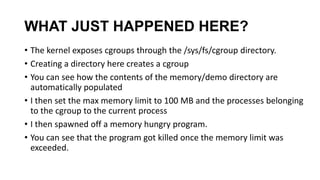

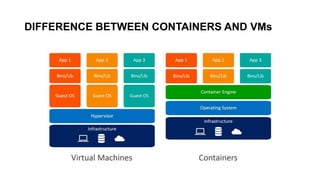

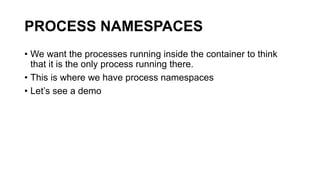

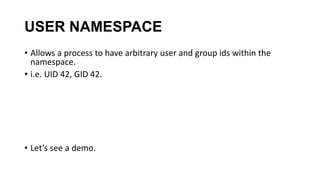

The document discusses the key concepts behind Linux containers including namespaces and cgroups. It begins with an overview of containers and how they provide isolation compared to virtual machines. It then covers the various Linux namespaces (process, user, UTS, mount, network) and how they isolate different aspects like processes, users, hostnames etc. It demonstrates creating namespaces using Golang. It also discusses cgroups and how they are used to control resource usage. The document provides code samples and explanations for many of the core Linux features that enable containerization.

![CONTAINERS

• Quick intro

• A logical way to package

applications

• Provides isolated execution

environments

• Composable

• Portable

# Example Dockerfile

FROM ubuntu

MAINTAINER asbilgi@microsoft.com

RUN apt-get update

RUN apt-get install –y python

CMD [/bin/bash]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linuxcontainerinternals-191206230738/85/Linux-container-internals-9-320.jpg)

![USER NAMESPACE

cmd.SysProcAttr = &syscall.SysProcAttr{

Cloneflags: syscall.CLONE_NEWPID | syscall.CLONE_NEWUSER,

UidMappings: []syscall.SysProcIDMap{

{

ContainerID: 42,

HostID: os.Getuid(),

Size: 1,

},

},

GidMappings: []syscall.SysProcIDMap{

{

ContainerID: 42,

HostID: os.Getgid(),

Size: 1,

},

},

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/linuxcontainerinternals-191206230738/85/Linux-container-internals-39-320.jpg)