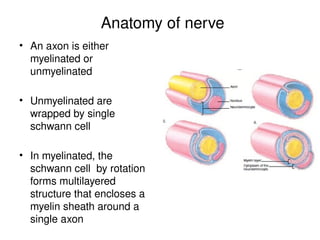

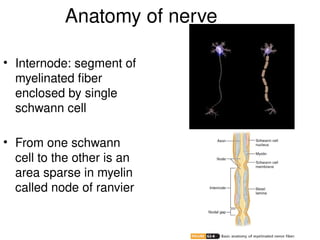

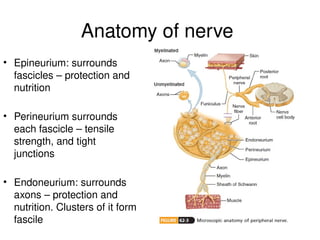

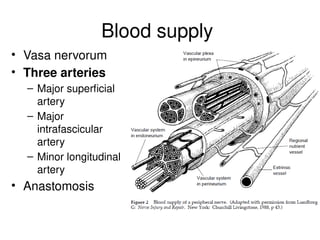

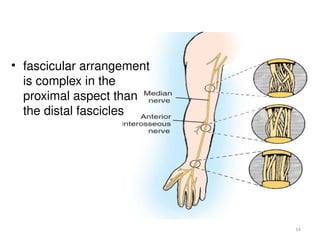

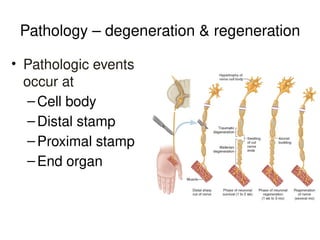

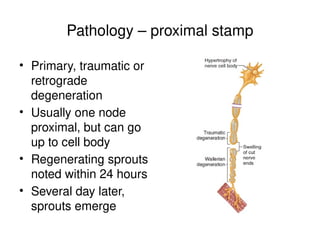

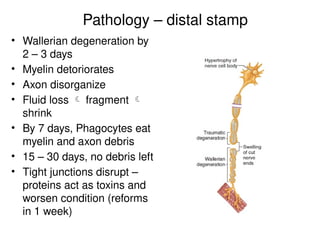

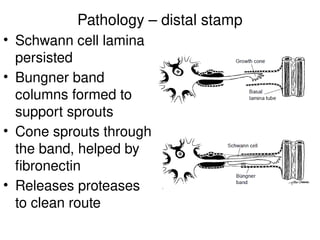

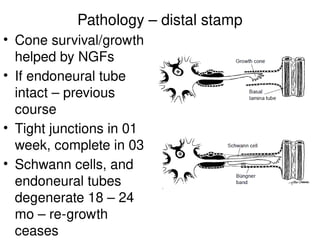

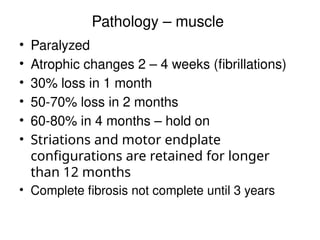

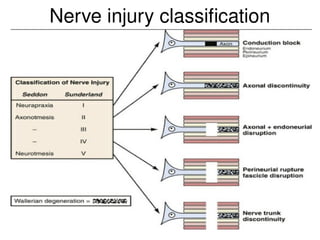

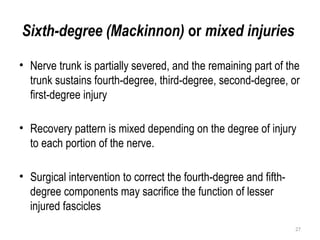

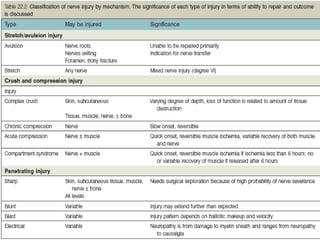

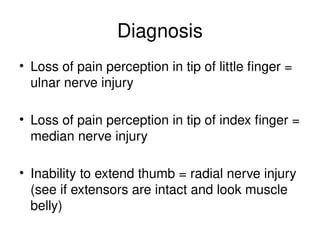

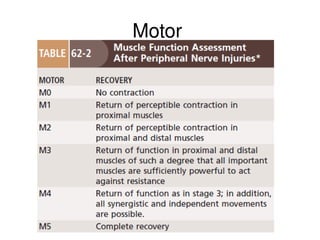

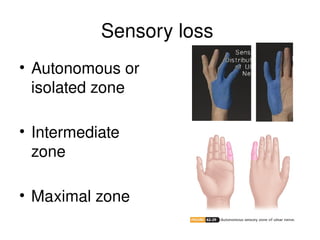

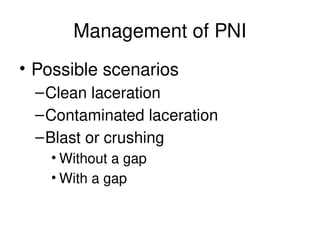

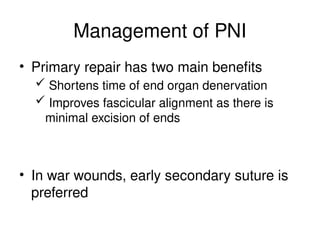

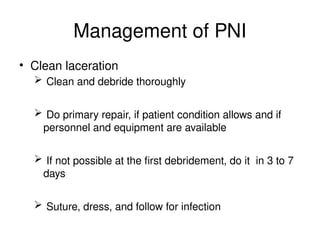

