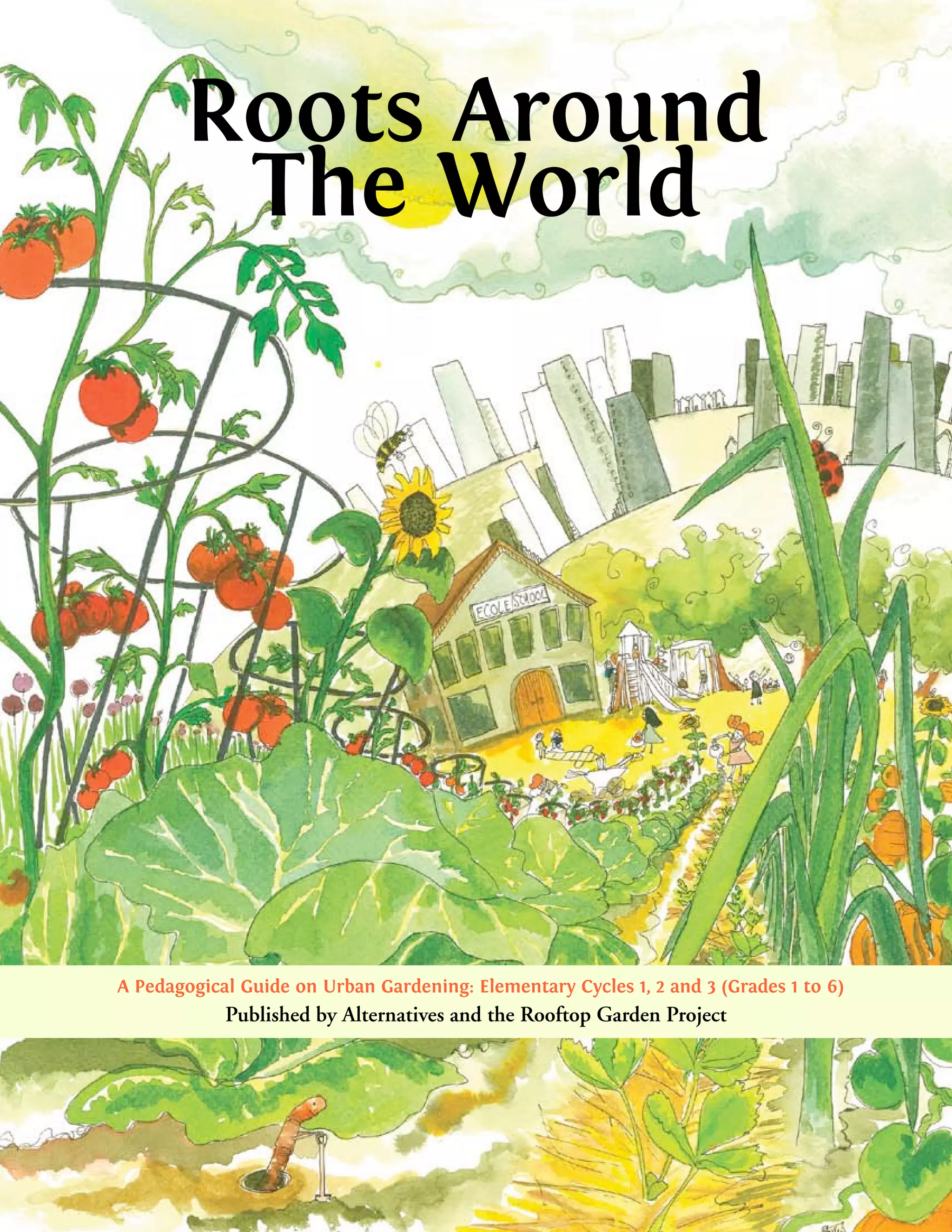

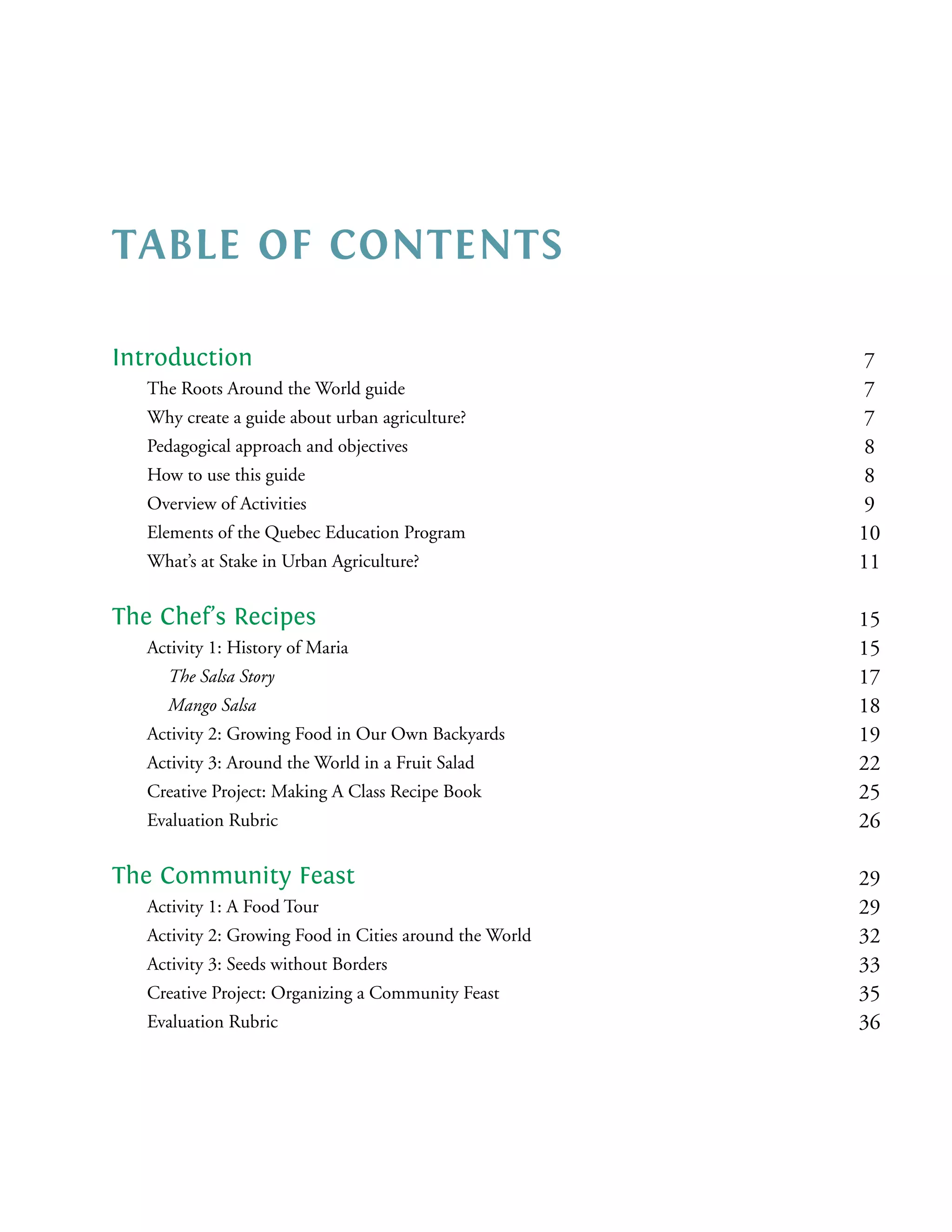

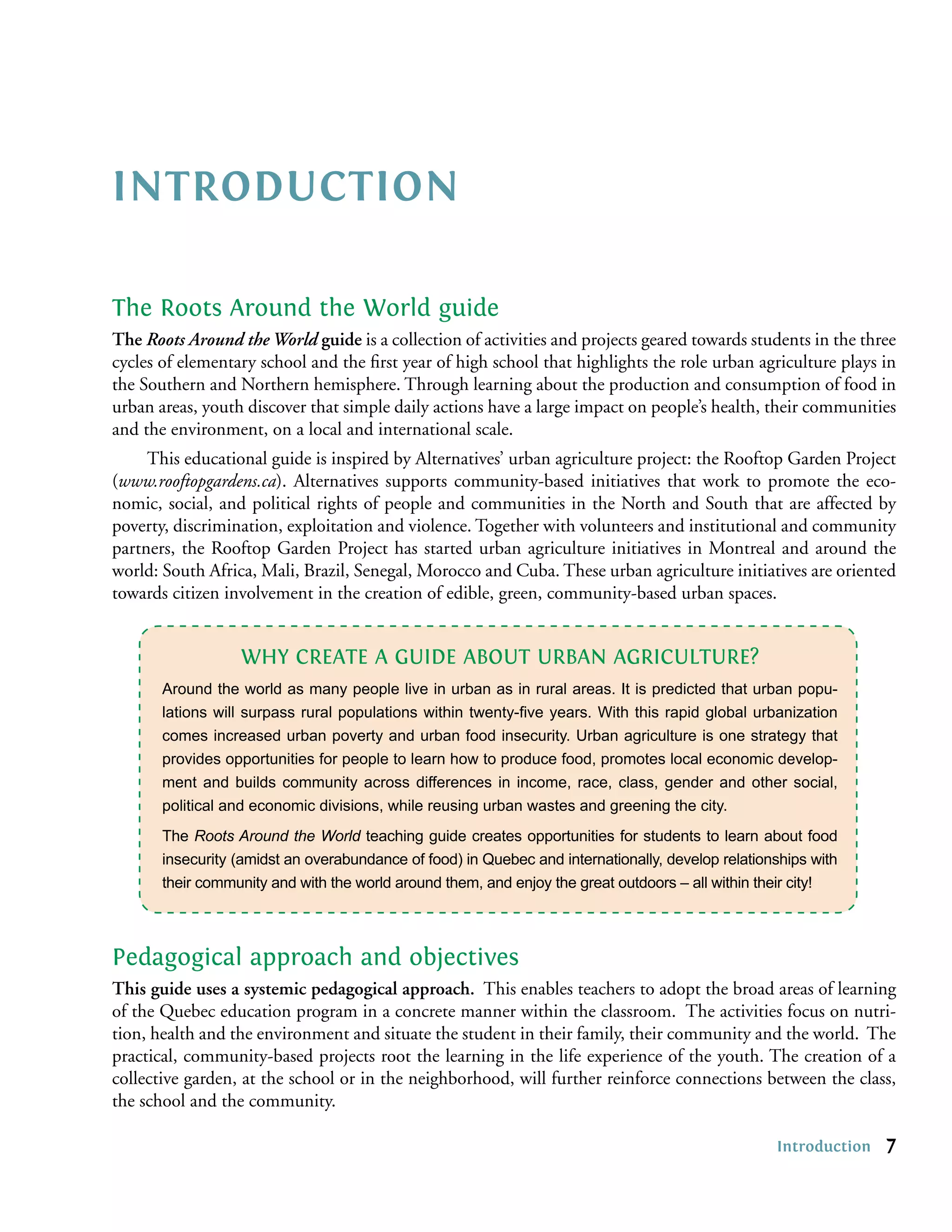

