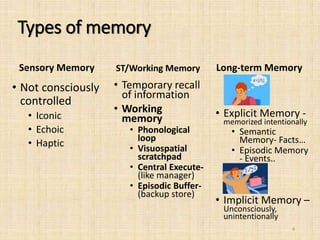

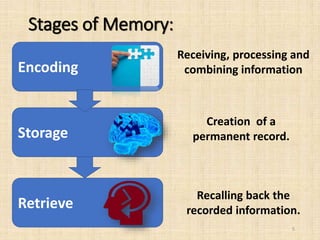

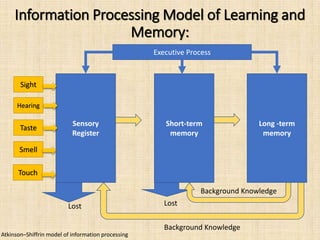

Memory is the ability to acquire, store, retain, and retrieve information over time. There are three main types of memory: sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Memory involves three stages - encoding, where information is received and processed; storage, where a permanent record is created; and retrieval, where the stored information is recalled. Patterns of encoding, storage, and retrieval include visual, acoustic, elaborative, semantic, short-term versus long-term storage, and different types of recall. Information processing models show how sensory information moves through sensory registers, short-term memory, and is either lost or consolidated into long-term memory with the help of background knowledge and executive processes.