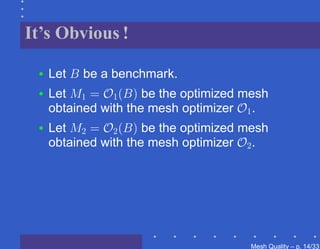

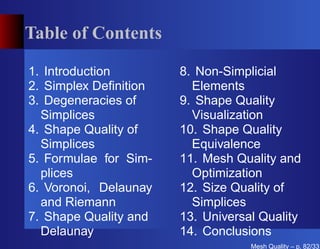

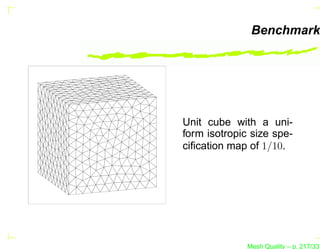

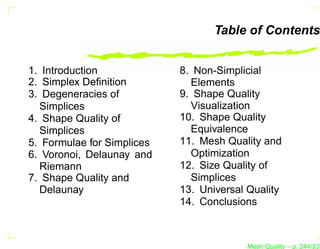

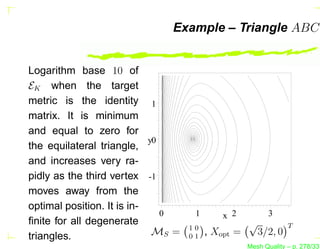

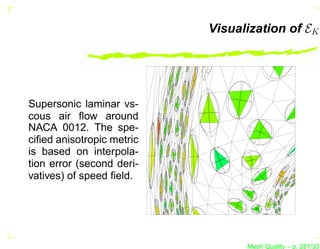

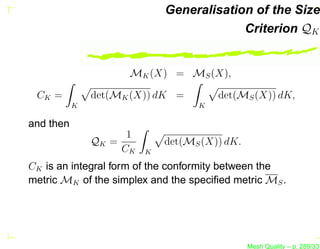

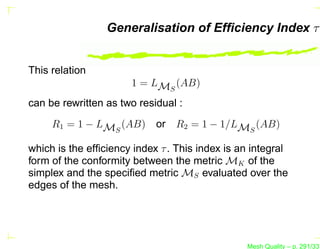

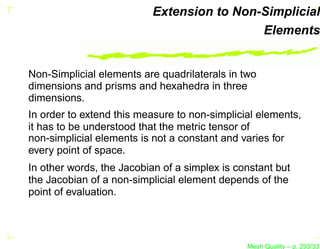

The document discusses mesh quality, emphasizing the importance of measuring the shape quality of simplices in two and three dimensions for mesh generation, adaptation, and optimization. It covers various terms, definitions, and concepts related to simplices, including degeneracies and criteria for identifying degenerate simplices. Additionally, the authors propose benchmarks for optimizing three-dimensional tetrahedral meshes.

![Simplicial Shape Measure

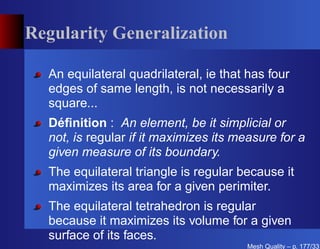

Definition A : A simplicial shape measure is a

continuous function that evaluates the shape of a simplex.

It must be invariant under translation, rotation, reflection

and uniform scaling of the simplex. A shape measure is

called valid if it is maximal only for the regular simplex and

if it is minimal for all degenerate simplices. Simplicial

shape measures are scaled to the interval [0, 1], and are 1

for the regular simplex and 0 for a degenerate simplex.

Mesh Quality – p. 46/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-84-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![The Mean Ratio

Let R(r1 , r2 , r3 [, r4 ]) be an equilateral simplex having the

same [area|volume] than the simplex K(P1 , P2 , P3 [, P4 ]). Let

N be the matrix of transformation from R to K, i.e.

Pi = N ri + b, 1 ≤ i ≤ [3|4], where b is a translation vector.

s y K

K = NR + b

R

r

b

x

Mesh Quality – p. 49/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-89-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![The Mean Ratio

Then, the mean ratio η of the simplex K is the ratio of the

geometric mean over the algebraic means of the

eigenvalues λ1 , λ2 [,λ3 ] of the matrix N T N .

