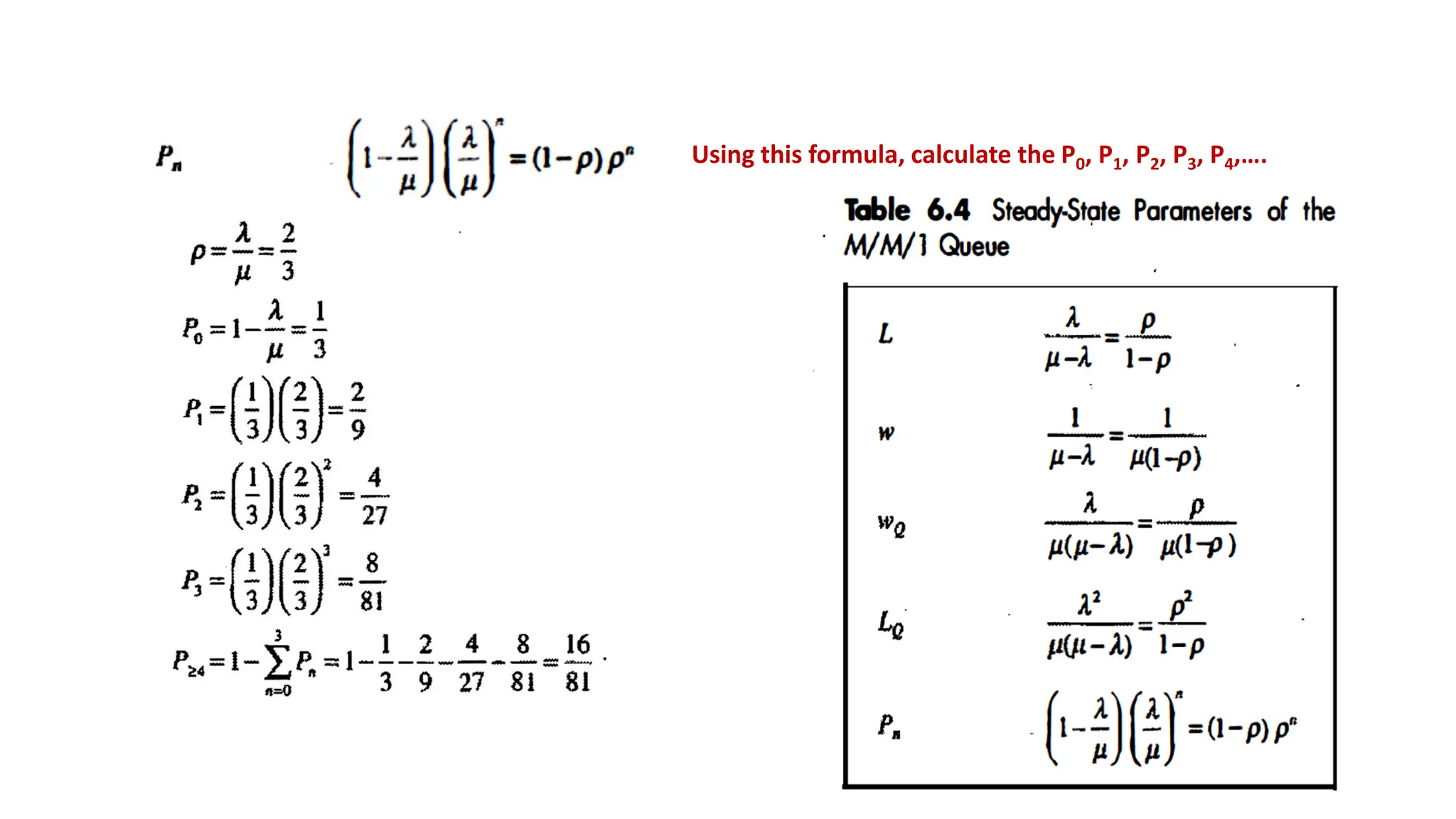

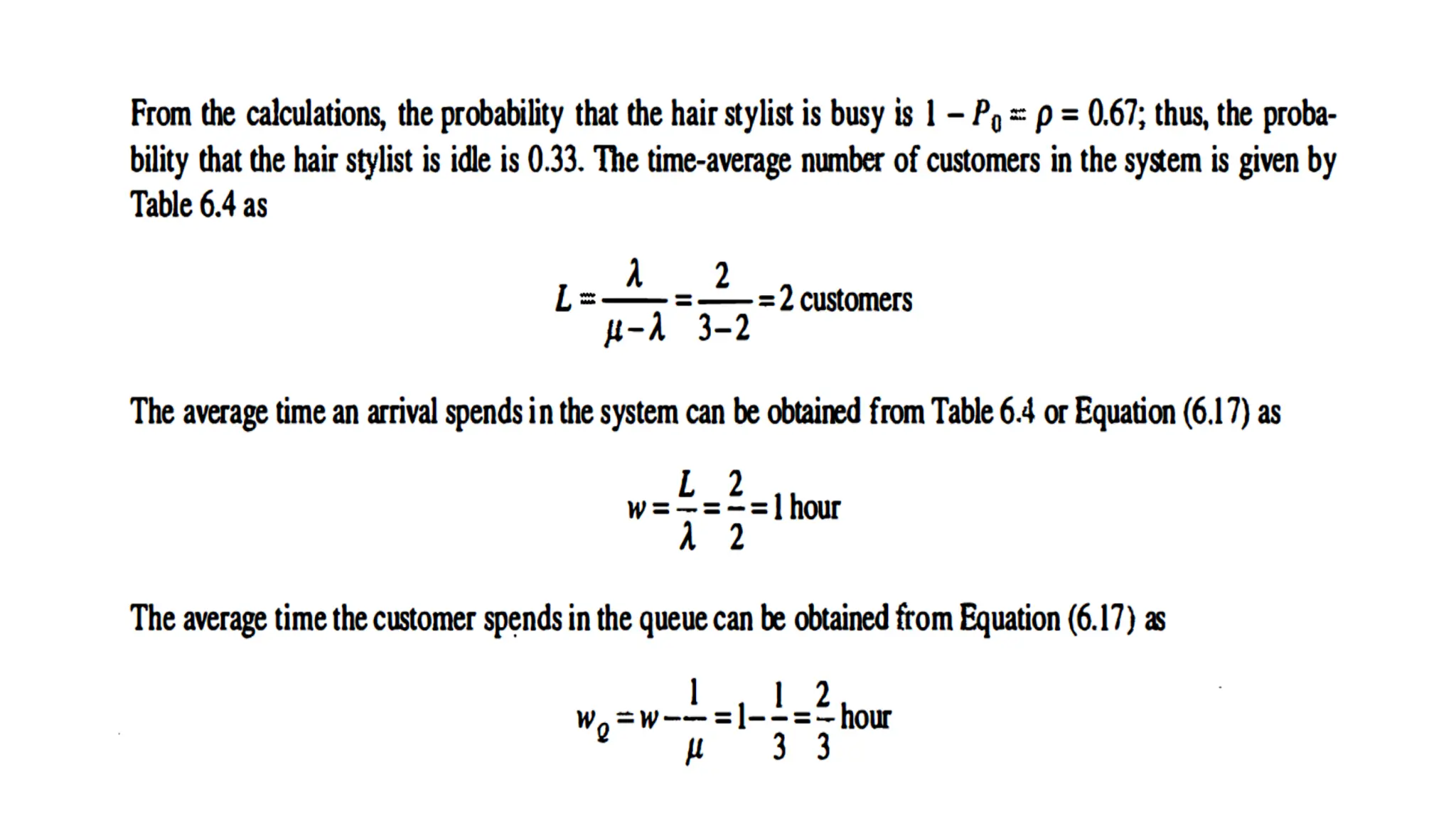

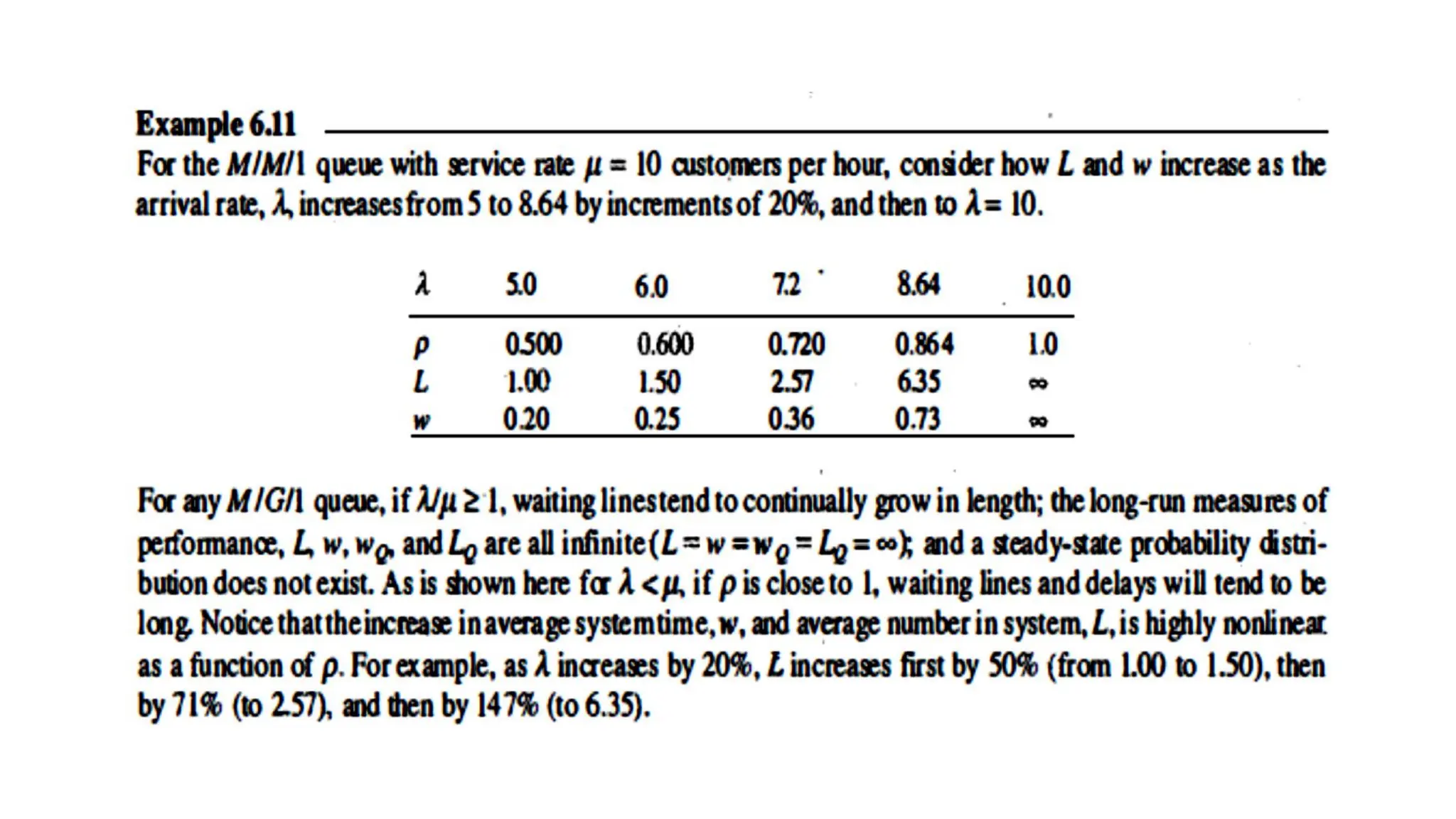

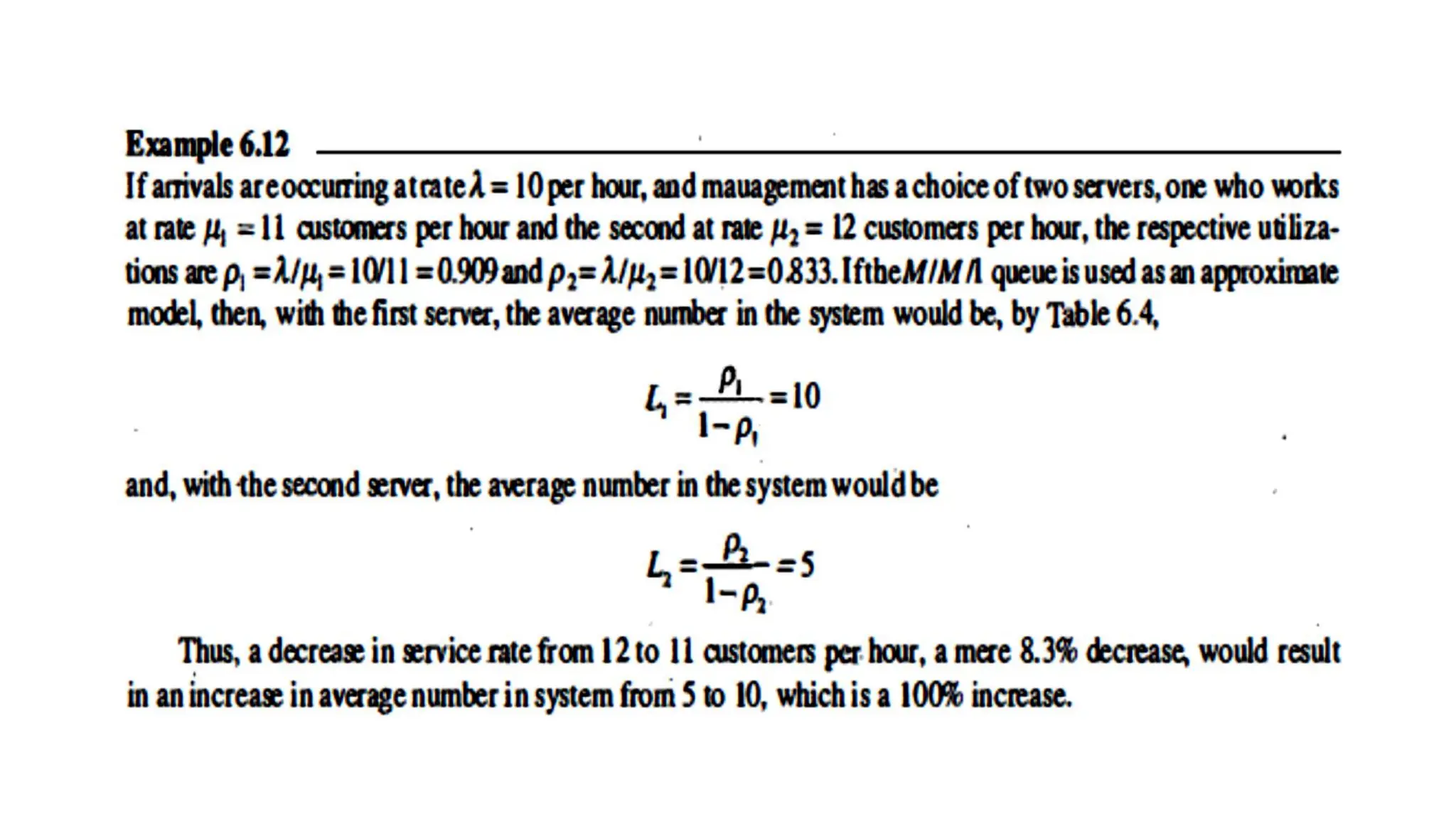

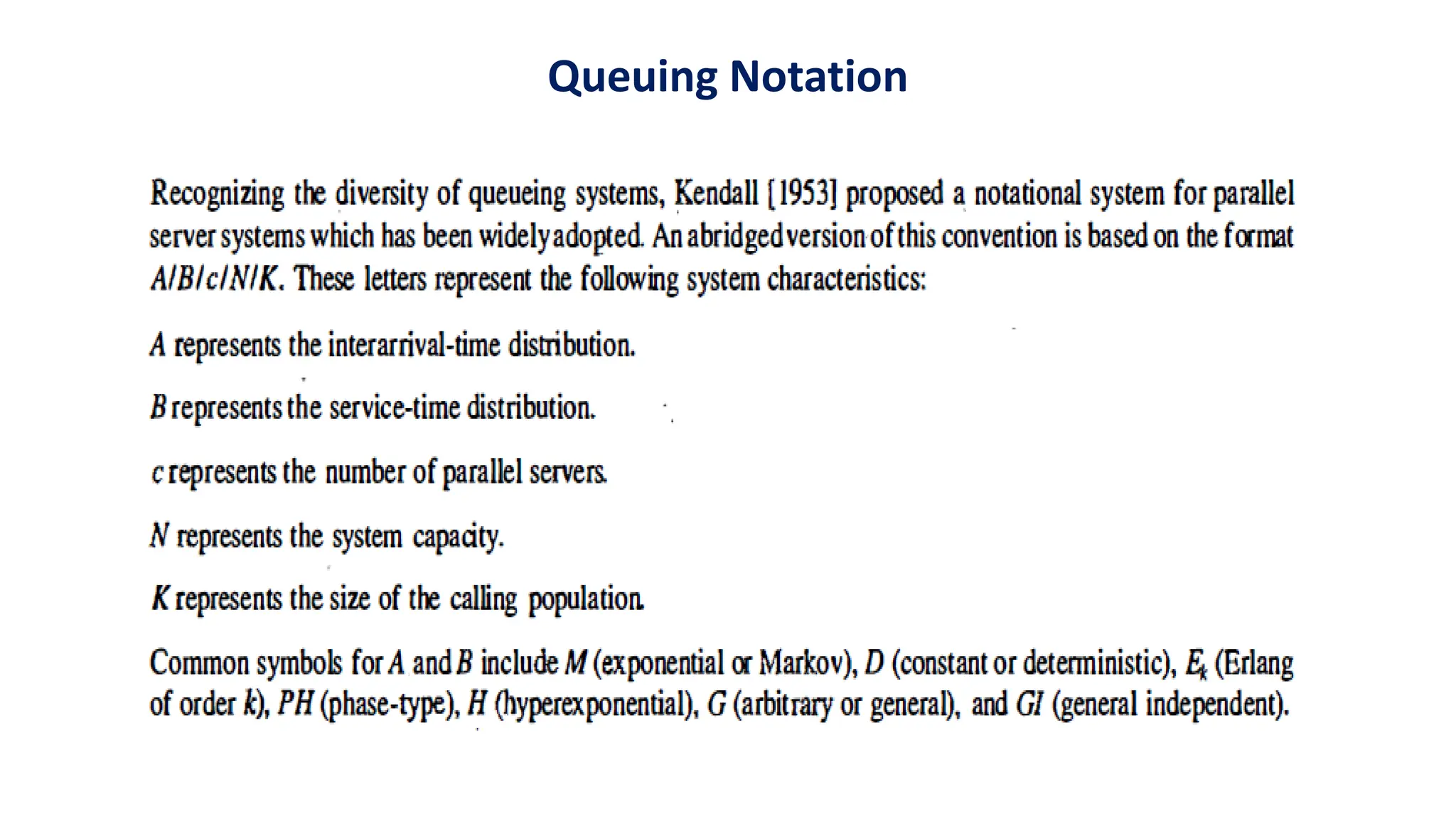

