can be used in a duration-of-stay-based (DOS-based) shared

storage policy that is more efficient than an optimal static dedicated (class-

based or product-based) storage policy. Kim and Park [13] used a subgradient

optimization algorithm for location allocation, assuming full knowledge of stor-

age times and amounts over the planning interval. Chen et al. [5] presented a

mixed-integer model and heuristic algorithms to minimize the peak transport

load of a DOS-based policy. In the present study, more complex DOS-based

policies are considered, with both dynamic class-based location assignment and

congestion costs.

Updating class-based assignments regularly was proposed by Pierre et al. [20],

and further studied by Kofler et al. [14], who called the problem multi-period

storage location assignment. Their problem was quite similar to the present

study, but both Pierre et al. and Kofler et al. applied heuristic rules without an

explicit mathematical programming model, and also included reshuffling moves.

The problem of yard planning in container terminals is closely related to

warehouse management, and a number of detailed optimization models have