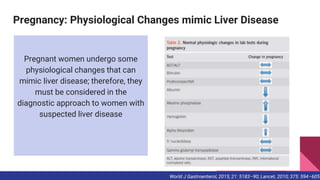

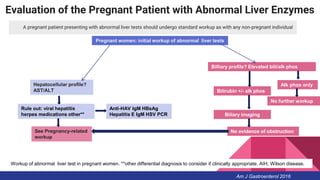

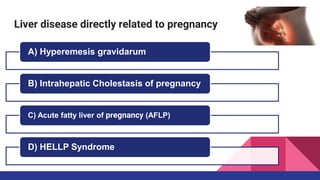

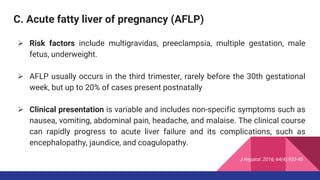

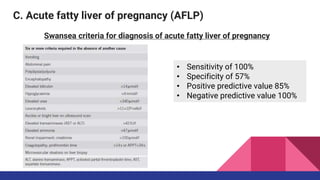

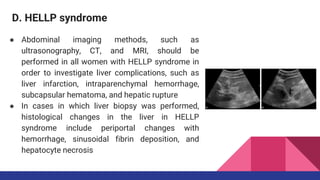

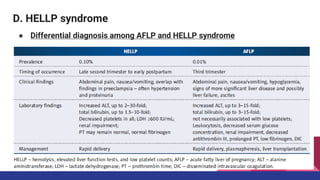

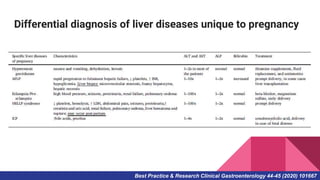

The document discusses liver disorders that can occur during pregnancy. It describes how physiological changes during pregnancy can mimic liver disease, and identifies two main categories of pregnancy-related liver disease: 1) diseases directly related to pregnancy, including hyperemesis gravidarum, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, and HELLP syndrome; and 2) diseases not directly related to pregnancy like cirrhosis or viral hepatitis. The document provides details on diagnostic approaches and management considerations for evaluating and treating common liver diseases that can develop during pregnancy.