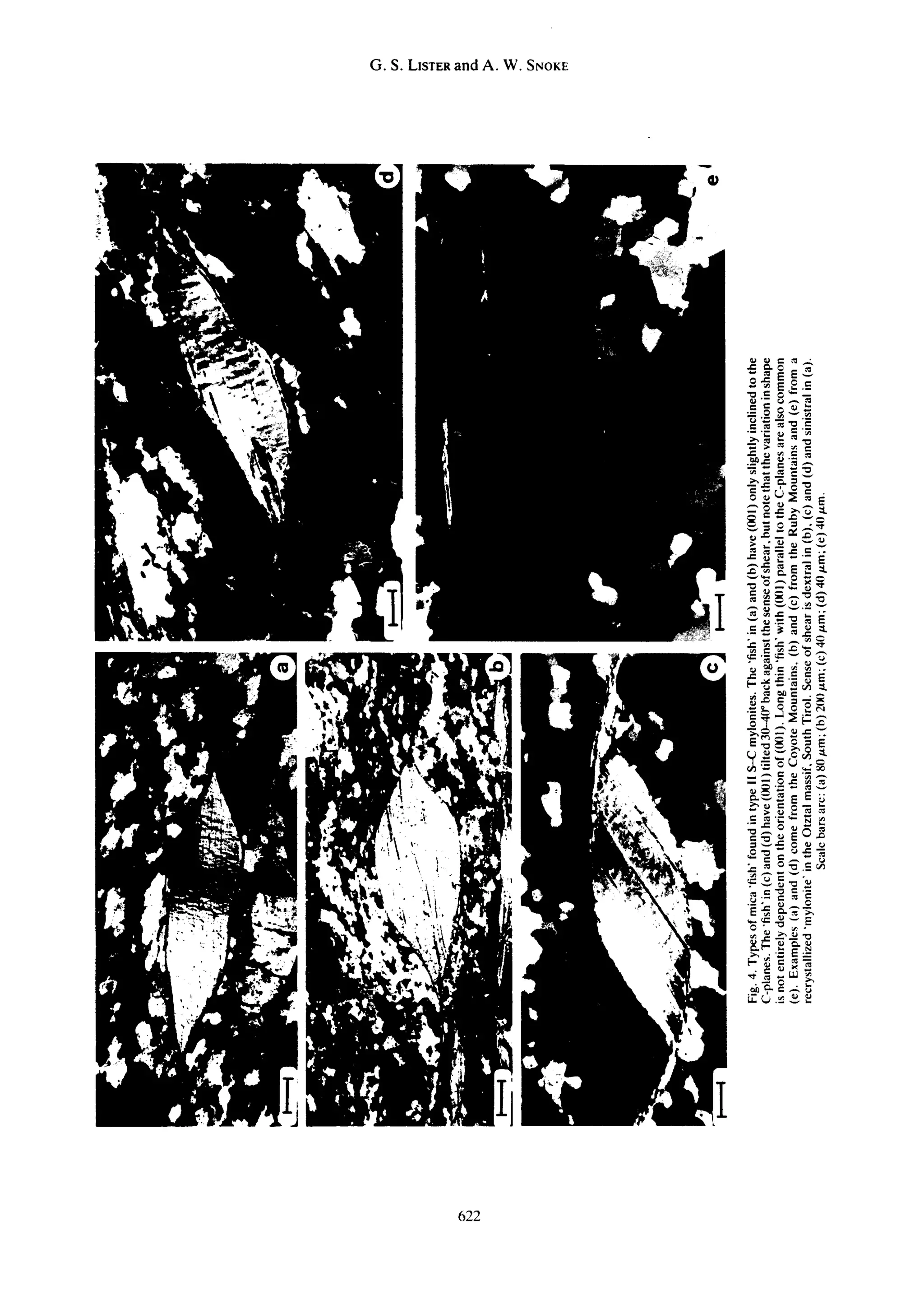

This document describes two types of S-C mylonites:

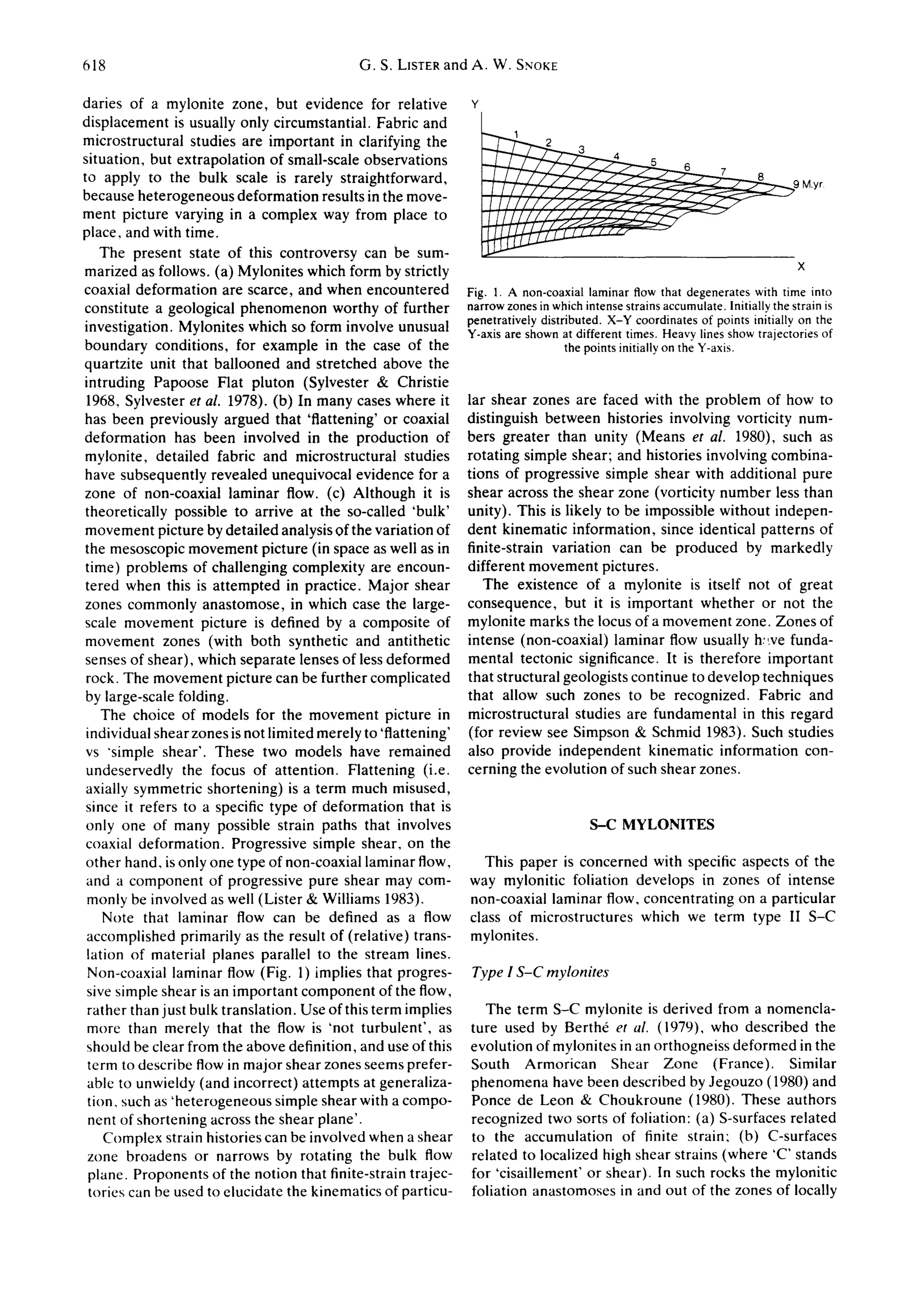

Type I S-C mylonites involve narrow zones of intense shear strain that cut across a pre-existing mylonitic foliation. They typically occur in deformed granitoids.

