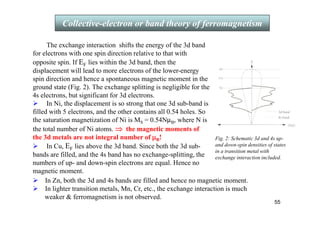

The document discusses the history and theories of magnetism, including topics such as diamagnetism, paramagnetism, and ferromagnetism, alongside their applications and underlying physical principles. It elaborates on various magnetic phenomena, including the Meissner effect in superconductors and the role of magnetic susceptibility in different materials. Additionally, the document covers quantum treatments of magnetic materials and significant contributions to the understanding of magnetism over time.

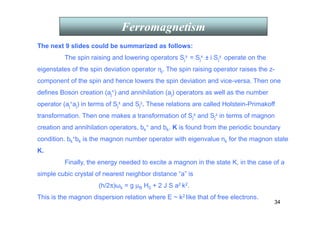

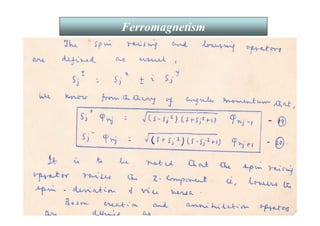

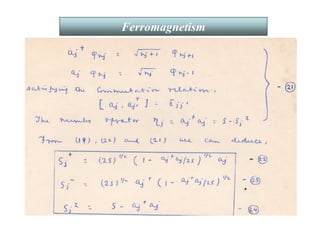

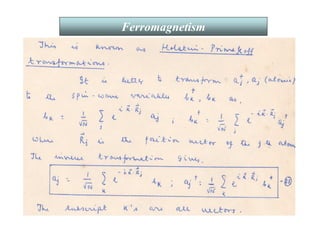

![6

Diamagnetism

QM treatment

The Hamiltonian of a charged particle in a magnetic field B is

H = (p – eA/c)2/2m + eφ, A = vector pot, φ = scalar pot, valid for both

classical QM.

K.E. is not dependent on B, so it is unlikely that A enters H. But

p = pkin + pfield = mV + eA/c (Kittel, App. G, P: 654)

K.E. = (mV)2 /2m = (p – eA/c)2/2m, where B = ∇

∇

∇

∇ X A.

So, B-field-dependent part of H is ieh/4πmc[∇

∇

∇

∇. A+ A. ∇

∇

∇

∇ ] + e2 A2/2mc2.(1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-6-320.jpg)

![7

Diamagnetism

QM treatment

χ = LtH→0 (dM/dH) = - (Ne2Zr2av )/6mc2 independent of T.

M = - ∂E’/∂B = - (Ne2Zr2av )/6mc2 B for N atoms/volume with atomic no. Z.

Since B = H for non-magnetic materials

If B is uniform and II z-axis, AX = - ½ y B, AY = ½ x B, and AZ = 0.

So, (1) becomes H =(e/2mc) B [ih/2π(x ∂/∂y - y ∂/∂x)] + e2B2/8mc2(x2 + y2).

↓ ↓

LZ ⇒ Orbital PM; E’ = e2B2/12mc2 r2

by 1st order

perturbation theory.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-7-320.jpg)

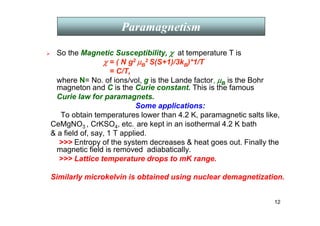

![11

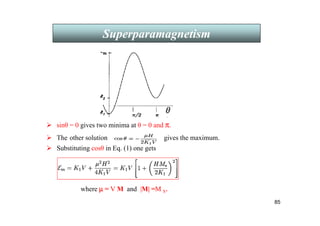

In this m vs. H/T plot

paramagnetic saturation is

observed only at very high H low

T, i.e., x 1 when coth x →

→

→

→ 1 and

m →

→

→

→ NgµBS

At 4 K 1tesla, m ~ 14 % of its

saturation value.

For ordinary temperatures like 300

K 1 T field, x 1. Then coth x

→

→

→

→ 1/x + x/3 and so

NgµB.

