Smart growth aims to guide development to suitable areas and organize it into more compact, connected forms to reduce environmental impacts and support walkable communities. While smart growth has gained momentum, with many new urbanist developments and economic benefits, conventional low-density development still dominates due to restrictive zoning in most places. For smart growth to succeed, efforts must happen at both regional and local levels, as seen in programs in Maryland, Portland, and other areas.

![ensure that housing of various kinds can be pro-

duced in a range of locations. “Any corner lot in a

If Smart Growth is to single-family residential zone in Portland is enti-

tled to be converted to a duplex,” notes Robert

achieve substantial Liberty, former executive director of 1000 Friends

of Oregon. “All local governments [in the region]

results, efforts must be must authorize accessory apartments.” While sub-

urbs in many sections of the United States have

made at both regional become less dense over the years, Portland’s sub-

and local levels. urbs have become denser.

The 2000 Census found that greater Portland,

unlike most American metropolitan areas, does

not concentrate poor families in the city. People

with modest incomes were able to disperse

throughout nearly all of the Portland suburbs

because every municipality and county is required

to zone for a sizable number of apartments. In

2000, for the first time, more poor people in the

three-county area lived in the suburbs than in

Portland itself, Betsy Hammond reported in The

Oregonian. The result, in the view of Bruce Katz,

director of the Brookings’ Center on Urban and

Metropolitan Policy, is that social problems are not

compounded by concentration. Nor are the central

city and the older suburbs emptying out, dragging

down the metro area.

The center, with its MAX light-rail line and a

new streetcar line, is thriving. The light-rail line

connects towns on the east side to those on the

west. Mixed-use development has clustered close

to MAX stops like Orenco Station—a popular cen-

ter where residents can walk from home to coffee

shops, restaurants, and commuter rail.

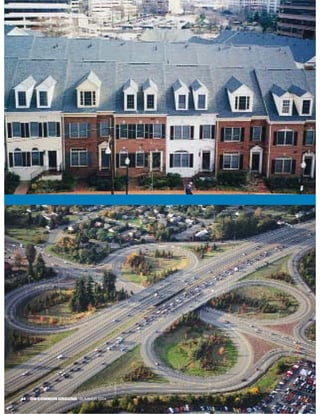

If Smart Growth is to achieve substantial

results, efforts must be made at both regional and

local levels. In metropolitan Washington, D.C., the

best development over the past 25 years owes its

growth boundaries have experienced sharply existence to the regional Metro rail system and to

escalating house prices. “In Portland, the housing local initiatives. A prime example is the profusion

supply is expanding in a fashion that corresponds of housing, offices, stores, restaurants, and ser-

very well with the population,” says Gerrit Knaap, vices within walking distance of five Metro sta-

executive director of the National Center for Smart tions in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor of Arlington

Growth Research and Education at the University County, Virginia. What had been an aging, low-

of Maryland. In part because of restrictions on density commercial road corridor in the 1960s has

outward expansion, plenty of private redevelop- become “the economic engine of Arlington

ment is occurring in the city. The population with- County,” according to James Snyder, supervisor of

in the city’s boundaries has grown to 539,000 from the county’s Planning Section. Since 1979, when

366,000 in 1980, partly through annexation but Metro opened its Orange Line in the corridor,

also through an embrace of apartments, town- 18,000 houses and apartments, 14 million square

houses, and other, denser forms of housing. feet of offices, and 21.5 million square feet of retail

Housing has been built on former parking lots, have appeared. “Things are compact and dense,”

above stores, even atop a public library. Haggard- Snyder says. The corridor, containing 7.6 percent

looking neighborhoods have improved. “There’s of the county’s land area, generates 33 percent of

no blight in Portland,” Knaap says. “That’s really its property tax revenue. It allows Arlington to set

stunning.” its property tax rate lower than other major juris-

As Smart Growth has become the norm, gov- dictions in northern Virginia.

ernments in the Portland area have taken steps to Greater Atlanta, the biggest metropolis in the

10 ON COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-9-320.jpg)

![ention zoning codes to the average person and the reaction is pre-

M dictable: a stone-faced stare, glazed eyes, a yawn. But communi-

ties across the United States are discovering that the very fabric of

their neighborhoods and towns is built on those codes—or, more accurately,

because of them. And communities are doing something about these codes.

