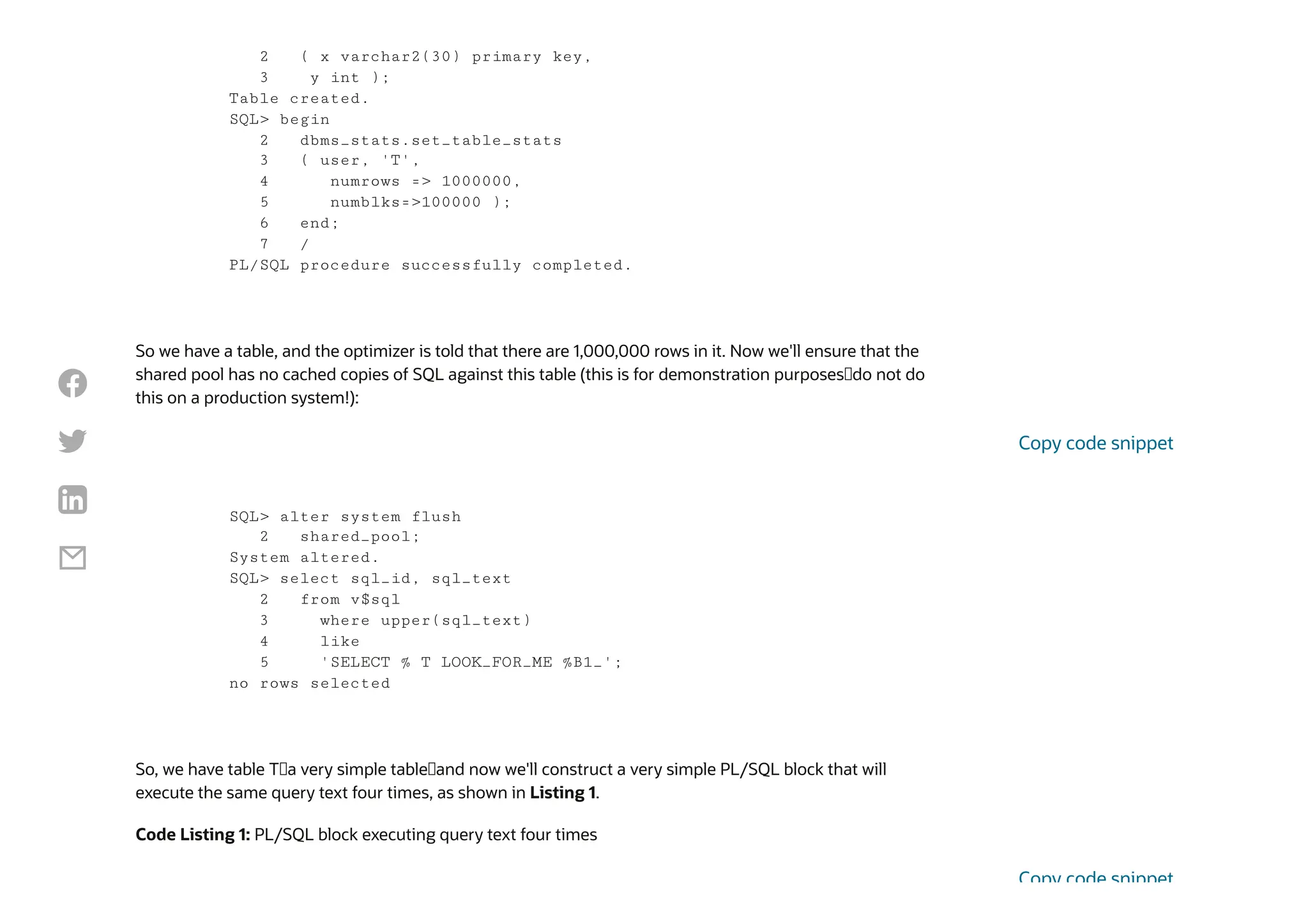

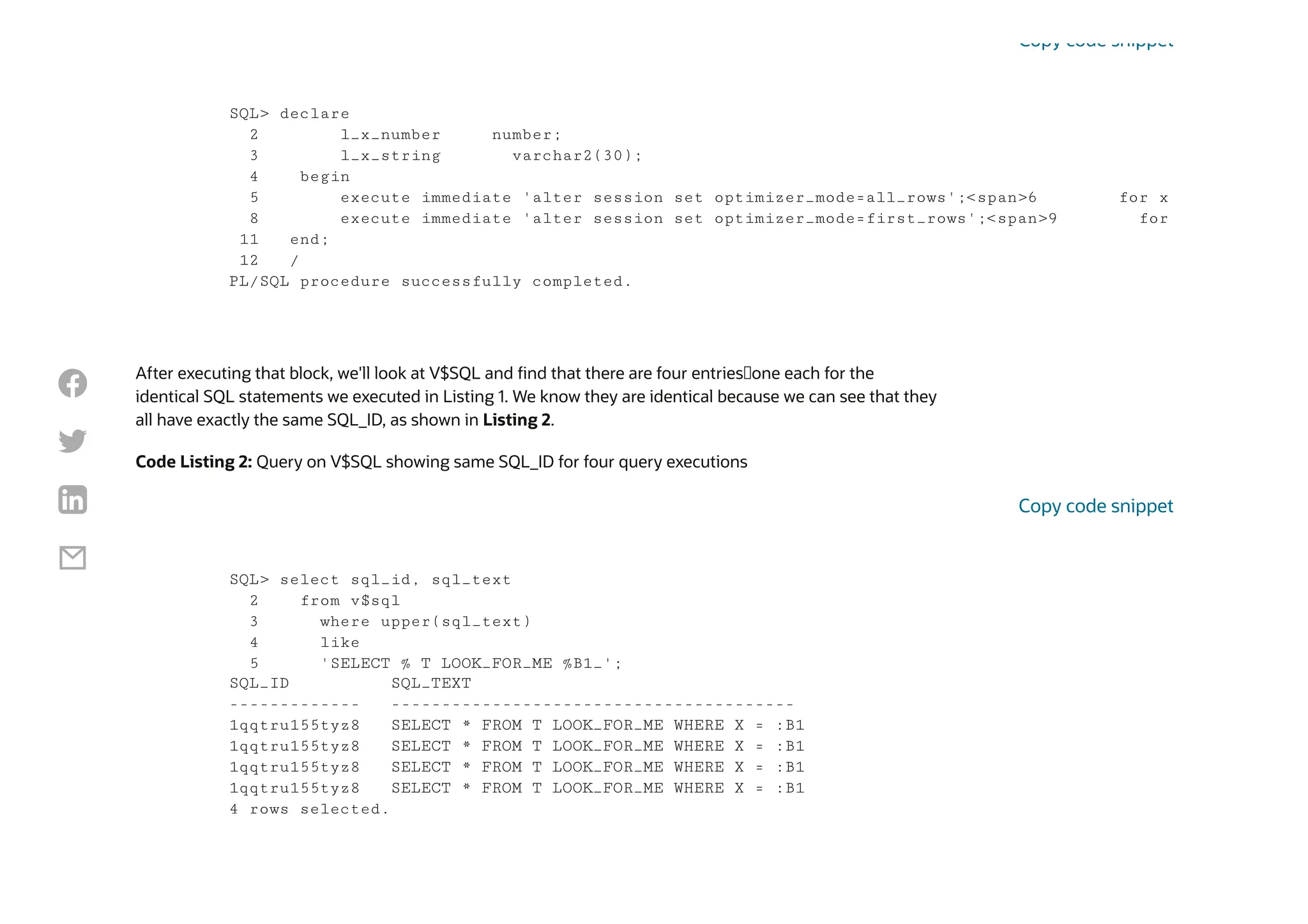

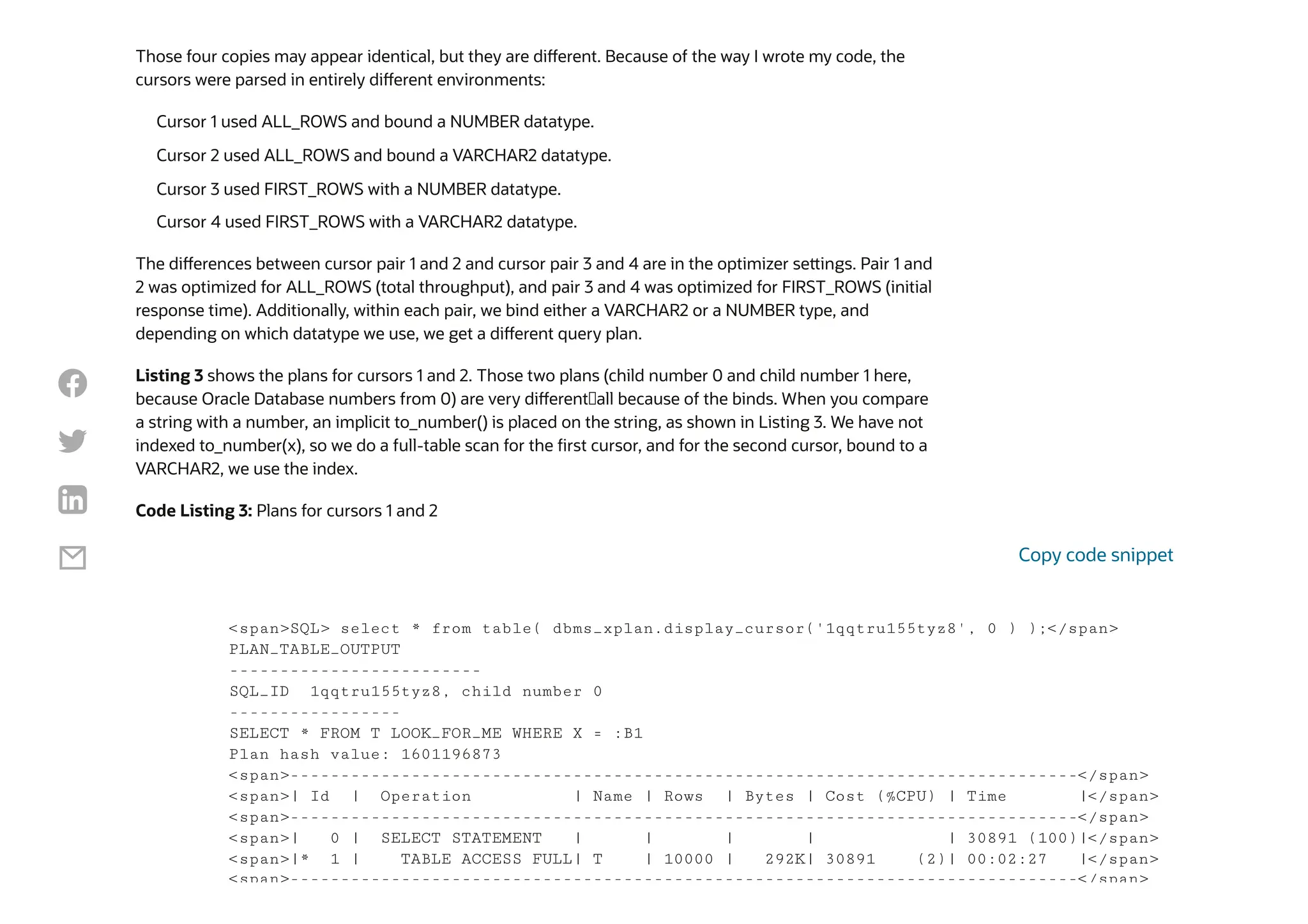