Paramagnetism

0 2 4 6 8 10

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

S=3/2 FOR Cr3++

Magnetic

Moments

Magnetic Field/Temperature(B/T)

H

T

k

S

S

g

m

B

B

+

→

3

)

1

(

µ

Thus m varies linearly with field.

m = Ngµ

µ

µ

µBS [coth X- 1/X] = L(X) = Langevin function when S →

→

→

→ ∞

∞

∞

∞ with X = Sx.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-11-320.jpg)

![13

Paramagnetism

Fascinating magnetic properties, also quite complex in nature:

Ce58: [Xe] 4f2 5d0 6s2, Ce3+ = [Xe] 4f1 5d0 since 6s2 and 4f1 removed

Yb70: [Xe] 4f14 5d0 6s2, Yb3+

= [Xe] 4f13 5d0 since 6s2 and 4f1 removed

Note: [Xe] = [Kr] 4d10 5s2 5p6.

In trivalent ions the outermost shells are identical 5s2 5p6 like neutral Xe.

In La (just before RE) 4f is empty, Ce+++ has one 4f electron, this

number increases to 13 for Yb and 4f14 at Lu, the radii contracting from 1.11

Å (Ce) to 0.94 Å (Yb) → Lanthanide Contraction. The number of 4f

electrons compacted in the inner shell is what determines their magnetic

properties. The atoms have a (2J+1)-fold degenerate ground state which is

lifted by a magnetic field.

Rare–earth ions

In a Curie PM

=

( )

T

Np

T

C

T

g

J

NJ

B

B

B

κ

µ

κ

µ

χ β

3

3

1

2

2

2

2

=

=

+

= , p = effective Bohr Magnetron number

.

( )

[ ]

1

+

J

J

g

)

1

(

2

)

1

(

)

1

(

)

1

(

1

+

+

−

+

+

+

+

=

J

J

L

L

S

S

J

J

, g = Lande factor

‘p’ calculated from above for the +

3

RE ions using Hund’s rule agrees

very well with experimental values except for

3+

Eu +

3

Sm .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-13-320.jpg)

![16

Paramagnetism

Explanation of 3rd rule:

Consequence of the sign of the spin-orbit interaction. For a single

electron, energy is lowest when S is antiparallel to L (L.S = - ve). But

the low energy pairs ml and ms are progressively used up as one adds

electrons to the shell. By PEP, when the shell is more than half full the

state of lowest energy necessarily has the S ║ L.

Examples of rule 3:

Ce3+ = [Xe] 4f1 5s2 5p6 since 6s2 and 4f1 removed. Similarly Pr3+ = [Xe]

4f2 5s2 5p6. Nd3+, Pm3+, Sm3+, Eu3+,Gd3+,Tb3+, Dy3+, Ho3+,Er3+ ,Tm3+,Yb3+

have 4f3 to 4f13. Take Ce3+: It has one 4f electron, an f electron has l = 3,

s = ½, 4f shell is less than half full (full shell has 14 electrons), by third

rule = J = L – S = L - 1/2 = 5/2.

J

s

L

1

2 +

2

/

5

2

F

+

3

Pr

Spectroscopic notation ⇒

⇒

⇒

⇒ [L = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 are S, P, D, F, G, H, I].

has 2 ‘4f’ electrons: s = 1, l = 3. Both cannot have ml = 3 (PEP),

so max. L is not 6 but 5. J = L – S = 5 -1 = 4. ⇒

⇒

⇒

⇒ 3H4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-16-320.jpg)

![17

Paramagnetism

Exactly ½ full 4f shell: : has 7 ’4f’ electrons; s = 7/2, L = 0, J = 7/2

+

3

Nd 2

/

9

4

I

+

3

Pm 4

5

I

has 3 ‘4f’ electrons: s = 3/2, L = 6 , J = 6 - 3/2 = 9/2 ⇒

has 4 ‘4f’ electrons: s = 2, L = 6, J = L - S = 4 ⇒

+

3

Gd

2

/

7

8

S

⇒

+

3

Ho ↑

↓ 8

5

I

4f shell is more than half full: has 10 ‘4f’ electrons: 7 will be ,

3 will be . S = 2, L = 6 [3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3] ; J = 6 + 2 = 8 ⇒ and so on.