Conventional zoning codes are fundamentally flawed, says Geoffrey

Ferrell, a principal with Geoffrey Ferrell Associates in Washington, D.C.

“Ever since the industrial years, the conventional separation-of-uses

approach has been the wrong approach to control”—to keeping unpleasant

uses away from the residential areas. “It has devolved to micromanagement

of use and density. The [built environment] that has resulted is very, very

poor about 99 percent of the time. No one’s happy with what they’ve been

given.”

Ferrell’s co-principal, Mary Madden, agrees. “That micromanagement of

uses has resulted in a huge number of unintended consequences, namely,

suburban sprawl. Everybody hates sprawl, but the builders aren’t violating

rules; they’re building exactly what the codes call for. Those codes are a

blueprint for sprawl. Under the existing conventional codes, you can’t help

but build it.”

Community frustration with conventional codes and the type of develop-

ment they spawn has driven new urbanist- and smart growth–minded plan-

ners to create new zoning codes. While these new codes go by many

names—form-based codes, new urbanist codes, TND (traditional neighbor-

hood development) ordinances, smart zoning, the SmartCode© from Miami-

based town planners Duany Plater-Zyberk & Company—they are all

designed to create places that emulate the urbanism of older, well-loved

places, while preserving rural areas and historic sites threatened by conven-

tional development.

Communities that have replaced their conventional codes with new ordi-

nances have generally reported success in the process leading up to the new

codes’ implementation, as well as favorable upturns in their real estate mar-

kets. Here are a few of the notable success stories.

nIn the 1960s, Columbia Pike was considered Arlington, Virginia’s main

street. A 3.5-mile stretch of road that runs from the Pentagon to the Arlington

County/Fairfax County border, Columbia Pike was intended to be a Metro

rail corridor. When this didn’t happen, development along the Pike stagnat-

ed and the corridor languished for 40 years. Growth occurred along the Pike,

but it was of a singular variety, says Timothy Lynch, executive director of the

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-14-320.jpg)

![The [Emmaus] code changes followed a

practical logic rather than an aesthetic one …

usually to protect the pedestrians’ safety

and enhance their experience.

the built environment that the community cared only the design review step to take if the develop-

about most: the building heights, the building er follows the SmartCode.

fronts, and the civic spaces. The code showed new “The SmartCode also eliminated mandatory

streets, new green spaces, roads, and buildings on-site parking. From a real estate perspective, a

facing the river. Different areas were coded for dif- building can now move from use to use more

ferent densities, minimum and maximum building quickly, and can change hands more quickly

heights, finished heights, parking areas, and per- because there isn’t the constraint of how much park-

centages of frontage types. ing must be included with each use.”

After the codes went into effect in June 2003, “it Mike Moore, community development director

was like a dam breaking,” says Hall. “A four- for the City of Petaluma, admits it’s a little early to

square-block theater district has been approved. A determine exactly how SmartCode is faring, but

10-acre condo project has been approved. In the likes what he sees thus far. “We had a large project

pipeline is another 10 acres of mixed-use build- in the initial stages, and in terms of the

ings: shops or workplaces on the main floor, con- SmartCode’s application, I think it has worked for

dos on top. Six downtown blocks of redevelop- that project, which is several blocks in the down-

ment are scheduled—in an area that had had very town area and includes the renovation of an exist-

little development in the last 20 years!” ing historic building and the construction of a

Fisher points to the roadblocks the Petaluma movie theater, a parking garage, some apartment

SmartCode has removed. “Two-thirds of the buildings, a mixed-use building, and a small office

approval process is gone, now,” she says. With the building.”