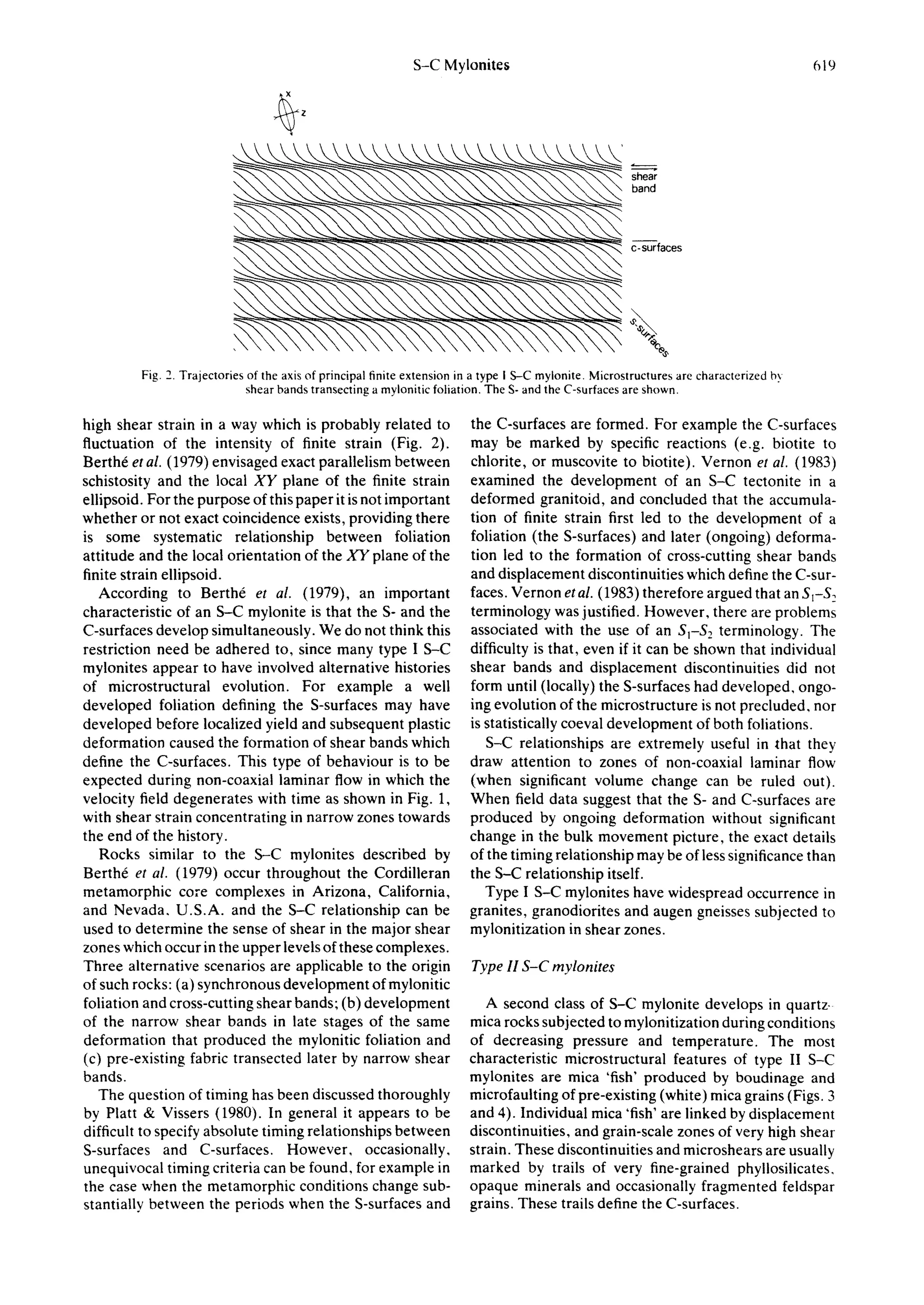

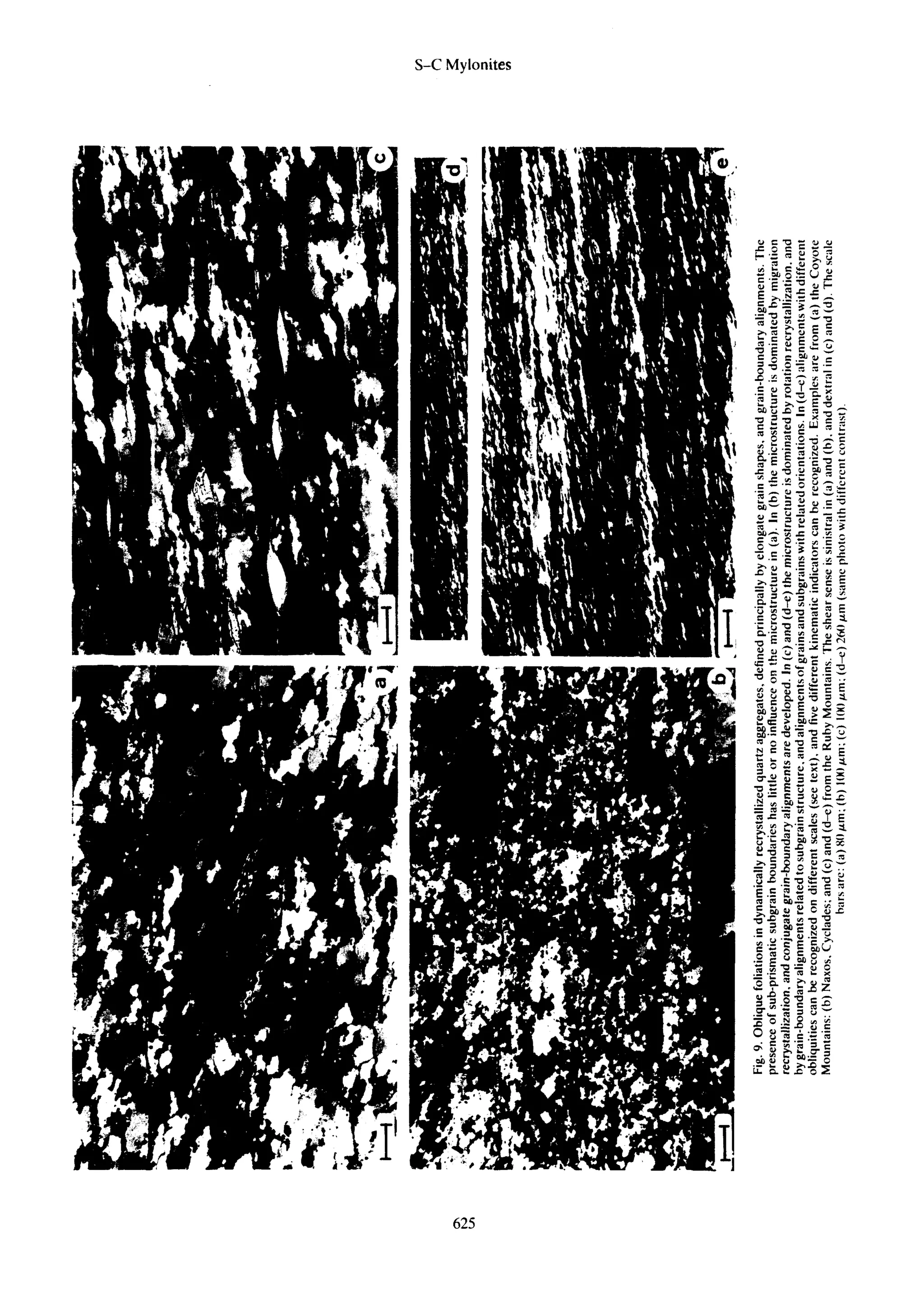

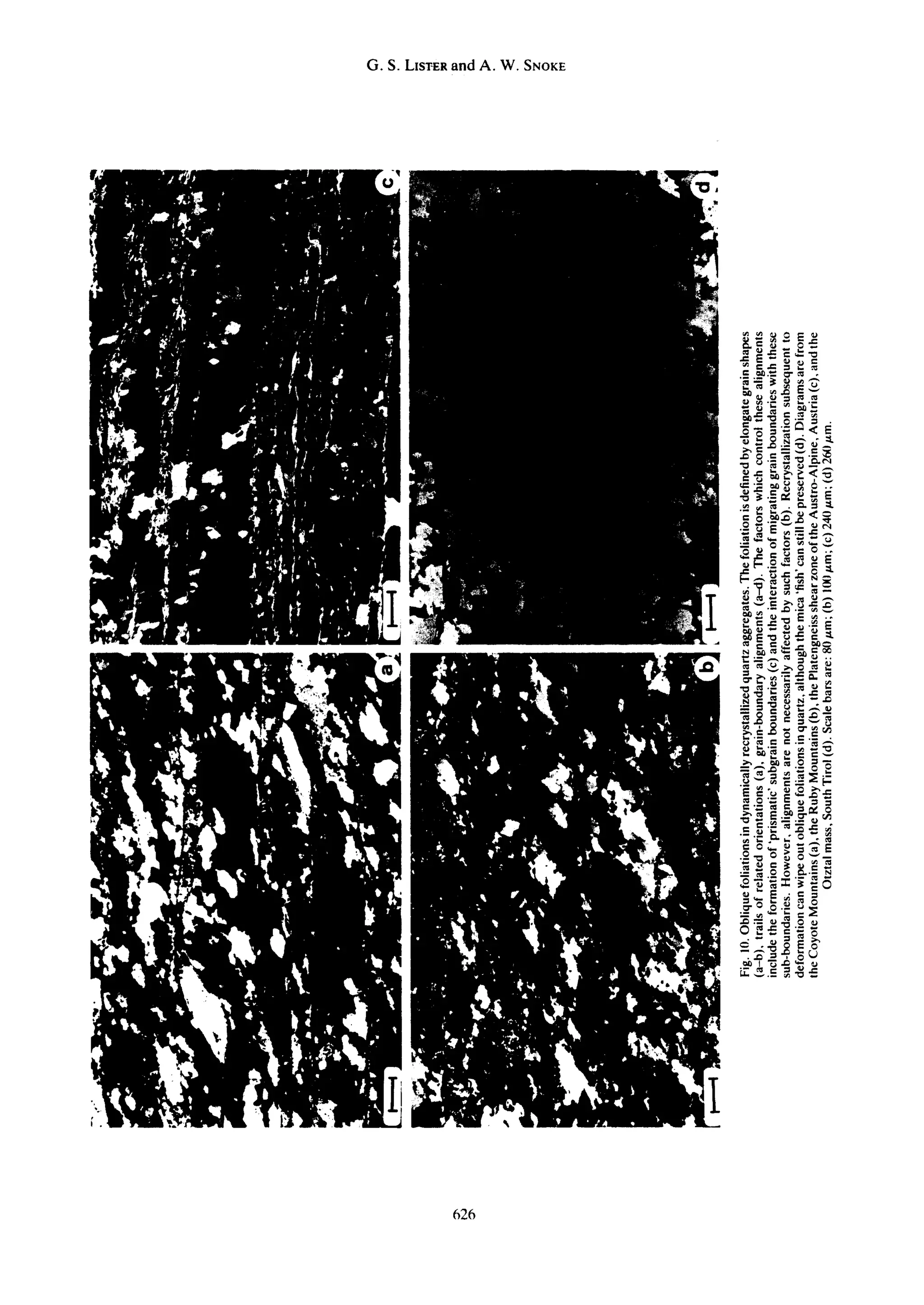