Note: 4f shell is well within the inner core (localized) surrounded by 5s2, 5p6, and

6s2 so almost unaffected by crystal field (CF).

3d transition element ions

3d transition element ions, being in the outermost shell, are affected by strongly

inhomogeneous electric field, called the “crystal field” (CF) of neighboring ions in

a real crystal. L-S coupling breaks, so states are not specified by J. (2L + 1)

degenerate levels for the free ions may split by the CF and L is often quenched.

“p” calculated from J gives total disagreement with experiments.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-17-320.jpg)

![21

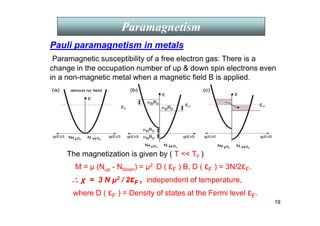

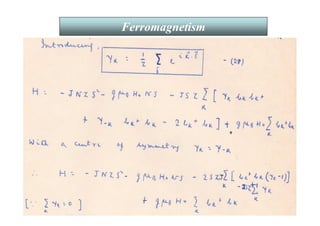

Weiss proposed that:

i) Below TC spontaneously magnetized domains, randomly oriented

give M ~ 0 at H=0. A small H0 produces domain growth with M || H0.

ii) A very strong “molecular field”, HE of unknown origin aligns the

atomic moments within a domain.

Taking alignment energy ~ thermal energy below Tc,

For Fe: HE = kBTC / µ ~ 107 gauss ~ 103 T !!!

Ed-d ~ [µ1. µ2 - (µ1.r12) (µ2.r12)]/4πε0r3.

Classical dipole-dipole interaction gives a field of ~ 0.1 T only

is anisotropic but ferromagnetic anisotropy is only a second

order effect. So ???

Weiss postulated that HE = λM, where λ is the molecular field

parameter and M is the saturation magnetization.

Ferromagnetism

Weiss’ “molecular field” theory](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-21-320.jpg)

![22

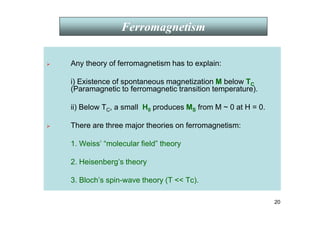

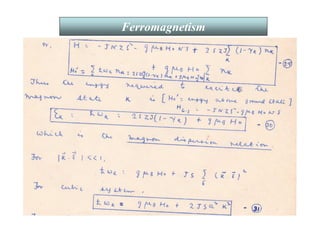

Curie-Weiss law

Curie theory of paramagnetism gave

M = [( N g2 µB

2 S(S+1)/3kB)*1/T]*H

= (C/T)*H.

Replacing H by H0 + λM we get

M = CH0/(T-Cλ)

∴

∴

∴

∴ χ

χ

χ

χ = C/(T-T*C ),

where T*C = Cλ = paramagnetic Curie

temperature.

Putting g ~ 2, S = 1, M = 1700 emu/g

one gets λ = 5000 HE = 103 T for Fe.

This theory fails to explain χ (T) for

T T*C .

Ferromagnetism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-22-320.jpg)

![26

Heisenberg’s Theory (Exchange effect)

2

1

2

1

2

2

*

1

*

)

(

)

(

)

(

)

( r

d

r

d

r

u

r

u

r

r

e

r

u

r

u

J i

j

j

i

j

i

ij

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

r

∫ −

=

Ferromagnetism

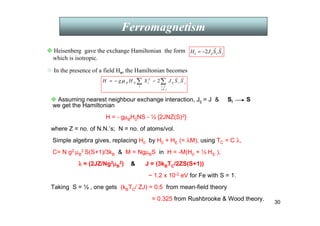

Heisenberg found the origin of Weiss’ “molecular field” in the “quantum

mechanical exchange effect”, which is basically electrical in nature.