SmartCode—which has been approved by the Skip Sommer, a commercial REALTOR® with

Planning Commission and City Council—there’s Petaluma-based Creative Property Services/

An artist’s rendering of the North River area of the Petaluma River after potential development under the Petaluma SmartCode.

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-18-320.jpg)

![ing in a cornfield reachable only by car could rate there too much or too little low-income housing

higher for energy savings than a renovated in- nearby? What are local needs?—is likely to vary so

town building accessible by subway, foot, bike, widely that standard-setting could be very diffi-

and car. At the same time, acknowledges urban cult, Benfield said.

designer Doug Farr, the USGBC could criticize Another challenge will be to set clear standards

new urbanist and smart growth advocates for but avoid being overly rigid. “Whatever system we

neighborhood designs that fall short on minimiz- come up with will have to be flexible enough to

ing storm-water runoff, night-sky lighting, or the recognize regional variations,” Benfield said. “I

heat-island effect. personally think creativity is really important in

“We wanted to see if we could work together to the smart growth world. It’s an incredibly creative

come up with a rating system for green, smart- field, one in which new answers are being found

growth neighborhoods,” said Farr, a Chicago new almost on a daily basis. I think we need to encour-

urbanist and green architect responsible for sever- age that and whatever we do shouldn’t standard-

al LEED-rated buildings himself. Farr has been ize too much.”

representing the Congress for the New Urbanism

(CNU) in a three-way planning effort among Marketing Smart Growth in Metro Atlanta

CNU, the USGBC, and the Natural Resources As the LEED-ND panel begins to craft the new

Defense Council (NRDC), which has expertise in program, members will no doubt want to watch

both smart growth and environmental design. The developments in metro Atlanta where Sessions

collaboration has produced a 15-member panel of and three other developers are guinea pigs in a

experts that will establish rating criteria for what is LEED-like effort, with some twists. There, a col-

being called LEED-ND, for neighborhood devel- laboration between the Greater Atlanta Home

opment. Builders Association (HBA) and the Southface

“One reason to do this is to foster a positive side Energy Institute, a nonprofit

of environmentalism and reward good actors—

business people, architects, designers, REAL-

TORS® who are pursuing a path with good envi-

ronmental values,” said Kaid Benfield, NRDC’s

smart-growth guru and representative on LEED-

ND. Another is the hope that projects able to meet

the high standards will face less opposition

from neighborhood groups, or at a mini-

mum, prevent opponents from making false

claims of environmental harm. As it has

with individual buildings, a LEED standard

might also convince more developers to try

a greener approach. “Developers like pre-

dictability,” Farr said. “If you’re telling me

to do Smart Growth, give me a clear idea

what’s expected.”

Farr sees the ND designation as adding

at least two new rating categories: location

and linkage. “For location you would ask: Is

it leapfrog development or in a preferred

growth area? Is there a plan for transit or

other infrastructure? The other [linkage]

addresses neighborhood patterns—

pedestrian linkages, having something to

walk to.”

Less clear is how, or whether, to incorporate

social goals associated with Smart Growth, such

as the provision of affordable and mixed-income

housing. Those goals have an environmental com-

ponent, in that housing close to jobs and public

transportation can reduce the air and energy

impacts of long car commutes. But the context—Is

28 ON COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-27-320.jpg)

![space, but very high on transportation access and Smart Growth under Glendening. “About 75 per-

walking destinations, etc.” A jury can also cent was within PFAs [Priority Funding Areas].

better evaluate the place-making details that will But that’s not to say that everything inside was

make plans worthy of brand distinction. Smart Growth. However, on average, development

To calibrate their standards, the initial jury will outside used 10 times more land.” And State fig-

evaluate four local projects that have been praised ures show that the rate of growth in miles-driven-

as smart growth developments and that incorpo- per-person each day is slowing, she said.

rate EarthCraft houses. One of those is Sessions’ While some evidence is visible in the form of