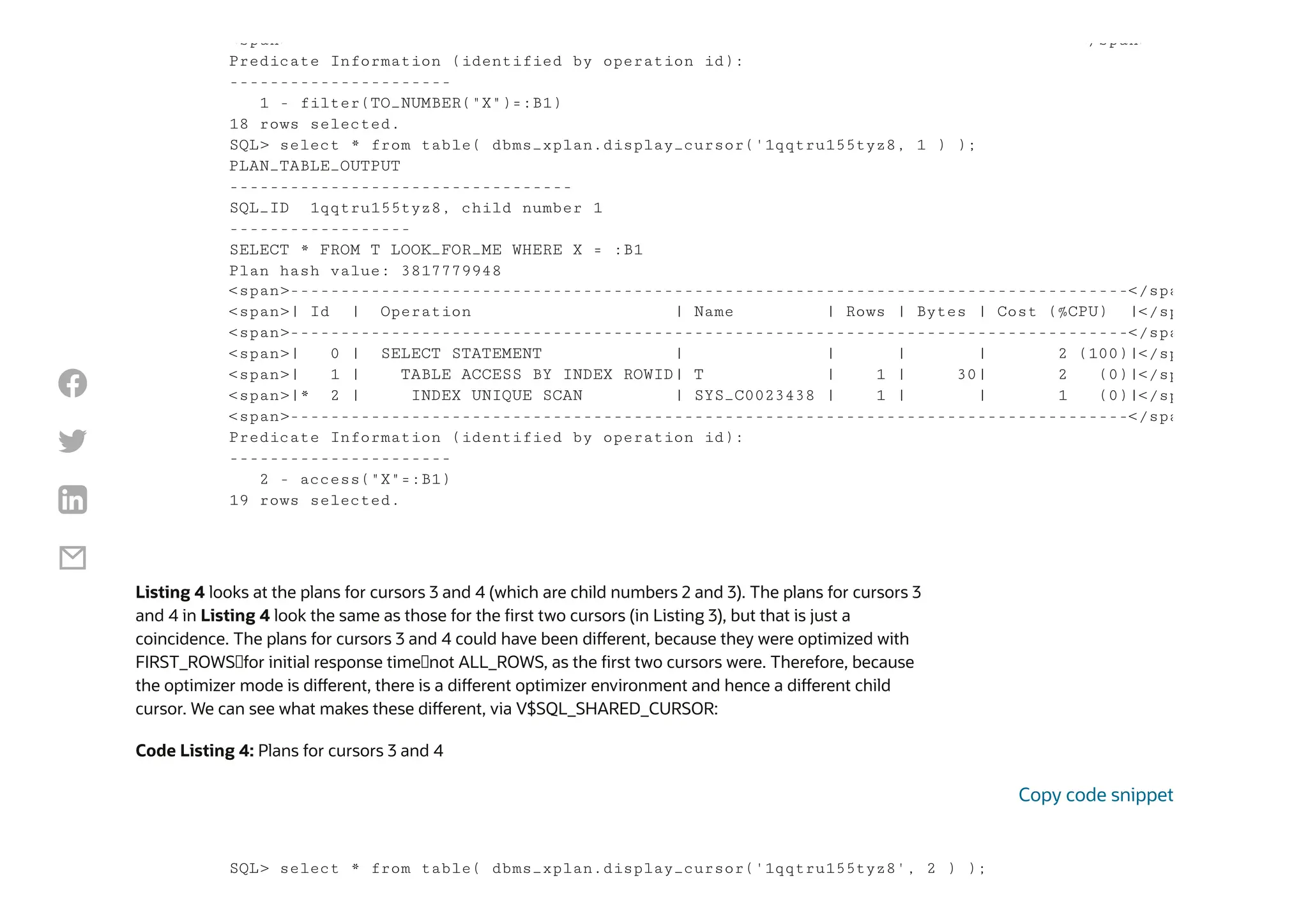

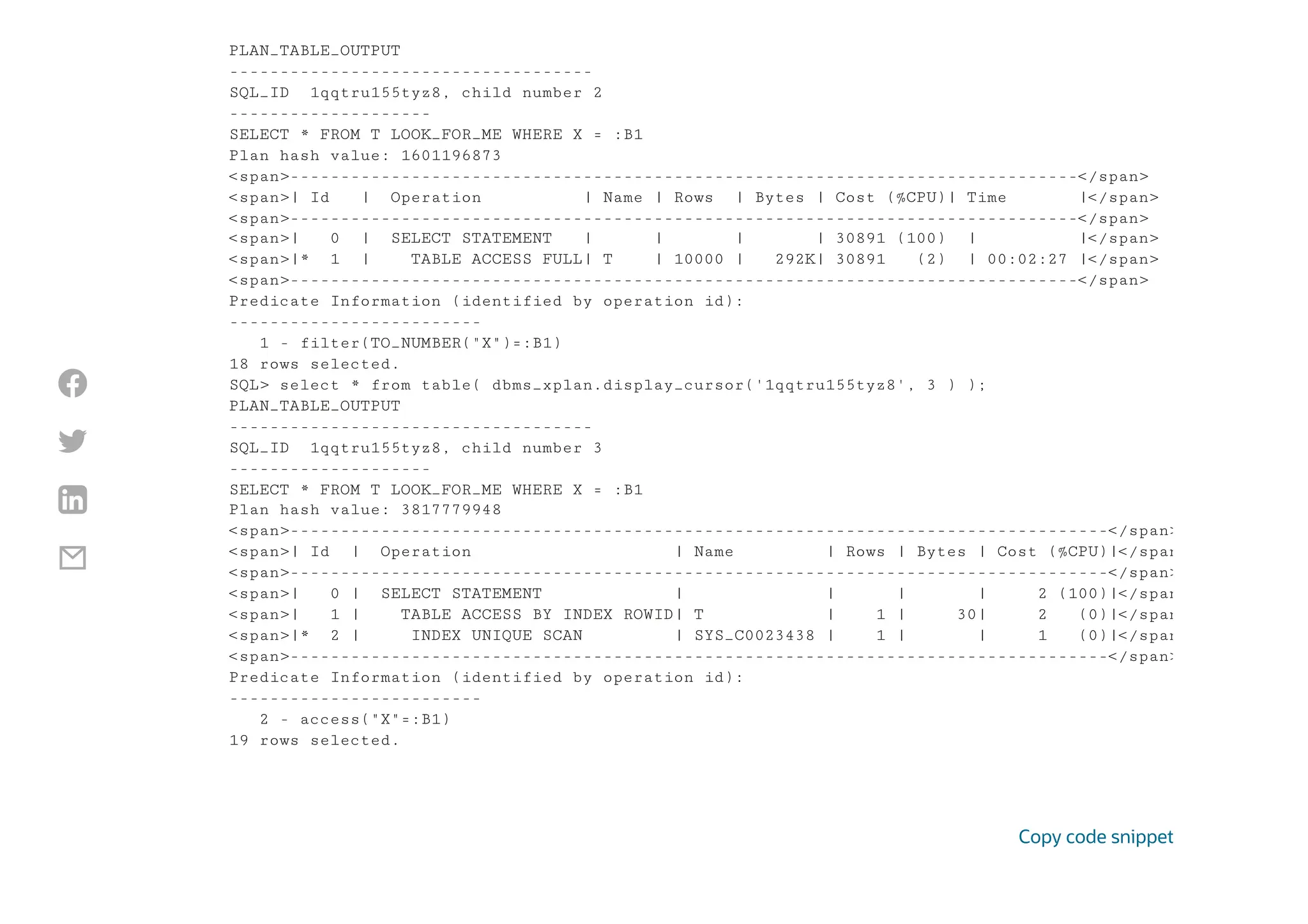

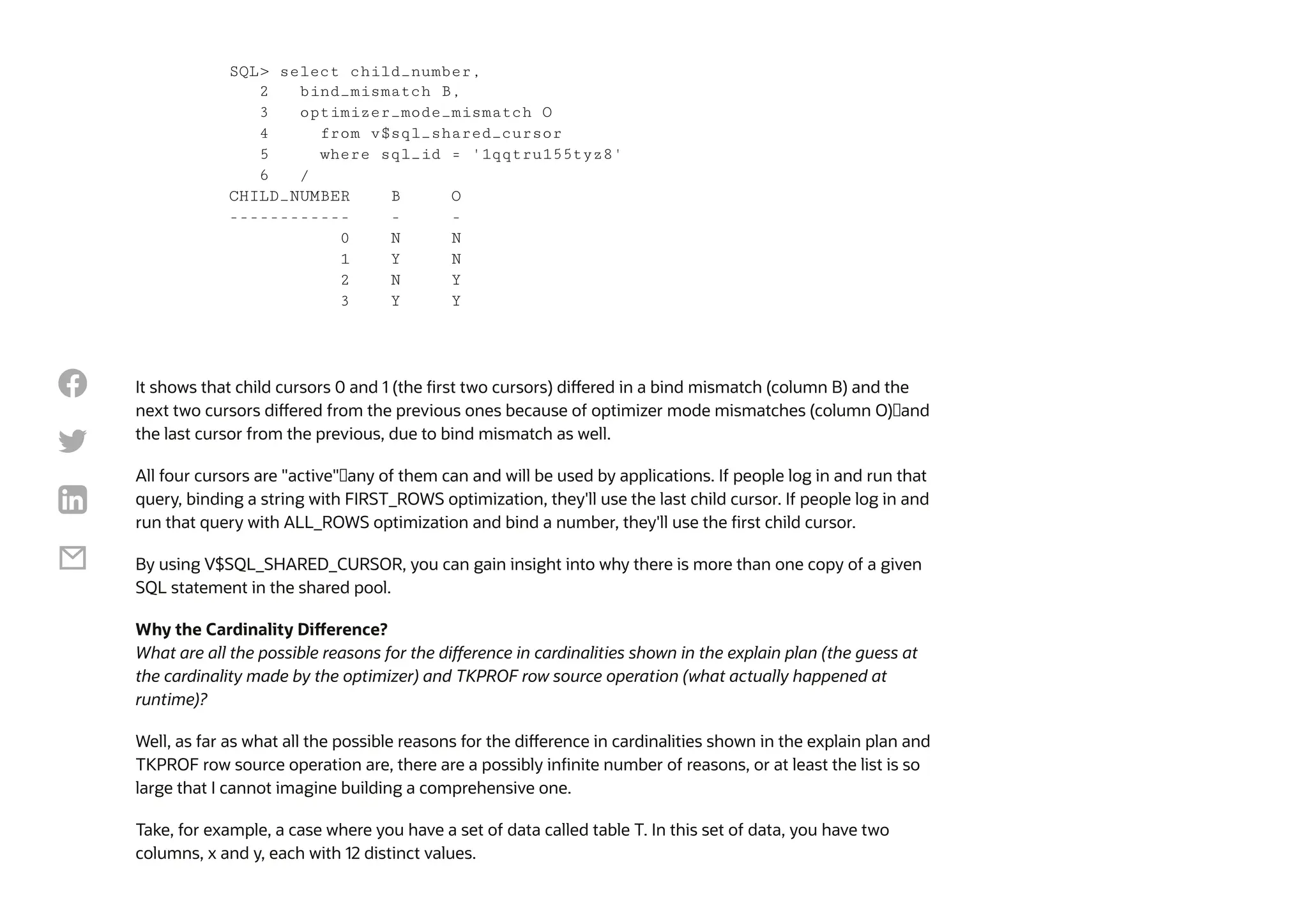