Electron spins on the same or neighboring atoms tend to be coupled by

the exchange effect – a consequence of Pauli’s Exclusion Principle. If ui

and uj are the two wave-functions into which we “put 2 electrons”, there

are two types of states that we can construct according to their having

antiparallel or parallel spins. These are

Ψ (r1, r2) =1/√2 [ui (r1) uj (r2) ± uj (r1) ui (r2)] where

± correspond to space symmetric/antisymmetric (spin singlet, S = 0/spin

triplet, S = 1) states.

Singlet: spin anisymmetric: S = 0: (↑↓ - ↓↑)/ √2 , m = 0.

Triplet: spin symmetric: S = 1: ↑↑ m = 1; ↓↓ m = -1;

(↑↓ + ↓↑)/ √2 , m = 0.

Also, if you exchange the electrons between the two states, i.e.,

interchange r1 and r2, Ψ(-) changes sign but Ψ(+) remains the same. If

the two electrons have the same spin(║), they cannot occupy the same

r. Thus Ψ(-) = 0 if r1 = r2. Now if you calculate the average of the

Coulomb energy e2/│r12 │in these two states we find them different by

which is the “exchange integral”.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-26-320.jpg)

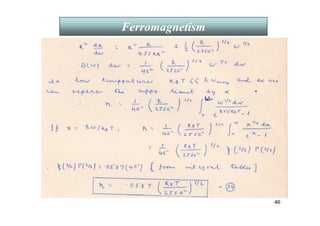

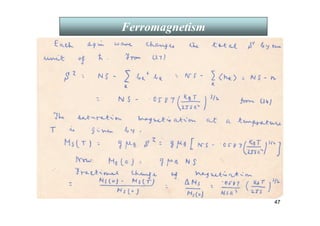

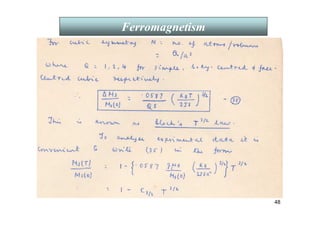

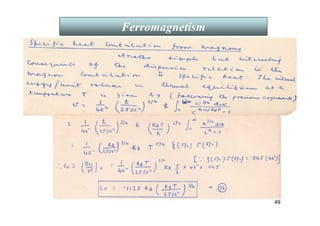

![51

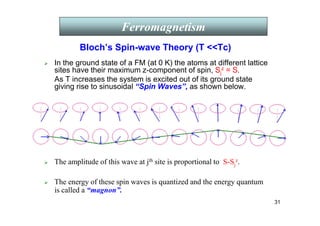

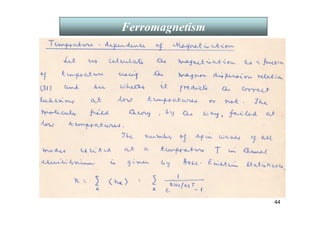

Using the spin-wave dispersion relation for a cubic

system

(h/2π)ωk = gµBH0 + 2Jsa2k2,

one calculates the number of magnons, n in thermal

equilibrium at temperature T to be proportional to T3/2

and hence

M(T) = M(0) [1+ AZ{3/2, Tg/T} T3/2 + BZ {5/2,Tg/T}T5/2].

This is the famous Bloch’s T3/2 .

Similarly specific heat contribution of magnons is also

~ T3/2.

Both are in very good agreement with experiments.

Ferromagnetism

Spontaneous magnetization,

MS of a ferromagnet as a

function of reduced

temperature T/TC.

Bloch’s T3/2 law holds only

for T/TC 1.

