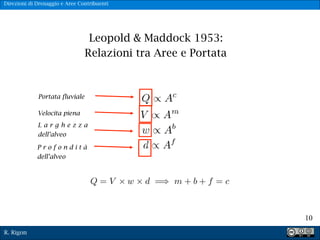

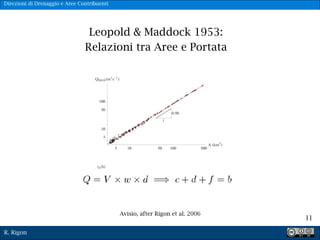

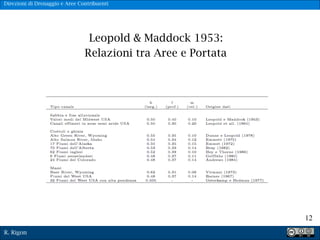

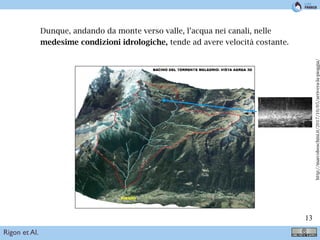

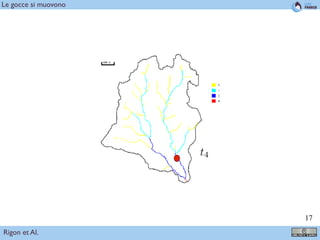

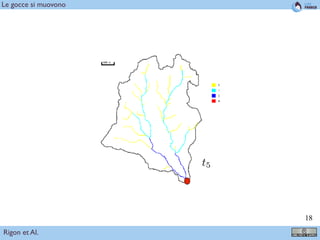

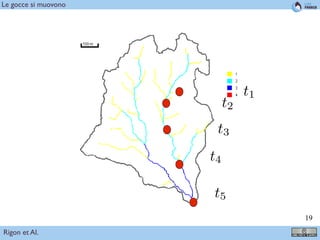

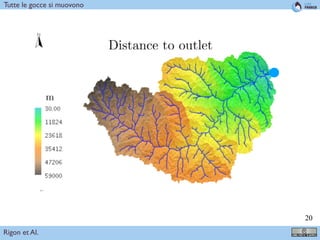

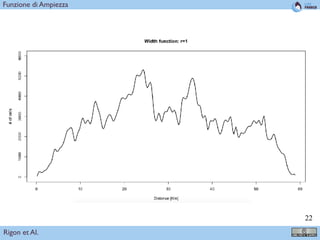

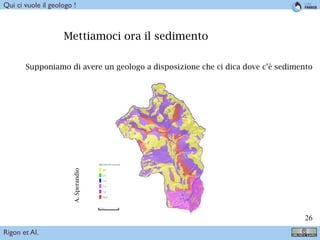

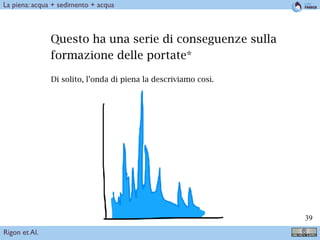

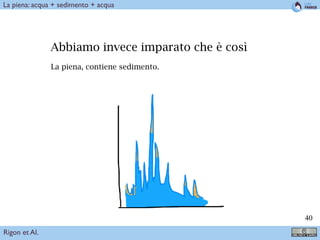

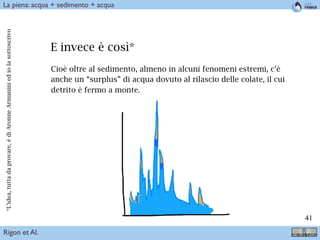

Il documento presenta un'analisi geologica del torrente Meledrio in Val di Sole, evidenziando la sua morfologia e le caratteristiche idrologiche. Viene descritto l'impatto della gravità e delle pendenze sul movimento dell'acqua, e si discutono i principi dell'espressione energetica nei sistemi di drenaggio. Inoltre, si menzionano le applicazioni pratiche e teoriche per comprendere la gestione delle risorse idriche e la stabilità del suolo.

