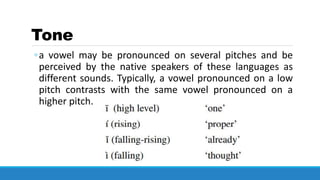

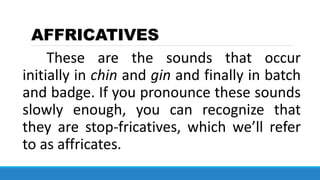

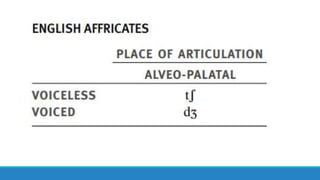

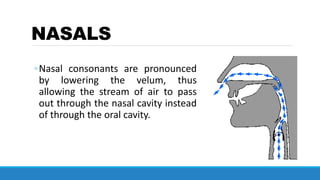

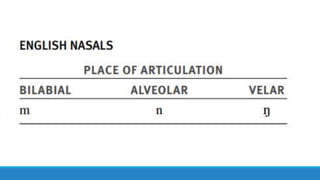

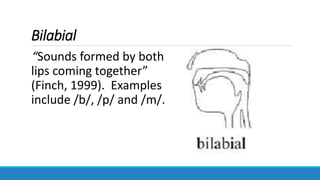

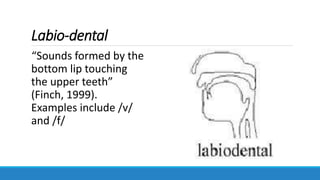

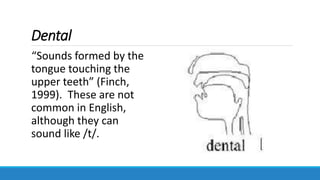

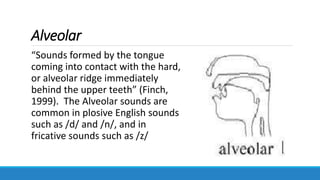

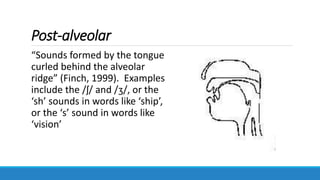

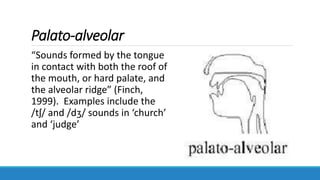

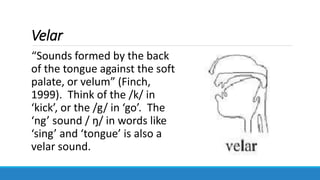

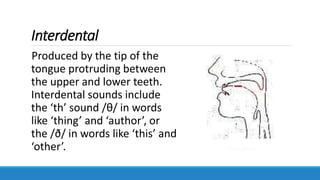

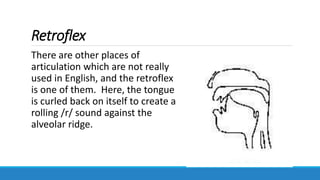

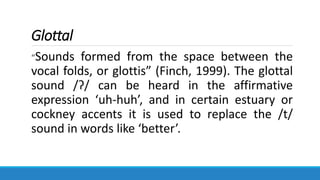

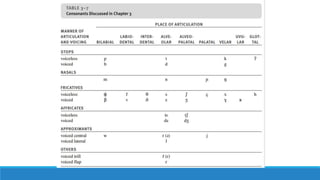

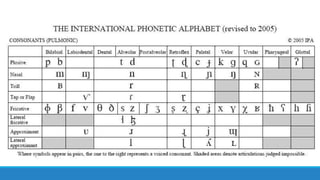

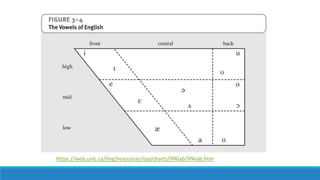

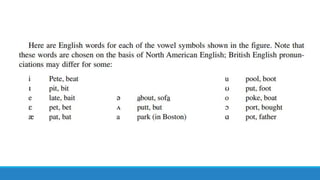

This document provides an overview of consonant and vowel sounds in phonetic terms. It describes the manner and place of articulation for consonants, including plosives, fricatives, affricates, approximants, nasals, and others. It also discusses vowel sounds and features like tenseness, length, nasalization, and tone. Diagrams and examples in English are provided to illustrate the various speech sounds.

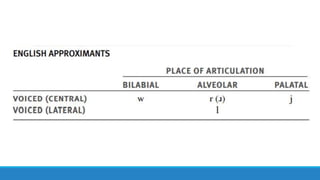

![APPROXIMANTS

oThey are produced by two articulators

approaching one another almost like fricatives

but not coming close enough to produce

friction.

oThe English approximants are [j], [r] (IPA [ɹ]), [l],

and [w]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonetics-1-230508072314-97973ad5/85/phonetics-1-pptx-7-320.jpg)

![◦Because [r] is pronounced by channeling air

through the central part of the mouth, it is

called a central approximant. To pronounce

[l], air is channeled on one or both sides of the

tongue to make a lateral approximant. To

distinguish them from the other approximants,

[r] and [l] are sometimes called liquids.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonetics-1-230508072314-97973ad5/85/phonetics-1-pptx-8-320.jpg)

![NASALS

◦English has three nasal stops:

[m] as in mad, drummer, cram;

[n] as in new, sinner, ten; and a

third, symbolized by [ŋ].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonetics-1-230508072314-97973ad5/85/phonetics-1-pptx-11-320.jpg)

![English speakers may think of [ŋ] as a

combination of [n] and [g], but it is actually a

single sound

singer vs. finger](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonetics-1-230508072314-97973ad5/85/phonetics-1-pptx-13-320.jpg)

![DIPTHONGS

English also has diphthongs, represented by pairs

of symbols to capture the fact that a diphthong is a

vowel sound for which the tongue starts in one place

and glides to another.

[aj] (as in ride)

[aw] (as in loud)

[ɔj] (as in boy, toy)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonetics-1-230508072314-97973ad5/85/phonetics-1-pptx-35-320.jpg)

![contrast between [i] of peat and of pit is

in part a tense/lax contrast; likewise for the

vowels in bait/bet and in cooed/could](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phonetics-1-230508072314-97973ad5/85/phonetics-1-pptx-37-320.jpg)