Vickery, a suburban greenfield project in proximi- revitalized town centers and renovated neighbor-

ty to already-developed areas; another is Clark’s hood schools—and it’s clear that the land con-

Grove, a new district in the exurban city of sumption rate is slowing compared with the trend

Covington. The third is Glenwood Park, a brown- of the 1990s—better measures of progress are

field redevelopment in Atlanta, and the fourth is needed, said Frece, who left his state government

Serenbe (see map on page 28), a new village with- job to become communications director for the

in a huge swath of undeveloped Fulton County National Center for Smart Growth Research and

that is being master-planned for sustainability by a Education at the University of Maryland. Through

collaborative of land owners. “We want to test our a grant from the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy,

program against those very high-performance the center is working with the Maryland

projects to make sure we don’t miss innovation, or Department of Planning to set and measure a

that we don’t have a flaw in methodology that number of critical benchmarks.

would prevent them from qualifying,” Rader said. While the scorecard is still being formulated,

“Toward the end of summer, after we’ve made the several measures have suggested themselves,

evaluations, we’ll open it up for business.” such as: open space preserved; trends in farm

acreage; pollution in Chesapeake Bay; transit rid-

Rating Maryland’s Smart Growth Program ership; rates of biking and walking; land zoned for

Programs such as LEED and EarthCraft should mixed use; and housing supply and affordability.

make it possible to evaluate individual projects for “Unfortunately, we’re limited by what is measura-

their contribution to a metro area’s long-term ble based on what statistics are kept,” Frece said.

quality of life, and that in turn will make it easier Tregoning said she hopes any effort to measure

to build neighborhoods that mix uses and housing Smart Growth would somehow capture the most

types. Meanwhile, however, single-use sprawl important goal of all, a population that is living

development continues to be the dominant prac- happily and has hopes for an equally bright future.

tice. An increasing number of states and localities “You would want to know: Do people feel their

are adopting policies to change that. One of the access to jobs and amenities is adequate or getting

best-known states is Maryland, whose adoption of better? Do they have good choices in housing and

a Smart Growth program under Governor Parris neighborhoods at all stages of life? How do they

Glendening in the mid-1990s helped popularize feel about their quality of life?”

the term.

The Maryland program requires local govern- Conclusion

ments to designate “priority funding areas” where However we measure it, the best way to assess

most development should occur, and then limits whether neighborhoods and regions we’re build-

state funds for infrastructure and services to those ing are “smart” may be to look through the eyes of

areas. Maryland encourages redevelopment of someone living several decades hence. Will the

existing places through policies including tax neighborhoods built in the early part of this centu-

credits and a shift of school funds toward rehab- ry be as beloved and functional as those built in

bing old schools and away from new construction. the early part of the 20th century are now? Will

The state also took aggressive steps to set aside there be working farms and open vistas? Will older

open space and preserve agricultural land. “In ret- suburbs be vibrant and vital, or will they be slums?

rospect,” said John Frece, who was Glendening’s Perhaps when we can answer those and similar

special aide for Smart Growth, “one of the things questions positively we’ll at last know we’re prac-

we didn’t do, but should have, was to set specific ticing Smart Growth.

targets for what we wanted to achieve. We say we

want more walkable, livable communities, but we David A. Goldberg is the communications director for

don’t say how we’ll know we’re making progress.” Smart Growth America, a nationwide coalition based in

Washington D.C. that advocates for land-use policy

The state did measure the proportion of devel-

reform. In 2002 Goldberg was awarded a Loeb

opment occurring within priority funding areas, Fellowship at Harvard University where he studied urban

said Harriet Tregoning, who was secretary for policy.