![!7

WATER RESOURCESRESEARCH,VOL. 28,NO. 4, PAGES 1095-1103,APRIL 1992

EnergyDissipation,RunoffProduction,and the Three-Dimensional

Structure of River Basins

IGNACIORODRfGUEZ-ITURBE,I,2ANDREARINALDO,3RICCARDORIGON,'*

RAFAELL. BRAS,2ALESSANDROMARANI,4 AND EDE IJJ/(Sz-VXSQUEZ2

Threeprinciplesof optimalenergyexpenditureare usedto derivethe mostimportantstructural

characteristicsobservedindrainagenetworks:(I) theprincipleofminimumenergyexpenditureinany

linkofthenetwork,(2)theprincipleofequalenergyexpenditureperunitareaof channelanywherein

the network,and(3) the principleof minimumtotal energyexpenditurein the networkas a whole.

Theirjoint applica,tionresultsin a unifiedpictureof themostimportantempiricalfactswhichhave

beenobservedin thedynamicsof thenetworkanditsthree-dimensionalstructure.They alsolink the

processof runoffproductionin thebasinwiththecharacteris.ticsof the network.

INTRODUCTION' THE CONNECTIVITY ISSUE

Well-developedriver basinsare made up of two interre-

latedsystems'the channelnetwork and the hillslopes.The

hillslopescontrolthe productionof runoffwhichin turn is

transportedthroughthe channelnetworktowardthe basin

outlet.Every branch of the network is linked to a down-

streambranchfor the transportation of water and sediment

butit is also linked for its viability, throughthe hillslope

system,toevery otherbranchin the basin.Hillslopesarethe

runoff-producingelements which. the n.etwork connects,

transformingthe spatially distributedpotential ,energyaris-

ingfromrainfallin the hillslopesto kineticenergyin theflow

throughthe channelreaches. In this paper we focuson the

drainagenetwork as it is controlled by energy dissipation

principles.It !spreciselytheneedfor effectiveconnectivity

thatleadsto the treelike structureof the drainagenetwork.

Figure!, from Stevens[1974], illustratesthis point. Assume

onewishestoconnectasetofpointsinaplanetoacommon

outletandfor illustrationpu.rposesassumethat everypoint

isequallydistantfrom its nearestneighbors.Two extreme

waystoestablishthe connectionwouldbe throughthe spiral

andtheexplosiontype of patterns.The explosionpattern

hastheadvantagethatit connectseveryparcelofthesystem

to the outlet in the most direct manner. Nevertheless it

.rejectsanykindof interactionbetweenthedifferentparts

andthe total path lengthfor the systemas a whole is

case each individualis supposedto operate at his best

completelyobliviousof his neighbors,but the systemas a

whole cannot survive.

Branchingpatterns accomplish connectivity combining

thebestof thetwo extremes;they are shortaswell asdirect.

The drainagenetwork, as well as many other natural con-

nectingpat.terns, is basically a transportationsygtemfor

which the treelike structure is a most appealing structure

from the point of view of efficiency in the construction,

operation and maintenance of the system.

The drainage network accomplishes connectivity for

transportationin three dimensions working against a resis-

tance force derived from the friction of the flow with the

bottomandbanksof the channels, the resistanceforce being

itself a function of the flow and the channel characteristics.

This makesthe analysisof the optimal connectivity a com-

plex problem that cannot be separated from the individual

optimalchannelconfigurationandfrom .thespatialcharac-

terization of the runoff production inside the basin. The

questionis whethertherearegeneralprinciplesthatrelate

thestructureof the network and its individualelementsWith

the rate of energy expenditure which takes place in the

systemas a whole and in each of its elements.

