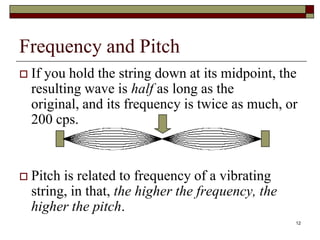

Mathematics and music are deeply linked. Pythagoras first discovered mathematical relationships between string lengths and musical pitches. Since then, theorists have studied proportions and how different frequencies produce different notes. Sound is produced by regular vibrations, with pitch determined by frequency. Overtones above the fundamental frequency give instruments their distinctive timbre. Resonant frequencies are important in acoustics and engineering.

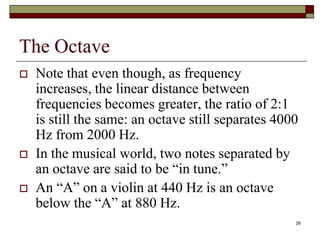

![Galileo and Mersenne

Both Galileo Galilei [1564-1642] and Marin

Mersenne [1588-1648] studied sound.

Galileo elevated the study of vibrations and

the correlation between pitch and frequency

of the sound source to scientific standards.

His interest in sound was inspired by his

father, who was a

mathematician, musician, and composer.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mathmusic-111120113405-phpapp01/85/Math-and-music-9-320.jpg)