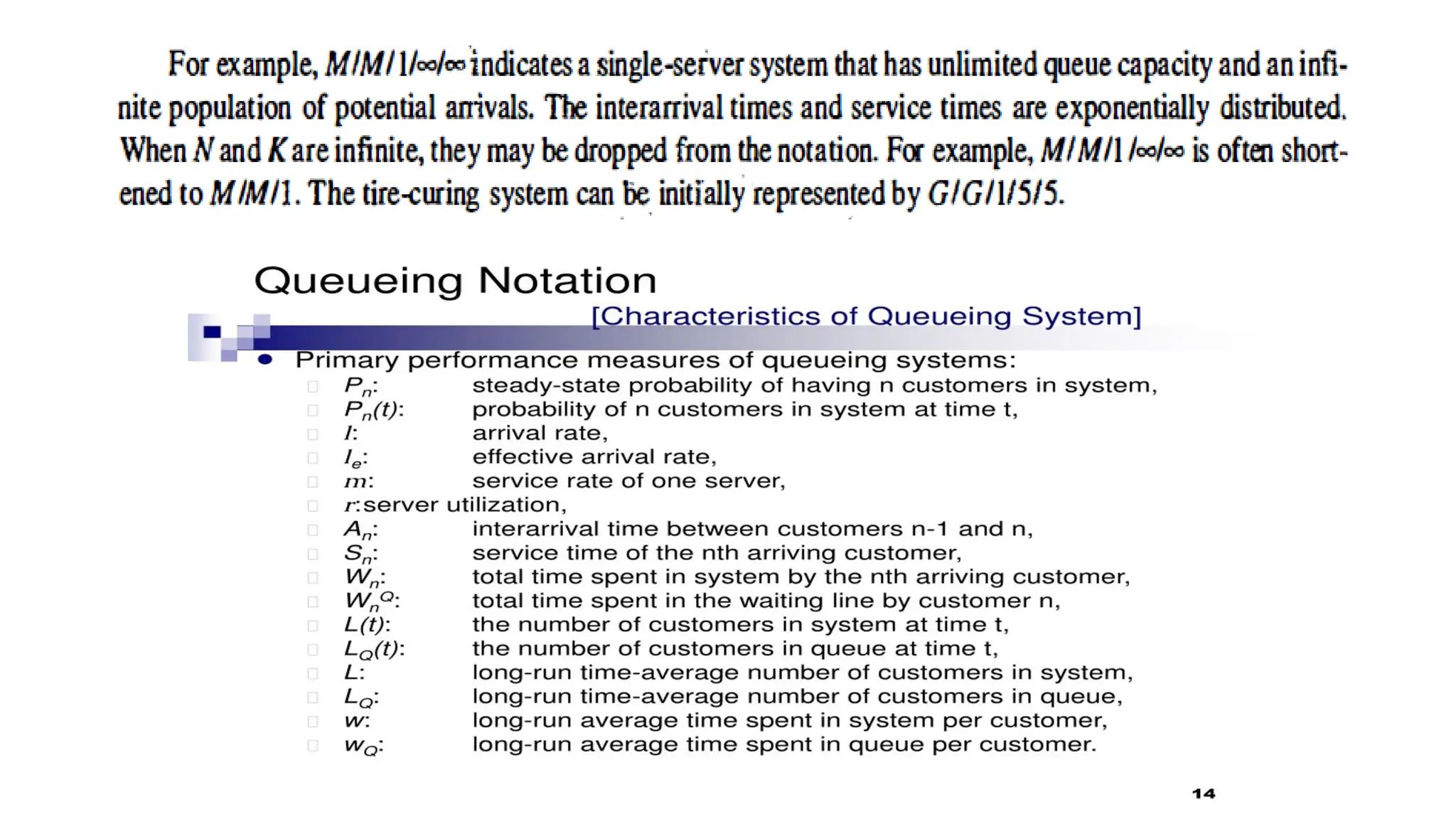

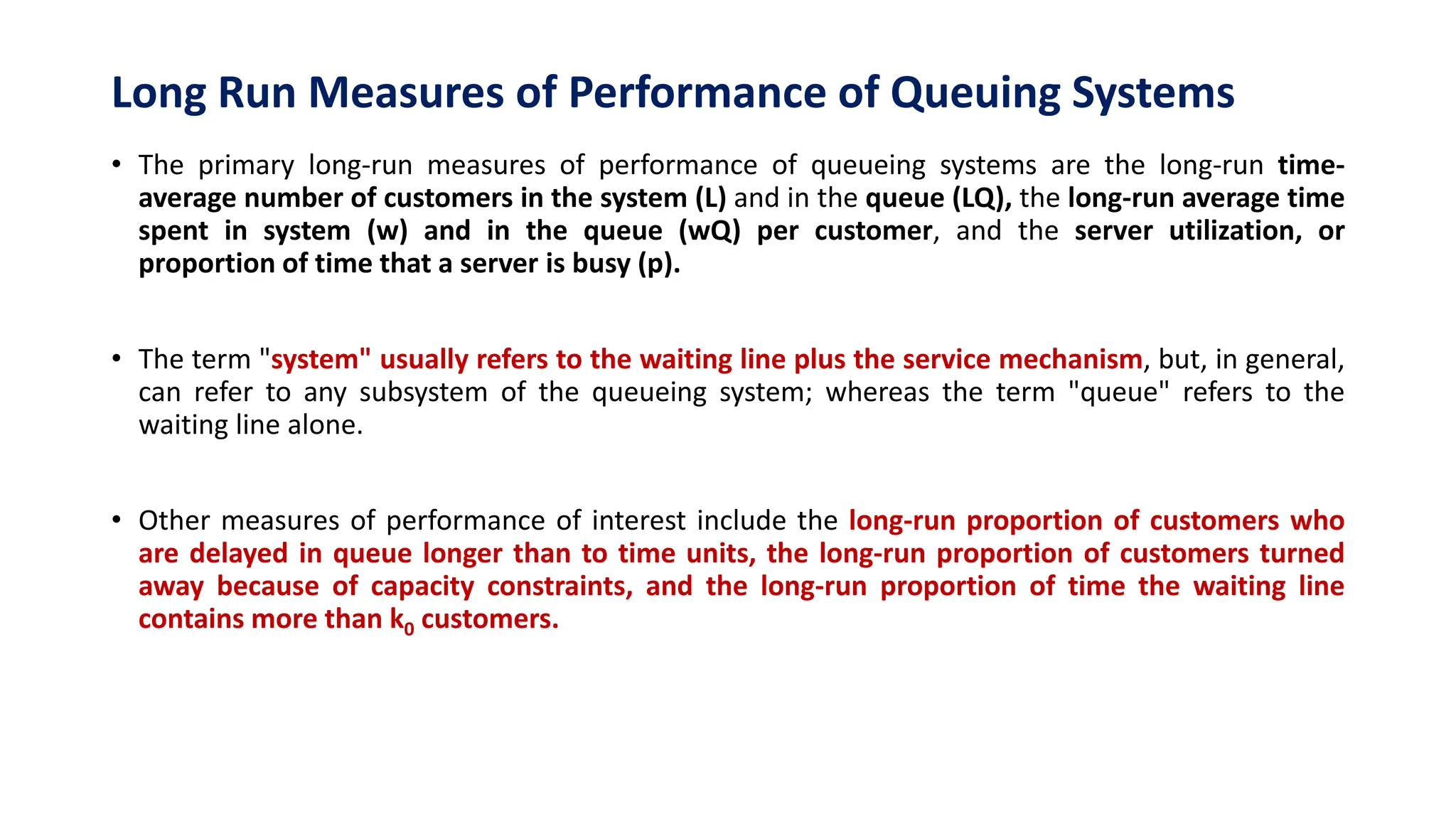

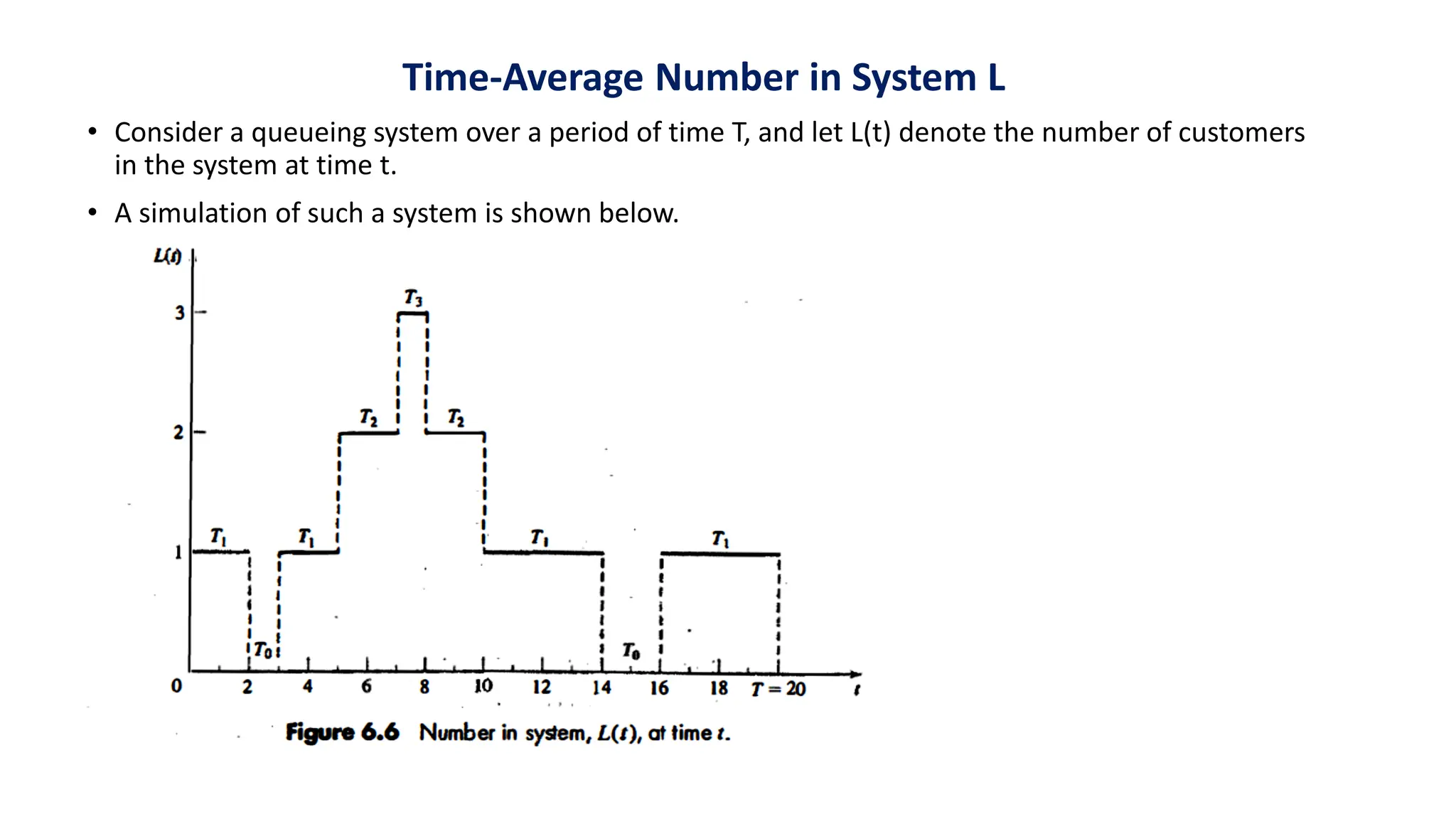

The document discusses queuing models, detailing characteristics of service times, types of service mechanisms, and performance measures of queuing systems. It outlines key metrics such as the average number of customers in the system, time spent in the system, and server utilization, along with various queuing notations. Additionally, it addresses the behavior of single and multiple server systems under various conditions and the implications of capacity constraints in networked queuing environments.