PRINCIPLESOF ENERGY EXPENDITURE

IN DRAINAG.ENETWORKS

1096 RODFffGUEZ-ITURBEET AL,' STRUCTUREOF DRAINAGE NETWORKS

233.1,•--303,3

L- 3.73

Fig. 1. Different patterns of connectivity of a set of equally

spacedpointstoa commonoutlet.L r isthetotallengthof thepaths,

andL is the averagelengthof the pathfrom a pointto the outlet. In

theexplosioncase,L•2)referstothecasewhenthereisaminimum

displacementamong the points so that there is a different path

betweeneachpoint and the outlet [from Stevens,1974].

network; (2) the principle of equal energy expenditureper

unit area of channel anywhere in the network; and (3) the

principleof minimumenergyexpenditurein the networkas

a whole. It will be shown that the combination of these

principlesis a sufficientexplanationfor the treelike structure

of the drainagenetwork and, moreover, that they explain

manyof themostimportantempiricalrelationshipsobserved

in the internal organizationof the network and its linkage

with the flow characteristics.The firstprincipleexpressesa

local optimal condition for any link of the network. The

secondprinciple expressesan optimal conditionthroughout

the network regardlessof its topologicalstructureand later

on in this paperwill be interpretedin a probabilisticframe-

work. It postulates that energy expenditure is the same

equalthesumofthecubesoftheradiiofthedaughter

vessels(see,forexample,Sherman[1981]).Heassumedthat

twoenergytermscontributetothecostofmaintainingblood

flowin anyvessel:(1) theenergyrequiredto overcome

frictionasdescribedbyPoiseuille'slaw,and(2)theenergy

metabolicallyinvolvedin the maintenanceof theblood

volumeandvesseltissue.Minimizationofthecostfuncfi0a

leadstotheradiusofthevesselbeingproportionaltothelB

powerof the flow. Uylings[1977]hasshownthatwhen

turbulentflowisassumedinthevessel,ratherthanlain'mar

conditions,thesameapproachleadstotheradiusbe'rag

proportionalto the 3/7 power of the flow. The secorot

principlewasconceptuallysuggestedbyLeopoldandLang.

bein[1962]in theirstudiesof landscapeevolution.It isof

interestto addthatminimumrate of workprincipleshave

been appliedin severalcontextsin geomorphicresearch.

Optimaljunctionangleshavebeenstudiedinthiscontextby

Howard[1971],Roy [1983],andWoldenbergandHorsfield

[1986],amongothers.Also the conceptof minimumworkas

a criterion for the developmentof streamnetworkshasbeen

discussedunder differentperspectivesby Yang[1971]a•d

Howard [1990], amongothers.

ENERGY EXPENDITURE AND OPTIMAL NETWORK

CONFIGURATION

Considera channelof width w, lengthL, slope$, andflow

depthd. The forceresponsiblefor theflowisthedownslope

componentof the weight, F1 = ptldLw sin /3 = ptIdLwS

where sin/3 = tan/3 = S. The force resistingthemovement

is the stressper unit area times the wetted perimeterarea,

F2 = •(2d + w)L, where a rectangularsectionhasbeen

assumed in the channel. Under conditions of no acceleration

of the flow, F1 = F 2, and then r = p.qSRwhereR isthe

hydraulicradiusR = Aw/Pw = wd/(2d + w), Awand

beingthe cross-sectionalflow area, andthewettedperimeter

ofthesection,respectively.In turbulentincompressibleflow

theboundaryshearstressvariesproportionallytothesqua•

oftheaveragevelocity,r = Cfpv2,whereCfisadimen.

sionlessresistancecoefficient.Equatingthetwoexpressions

for,, oneobtainsthewell-knownrelationship,S= Cfv2/

(R•/),whichgivesthelossesduetofrictionperunitweightof

flowperunitlengthofchannel.Thereisalsoanexpendi•

of energyrelatedto themaintenanceof thechannelw•ch

mayberepresentedby F(soil,flow)P•L whereF( ) isa

complicatedfunctionofsoilandflowpropertiesrepresenf•

theworkperunittimeandunitareaofchannelinvolved'm

theremovalandtransportationof thesedimentwhich0th-

erwise would accumulatein the channel surface.Fromthe

equationsofbedloadtransportonemayassumethatF =

Perchè i fiumi hanno

questa forma, piuttosto

che le altre ?

Rigon et Al.

Bella domanda !](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/modelli-171022083807/85/Models-for-hazards-mapping-7-320.jpg)