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-33-320.jpg)

![Growth community, you have to get a variance or one can read and understand—you shouldn’t have

a conditional exception, as opposed to current to be a Ph.D. to understand them.”

zoning that encourages sprawl. It’s easy to build Larson said the Wisconsin REALTORS®

sprawl. It’s harder to build Smart Growth.” Association has launched a Quality of Life pro-

“It’s very difficult to sit on land for three years gram featuring statewide real estate and living

to go through a lengthy local permitting process. conditions surveys that will help the organization

We focused on smaller lot size, expediting the per- with its comprehensive planning efforts “by get-

mitting process within growth areas in the coun- ting into the psyche of buyers.

ty,” said Christoffel. “Rather than representing 15,000 REALTORS®,

“[The Smart Growth coalition] is the first of its we want to become the voice for over 3 million

kind in the state,” he said. “We won the 2003 State homeowners in the state,” he said.

and Local Government Affairs Award for the Best In the Pacific Northwest, the Washington

Smart Growth Program in the U.S. from the Association of REALTORS® has also created a

National Association of Home Builders. Quality of Life program focused on protecting

“We support Lancaster County’s agricultural property rights, ensuring economic vitality, pro-

history. We have permanently preserved over viding housing opportunities, preserving the envi-

50,000 acres of farmland out of about 600,000 total ronment, and building better communities.

acres,” said Christoffel. “We’ve become some of the lead players on the

Tom Larson, director of regulatory and legisla- state and local level,” said Bryan Wahl, director of

tive affairs for the Wisconsin REALTORS® government affairs for the Washington Association

Association, said their member REALTORS® got of REALTORS®. “We have really been ramping up

very proactive in Smart

Growth because “planning

is critical to protection of

the quality of life and hous-

ing market in Wisconsin.

“We saw plans only for

agricultural preservation,

only for preserving natural

resources—they were plan-

ning for areas where they

didn’t want development to

occur, but they didn’t plan

for areas where they did

want development to occur.

They didn’t look at what

the strengths and weak-

nesses were,” Larson said

of area planners. “They

didn’t plan proactively for

growth and development.”

Larson said the

Wisconsin REALTORS®

Association tells munici-

palities not to hire big, It’s easy to build sprawl. It’s

expensive planners from

far away. harder to build Smart Growth.

“Planning is about get-

ting the people to buy into

the plan. If you have a plan that nobody is going our efforts to influence local planning efforts. Our

to follow, it doesn’t make a lot of sense,” he said. concern is our ability to accommodate growth,

“Planning has to respond to local political realities especially in Washington where we have urban

and it has to be a living, breathing document that’s growth area restrictions.”

flexible. Things change. You have to allow for Wahl said the Washington Association of REAL-

change and have updates on a regular basis. TORS® has scored several key victories in the state

“Some people over-think these plans,” Larson legislature, which has supported several measures

continued. “But they should be plans that every- that encourage economic vitality, improve trans-

36 ON COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-35-320.jpg)

![portation and infrastructure financing, and

provide housing opportunities.

Wahl said Washington REALTORS® and

developers face a number of problems with

permitting processes that are difficult and

time-consuming, development regulations

that often are conflicting, and overly restric-

tive limits on use of a property.

“When you draw lines in the sand, you

have to find ways to provide for the land

capacity to accommodate that growth,” he

said. “We’ve been able to reach out and

work with organizations that typically we

weren’t on the same page with, such as

environmental [groups]. They’ve come to

see the only way we can manage land is

to provide housing of different types: mixed

use, cottage housing, planned unit develop-

ments.”

Wright and Johnson-Wright are award-winning

journalists who frequently write about Smart

Growth and sustainable communities. They live

in a restored historic home in the heart of Miami’s

Little Havana. Contact them at stevewright64

@yahoo.com.

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-36-320.jpg)

![mericans spend more from their annual household budgets coming and

A going than they do on practically anything else—and that often includes

buying the house of their dreams in the suburbs.

Surprised? You’re not alone. Look in the lane next to you.

“I’m sure a lot of people who move into a sprawling suburb don’t realize they

are inflicting more transportation costs upon themselves,” says researcher

David Goldstein of the California-based Natural Resources Defense Council

(NRDC). After studying car ownership and driving patterns in three metropoli-

tan areas, Goldstein concluded travel-related expenses often displaced the sav-

ings consumers envisioned by closing on bigger, less expensive suburban

homes. “You’ll spend more driving to and from, than paying for the home.”