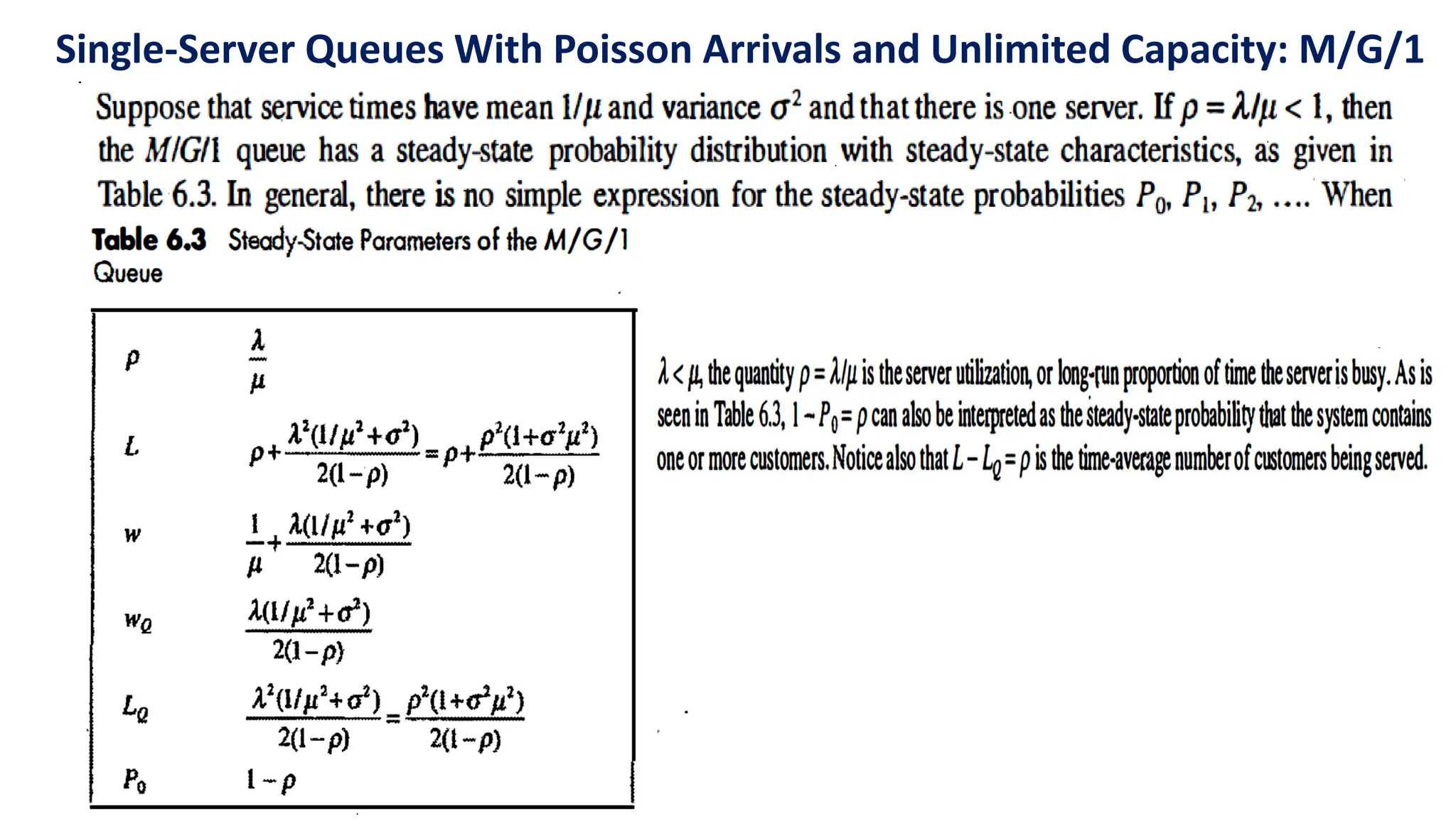

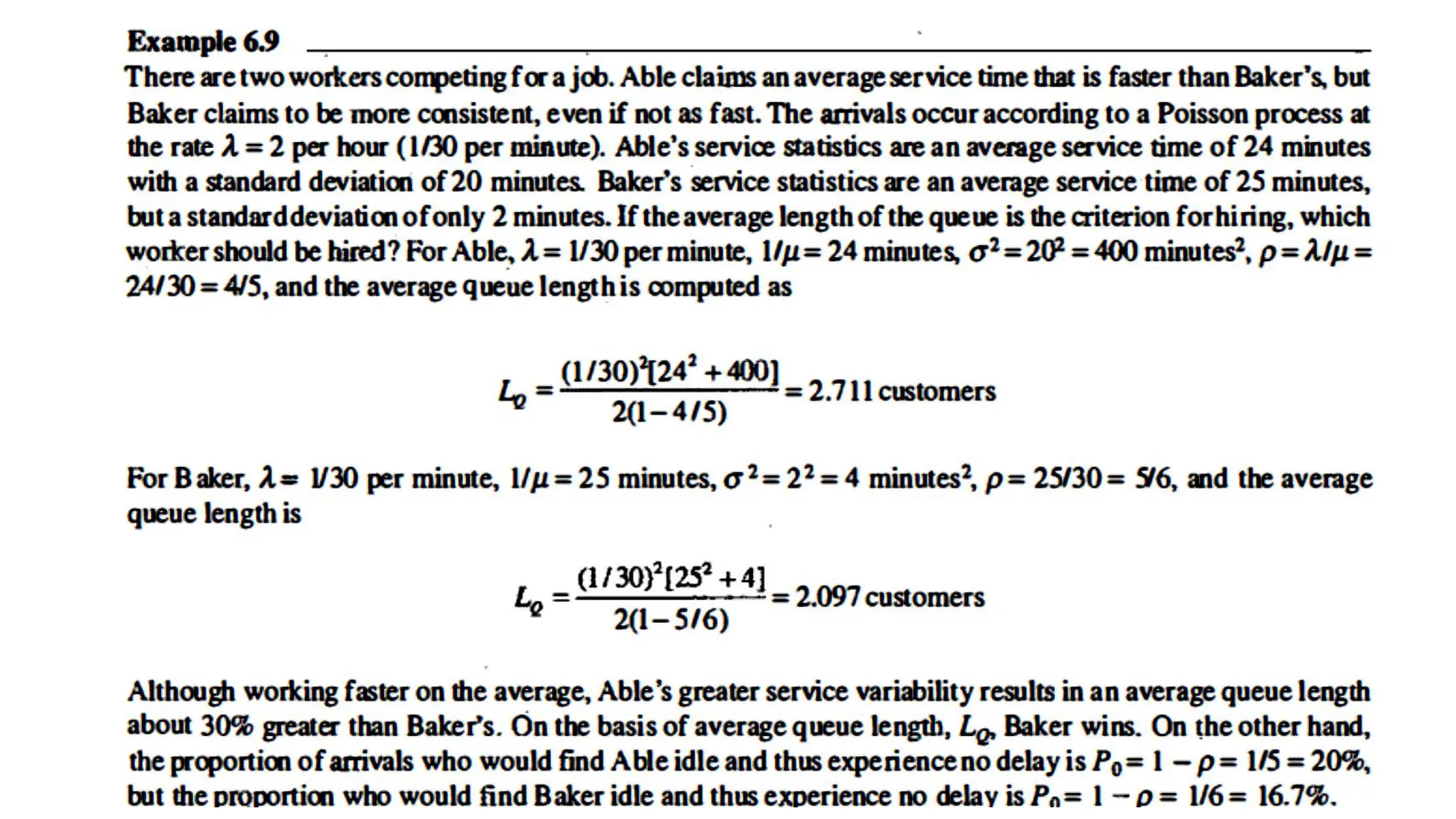

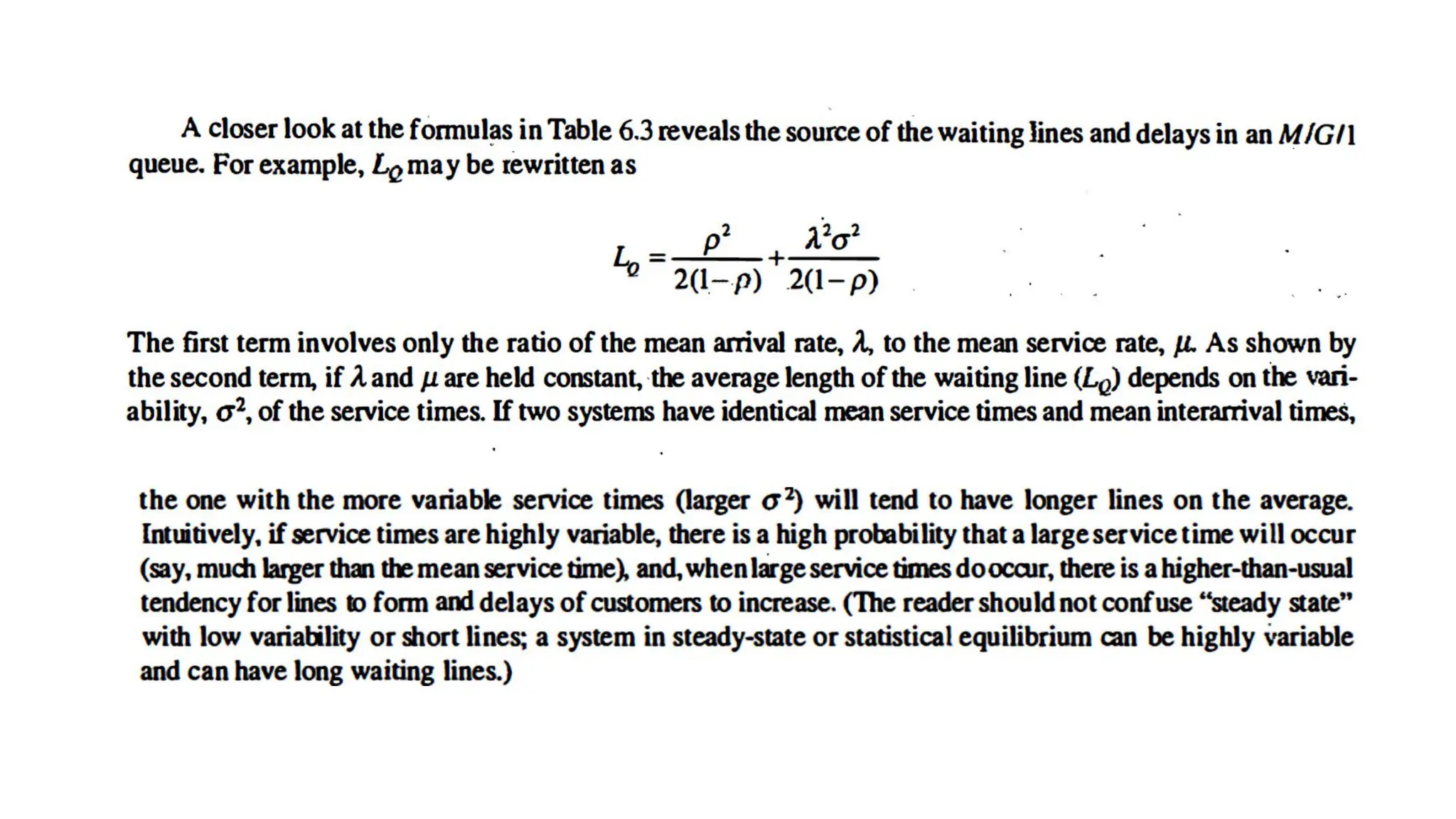

![Average Time Spent in System Per Customer w

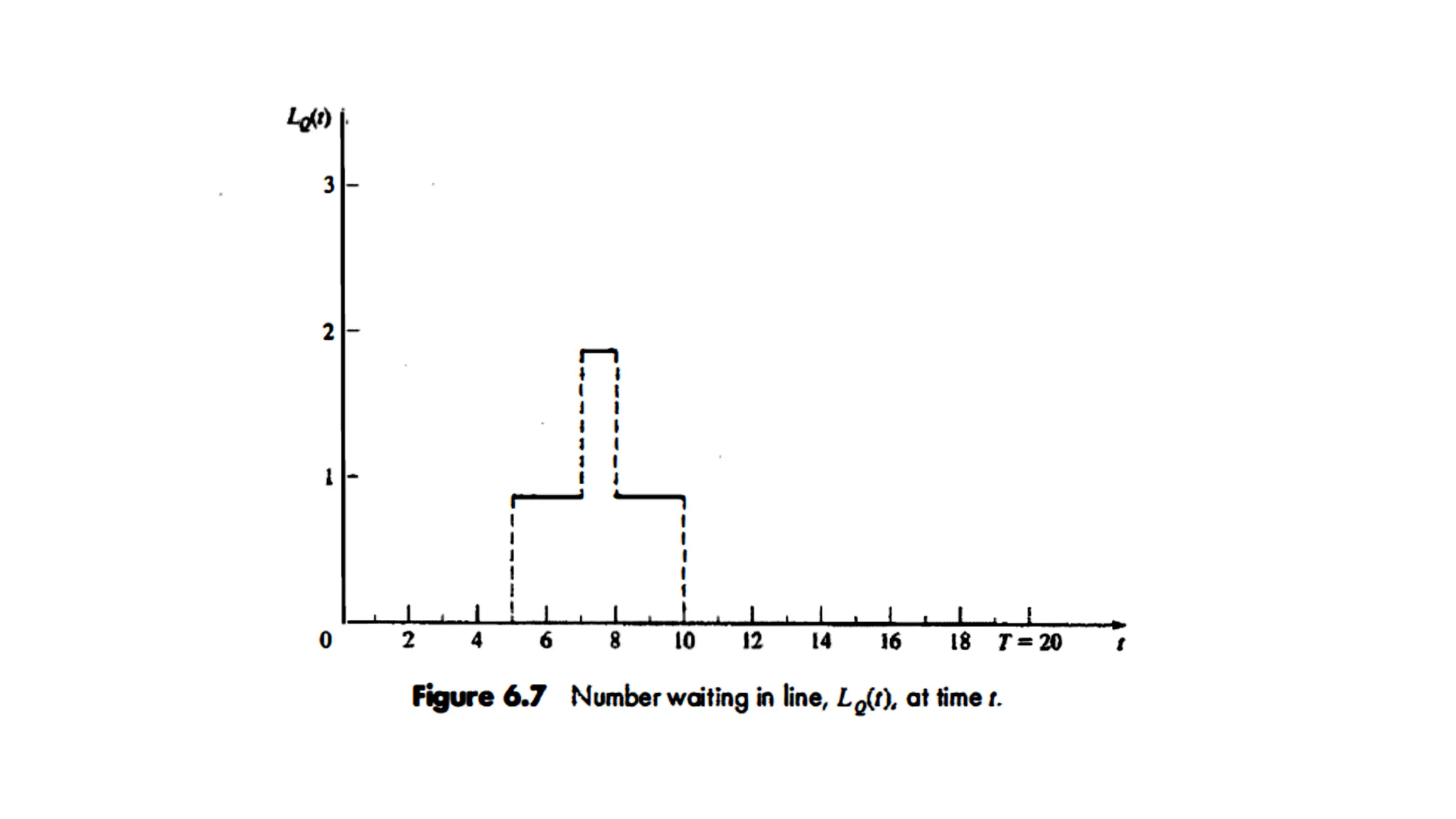

