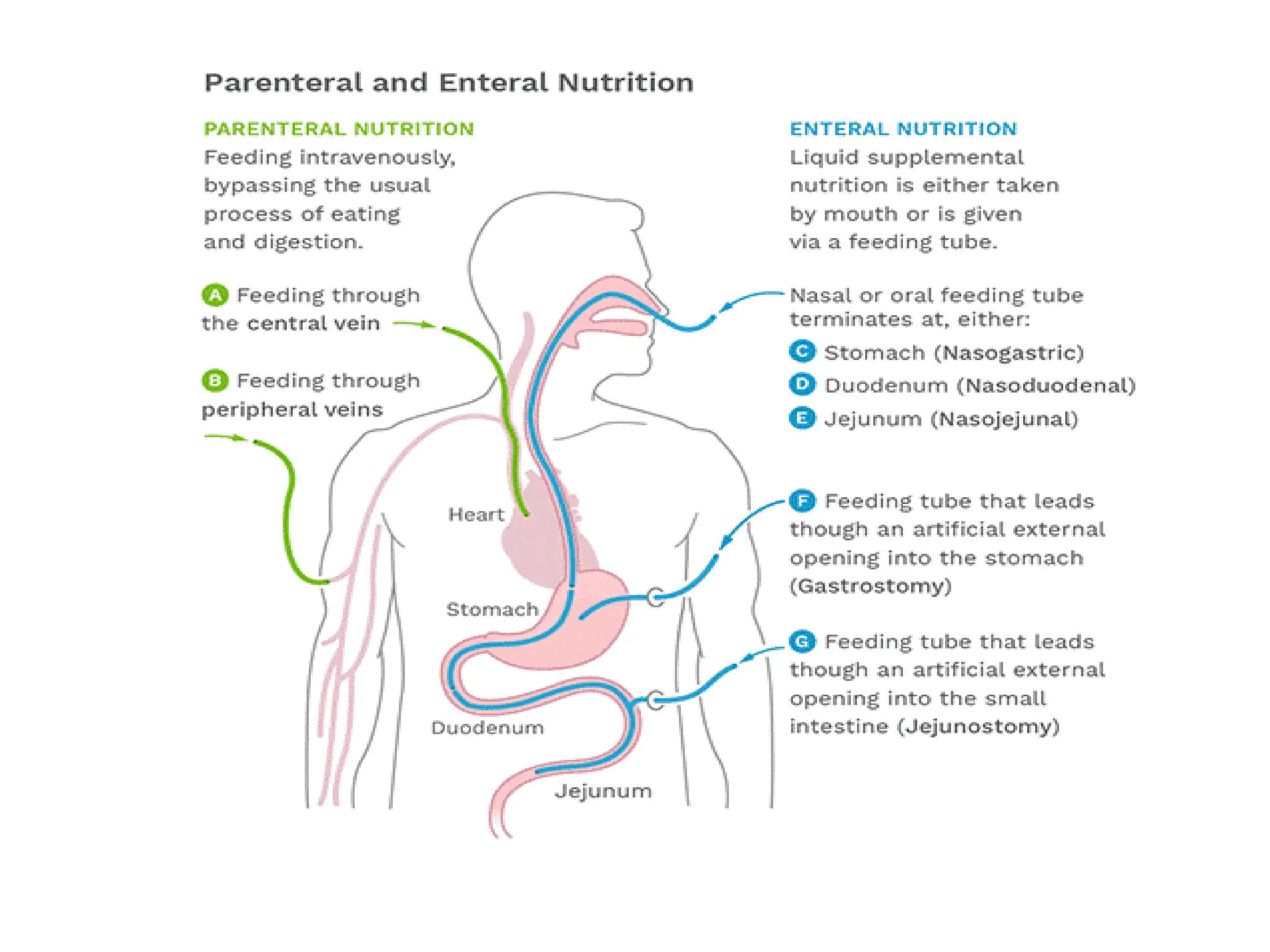

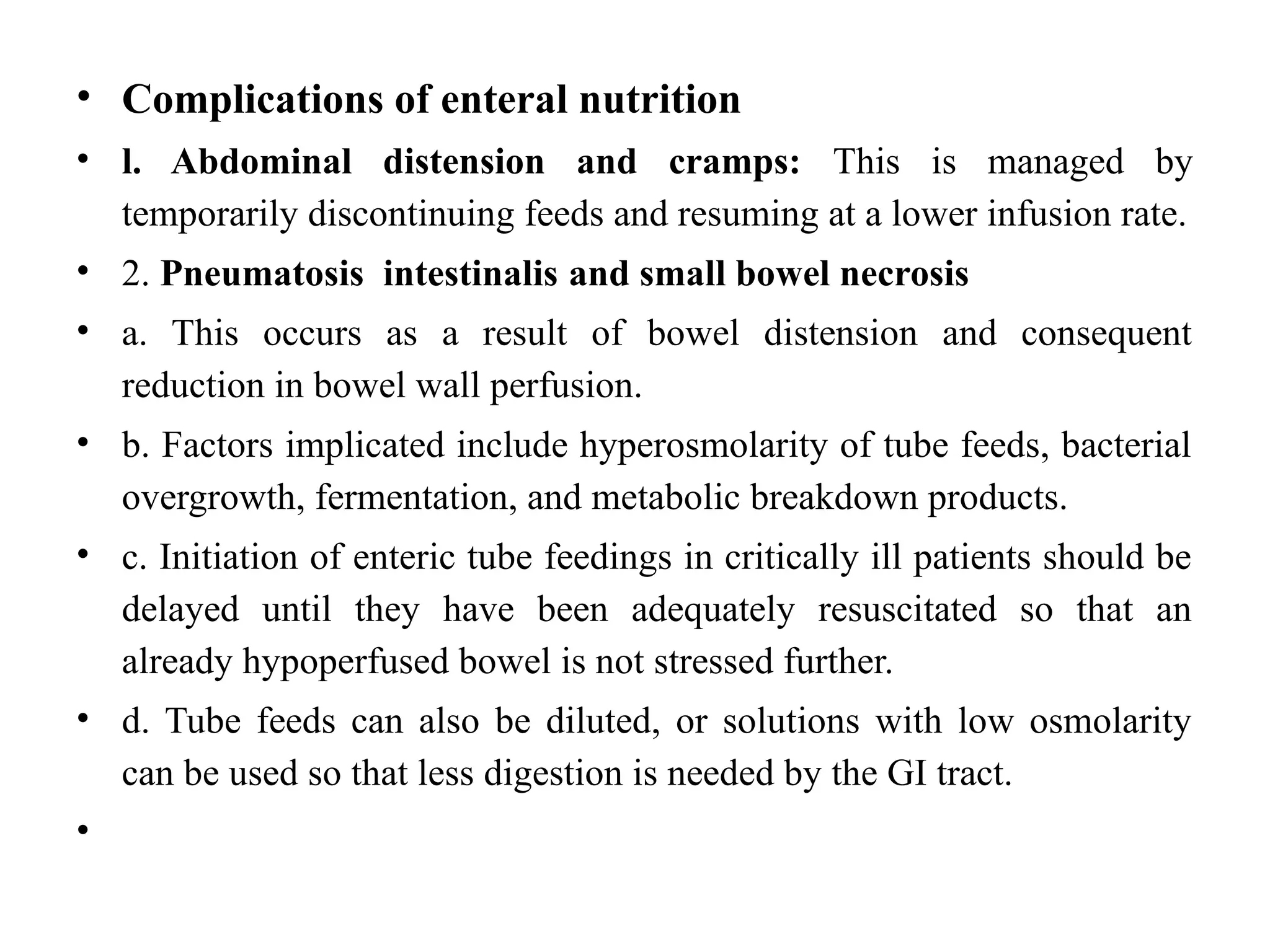

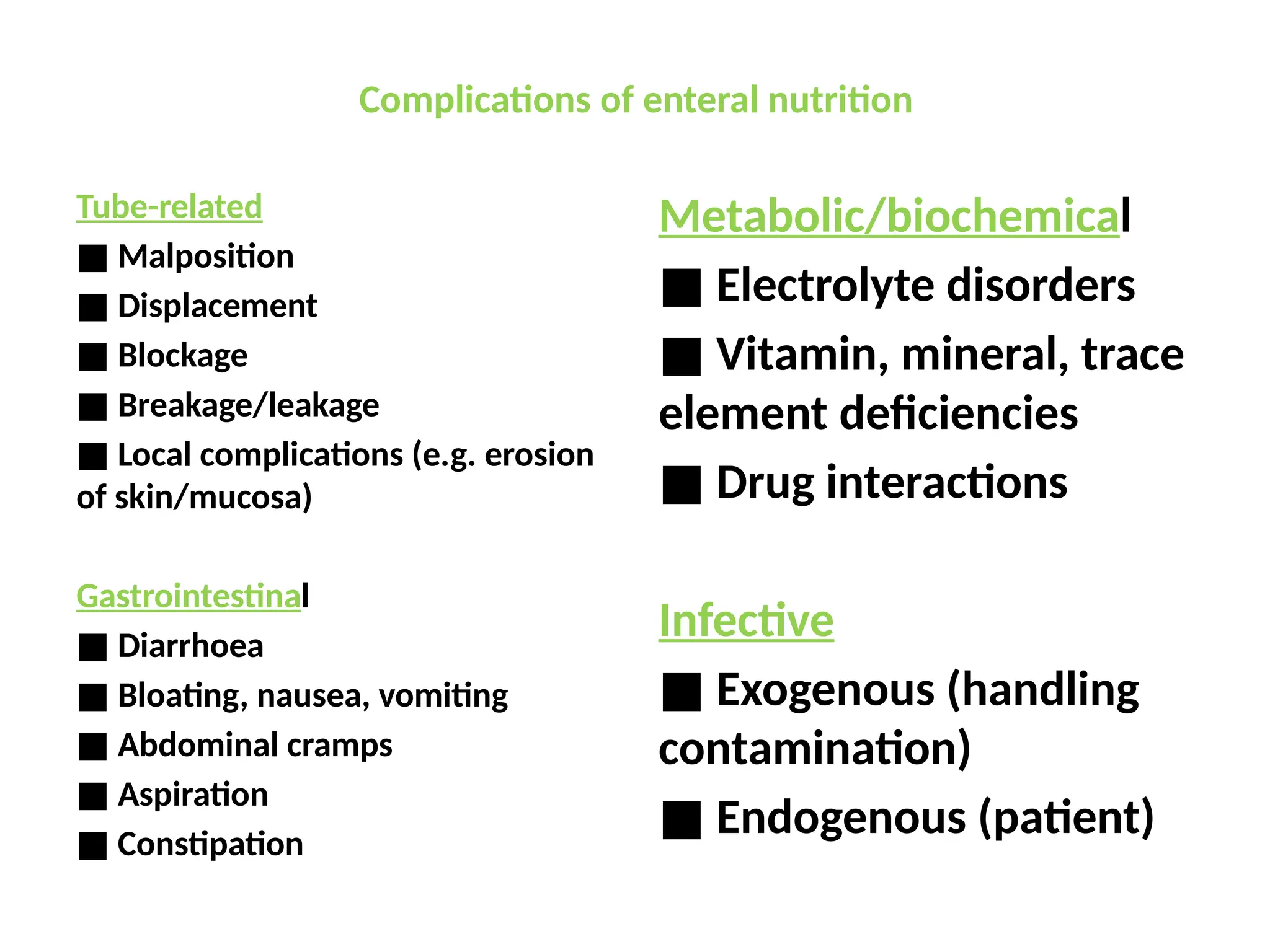