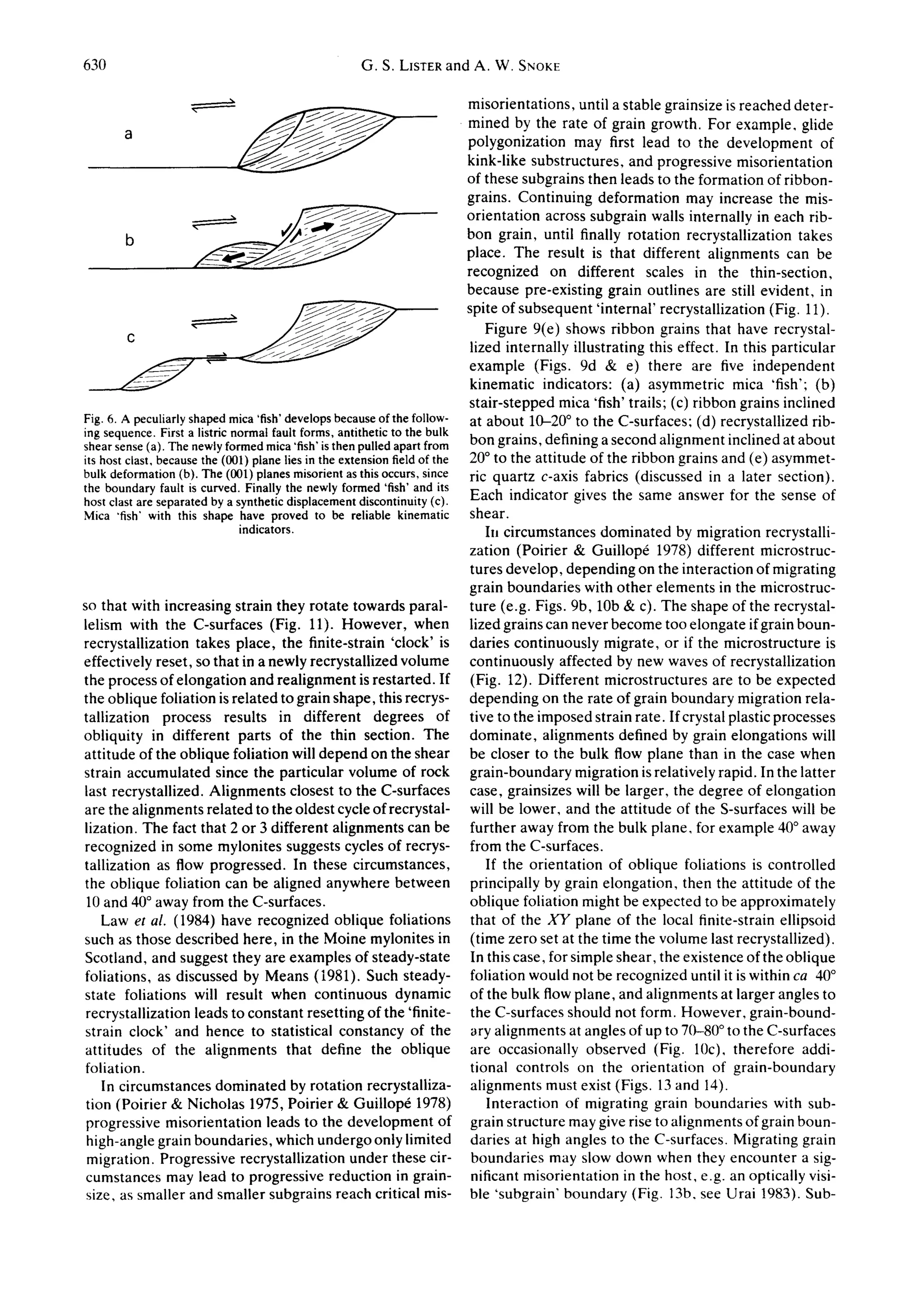

Type II S-C mylonites have more widespread occurrence in quartz-mica rocks subjected to intense non-coaxial laminar flow. The C-surfaces are defined by trails of mica "fish" formed by microscopic displacement discontinuities or zones of very high shear strain. The S-surfaces are defined by oblique foliations in adjacent quartz aggregates formed by dynamic recrystallization.