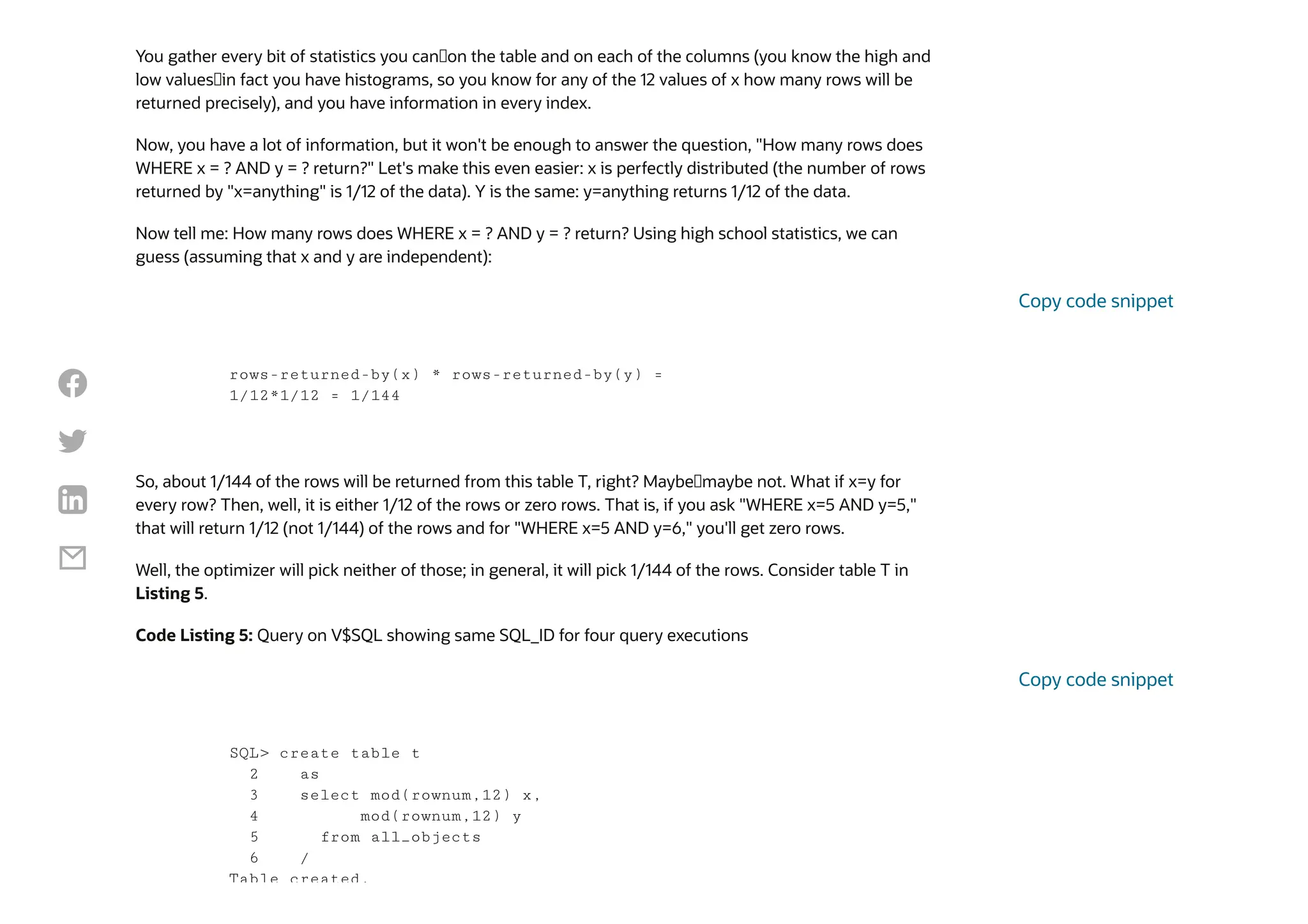

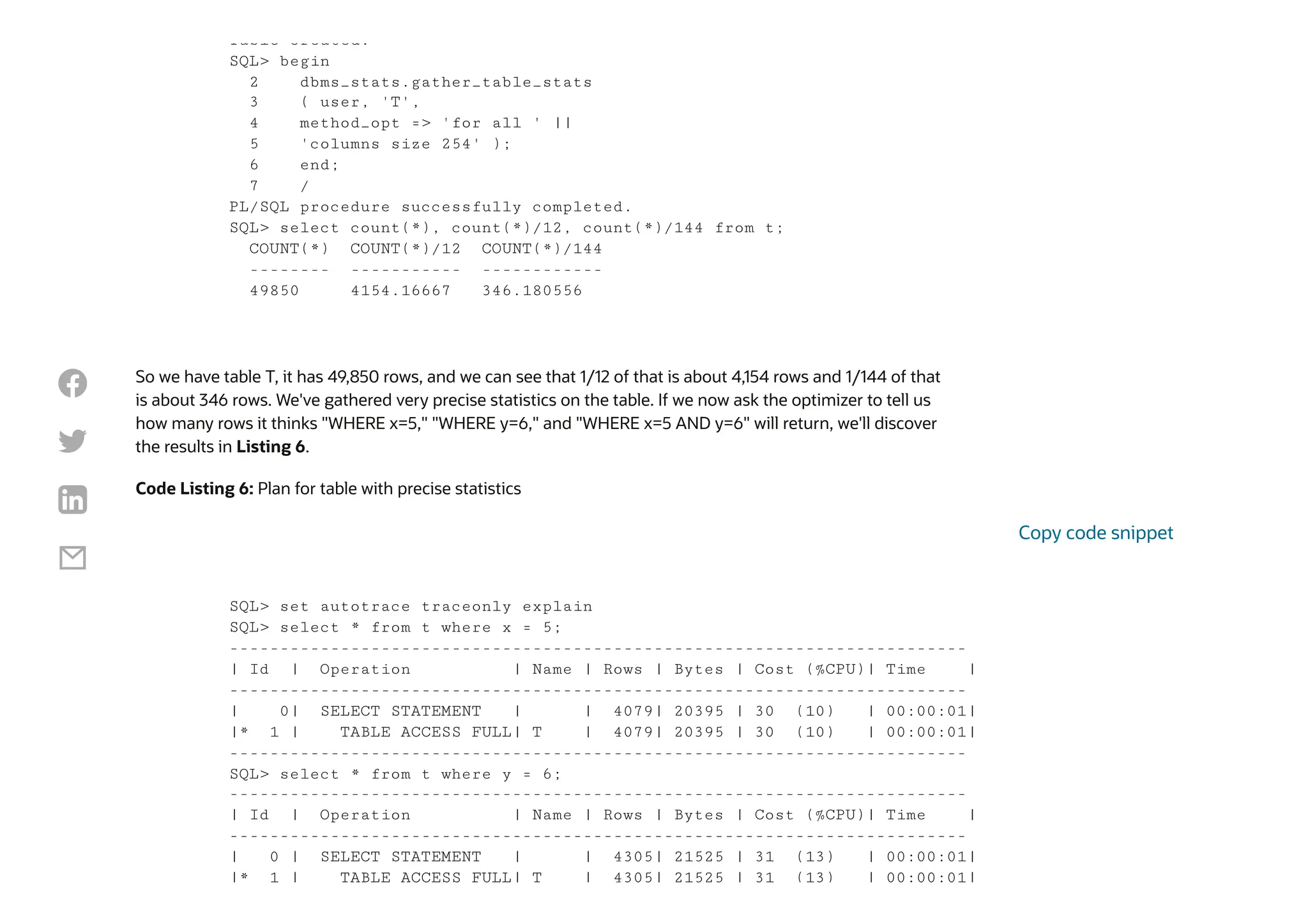

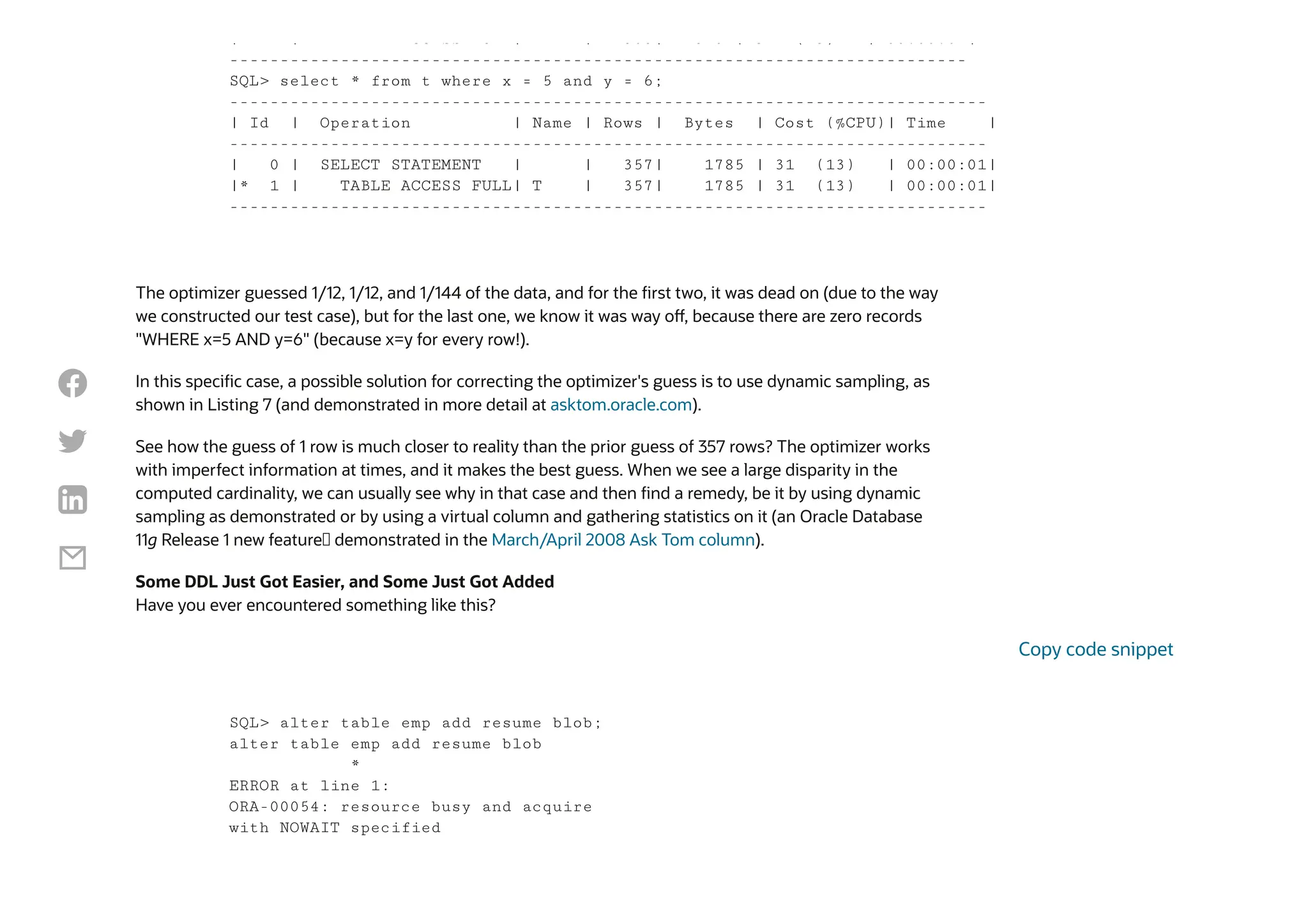