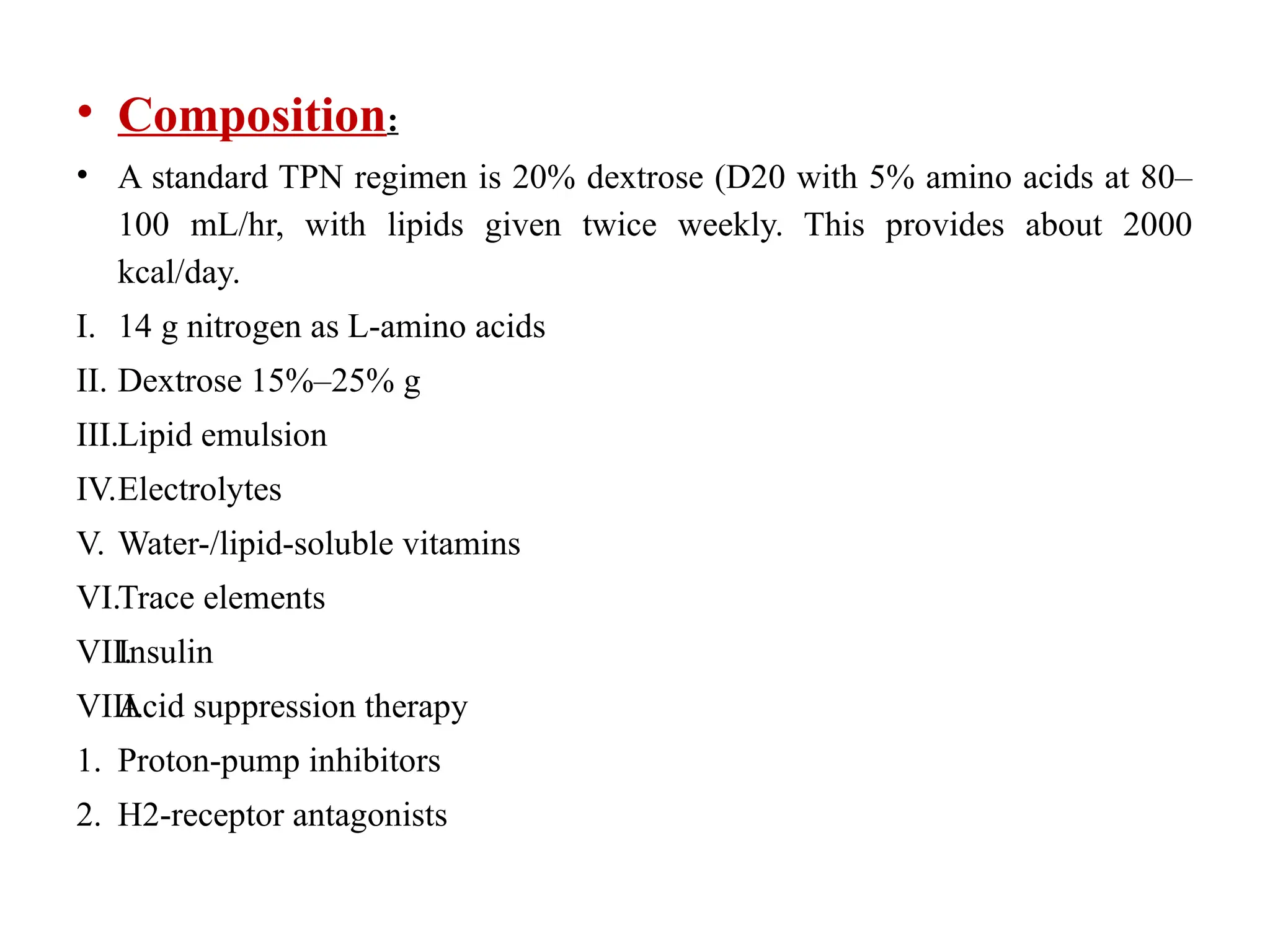

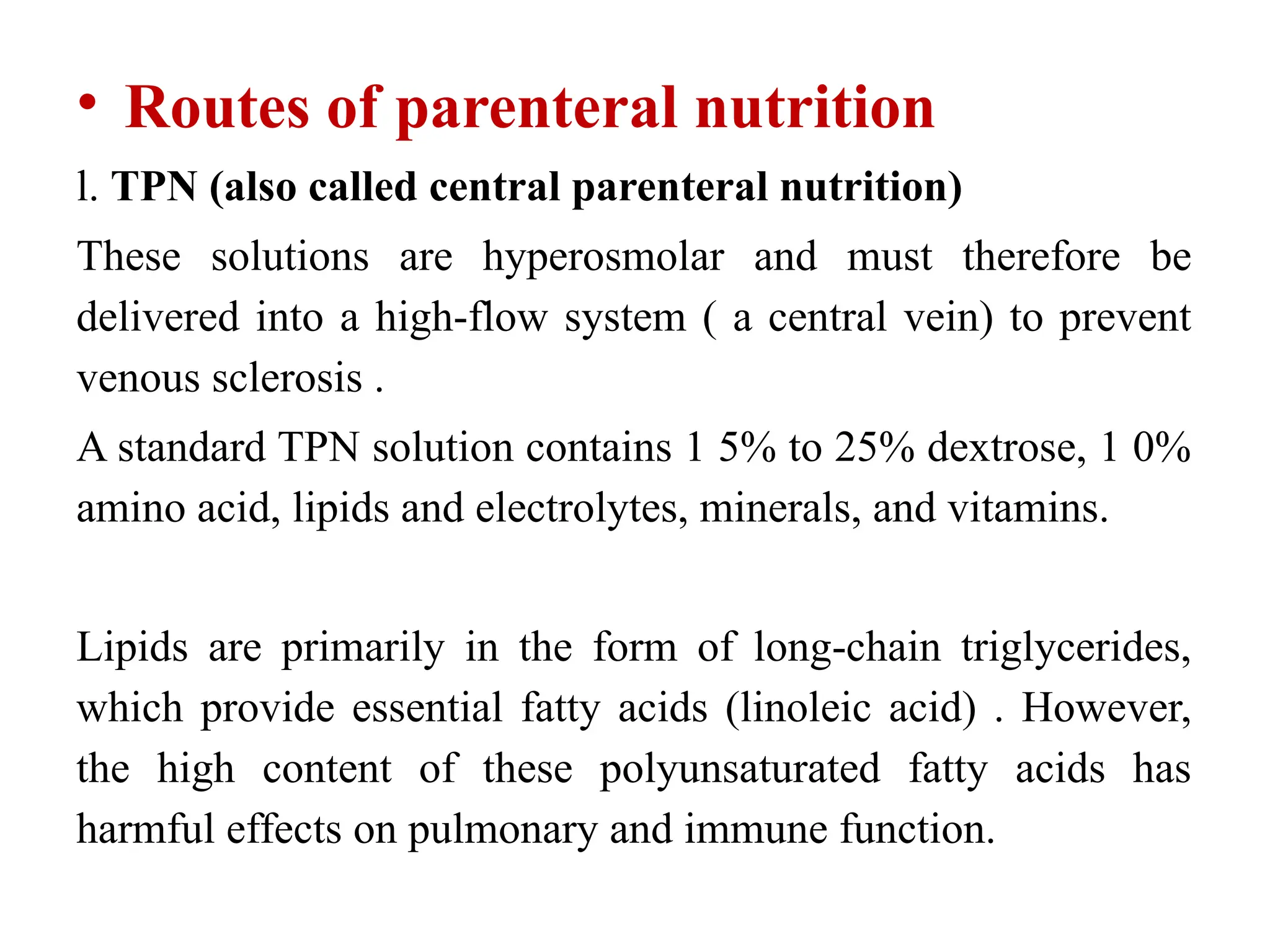

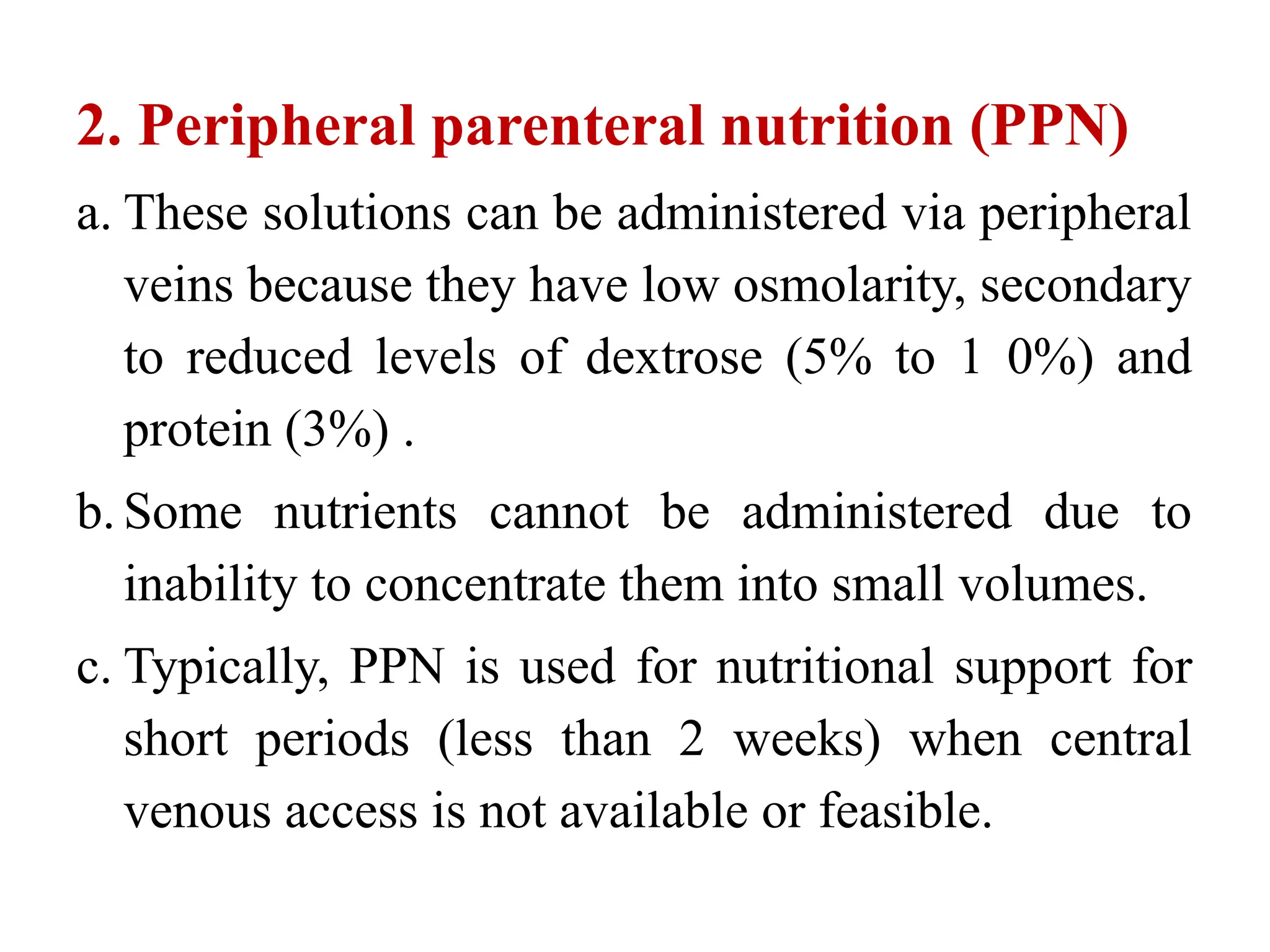