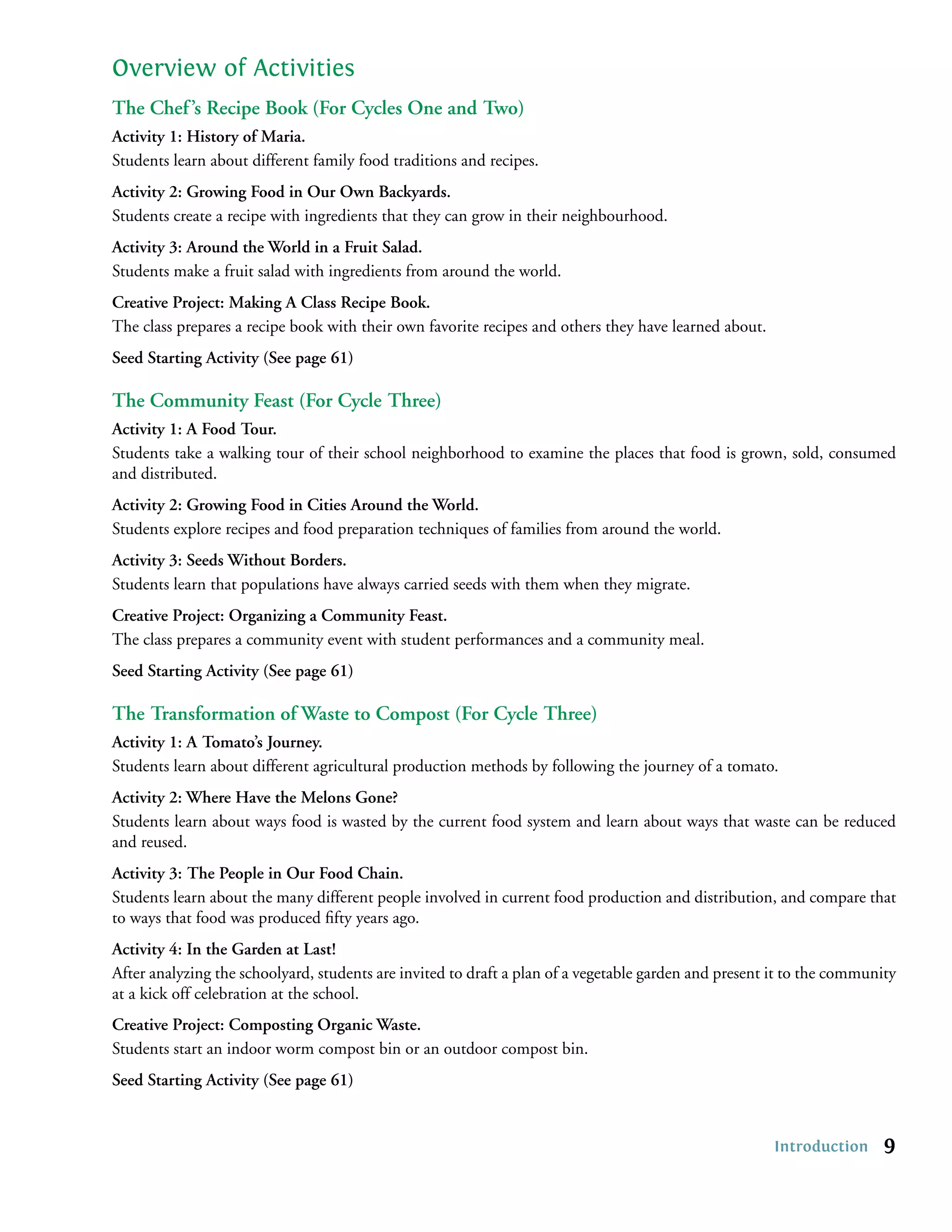

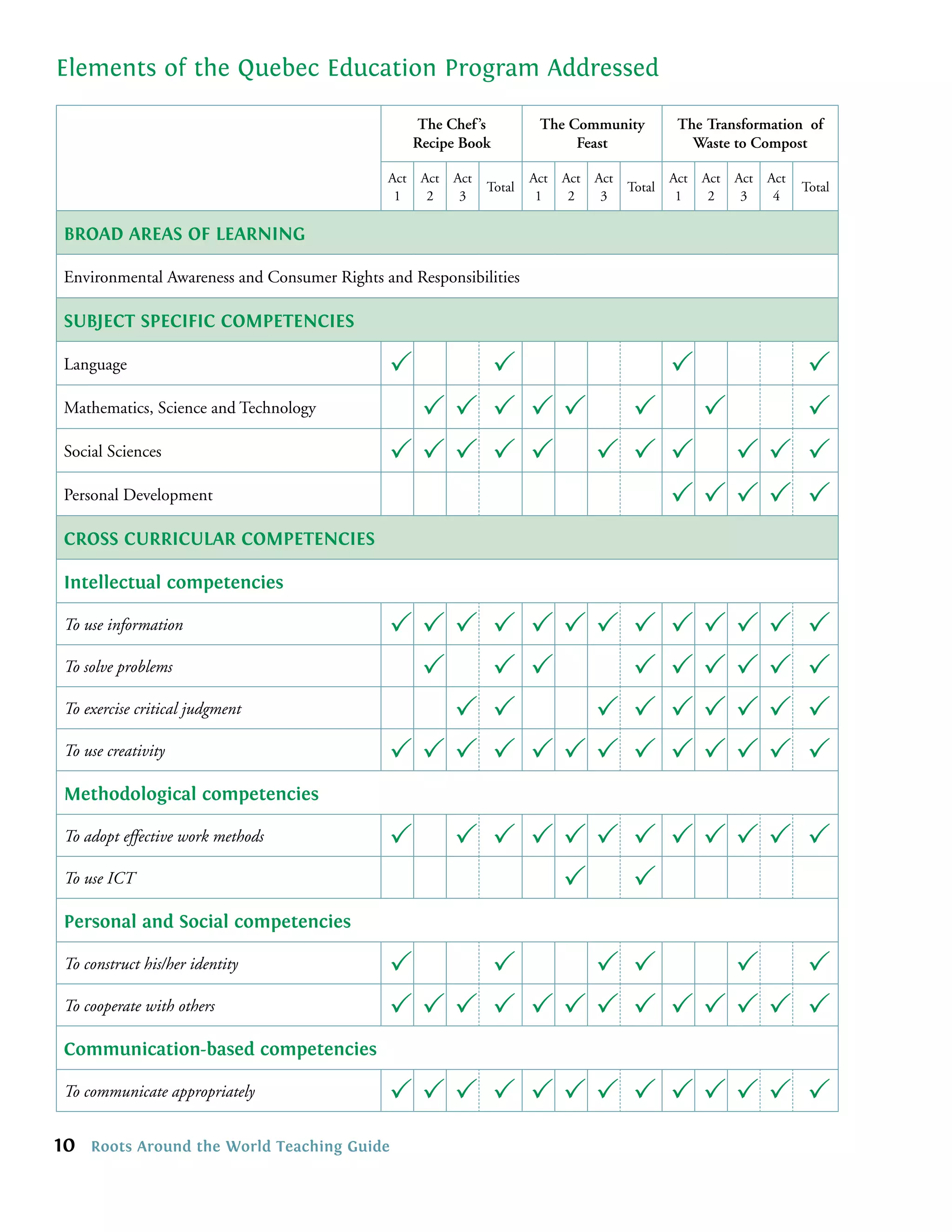

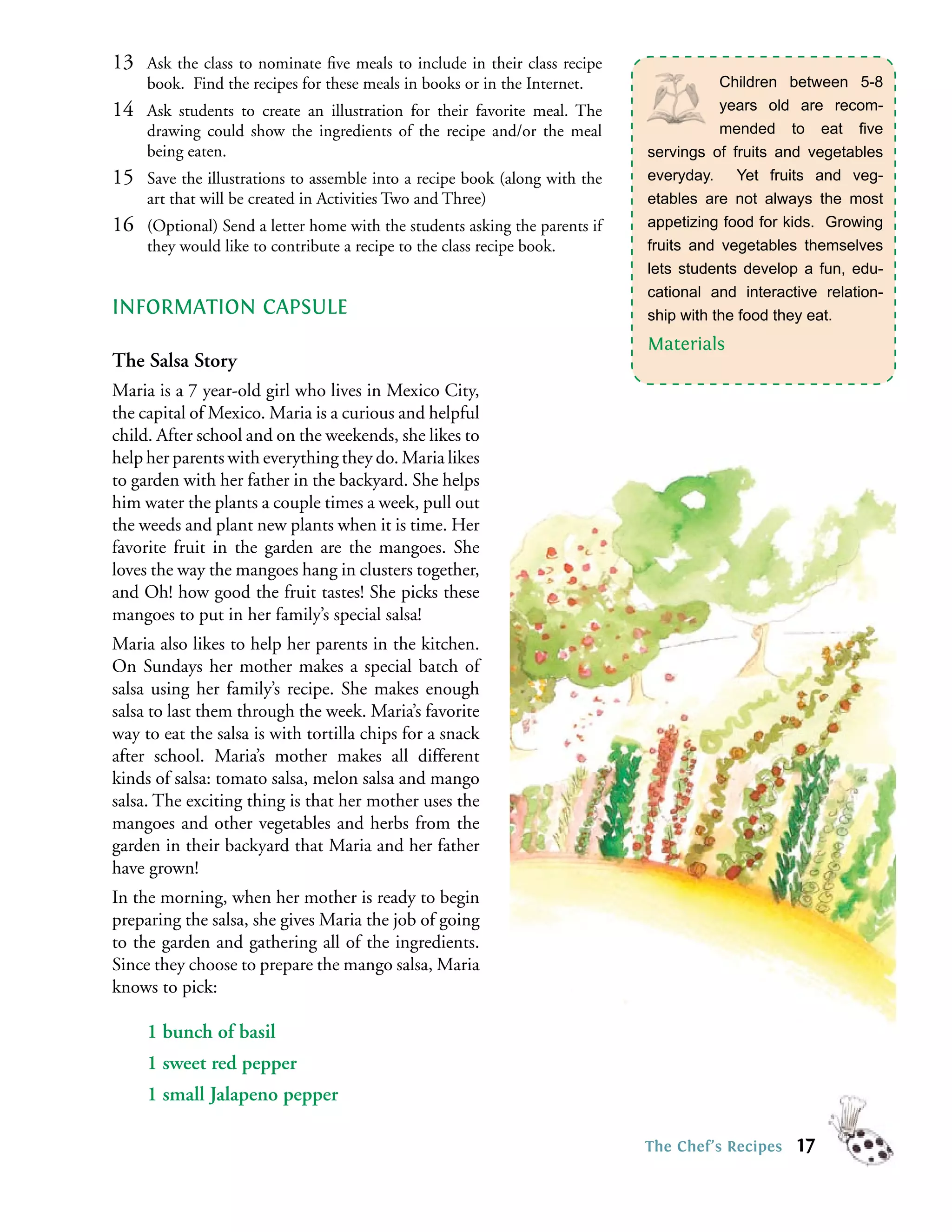

