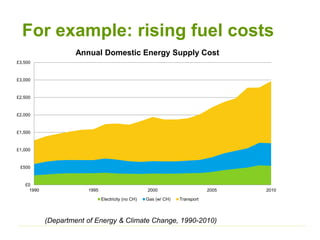

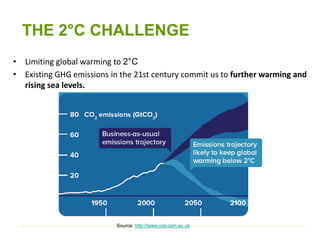

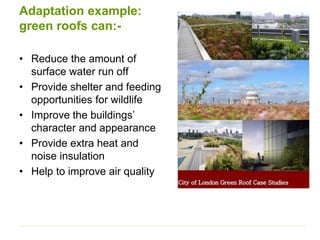

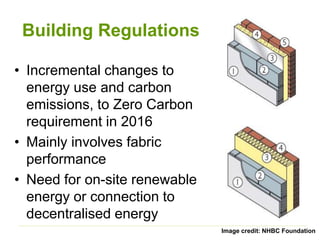

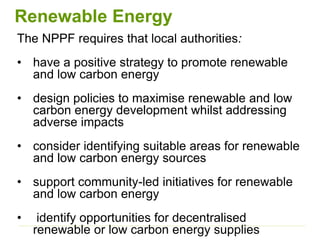

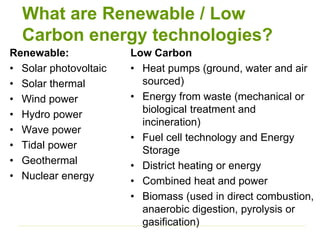

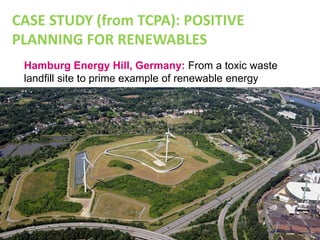

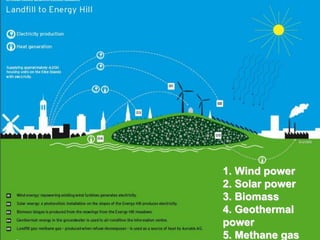

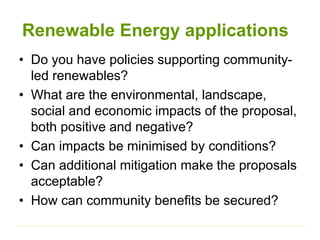

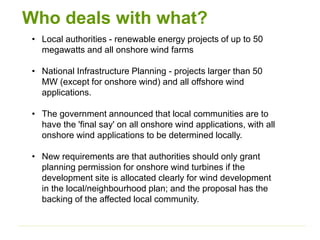

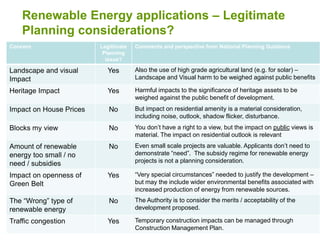

This document discusses how planning can help address climate change through sustainable energy opportunities and considerations for plan-making and development applications. It notes that planning can maximize economic benefits by reducing energy costs, help meet emissions targets, and build resilience to extreme weather. Issues to consider include rising fuel costs, the need to limit global warming, and examples of extreme weather events in the UK. The document provides guidance on how planning can adapt to and mitigate climate change through approaches like renewable energy development, sustainable construction standards, and sustainable drainage systems.