The document discusses the concept of obedience to authority, examining Stanley Milgram's shock experiments and detailing factors that lead individuals to inflict harm under authority. It explores findings from political science, emphasizing definitions of democracy, individual rights, and the importance of a constitution that limits government power while providing for individual freedoms. Additionally, it highlights the foundational ideas of social contracts and the Bill of Rights in protecting citizen liberties in the context of the American political system.

![electors] in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct. .

. .”) Bush’s lawyers also argued that without specific standards

to determine the “intent” of the voter, different vote counters

would use different standards (counting or not counting chads

that were “dimpled,” “pregnant,” “indented,” and so on).

Without uniform rules, such a recount would violate the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

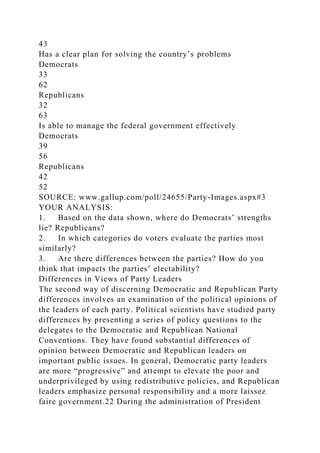

In Bush v. Gore, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed (by a seven-to-

two vote) that the Florida court had created “constitutional

problems” involving the equal protection clause, and the Court

ordered (by a five-to-four vote) that the hand count be ended

altogether. The effect of the decision was to reinstate the

Florida secretary of state’s certification of Bush as the winner

of Florida’s 25 electoral votes and consequently the winner of

the Electoral College vote for president by the narrowest of

margins—271 to 267.

For the first time in the nation’s history, a presidential election

was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Perhaps only the

Supreme Court possesses sufficient legitimacy in the mind of

the American public to bring about a resolution to the closest

presidential electoral vote in history.

The Power of the Courts

The founders of the United States viewed the federal courts as

the final bulwark against threats to individual liberty. Since

Marbury v. Madison first asserted the U.S. Supreme Court’s

power of judicial review over congressional acts, the federal

courts have struck down more than eighty congressional laws

and uncounted state laws that they believed conflicted with the

Constitution.

Judicial review and the right to interpret the meaning and

decide the application of the Constitution and laws of the

United States are great sources of power for judges.16

Key Court Decisions

Some of the nation’s most important policy decisions have been

made by courts rather than by executive or legislative bodies.

The federal courts took the lead in eliminating racial](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optionbobediencetoauthoritycauseandeffect-221108012007-69b56597/85/Option-B-Obedience-to-Authority-Cause-and-Effect-First-read-St-docx-42-320.jpg)

![performance raised the only issue that might conceivably defeat

him—his age. The president had looked and sounded old.

In preparation for the second debate, Reagan decided, without

telling his aides, to lay the perfect trap for his questioners.

When asked about his age and capacity to lead the nation, he

responded with a serious deadpan expression to a hushed

audience and waiting America: “I want you to know that I will

not make age an issue in this campaign. I am not going to

exploit for political purposes [pause] my opponent’s youth and

inexperience.” The studio audience broke into uncontrolled

laughter. Even Mondale had to laugh. With a classic one-liner,

the president buried the age issue and won not only the debate

but also the election.

The Bush–Dukakis Debates

In 1988 Michael Dukakis ensured his defeat with a cold,

detached performance in the presidential debates, beginning

with the very first question. When CNN anchor Bernard Shaw

asked, “Governor, if Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered,

would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?”

The question demanded an emotional reply. Instead, Dukakis

responded with an impersonal recitation of his stock positions

on crime, drugs, and law enforcement. George H. W. Bush

seized the opportunity to establish an intimate, warm, and

personal relationship with the viewers: “I do believe some

crimes are so heinous, so brutal, so outrageous . . . I do believe

in the death penalty.” Voters responded to Bush, electing him.

The Clinton–Bush–Perot Debates

The three-way presidential debates of 1992 drew the largest

television audiences in the history of presidential debates. In

the first debate, Ross Perot’s Texas twang and down-home

folksy style stole the show. But it was Bill Clinton’s smooth

performance in the second debate, with its talk-show format,

that seemed to wrap up the election. Ahead in the polls, Clinton

appeared at ease walking about the stage and responding to

audience questions with sympathy and sincerity. By contrast,

George H. W. Bush appeared stiff and formal and somewhat ill](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/optionbobediencetoauthoritycauseandeffect-221108012007-69b56597/85/Option-B-Obedience-to-Authority-Cause-and-Effect-First-read-St-docx-57-320.jpg)