√ √

2 λ1 λ2

2

4 3 SK

d

λ +λ = in 2D,

d

λi 1 2

2

1≤i<j≤3 Lij

i=1

η= =

d

1

λi 3 √λ 1 λ 2 λ 3

3

12 3 9VK2

d

i=1 λ +λ +λ = L 2

in 3D.

1 2 3 1≤i<j≤4 ij

Mesh Quality – p. 50/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-90-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![There Exists an Infinity of Shape

Measures

If µ and ν are two valid shape measures, if c, d ∈ R+ , then

µc ,

c(µ−1)/µ with c > 1,

αµc + (1 − α)ν d with α ∈ [0, 1],

µc ν d

are also valid simplicial shape measures.

Mesh Quality – p. 64/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-104-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![Length in a Variable Metric

In the general sense, the metric tensor M is not

constant but varies continuously for every point

of space. The length of a parameterized curve

γ(t) = {(x(t), y(t), z(t)) , t ∈ [0, 1]} is evaluated in

the metric

1

LM (γ) = (γ ′ (t))T M (γ(t)) γ ′ (t) dt,

0

where γ(t) is a point of the curve and γ ′ (t) is the

tangent vector of the curve at that point. LM (γ) is

always bigger or equal to the geodesic between

the end points of the curve.

Mesh Quality – p. 144/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-203-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

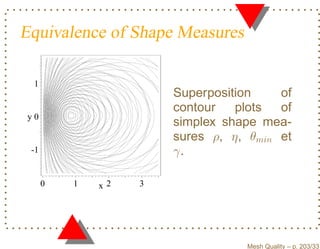

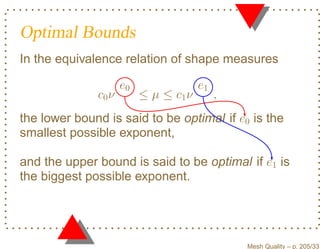

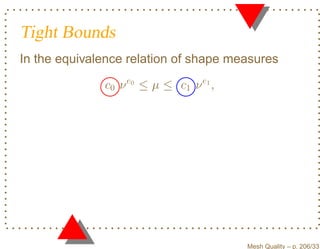

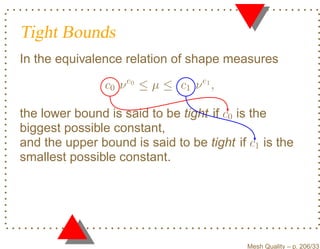

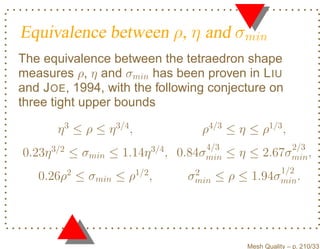

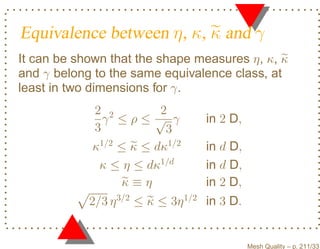

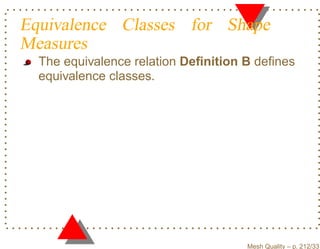

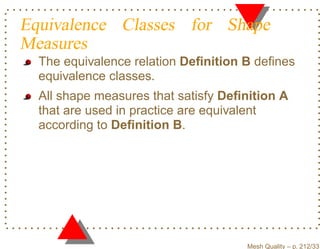

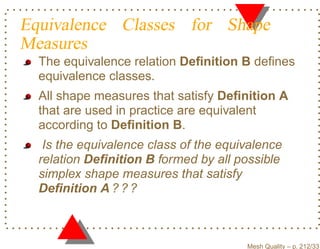

![Equivalence of Shape Measures

Definition B (from L IU and J OE, 1994) : Let µ

and ν be two different simplicial shape measures

having values in the interval [0, 1]. µ is said to be

equivalent to ν if there exists positive

constants c0 , c1 , e0 and e1 such that

c0 ν e0 ≤ µ ≤ c1 ν e1 .