Ferromagnetism

Ferromagnetism

Summary of spin-wave theory](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-51-320.jpg)

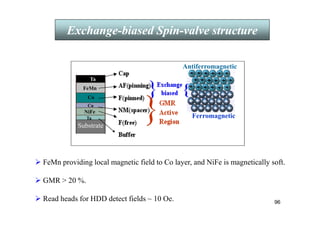

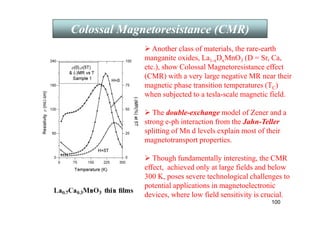

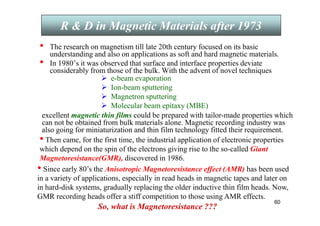

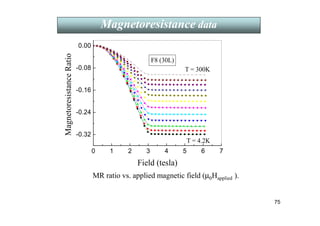

![62

• RKKY interaction ~ cos(2kf r)/(2kf r)3 .

• Established by experiments on light scattering by spin waves.

[ P. Grünberg et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2442(1986).]

At high fields the spins align

with the field (saturating at Hsat)

and the resistance is reduced.

Magnetoresistance is negative!

At low fields the interlayer antiferromgnetic

coupling causes the spins in adjacent layers

to be antiparallel and the resistance is high

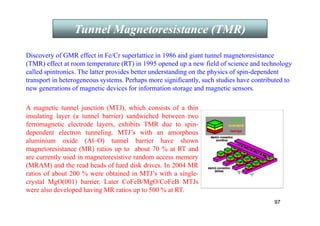

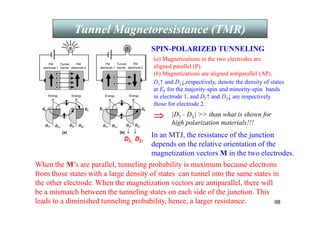

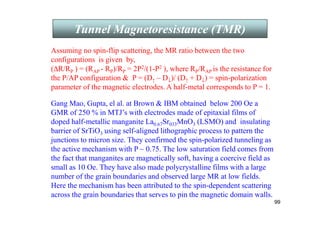

III. Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR)

Fe-Cr is a lattice matched pair : Exchange coupling of ferromagnetic Fe

layers through Cr spacers gives rise to a negative giant magnetoresistance

(GMR) with the application of a magnetic field.

Introduction

Magnetoresistance](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-62-320.jpg)

![63

Fe-Cr

Magnetoresistance is defined by

.

%

100

)

,

0

(

)

,

0

(

)

,

(

×

−

=

T

T

T

H

MR

ρ

ρ

ρ

(1)

Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR)

Giant Magnetoresistance (GMR)

Bulk scattering Interface scattering

[ Magnetic Multilayers and Giant Magnetoresistance, Ed. by Uwe Hartmann,

Springer Series in Surface Sciences, Vol. 37, Berlin (1999).]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-63-320.jpg)

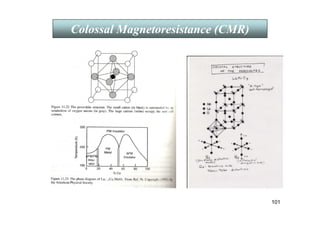

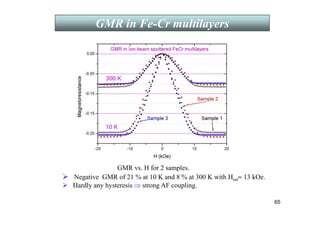

![64

Sample structure

Cr(t Å)

30 bi-layers

of Fe/Cr

Sample details

Si/Cr(50Å)/[Fe(20Å)/Cr(tÅ)]×30/Cr((50-t)Å)

Varying Cr thickness t = 6, 8, 10, 12, and 14 Å

Cr ( 50-t )Å

Cr 50 Å

Si Substrate

Fe/Cr multilayers prepared by ion-beam sputtering technique.

Ar and Xe ions were used.

Beam current 20 mA /30 mA and energy 900eV/1100eV.

Fe(20 Å)

bi-layer

GMR in Fe-Cr multilayers](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-64-320.jpg)

![67

RS ( Extra-ordinary or spontaneous Hall constant ) :

a) Classical Smit asymmetric scattering(AS).

b) Non-classical transport (side-jump).