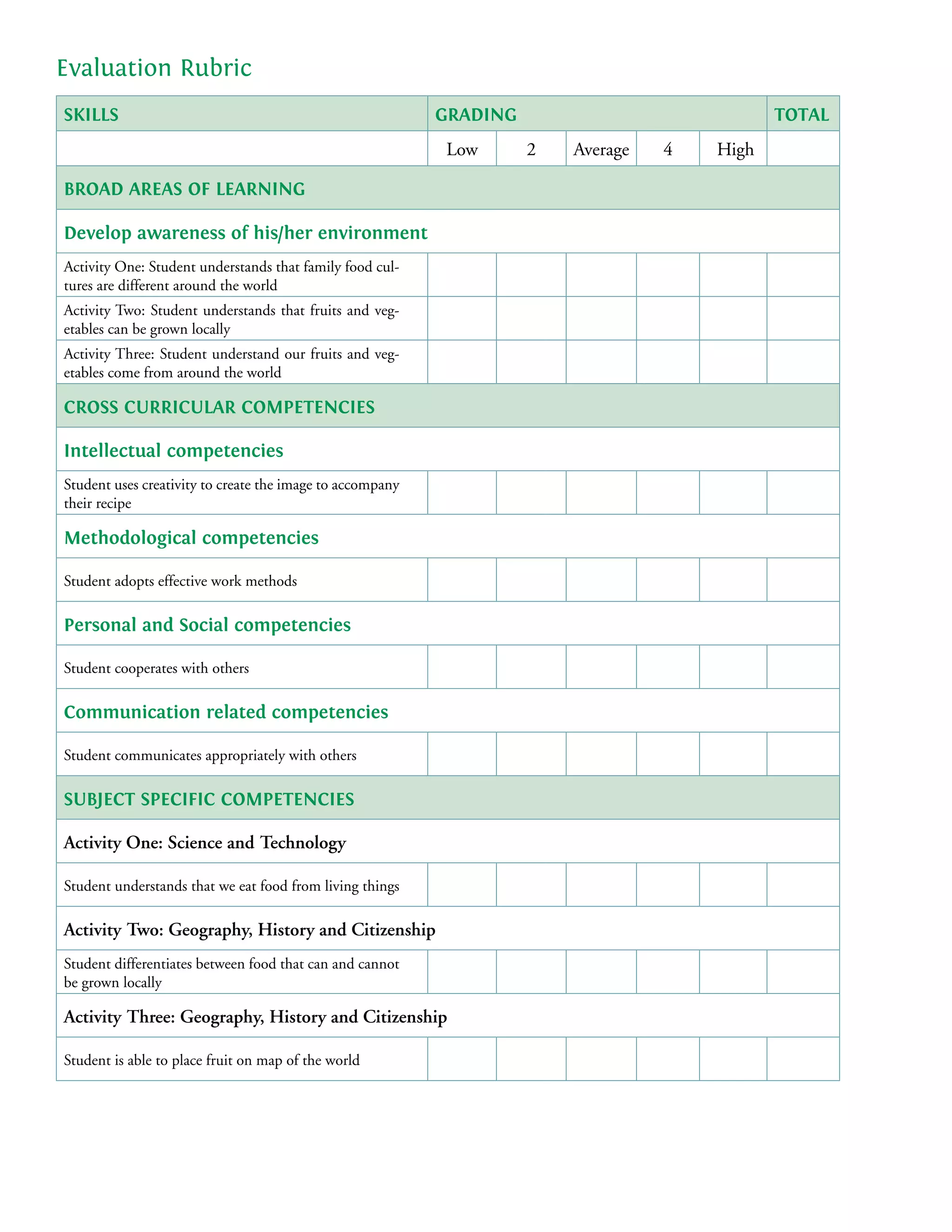

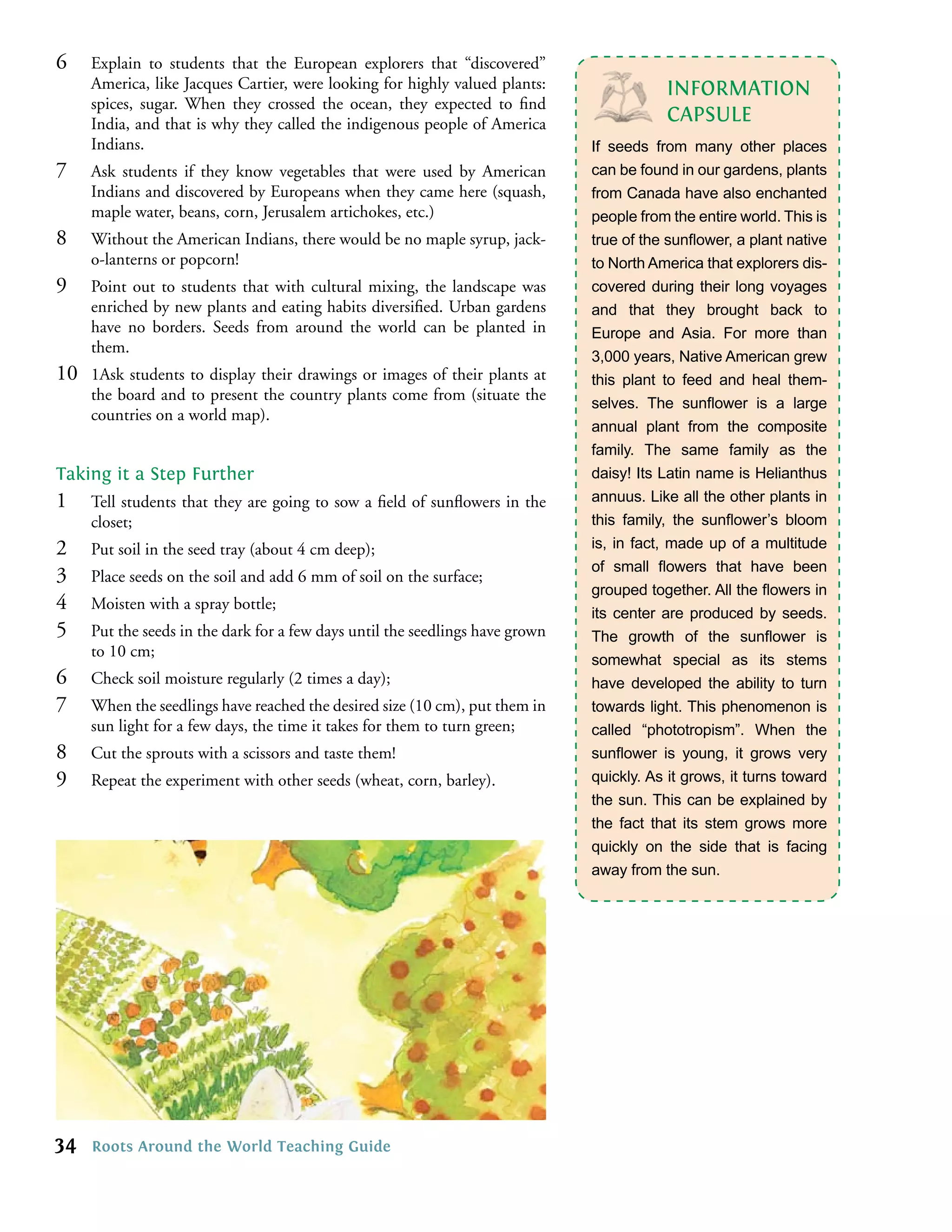

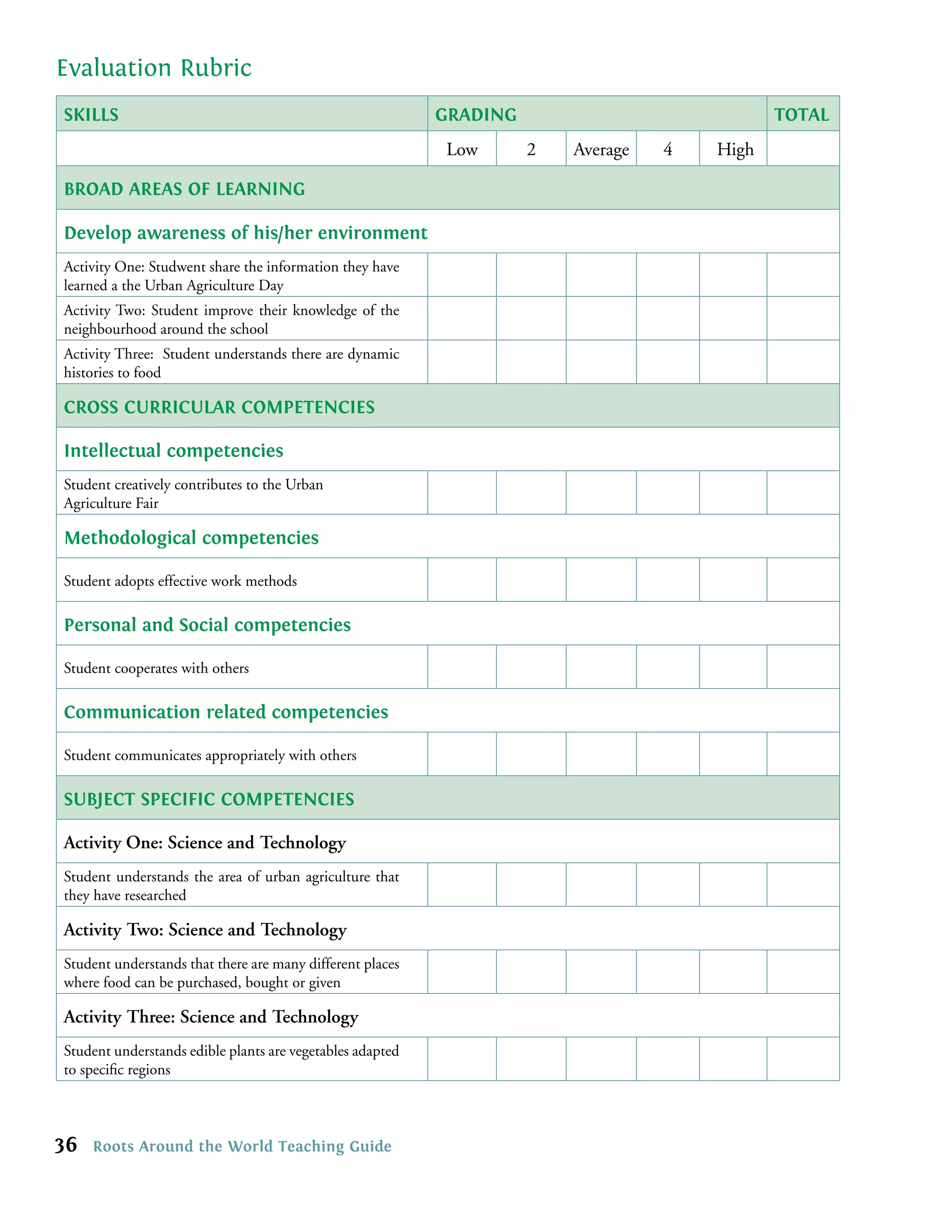