Mesh Quality – p. 204/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-277-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

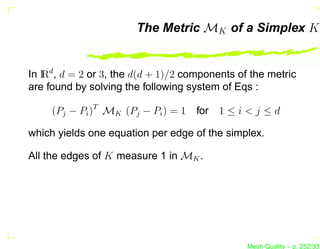

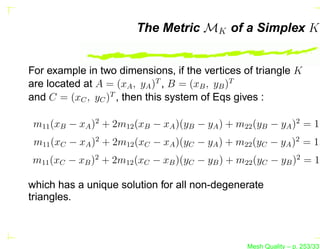

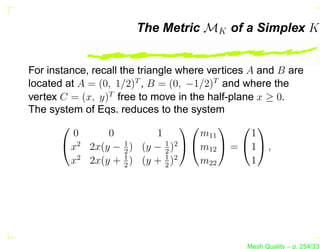

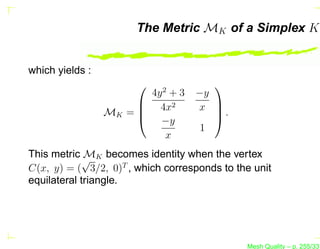

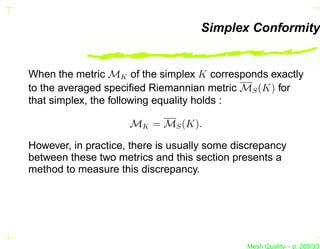

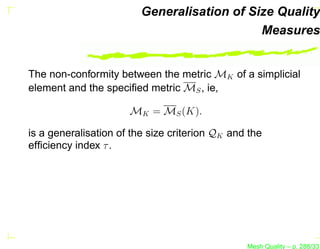

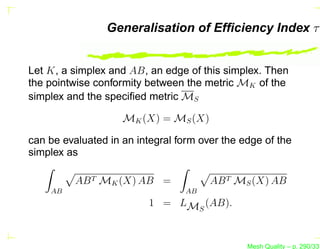

![The Metric MK of a Simplex K

How to compute the metric MK of the transformation that

transforms a simplex K into a unit equilateral element ?

Let P1 , P2 , P3 [, P4 ], the d + 1 vertices of the simplex K

in I d .

R

Let Pi Pj , 1 ≤ i < j ≤ d, the d(d + 1)/2 edges of the simplex.

Mesh Quality – p. 251/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-347-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

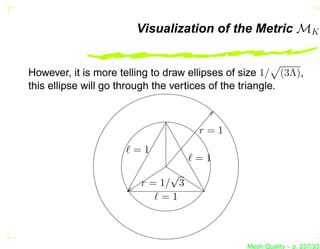

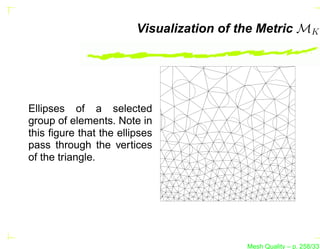

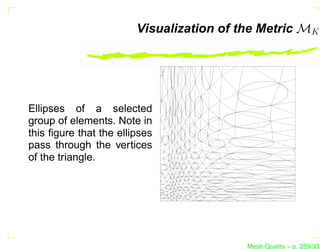

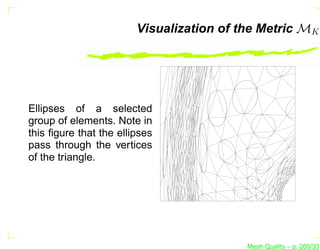

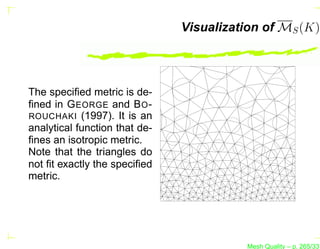

![Visualization of the Metric MK

It is usual to visualize the metric tensor as an ellipse.

Indeed, the metric tensor can be written as

MK = R−1 (θ) Λ R(θ), where the matrix Λ is the diagonal

matrix of the eigenvalues of MK , i.e., Λ = diag(λ1 , λ2 [, λ3 ]).

The eigenvalues λi are the length of the axes of the ellipse

and θ is the rotation matrix of the ellipse about the origin.