Boltzmann Eq. is correct to the lowest order in («1) (τ = relaxation time),

true for pure metals and dilute alloys at low temperatures.

RS caused by AS of electrons by impurities in the presence of spin-orbit

interaction in a ferromagnet .

Boltzmann Eq.

a) Classical Smit asymmetric scattering (AS)

,

where [s] = relaxation frequency tensor ~ impurity concentration.

Off-diagonal elements describe AS proportional to M.

Diagonal elements give Ohmic ρ.

Boundary condition: jy= 0 ⇒

⇒

⇒

⇒ ρH and ρ.

RS = a ρ.

[L. Berger, Phys. Rev. 177, 790(1969).]

F

E

τ

h

[ ]j

s

e

m

B

j

E

en

dt

p

d r

r

r

r

r

−

×

+

=

Introduction (theory)

Hall Effect](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-67-320.jpg)

![68

b) Non-classical transport (side-jump mechanism)

is not small ⇒ Concentrated and disordered alloys, high temperatures.

[R. Karplus and J. M. Luttinger, Phys. Rev. 95, 1154 (1954).]

Calculation: Free electron plane wave (e i kx ) is scattered by a short-range

square well impurity potential

with V(r) = 0 for r R V(r) = V0 for r R. Using Born approx. one finds

a side-wise displacement of the wave-packet ∆y ~ 0.1-0.2 nm (side-jump).

F

E

τ

h

Z

Z S

L

r

V

r

c

m

r

V

m

H

∂

∂

+

+

∇

−

=

1

2

1

)

(

2 2

2

2

2

h

Transport theory for arbitrary ωcτ = e B τ / m, ωc= cyclotron frequency gives

ρH = R0Bz + µ0RSM , where RS = b ρ2.

Combining Eqs.(3) (4) for the most general case one gets

RS = a ρ + b ρ2 .

[L. Berger and G. Bergmann , in the Hall effect and its applications, edited by C. L.

Chien and C. R. Westgate (Plenum, New York , 1980), p.55 and references therein.]

Introduction (theory)

Hall Effect](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-68-320.jpg)

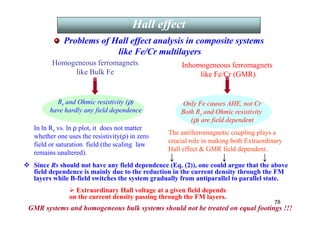

![t = 0 t = 0

t « 0

t » 0

t « 0

Y

Y

t » 0

δ

y

S

a) b)

Skew scattering Side jump scattering

[L. Berger and G. Bergmann , in the Hall effect and its applications, edited by C. L. Chien

and C. R. Westgate (Plenum, New York , 1980), p.55 and references therein.]

Hall Effect

69](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-69-320.jpg)

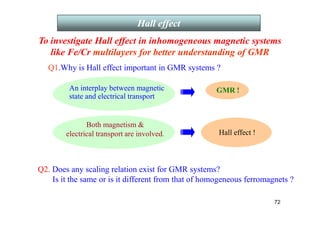

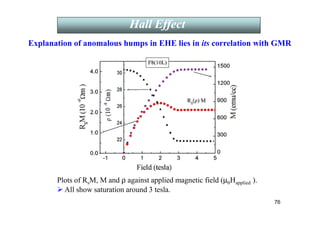

![Hall effect in GMR multilayers

All the theories discussed earlier are valid for homogeneous ferromagnets.

Scaling law is valid only in the local limit; the mean free path λ « d, the

layer thickness. It is invalid in the long mean free path limit; λ » d.

Zhang had shown the failure of scaling law in composite magnetic-

nonmagnetic systems:

The standard boundary condition used for calculating ρH, jy(z) = 0, is not

valid here for all z, but jy(z), integrated over z, is zero.

The two-point local Hall conductivity is given by

σyx (z, z') ∝ (m λSO MZ σCIP (z, z'))/τ(z), (3)

where σCIP (z, z') is the CIP two-point Ohmic conductivity.