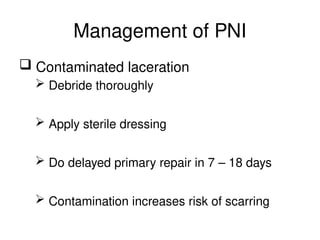

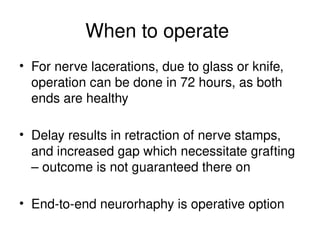

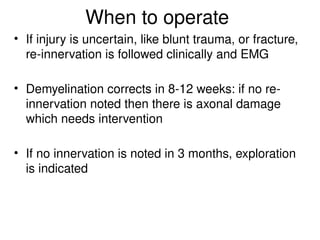

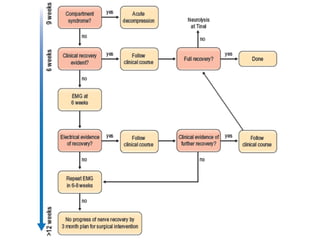

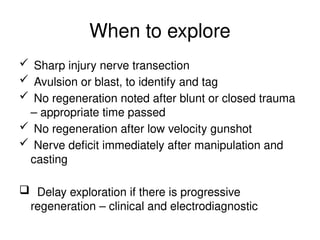

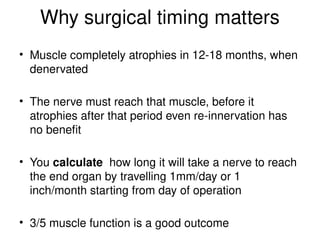

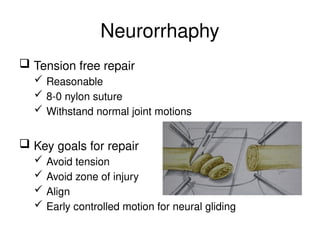

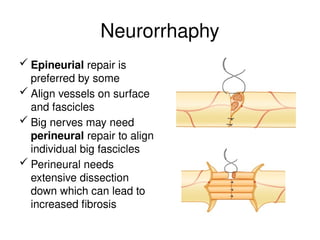

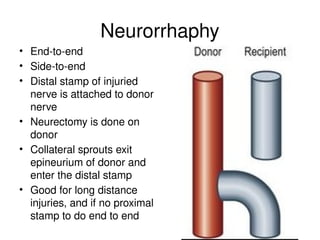

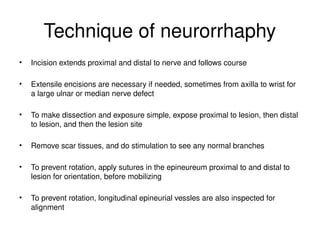

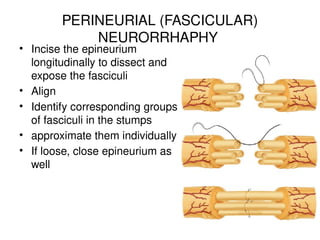

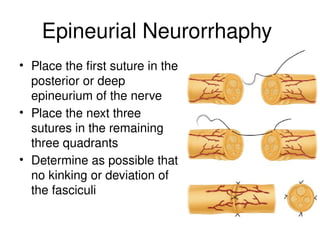

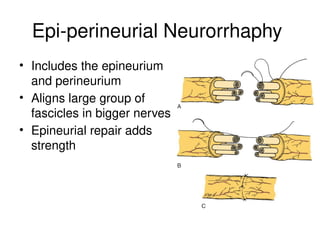

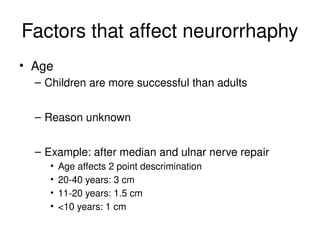

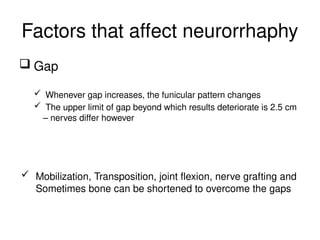

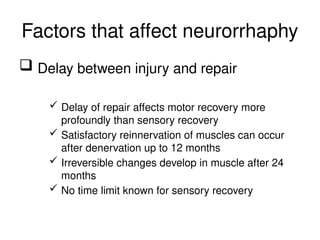

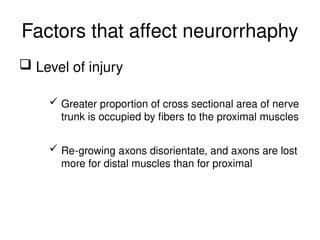

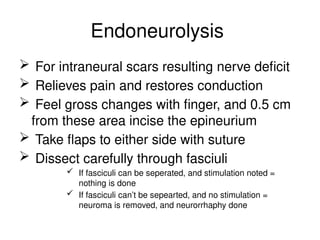

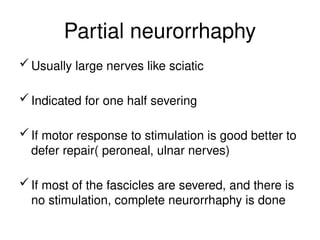

