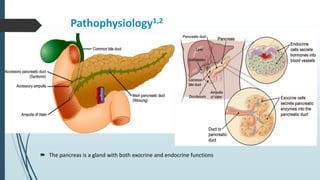

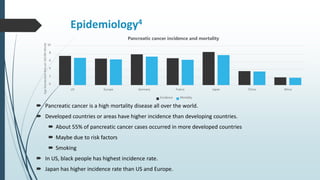

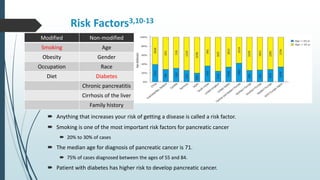

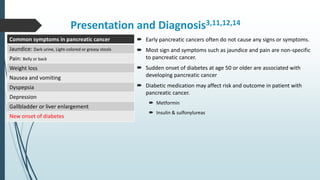

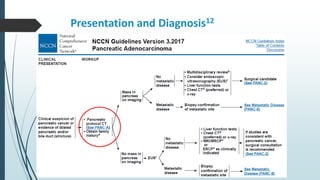

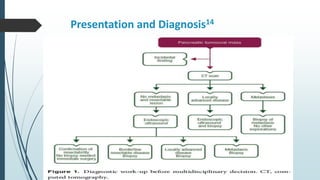

The document provides a comprehensive overview of pancreatic cancer, detailing its pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment options. It highlights the high mortality associated with the disease, the significance of early diagnosis, and various treatment modalities including surgery, chemotherapy, and investigational therapies. Notably, the text emphasizes the limited survival rates, particularly in advanced stages, and the potential for emerging immunotherapies.

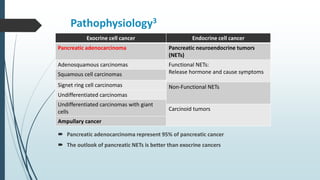

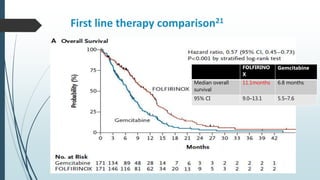

![First line therapy comparison21

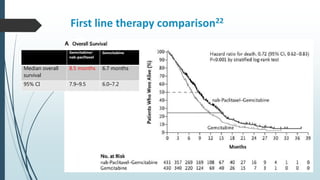

It was a randomized, phase 2–3 trial of receiving FOLFIRINOX or gemcitabine.

Patients with confirmed, measurable metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma and treatment-naïve.

The primary end point was overall survival.

FOLFIRINOX

(N = 171)

Gemcitabine

(N = 171)

Objective Response Rate, n (%)

[95% CI]

P value

54 (31.6)

[24.7–39.1]

< 0.001

16 (9.4)

[5–14.7]

—

Response, n (%)

Complete response

Partial response

Stable disease

Progressive disease

Could not be evaluated

1 (0.6)

53 (31.0)

66 (38.6)

26 (15.2)

25 (14.6)

0

16 (9.4)

71 (41.5)

59 (34.5)

25 (14.6)

Rate of disease control, n (%)

[95% CI]

P value

120 (70.2)

[62.7–76.9]

< 0.001

87 (50.9)

[43.1–58.6]

—](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pancreaticcancerpresentaion-171024180556/85/Pancreatic-cancer-presentaion-33-320.jpg)

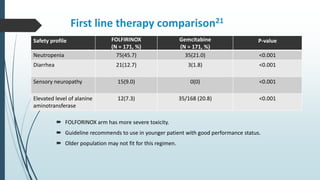

![First line therapy comparison22

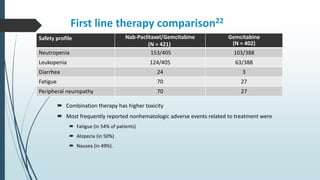

It was a randomized, phase 3 trial receiving of Nab-Paclitaxel/gemcitabine or gemcitabine.

Patients with confirmed, measurable metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma and treatment-naïve.

The primary end point was overall survival.

Nab-Paclitaxel/Gemcitabine

(N = 431)

Gemcitabine

(N = 430)

Objective Response Rate, n (%)

[95% CI]

P value

99 (23)

[19–27]

< 0.001

31 (7)

[5–10]

—

Response, n (%)

Complete response

Partial response

Stable disease

Progressive disease

Could not be evaluated

1 (<1)

98 (23)

118 (27)

86 (20)

128 (30)

0

31 (7)

122 (28)

110 (26)

167 (39)

Rate of disease control, n (%)

[95% CI]

P value

206 (48)

[43–53]

< 0.001

141 (33)

[28–37]

—](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pancreaticcancerpresentaion-171024180556/85/Pancreatic-cancer-presentaion-36-320.jpg)