Pulmonary artery banding (PAB) is a palliative surgical technique for congenital heart defects, primarily used to reduce excessive pulmonary blood flow and protect the pulmonary vasculature. Although its usage has declined due to more definitive surgical interventions, PAB remains important for specific patients, especially those with transposition of the great arteries or significant left-to-right shunting. The procedure involves placing a band around the pulmonary artery to manage blood flow and prevent heart failure, with careful consideration of patient selection, anatomical factors, and postoperative care.

![History of the Procedure

• The first description of pulmonary artery banding (PAB) in the

literature was a report by Muller and Dammann at the University of

California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in 1951.

• In this report, Muller and Dammann described palliation by the

"creation of pulmonary stenosis" in a 5-month-old infant who had a

large ventricular septal defect (VSD) and pulmonary overcirculation.

• Following this report, multiple studies were published demonstrating

the effectiveness of this technique in infants with congestive heart

failure (CHF) caused by large VSDs, complex lesions (eg,

atrioventricular canal [AVC] defects), and tricuspid atresia.

• Although the use of PAB has declined, it remains an essential

technique for comprehensive surgical treatment in patients with

congenital heart disease. PAB is a palliative but not a curative

surgical procedure.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pabandingnew-1803131814071-240924062810-d8779a5b/75/PA-banding-basic-and-surgical-and-complications-4-2048.jpg)

![Contraindications

• Patients who have single ventricle defects in which the

aorta arises from an outflow chamber (eg, double inlet left

ventricle [LV], tricuspid atresia with transposition of the

great arteries [TGA]) have the potential for development of

significant subaortic obstruction.

• Pulmonary artery banding (PAB) is contraindicated in the

presence of such obstruction and in patients who are at

high risk for such obstruction.

• The ventricular hypertrophy that develops in response to

PAB may cause rapid progression of subaortic obstruction

leading to a combination of both ventricles having outflow

tract obstruction and progressive hypertrophy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pabandingnew-1803131814071-240924062810-d8779a5b/75/PA-banding-basic-and-surgical-and-complications-16-2048.jpg)

![• The MPA and aorta are exposed, and the band is

prepared for placement.

• The estimated band circumference is marked on the

umbilical tape with fine sutures according to the Trusler

formula.

• PAB circumference in patients with noncyanotic

nonmixing lesions (eg, ventricular septal defect [VSD]) is

20 mm + 1 mm/kg body weight. For patients with mixing

lesions (eg, D-transposition of the great arteries [TGA]

with VSD), the formula is 24 mm + 1 mm/kg body weight.

In patients with single ventricles in whom the Fontan

procedure is planned, an intermediate circumference of

22 mm + 1 mm/kg body weight is preferred.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pabandingnew-1803131814071-240924062810-d8779a5b/75/PA-banding-basic-and-surgical-and-complications-23-2048.jpg)

![• An adequate atrial communication should be confirmed

preoperatively in patients with single ventricle physiology,

including transposition with VSD complexes. A balloon

atrial septostomy is useful in these situations.

• Kotani and colleagues measured intraoperative aortic

blood flow using a Transonic flow probe and found that

aortic blood flow increased by approximately 40% after

successful PAB. Their data suggested that higher pre-PAB

Qp/Qs (pulmonary [Qs]-systemic [Qp] blood flow ratio)

predicted a higher percentage increase in aortic flow.

• Three patients with less than a 20% increase in aortic

blood flow died, required re-PAB, or developed

ventricular dysfunction.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pabandingnew-1803131814071-240924062810-d8779a5b/75/PA-banding-basic-and-surgical-and-complications-31-2048.jpg)

