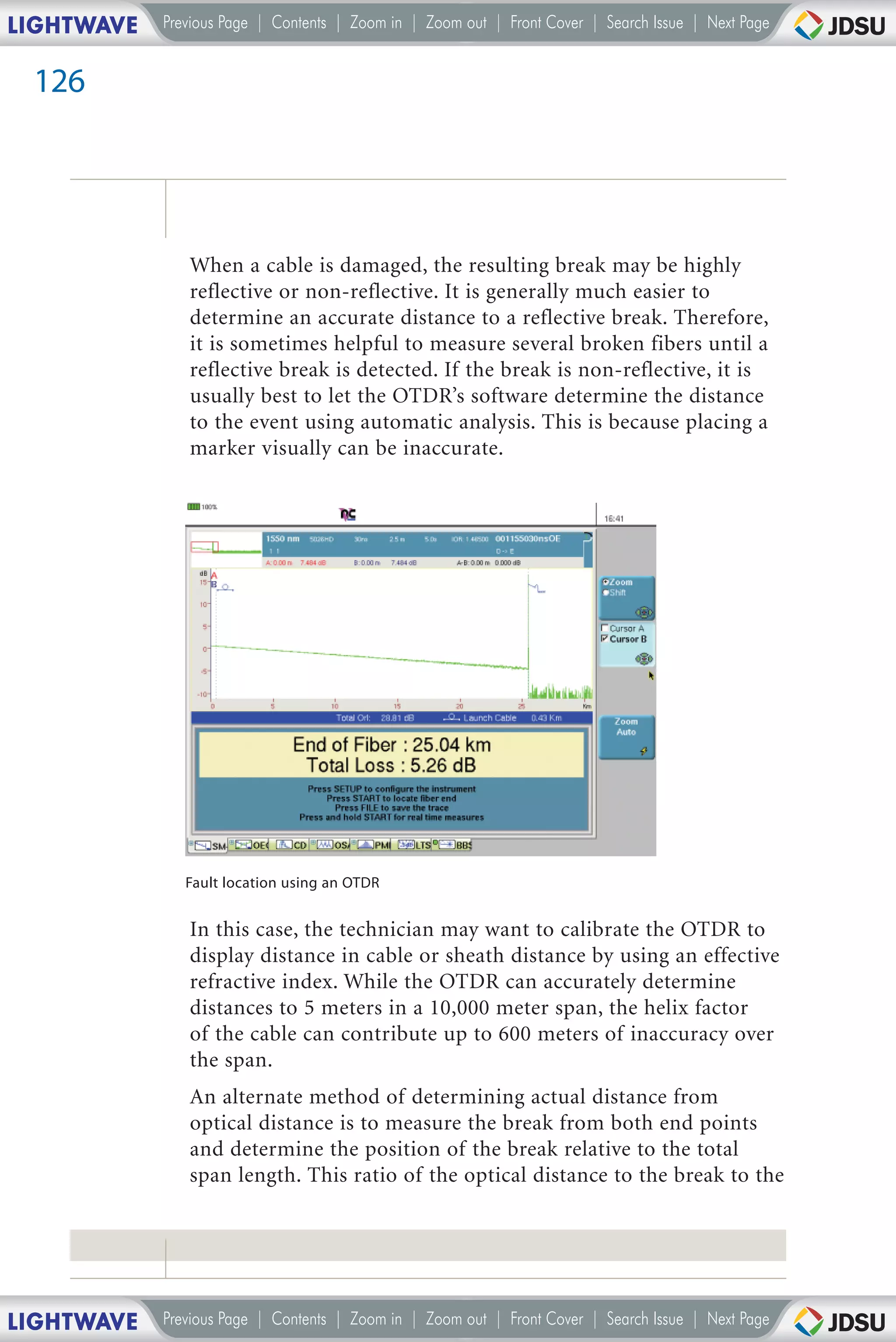

This document provides an overview and introduction to fiber optic testing and measurement. It discusses the basic principles of light transmission in optical fibers, including different fiber types, attenuation, dispersion, and other effects. It also describes common fiber optic test equipment used to measure insertion loss, return loss, and characterize fibers, such as light sources, power meters, loss test sets, optical time domain reflectometers (OTDRs), and monitoring systems. The document is intended to serve as a reference guide for fiber optic testing.