Goldstein says the NRDC study draws a direct link between the amount peo-

ple drive and whether their neighborhood design includes features such as den-

HOUSING V E R S U S

TRANSPORTATION

two sides of the affordability coin

By Joanne M. Haas sity, transit access, and pedestrian and bicycle paths. “This study shows people

who live in more convenient communities are less dependent on cars.”

Similar findings surfaced in another recent survey where transportation

Researchers have costs also registered a close second in annual household expenditures,

found that sub- behind housing. “It’s all about location, location, and location,” says

researcher Robert Dunphy, senior resident fellow of Transportation and

urban sprawl Infrastructure with the Urban Land Institute in Washington, D.C.

This is why Dunphy’s study, just like Goldstein’s, stresses transportation

means consumers as one factor never to ignore when contemplating a move, no matter if it is

within a single metropolitan area or from one part of the country to another.

are spending Goldstein agrees, adding REALTORS® and consumers alike can tap a limit-

more on travel ed but growing pool of resources dedicated to helping consumers weigh

transportation and housing factors before signing on the dotted line.

than their homes

People gotta move

… and Smart Dunphy approached his study confident of one factor. “There is an extraordinary

Growth is the amount [of money] people spend on housing. We already knew that.”

Using consumer expenditure data released last year by the U.S.

real thing. Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, Dunphy’s research shows

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-44-320.jpg)

![nspired by a variety of forces—notably the dwin-

I dling supply of undeveloped land—successful

Smart Growth undertakings continue to mount.

New projects are springing up from coast to coast as

government, developers, and consumers are finding

that Smart Growth is more than a buzzword. In the

right time, place, and form, it can be the most effective

and marketable approach to development.

REALTORS® in Pasadena, California, and Arlington

County, Virginia have found this to be especially true.

Fueled by strong support from local government, devel-

opment in those two communities reflects numerous

Smart Growth principles. And buyers are eating it up.

“There’s a tremendous market for it,” said Dominic

DeFazio, a REALTOR® with Coldwell Banker in

Pasadena.

REALTOR® Tom Meyer, president of Condo 1 Inc. in

Arlington, said, “There’s been a little overbuilding with

apartments in the last couple of years, but the condo

market is extremely hot. In 15 years here, I’ve never

seen it this crazy.”

As attractive places to live within large metropolitan

areas, Pasadena and Arlington shared pressure to grow.

Yet as established communities, any vacant land had

long since disappeared. The answer was redevelop-

ment using Smart Growth principles as the building

blocks.

Arlington, one of the first communities to embrace

Smart Growth, and Pasadena, one of the latest, both

adopted infill strategies that increased density at key

locations, encouraged a mixture of uses and, most

importantly, took advantage of the arrival of rail lines.

The result? A series of vibrant urban villages where

people can live, work, and play—all without having to

battle growing congestion in their cars.

“There is a nice mix of retail, offices, and multi-

family residential at each Metro stop,” said Meyer.

“You can walk up out of a Metro station and find any-

thing you want.”

Metro is the transit network that serves the

Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. Its extension of

rail service west into Arlington County 25 years ago

gave county planners the perfect tool to prepare for the

growth they knew was coming.

“At a certain point, several decades ago, the people

in power said, ‘We know growth is coming to our area.

We know we’re going to get a Metro line here. How can

we [plan] to make sure the county doesn’t get all

clogged up with cars,’ ” explained Meyer.

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 49](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-48-320.jpg)

![within walking distance of

Mission Meridian.”

Sean’s mother, Janine,

thinks the family is making a

wise investment. “People in

California are getting tired of

[driving],” she said. “I think

this type of development will

be the rule for the next 10

years at least.”

Given the community’s

deep desire to preserve its

heritage, some Pasadena res-

idents now wonder whether

the city’s Smart Growth

approach is working too well.

