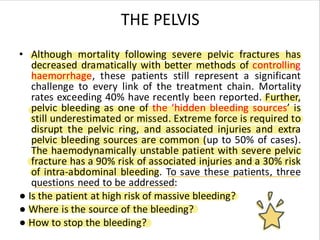

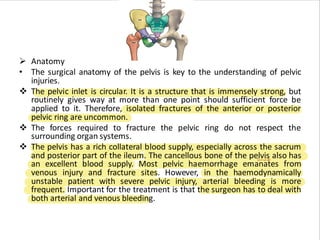

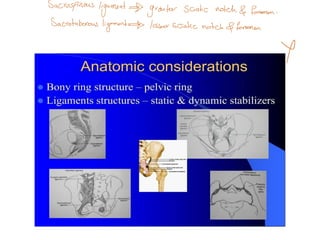

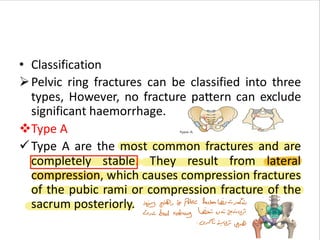

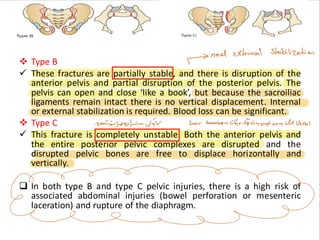

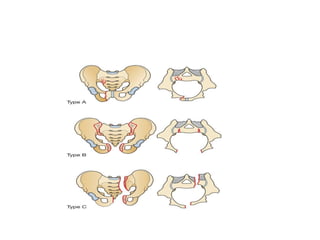

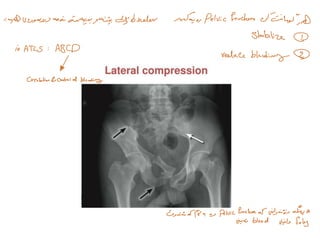

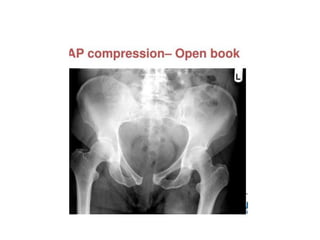

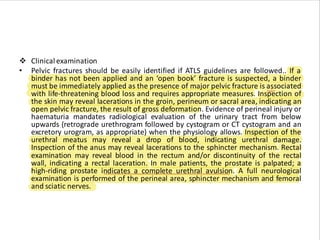

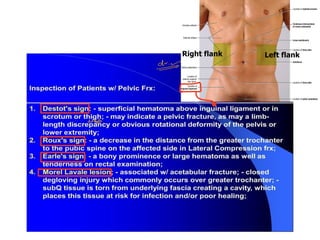

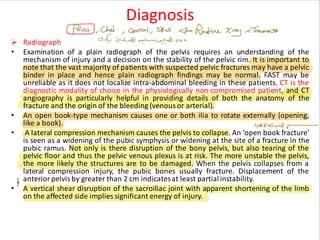

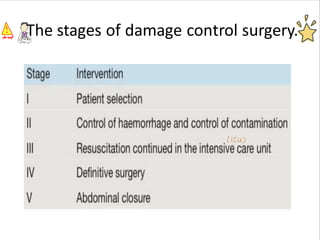

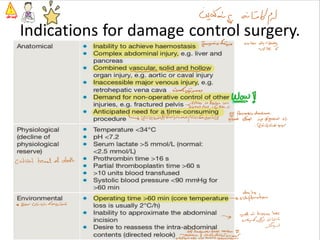

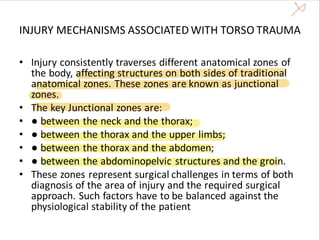

The document discusses the challenges and management strategies for severe pelvic fractures and associated abdominal trauma, noting a significant mortality rate despite advancements in hemorrhage control. It outlines the surgical anatomy of the pelvis, classification of pelvic ring fractures, clinical examination techniques, and essential management protocols, including damage control surgery. Emphasis is placed on timely intervention, multidisciplinary approaches, and the importance of effective hemorrhage control in improving patient outcomes.