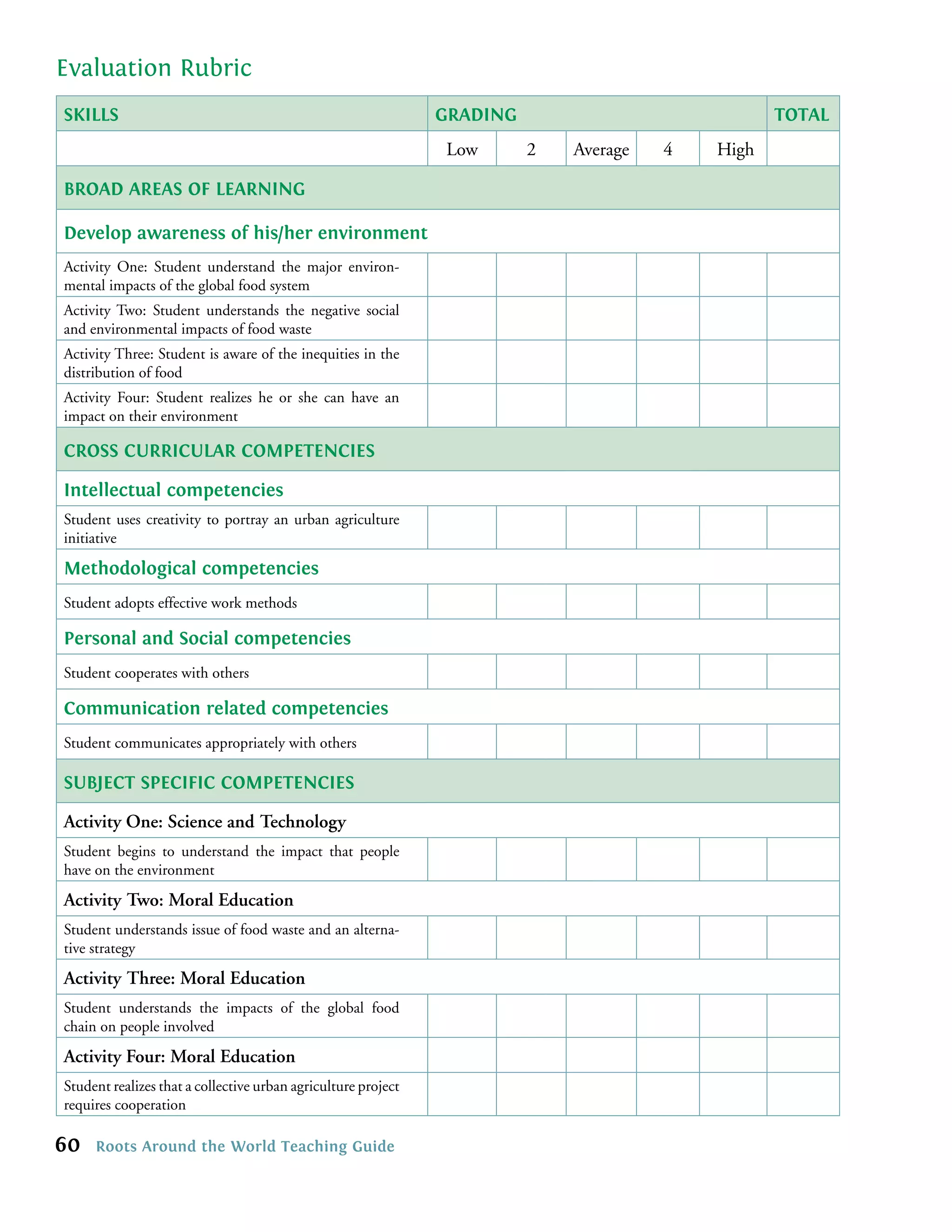

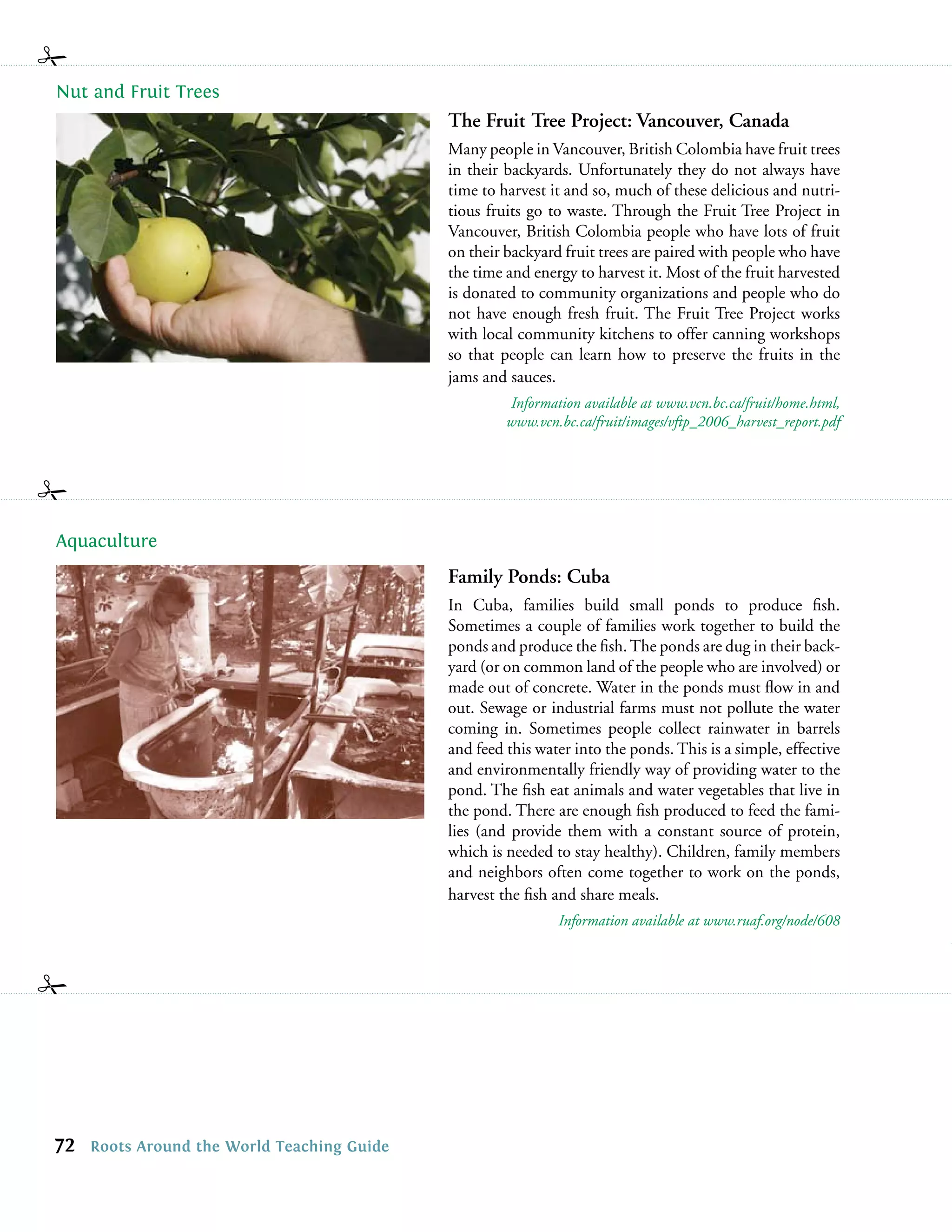

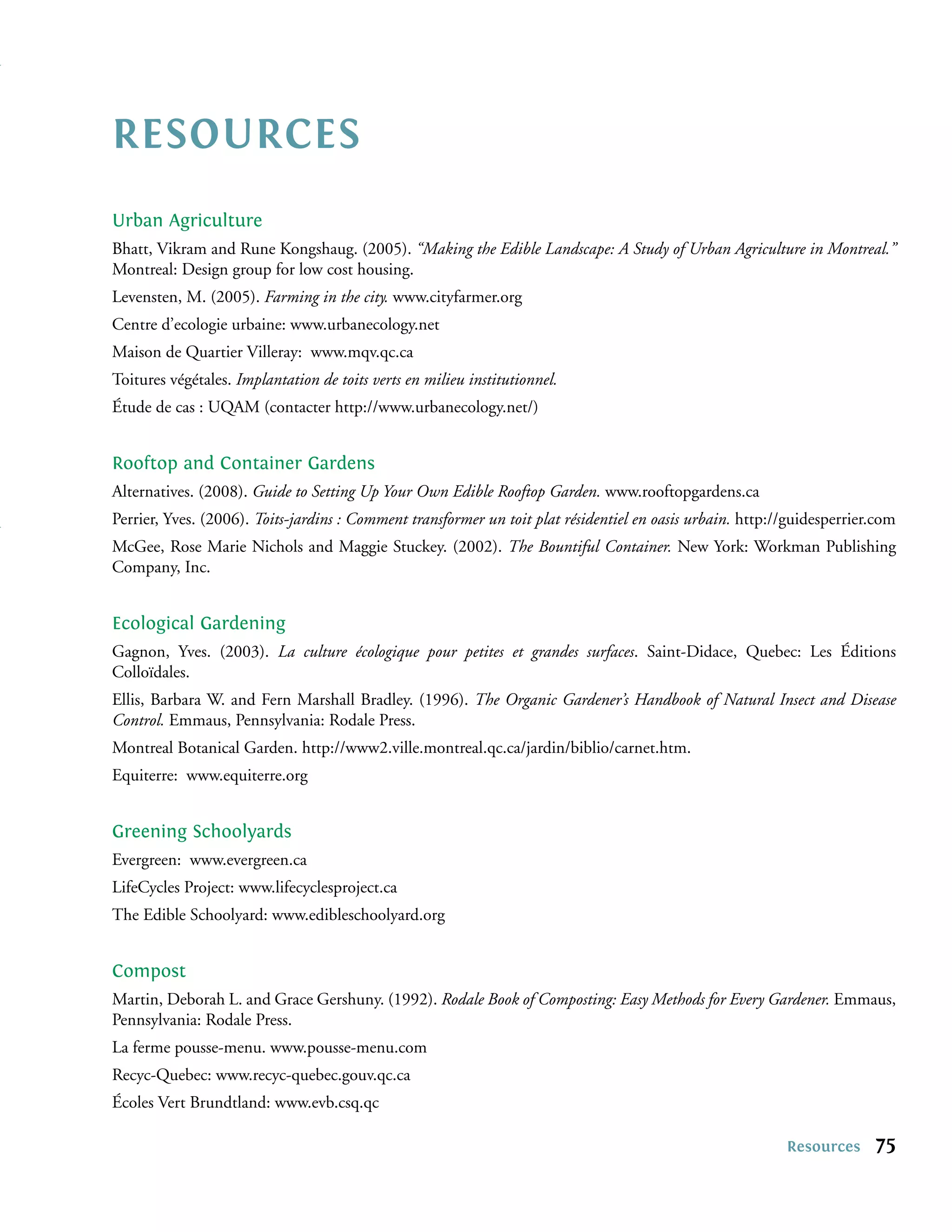

The document is a pedagogical guide created by Alternatives and the Rooftop Garden Project that provides activities for elementary school students about urban agriculture, focusing on growing food in cities and exploring its social, nutritional, and environmental benefits through practical projects and reflecting on food systems locally and globally. The guide contains 3 modules with activities and projects that build skills around food, nutrition, the environment and community.