Mesh Quality – p. 256/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-352-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

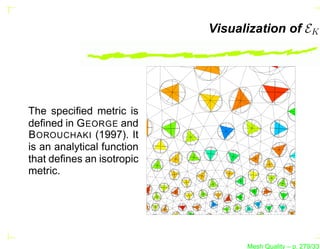

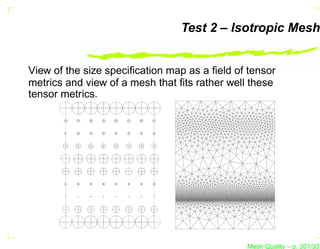

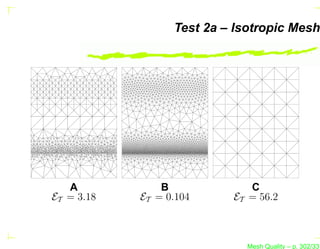

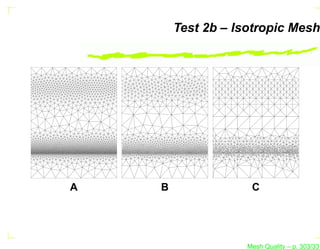

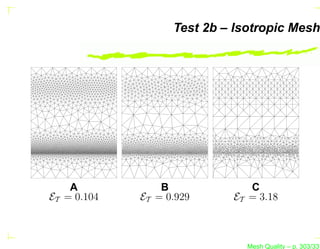

![Test 2 – Isotropic Mesh

This test case is defined in G EORGE and B OROUCHAKI

(1997).

The domain is a [0, 7] × [0, 9] rectangle.

This test case has an isotropic Riemannian metric defined

by :

h−2 (x, y)

1 0

MS = −2 ,...

0 h2 (x, y)

Mesh Quality – p. 299/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-396-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![Test 2 – Isotropic Mesh

. . . where h1 (x, y) = h2 (x, y) = h(x, y) is given by :

1 − 19y/40 if y ∈ [0, 2],

(2y−9)/5

20 if y ∈ ]2, 4.5],

h(x, y) =

5(9−2y)/5

if y ∈ ]4.5, 7],

1 4 y−7 4

+

5 5 2

if y ∈ ]7, 9].

Mesh Quality – p. 300/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-397-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

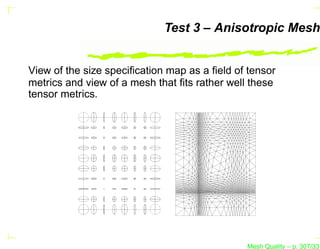

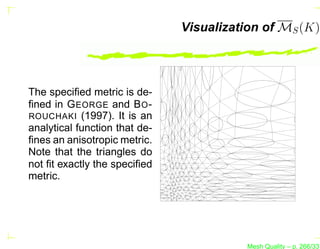

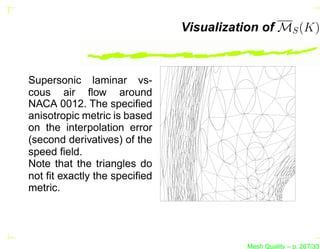

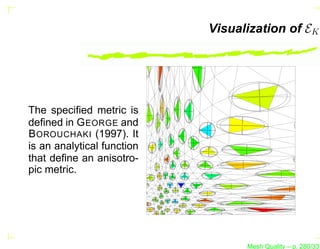

![Test 3 – Anisotropic Mesh

This test case is defined in G EORGE and B OROUCHAKI

(1997).

The domain is a [0, 7] × [0, 9] rectangle.

This test case has an anisotropic Riemannian metric

defined by :

h−2 (x, y)

1 0

MS = ,...

0 h−2 (x, y)

2

Mesh Quality – p. 304/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-403-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![Test 3 – Anisotropic Mesh

. . . where h1 (x, y) is given by :

1 − 19x/40

if x ∈ [0, 2],

(2x−7)/3

20 if x ∈ ]2, 3.5],

h1 (x, y) =

5(7−2x)/3

if x ∈ ]3.5, 5],

1 4 x−5 4

5

+5 2 if x ∈ ]5, 7], . . .

Mesh Quality – p. 305/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-404-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)

![Test 3 – Anisotropic Mesh

. . . and h2 (x, y) is given by :

1 − 19y/40

if y ∈ [0, 2],

(2y−9)/5

20 if y ∈ ]2, 4.5],

h2 (x, y) =

5(9−2y)/5

if y ∈ ]4.5, 7],

1 4 y−7 4

5

+5 2 if y ∈ ]7, 9].

Mesh Quality – p. 306/331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/meshqualityenglish-13172734628063-phpapp02-110929002759-phpapp02/85/Mesh-Quality-405-320.jpg?cb=1317257863)