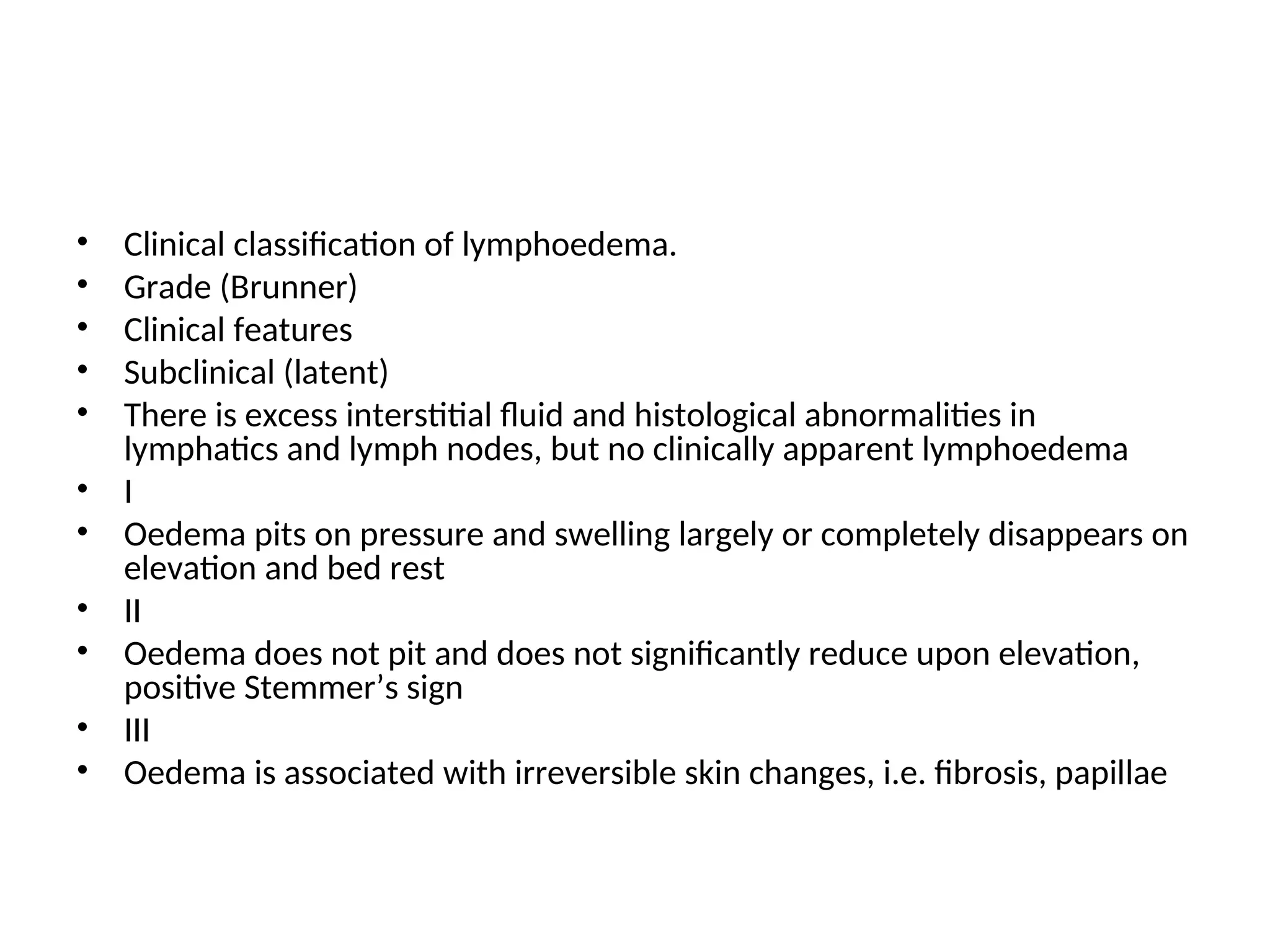

The document provides an extensive overview of the lymphatic system, outlining its components, functions, and the pathophysiology of various lymphatic disorders such as lymphoedema and acute lymphangitis. It discusses the physiological roles of lymphatics in fluid balance and immune response, as well as the mechanisms of lymph transport and the impact of underlying conditions on lymphatic health. Additionally, it covers classifications, clinical features, and risk factors associated with lymphatic conditions, including primary and secondary lymphoedema.