“It’s raising people’s eye-

brows,” said League.

“They’re asking when is

enough enough.”

Developments in Arlington

and Pasadena are vivid

examples of the market’s

appetite for Smart Growth,

but they are not the only

“We had almost zero development for so many

years and now there’s a development on every

corner.” Maggie Navarro, REALTOR with Coldwell Banker, in Pasadena

®

stations for the Gold Line, which opened last year. ones. Post Properties can point to several Smart

The city created incentives to attract high- Growth apartment communities it has built

density, mixed-use developments to transit station around the country—including Pasadena and

sites that add urban spice to Pasadena’s predomi- Arlington but also Denver, Dallas, and Atlanta—

nantly suburban flavor. “They’re creating transit that have received similar responses.

villages ... where people can live, work, and go to “Without question, the reception has been very

a cool restaurant without leaving their neighbor- positive,” said John Mears, executive vice presi-

hood,” said Navarro. dent of the Atlanta-based development company.

The strategy has been wildly successful. “Every “People want to be closer to where they’re working

developer in Southern California is trying to build and closer to the cultural amenities of the metro-

here,” said Brian League, senior project manager politan area and not spend inordinate time in their

with the city of Pasadena. vehicles,” said Mears.

Pasadena developers find their projects in high Post Properties had specialized in building gar-

demand. “People want to be able to live close to den-style apartment homes outside the urban

shopping, close to theaters, and keep their cars at core. “They were gated communities, strictly resi-

home,” said DeFazio. “People are flocking here.” dential,” he said.

With help from his parents, recent college grad- That changed about six years ago. “It was a

uate Sean Saraf is buying a unit in Mission financial strategy as opposed to something that

Meridian Village, a mixed-use development near had a greater social conscience,” said Mears. “We

a rail station in the adjacent city of South thought if we could find well-located properties

Pasadena. “I’m looking forward to being able to within the city, it would be hard for our competi-

walk out of my loft and take the train to Los tion to find properties that would provide immedi-

Angeles ... without having to get in my car,” said ate competition to what we were building.”

the 23-year-old. “Plus there are a lot of things to do The role and scale of retail in Post Property

52 ON COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-51-320.jpg)

![developments varies from location to location. In ures because there’s a lack of a market. They’re

some, it is ancillary to the residential component. failures because they were very poorly executed.”

In others, it is an attraction in its own right. Perhaps the biggest mistake is trying to dupli-

“The destination retail, as an amenity, has been cate a successful development at a different loca-

tremendous,” said Mears. “Where we have done tion without taking into account the unique needs

that, the retail is in fact a huge selling point and of that location. “The principles of New Urbanism

clearly distinguishes us from our competitors and apply everywhere, but it takes its physical form

enables us to achieve premium [rents] for that from the characteristics of the location,” said

convenience.” Zimmerman. “It’s not a style. It’s a complete sys-

While Smart Growth advocates have plenty to tem.”

cheer about, Smart Growth remains a “woefully Looking ahead, Zimmerman says the New

small” percentage of overall development, said Urbanism expression of Smart Growth is the per-

Todd Zimmerman, co-managing director of fect response to a looming “demographic impera-

Zimmerman/Volk Associates, a development tive” in which both aging Baby Boomers and

analysis firm specializing in New Urbanism. “It’s Millennials—the generation that is currently

growing by leaps and bounds, but it’s growing off between the ages of 7 and 27—simultaneously

such a small base,” he said. seek alternatives to traditional suburban living.

Despite its many advantages, New Urbanism, “It is clearly the future,” said Zimmerman.

one element of Smart Growth, comes with no

guarantee of success, said Zimmerman. “Like any Brad Broberg is a Seattle-based freelance writer special-

other real estate development, it depends on how izing in business and development issues. His work

appears regularly in the Puget Sound Business Journal

well it’s executed and positioned,” he said. “There

and the Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce.

are several failures out there, but they’re not fail-

T he combination of New Urbanism and mass transit is

a match made in Smart Growth heaven and the knot

is being tied more and more often, said Andy Kunz.

