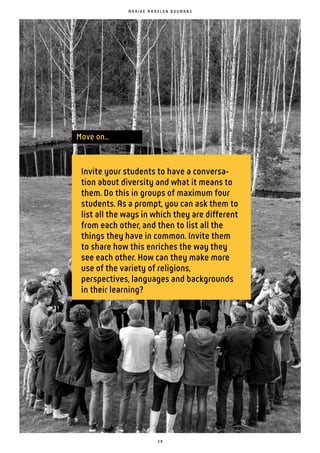

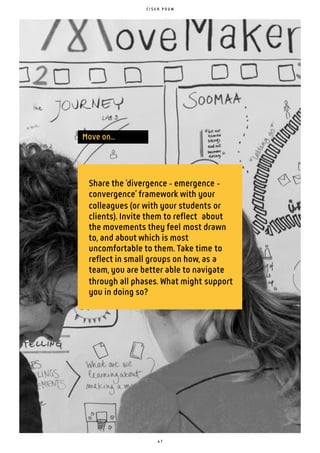

This book was co-created by a group of educators called MoveMakers during a three-day book sprint. It contains 11 articles by MoveMakers sharing insights and experiences from their 18-month learning journey. The book aims to inspire readers to shake up education and support new ways of learning. It was written collaboratively in an experimental way to model new approaches to learning. The diverse articles explore topics like innovation in education, learning design, diversity, movement in learning, and personal leadership. The book is intended as an ongoing conversation to spark new thinking about education.