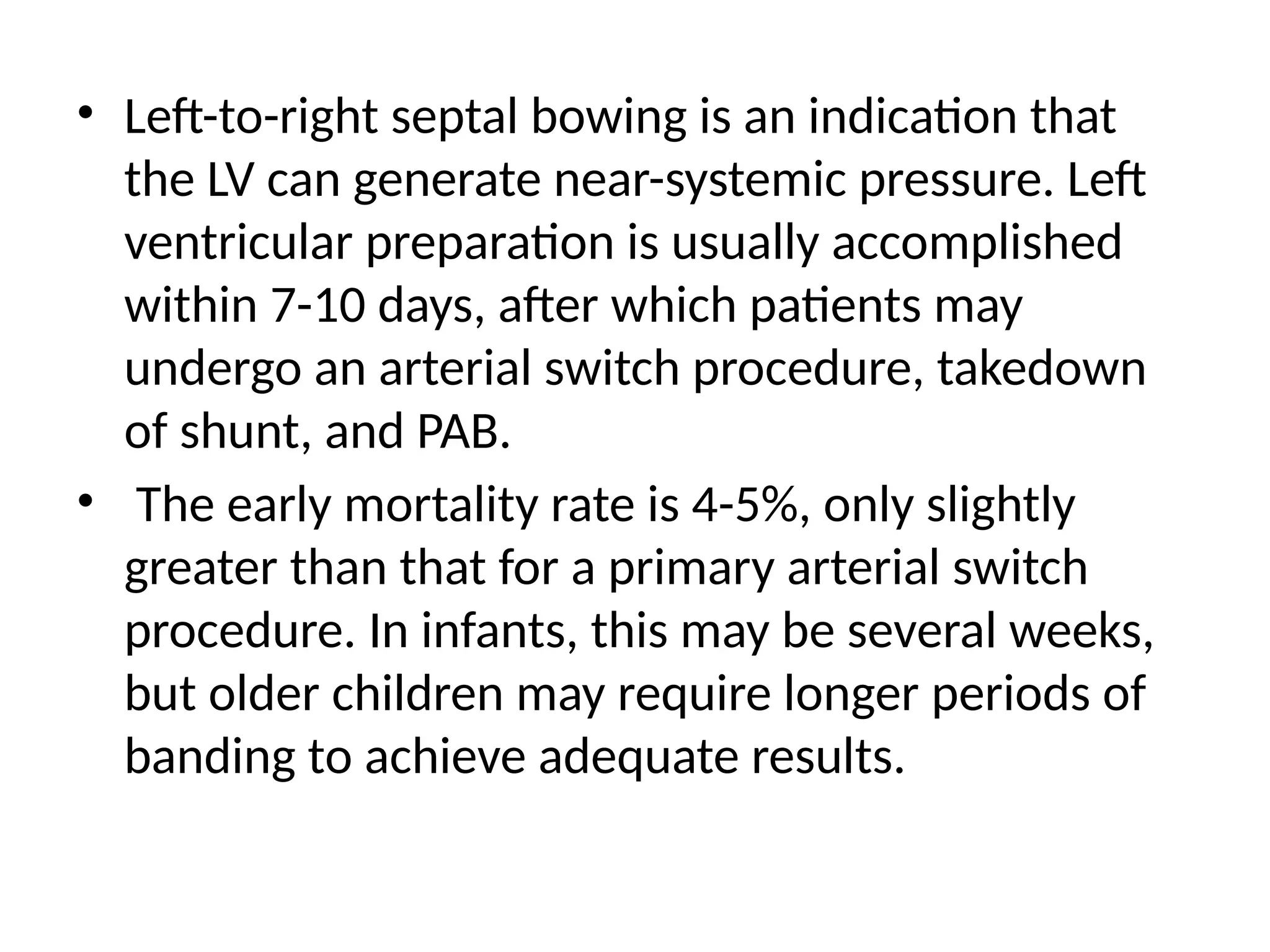

![• PAB takedown is usually performed at the time of the

intracardiac repair through a median sternotomy.

Generally, the repair is completed first and the PAB

removal is performed at the end of the procedure.

• The band is dissected free from surrounding scar tissue

and removed. The area of banding usually remains

stenotic and requires repair.

• This repair can be achieved by resection and end-to-end

anastomosis of the proximal and distal MPA or by

vertical incision of the MPA followed by pericardial (or

polytetrafluoroethylene [PTFE]) patch repair of the

arteriotomy

• The repair must ensure relief of any branch PA stenosis

that may exist as a consequence of the PAB.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pabandingnew-1803131814071-240924062810-d8779a5b/75/PA-banding-basic-and-surgical-and-complications-33-2048.jpg)