Mission Meridian Village features 53 courtyard condo-

miniums and 14 lofts combined with 4,000-square feet of

neighborhood retail and a 324-stall parking garage—all

“Transit-oriented development (TOD) is happening in a within a short stroll of the South Pasadena Gold Line

lot of places to varying degrees,” said Kunz, director of Station.

NewUrbanism.org, a nonprofit organization that promotes Developer Michael Dieden founded CHA in 1997 with

urban living and mass transit—twin hallmarks of Smart the express purpose of pursuing TOD. “Our mission is to

Growth. build places where people can live near transit and use

TOD uses rail and bus stations as magnets to attract transit and leave their cars in the garage,” said Dieden,

high-density, mixed-use, pedestrian-friendly develop- who began planning Mission Meridian Village before it

ment, which in turn stimulates mass-transit ridership. was even certain the Gold Line was coming.

Atlanta, Portland, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Washington, Dieden’s faith did not go unrewarded. “Every unit has

D.C. are among the metropolitan areas experiencing sig- been pre-sold,” he said. “It just shows how much of a

nificant transit-oriented development, said Kunz. demand there is for this type of living.”

“It’s just about exploding around D.C.,” said Kunz. “New The key to successful TOD, said Dieden, is cooperation

housing in D.C. is selling faster than they can build it and between cities, transit agencies, and developers. That’s

most of it is within walking distance of rail stations.” what happened with Mission Meridian Village. “South

What’s exciting to see, said Kunz, is that transit agen- Pasadena is very progressive in terms of transit-oriented

cies are taking the lead in soliciting TOD proposals from development,” he said. On the other hand, Dieden

developers—not just for new stations but for existing backed away from two potential TOD projects in the Bay

ones as well. “They are looking at their parking lots and Area after he and the cities failed to agree on develop-

seeing potential [commercial] gold mines as well as a way ment strategies.

to increase ridership,” he said. “Transit development is difficult because you’re dealing

In the Los Angeles area, TOD is underway up and down with multiple public agencies, and they often have differ-

the rail lines of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. ent objectives that can conflict with the objectives a pri-

In South Pasadena, Creative Housing Associates (CHA) is vate developer is going to have,” said Dieden. “It’s not

putting the finishing touches on a showcase example. foolproof, as I have learned the hard way.”

SUMMER 2004 ON COMMON GROUND 53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-52-320.jpg)

![COMMUNITY OUTREACH GEORGIA QUALITY GROWTH PROGRAM

& EDUCATION AWARD

T GROW

AR

SM

TH

4

WIN R

NE

Georgia Department of

Community Affairs

Office of Quality Growth, State of Georgia

G

eorgia communities looking for better ways to plan for Smart Growth

can turn to the Georgia Office of Quality Growth (OQG) for advice and

planning services. Communities can request the assistance of OQG

resource teams or consultants who will evaluate local ordinances, offer direct

technical assistance, share success stories, and more. An OQG website lists

and illustrates many ways in which Smart Growth ideas can be implemented.

The OQG program, active since 2000, has two goals: (1) direct assistance

efforts to those communities that are ready to implement Smart Growth and

(2) educate communities about Smart Growth success stories in Georgia.

The program has provided $350,000 in grants to 27 communities. With

those funds, communities have, for example, created neighborhood master

plans, written infill design guidelines and development regulations, conduct-

ed corridor studies, and written new ordinances.

Program director Jim Frederick says OQG has a field staff of four who “keep

their hand on the pulse of local government so we know which [communities]

are ready to go with a Smart Growth operation.” While OQG has a marketing

program but limited resources, Frederick says, “We focus on the best

prospects, and we rely heavily on peer-to-peer interaction to publicize the

benefits of the program.”

58 ON COMMON GROUND SUMMER 2004](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/summer04-090623110510-phpapp01/85/On-Common-Ground-Summer-2004-57-320.jpg)