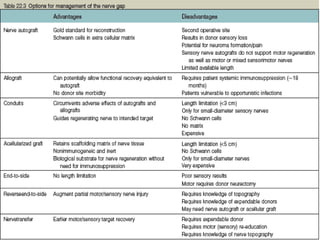

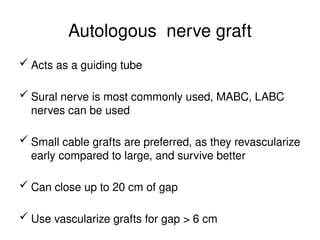

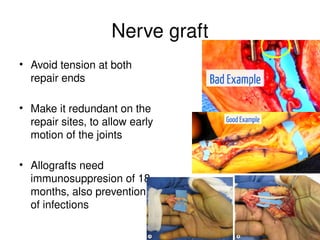

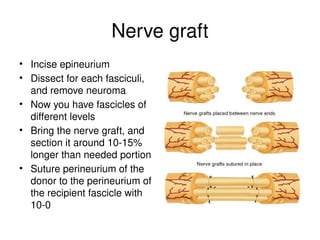

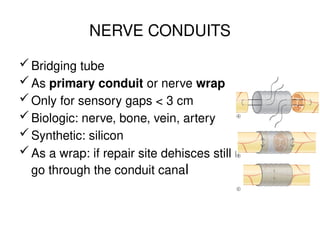

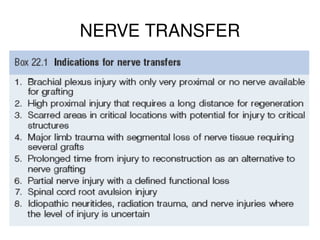

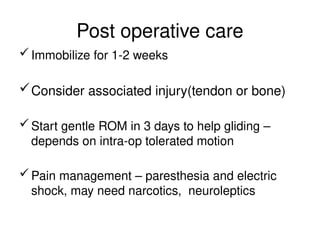

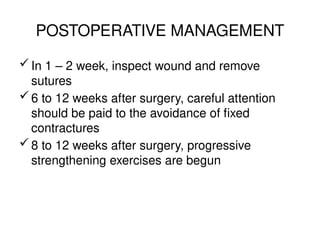

El documento detalla la anatomía, patología, características y tratamiento de las lesiones de nervios periféricos, describiendo la estructura del sistema nervioso y los tipos de lesiones que pueden ocurrir. Se analizan los mecanismos de degeneración y regeneración nerviosa, así como los métodos de diagnóstico y las opciones de tratamiento, incluida la cirugía. Se enfatiza la importancia de la intervención temprana y la alineación adecuada de los fascículos nerviosos para una recuperación efectiva.