To get σyx, integrate σyx (z, z') over z and z' and sum over the

spin variables.

[S. Zhang , Phys. Rev. B 51 , 3632(1995).]

Theory of Hall effect in inhomogeneous ferromagnets

Theory of Hall effect in inhomogeneous ferromagnets

70](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-70-320.jpg)

![0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

0.0

1.5

3.0

4.5

6.0

7.5

9.0

Peak position

T = 300K

T = 4.2K

F8 (30L)

Hall

Resistivity

(10

-9

Ω

m)

Field (tesla)

Hall resistivity (ρH) vs. applied magnetic field (µ0Happlied ).

Q 3. Why do the humps appear in the EHE just before the

saturation field in these GMR systems?

Hall Effect data

Hall Effect data

In Hall geometry B = µ0[Happlied+ (1-N) M], N=demagnetization factor.

74](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-74-320.jpg)

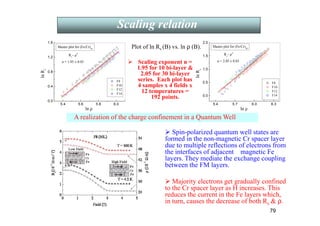

![5.6 5.8 6.0 6.2

0.0

0.3

0.6

0.9

1.2

1.5

F10(30L)

n = 3.45 ± 0.11

F10(10L)

n = 3.07 ± 0.04

Rs

~ ρ

n

ln

R

s

ln ρ (at B = 0)

Plot of ln Rs vs. ln ρ (ρ being the resistivity at B = 0).

Q 4. Why has the scaling law failed ?

Scaling relation

Scaling relation

Fits to RS = a ρ + b ρn with a = 0 yield n much larger than 2 as found earlier in

Fe-Cr, Co-Cu, and Co-Ag films. [Y. Aoki et al., J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 126 , 448

(1993); T. Lucin´ski et al., J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 160 , 347 (1996); V. Korenivski et

al., Phys. Rev. B 53 , R 11 938 (1996).]

The exponent is larger for samples having higher GMR !!!

77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-77-320.jpg)

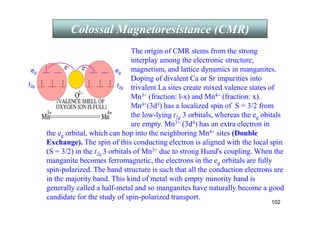

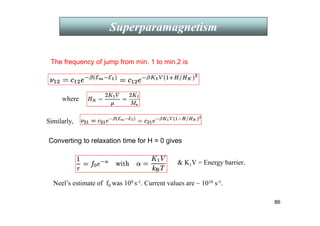

![81

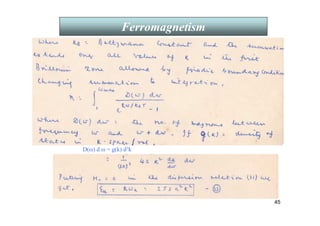

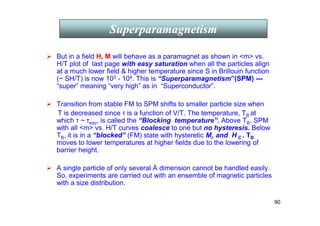

Nano-scale magnetism: Magnetic properties like Tc(Curie

temperature), Ms(Saturation magnetization), and Hc (Coercive

field) change as the size reduces to 100 nm, due to higher

surface /volume ratio.

(A) (B) (C)

(A) Specific magnetization vs. temperature at 1.2 tesla.

(B) Specific magnetization vs. average diameter of Ni particles.

(C) Coercivity vs. average diameter of Ni particles.

[You-wei Du, Ming-xiang Xu, Jian Wu, Ying-bing Shi, and Huai-xian Lu,

J. Appl. Phys. 70, 5903 (1991).]

Electrical transport properties are seriously affected by grain

boundary scattering.