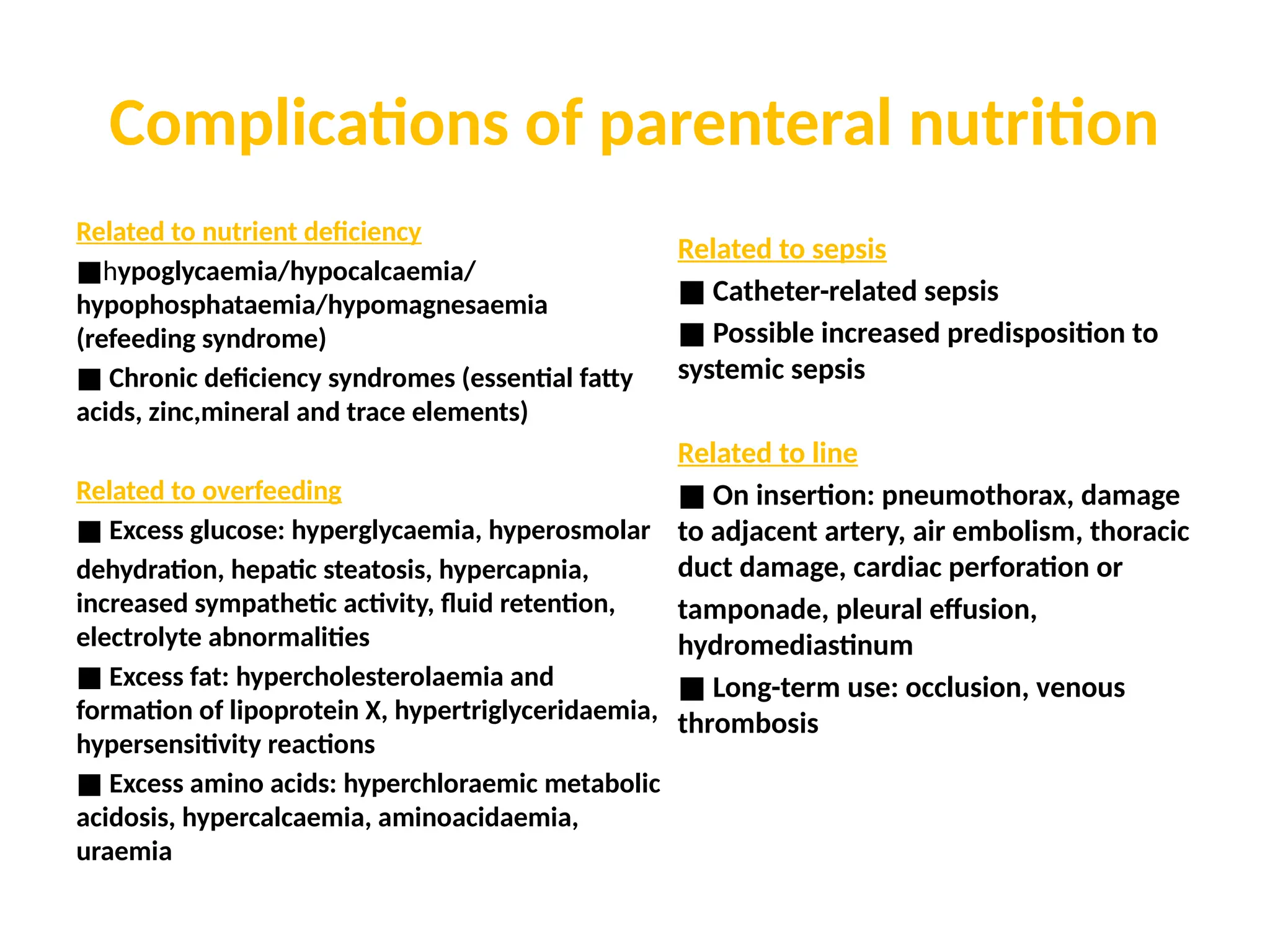

The document outlines the importance of nutritional support for surgical patients to counteract catabolic effects due to disease or injury, including methods for nutritional assessment and requirements for energy and protein intake. It emphasizes enteral nutrition as the preferred method, detailing various formulas for different patient conditions and providing guidance on administration techniques. Additionally, it covers parenteral nutrition, its indications, composition, routes, and related complications.