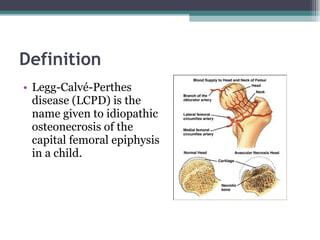

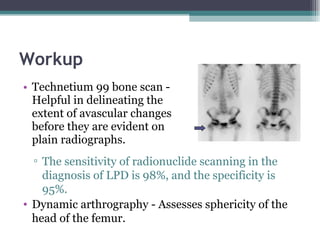

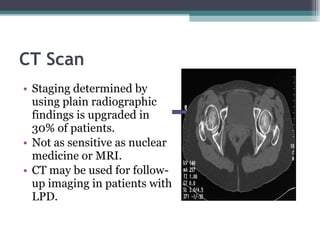

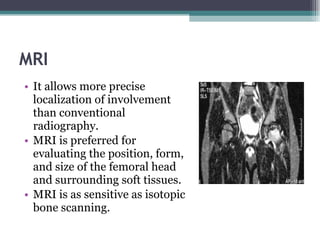

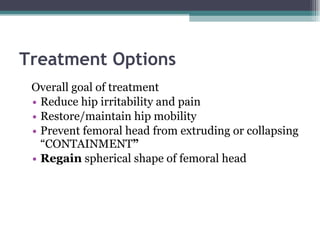

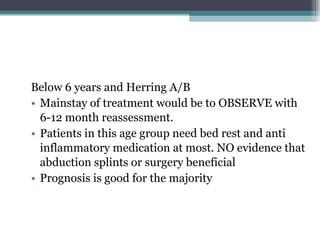

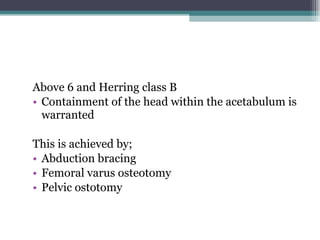

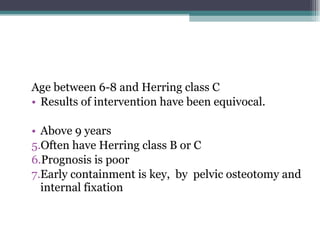

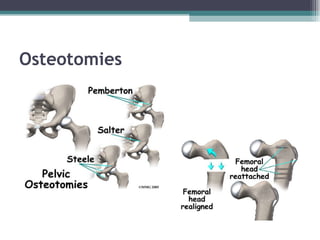

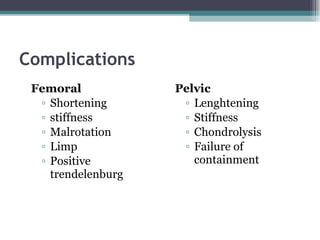

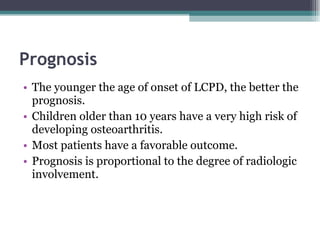

Legg Calve Perthes Disease (LCPD) is osteonecrosis of the femoral head that typically affects children between the ages of 4-10. For patients under 6 years old with minimal involvement, the prognosis is generally good and treatment involves rest and anti-inflammatories. For patients between 6-8 years old with more involvement, containment of the femoral head through bracing or surgery is often recommended. Patients presenting after age 9 usually have a poor prognosis due to more advanced involvement and are treated with early containment procedures, though stiffness can be a complication.