Nano-magnetism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-81-320.jpg)

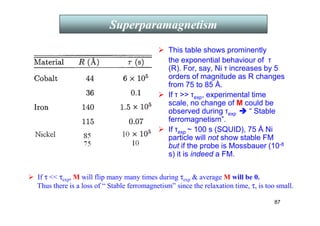

![88

The final form of m along the direction of H comes out to be

where BS (x) is the Brillouin function

Paramagnetism

=

T

k

SH

g

SB

g

m

B

B

S

B

µ

µ

−

+

+

=

S

x

S

S

x

S

S

S

2

coth

2

1

2

)

1

2

(

coth

2

1

2

where S is the spin of the ion.

m = g µ

µ

µ

µB [coth x- 1/x] = L(x) = Langevin function when S →

→

→

→ ∞

∞

∞

∞ .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-88-320.jpg)

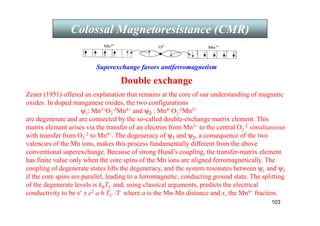

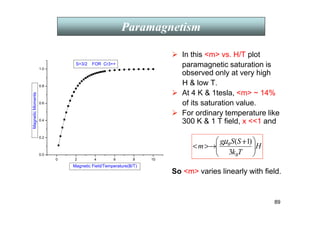

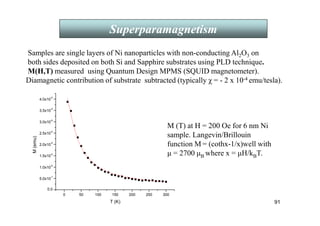

![93

A cross-sectional STEM-Z image

Ni [220] || TiN[002]

Ni[110] || TiN[110]

Ni [002] || TiN[002]

Ni[110] || TiN[110]

Single layer epitaxial Ni nano dots on TiN/Si(100) template

Ni separation ≈ 10 nm

Triangular morphology

with 17 nm base and

9 nm height

Some have rectangular

morphology.

Thickness of TiN = 6×32 nm.

Ni particles grow epitaxially on TiN acting as a template which also

grows epitaxially on Si.

Ni-nano/TiN is an ideal system for studying electrical transport in magnetic

nano particles due to epitaxial growth and conducting nature of TiN .

Nano-magnetism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-93-320.jpg)

![94

Hall Effect

0 1 2 3 4 5

0

1x10

-10

2x10

-10

3x10

-10

4x10

-10

5x10

-10

6x10

-10

T=25K

T = 300K

Hall effect

Ni-Nano/TiN

Hall effect

Pure Ni-bulk

11K

35K

60K

85K

105K

115K

135K

160K

185K

210K

235K

260K

290K

T=290K

T=11K

Hall

Resistivity

(-

ρ

H

)(ohm-m)

Field (tesla)

Hall resistivity (ρH) vs. applied magnetic field (µ0Happlied ).

ρH is negative at all temperatures from 11 to 290 K.

In Hall geometry B = µ0[Happlied+ (1-N) M], N=demagnetization factor.

So, ρH = Ro µ0 Happlied + RS µ0 M,

Nano-magnetism](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-94-320.jpg)

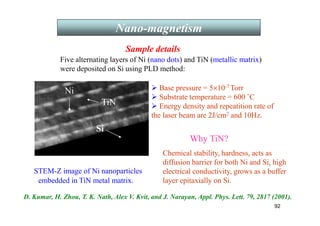

![95

-3000 -2000 -1000 0 1000 2000 3000

-1.8

-1.2

-0.6

0.0

0.6

1.2

1.8

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0 100 200 300

50

100

150

200

250

Hc

H

C

(Oe)

T (K)

M

r

(10

-4

emu)

Mr

M

(10

-

4

emu)

Field (tesla)

(10 K)

(100 K)

(300 K)

Magnetization vs. applied field at 10, 100 and 300 K.

Inset: Coercivity remanent magnetization vs. T.

Magnetization

Nano-magnetism

[P. Khatua, T. K. Nath, and A. K. Majumdar, Phys. Rev. B 73, 064408 (2006).]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/10344076-240909171948-1e3df6f2/85/NANO-MAGNETIC-MATERIALS-AND-APPLICATIONS-95-320.jpg)