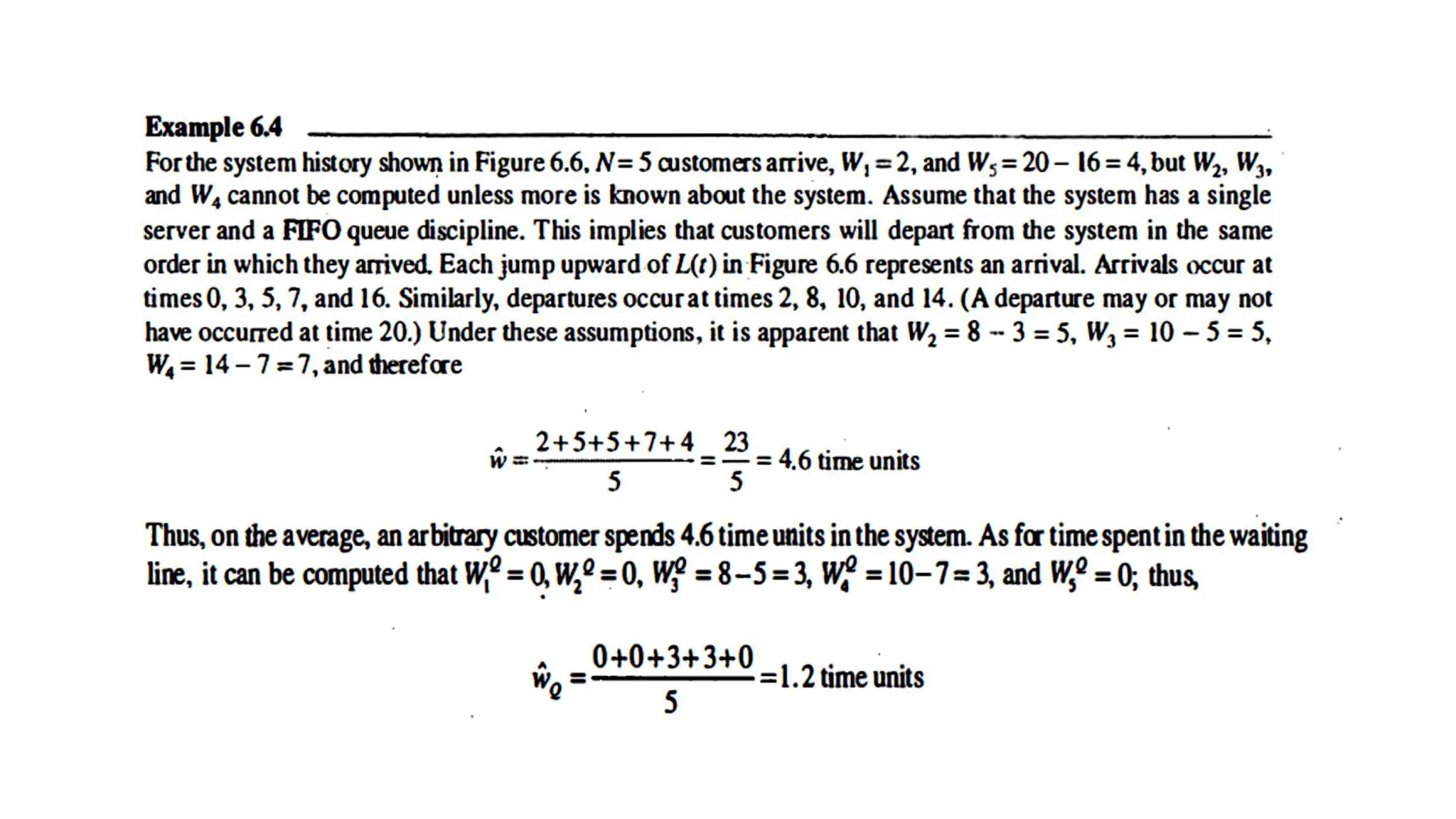

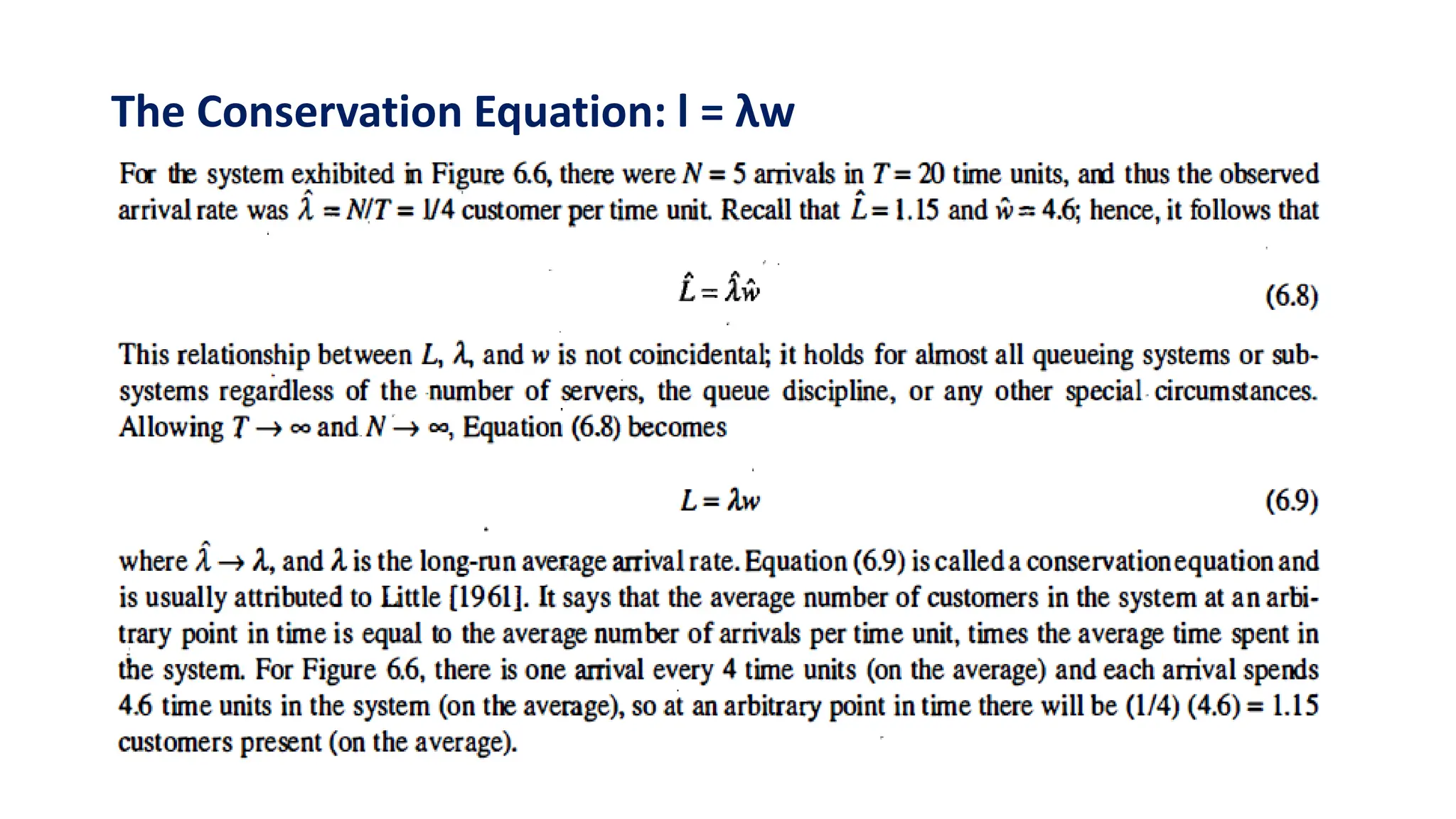

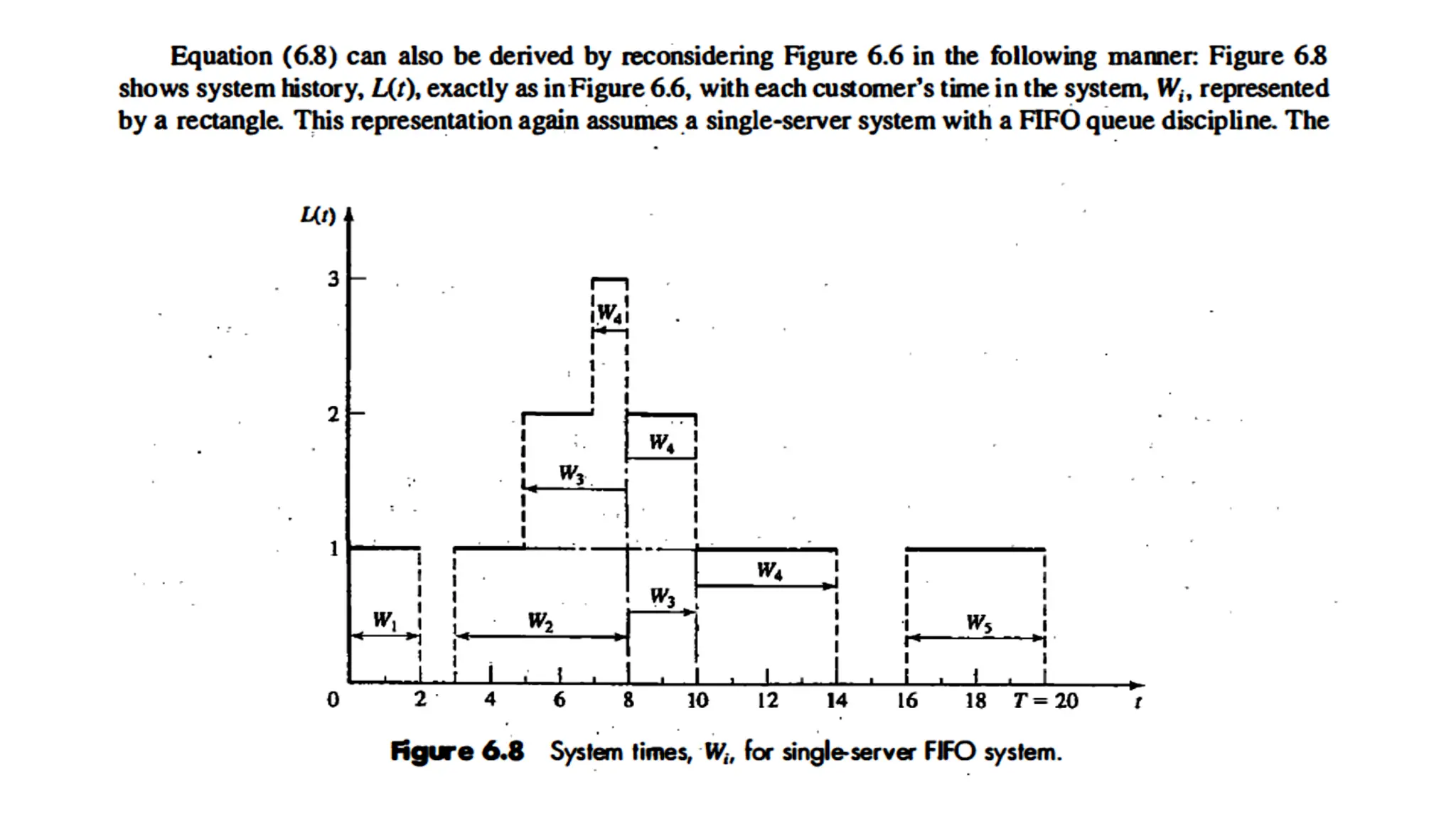

• If we simulate a queueing system for some period of time, say T, then we can record the time

each customer spends in the system during [0, T], say W1, W2, . . ., WN> where N is the number

of arrivals during [0, T].

• The average time spent in system per customer, called the average system time, is given by the

ordinary sample average,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/module2-queuingmodels-240419112712-f0a201c3/75/Module-2-Queuing-Models-and-notations-pdf-20-2048.jpg)