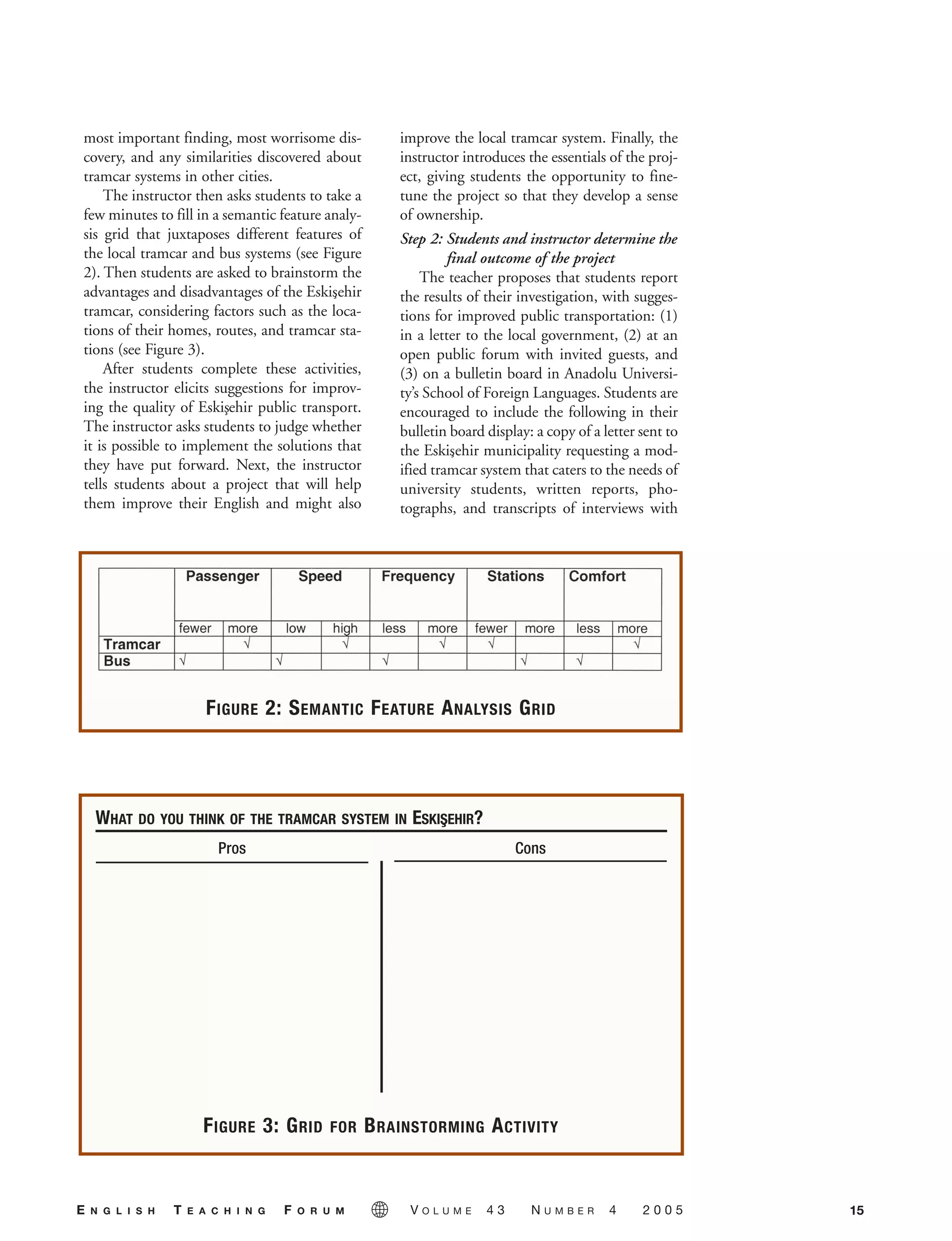

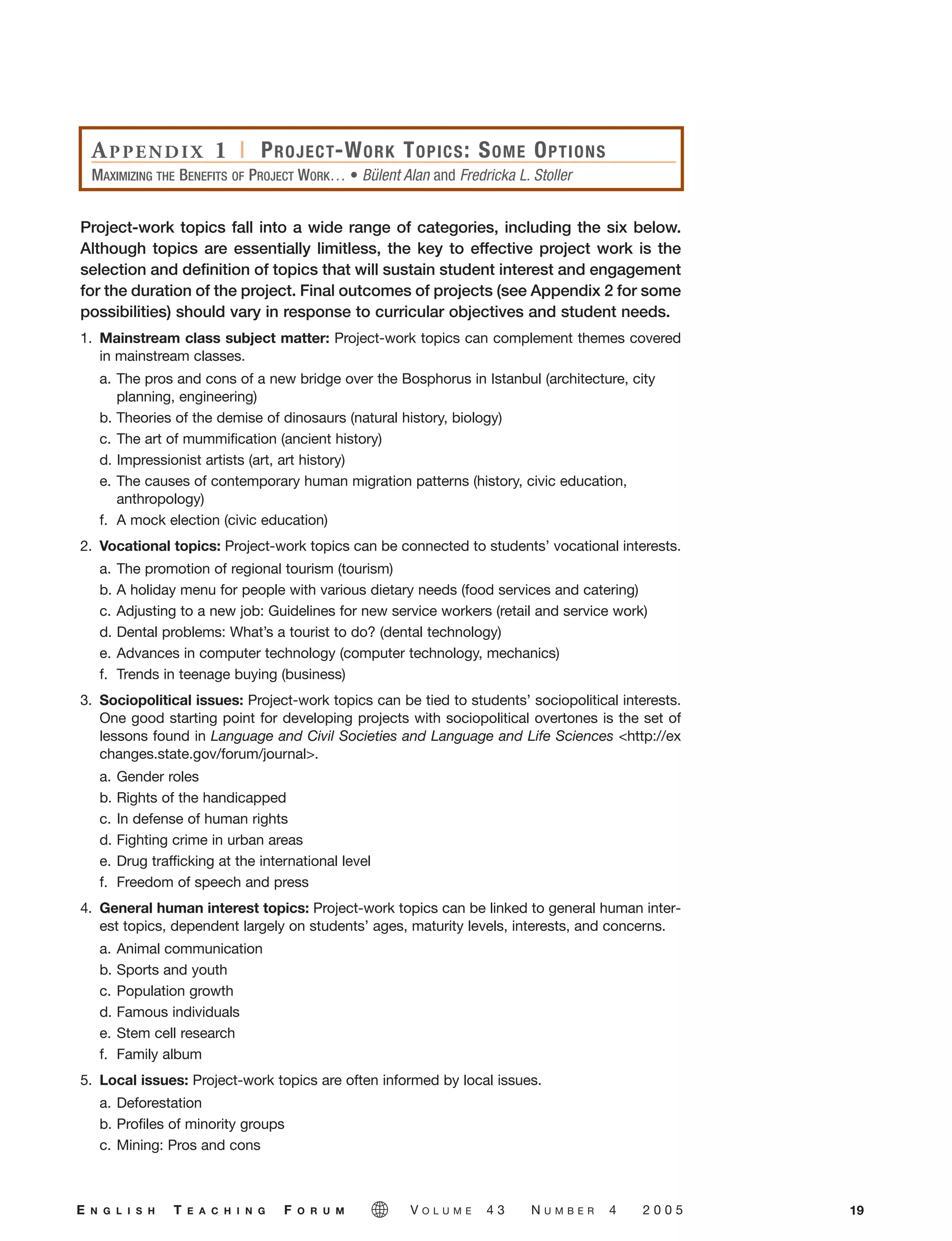

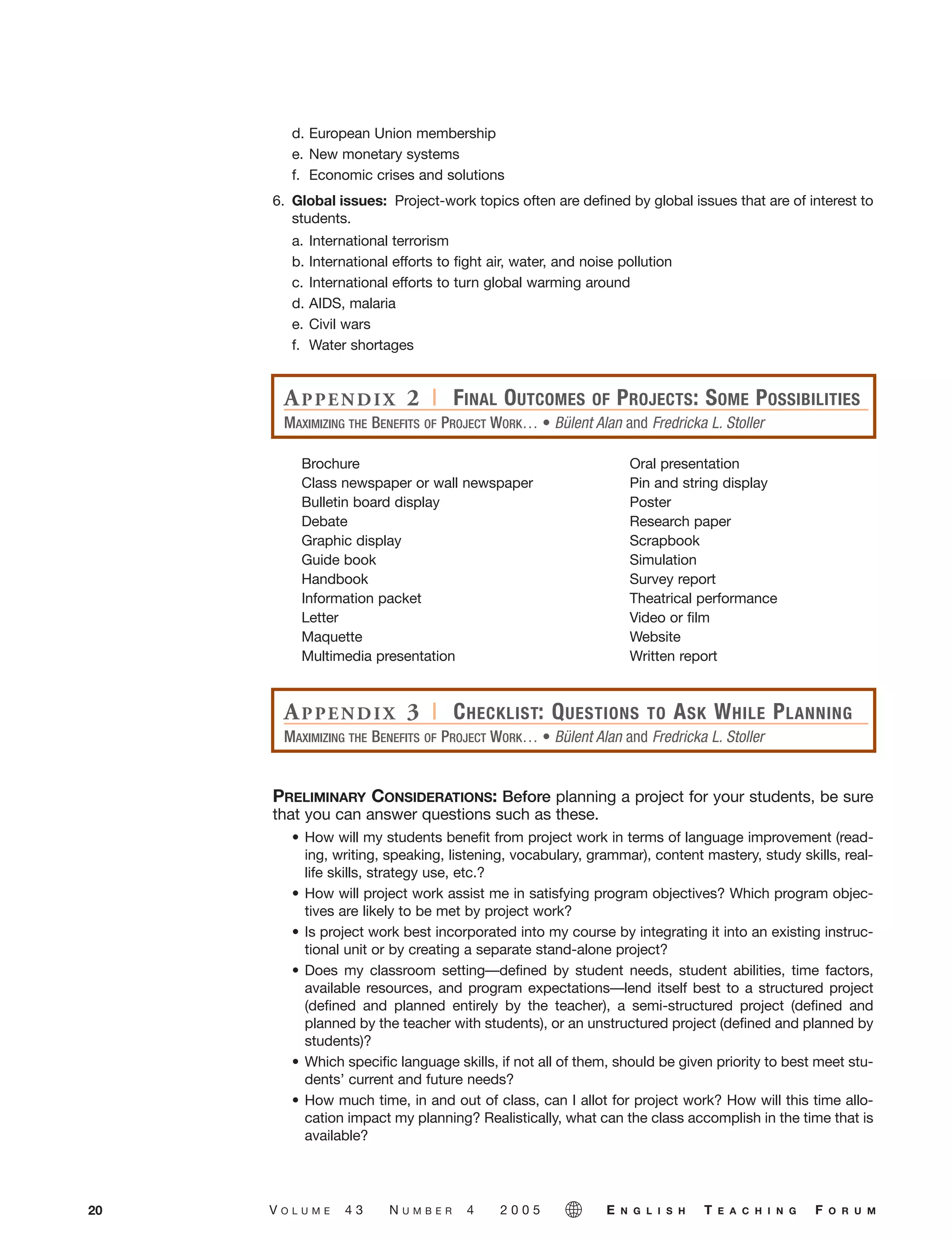

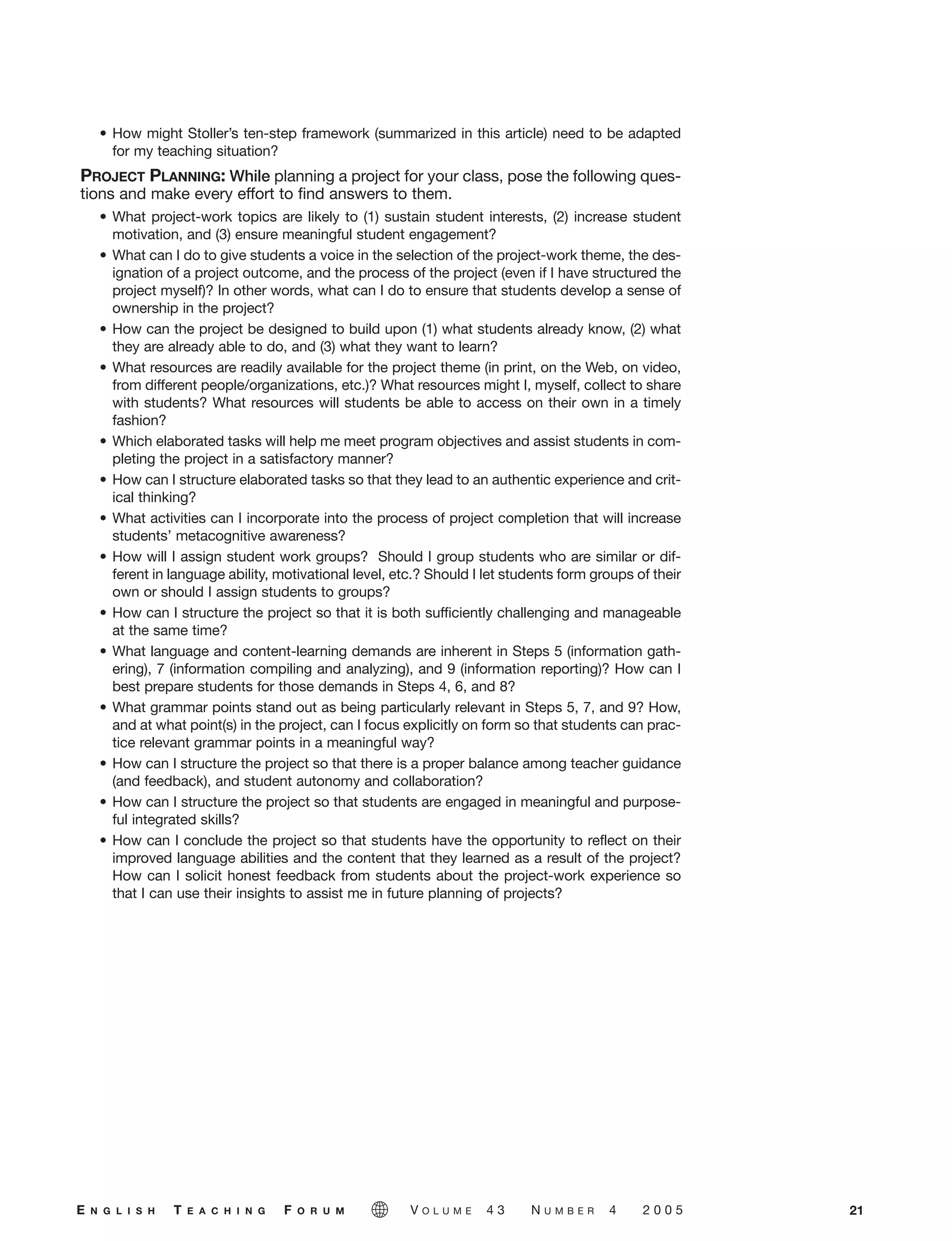

The document discusses maximizing the benefits of project work in foreign language classrooms. It describes how project work is sometimes implemented in ways that do not fully realize its potential benefits. Truly effective project work requires elaborate, multi-step tasks over an extended period that engage students in information gathering, processing, and reporting. This leads to increased content knowledge and language mastery. The article then outlines 10 steps for implementing project work that maximizes these benefits, including agreeing on a theme, determining outcomes, structuring tasks, gathering and analyzing information, and presenting and evaluating the project. An example project assessing the local tramcar system in Turkey is provided.