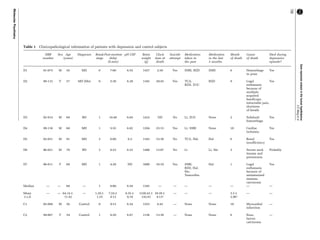

The document summarizes a study that analyzed gene expression in the hypothalamus of depressed patients compared to controls using laser microdissection and real-time PCR. The study found increased expression of genes involved in activating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in depressed patients, including corticotropin-releasing factor and receptors for estrogen, vasopressin, and mineralocorticoids. Expression of the androgen receptor, which inhibits the axis, was decreased. This suggests an imbalance in receptor production may contribute to axis hyperactivity in depression. The findings provide molecular evidence for the corticotropin-releasing factor hypothesis of depression.