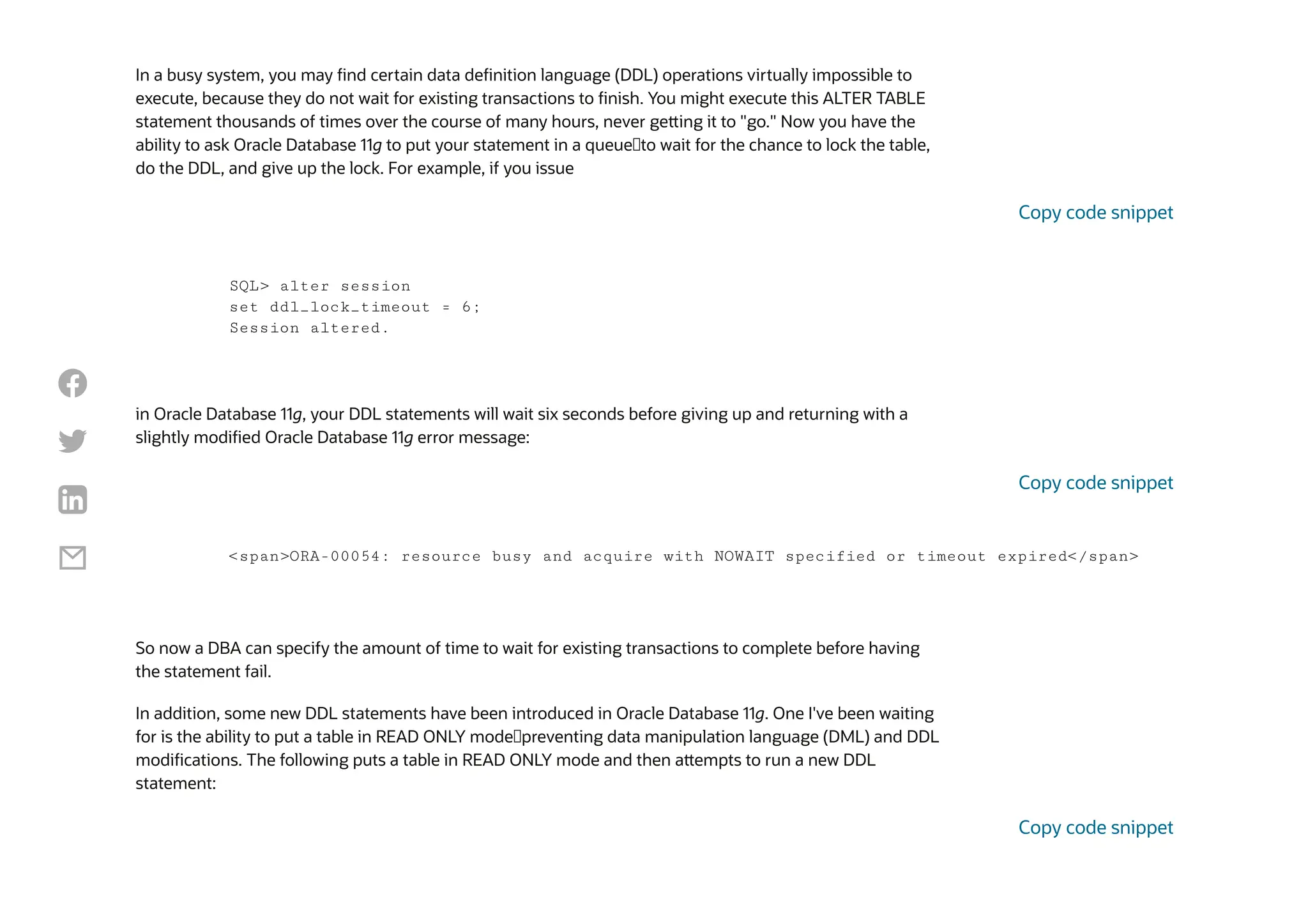

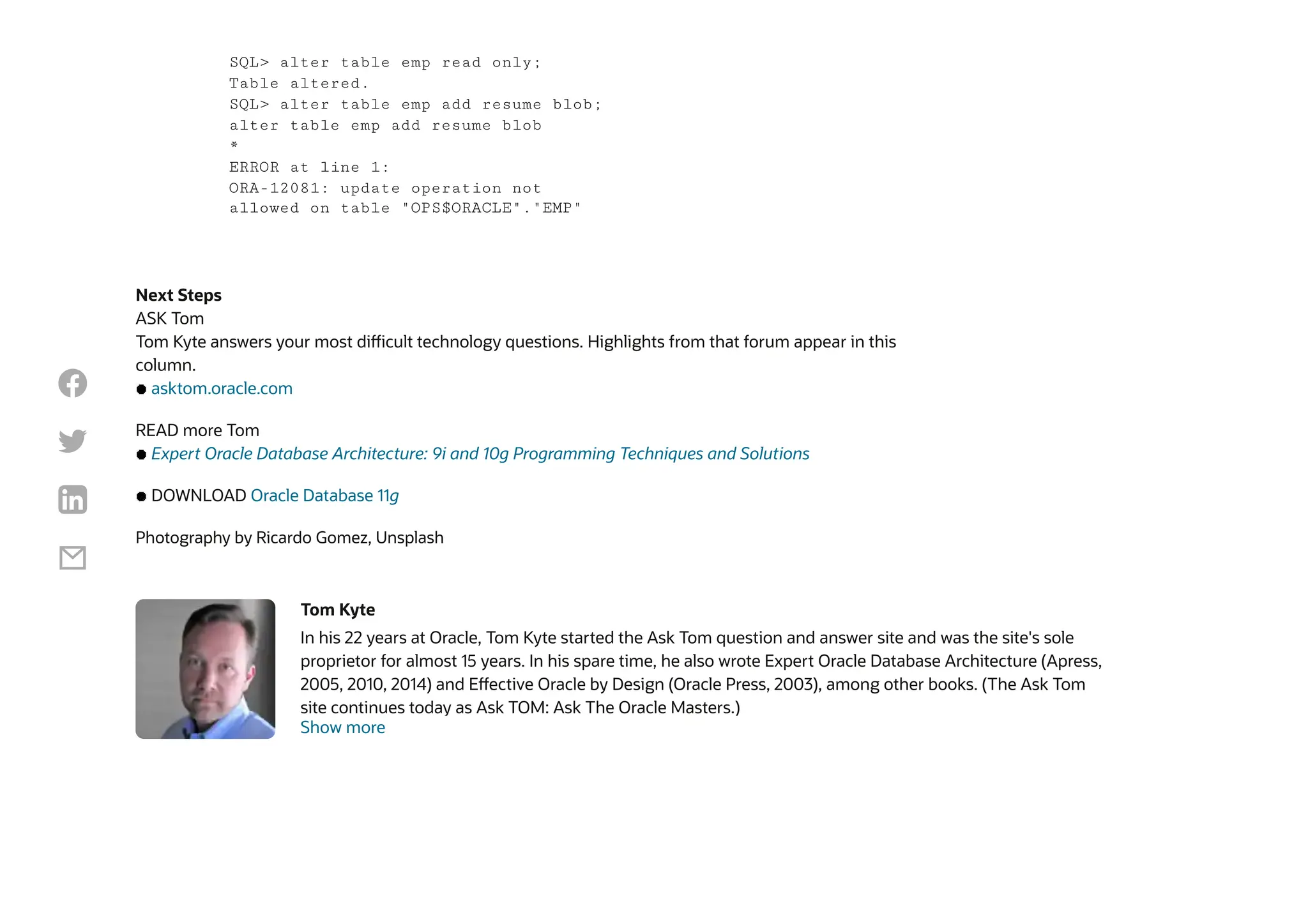

The document discusses SQL statement duplication in Oracle's v$sql, explaining how multiple entries for the same SQL statement can occur due to different user environments, bind types, and optimizer settings. It illustrates these concepts through examples, showing how distinct execution plans arise from variations in optimizations and data types used in queries. By analyzing v$sql_shared_cursor, users can gain insights into the reasons for differences in SQL execution and their impact on performance.