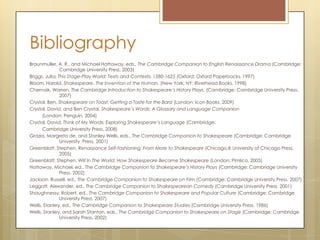

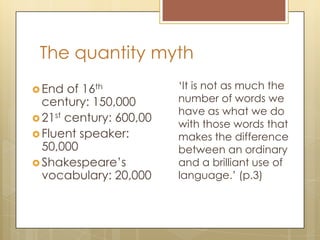

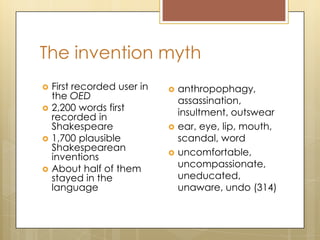

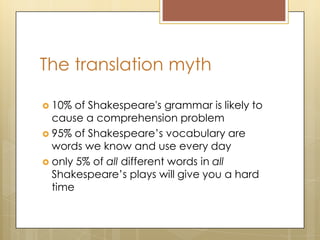

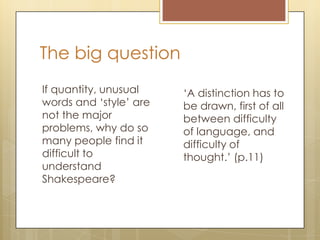

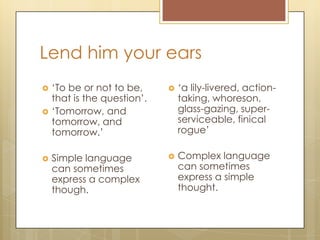

This document discusses Shakespeare's language and some common myths about it. It argues that Shakespeare's vocabulary was not unusually large, that he did not invent as many words as believed, and that his language is not as difficult to understand as thought. While Shakespeare used complex language at times, he also effectively conveyed complex ideas with simple language. Understanding the social and historical context as well as imaginative elements like metaphor are more important to comprehending Shakespeare than the specific words themselves. Studying Shakespeare's linguistic techniques can help increase readers' appreciation and understanding of his works.

![‘A study of [Shakespeare’s] linguistic

techniques, in such areas as functional shift,

affixation, idiomatic allusiveness and

collocation, can add to our awareness of the

language’s expressive potential and increase

our confidence as users. At the same time, of

course, the more we study Shakespeare from

a linguistic point of view, the more we will

increase our understanding and enjoyment

of the plays as literature and theatre.’

(Crystal, 2003)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lendmeyourears-130428093836-phpapp01/85/Lend-me-your-ears-23-320.jpg)