![LIGHTWAVE Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page

111

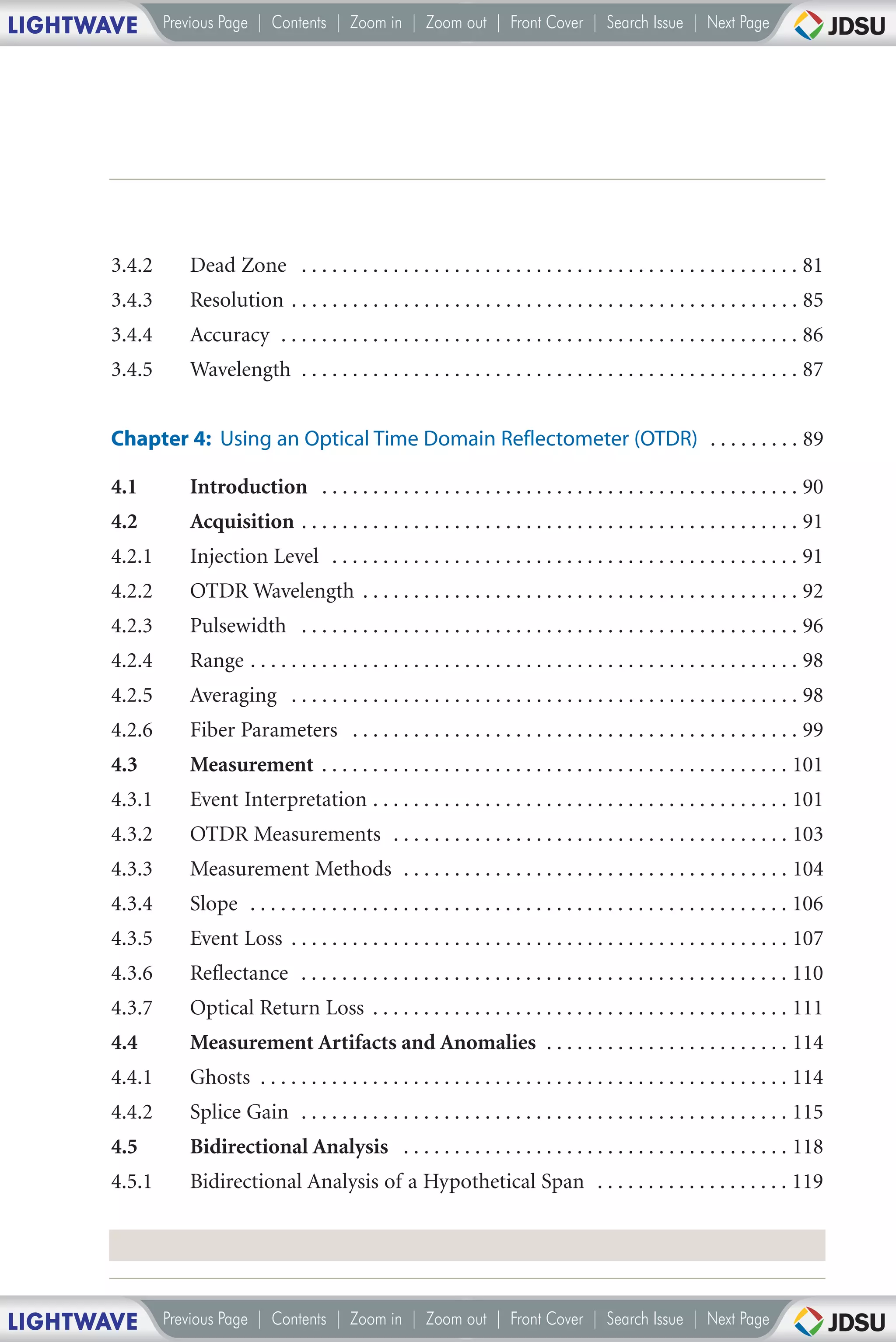

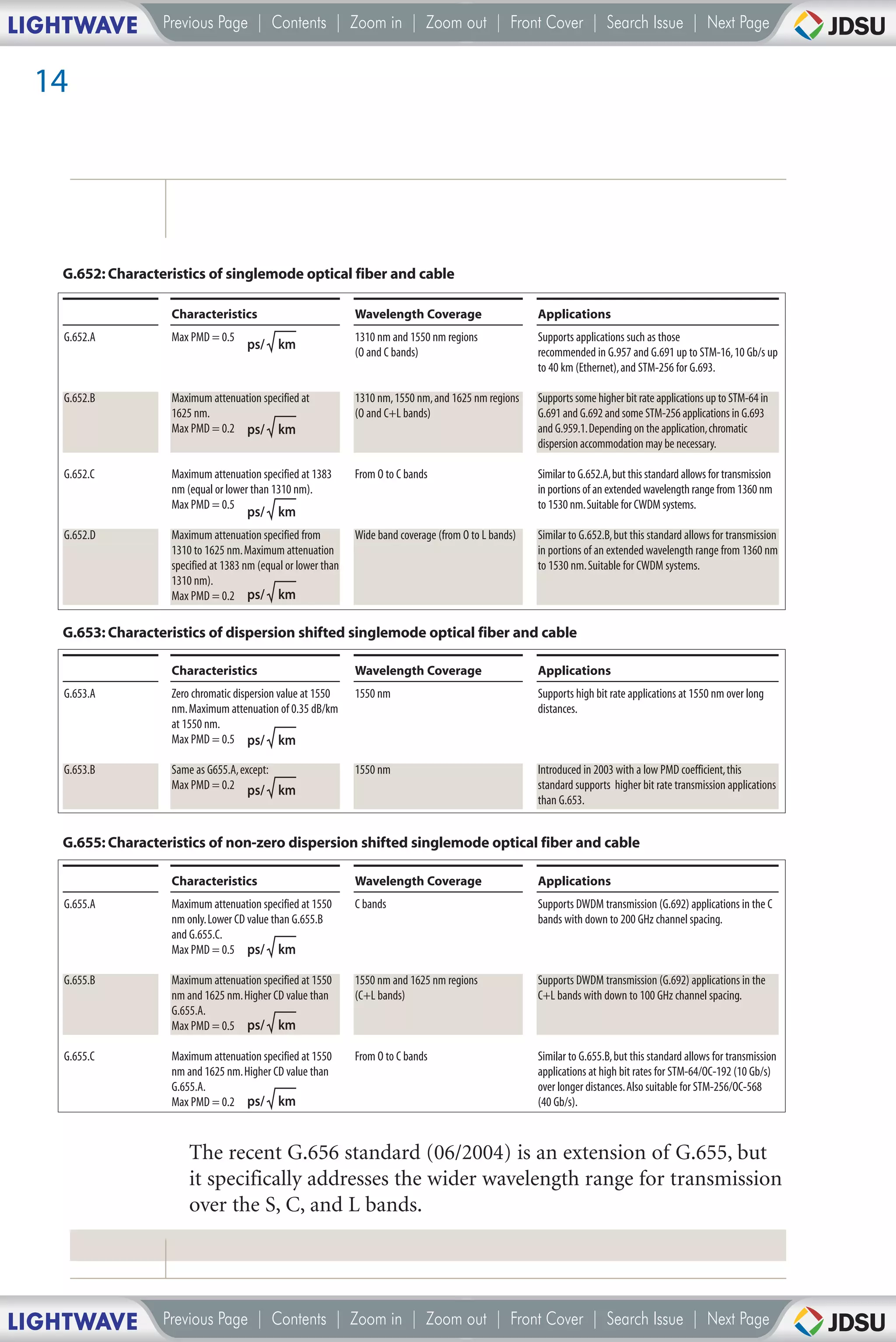

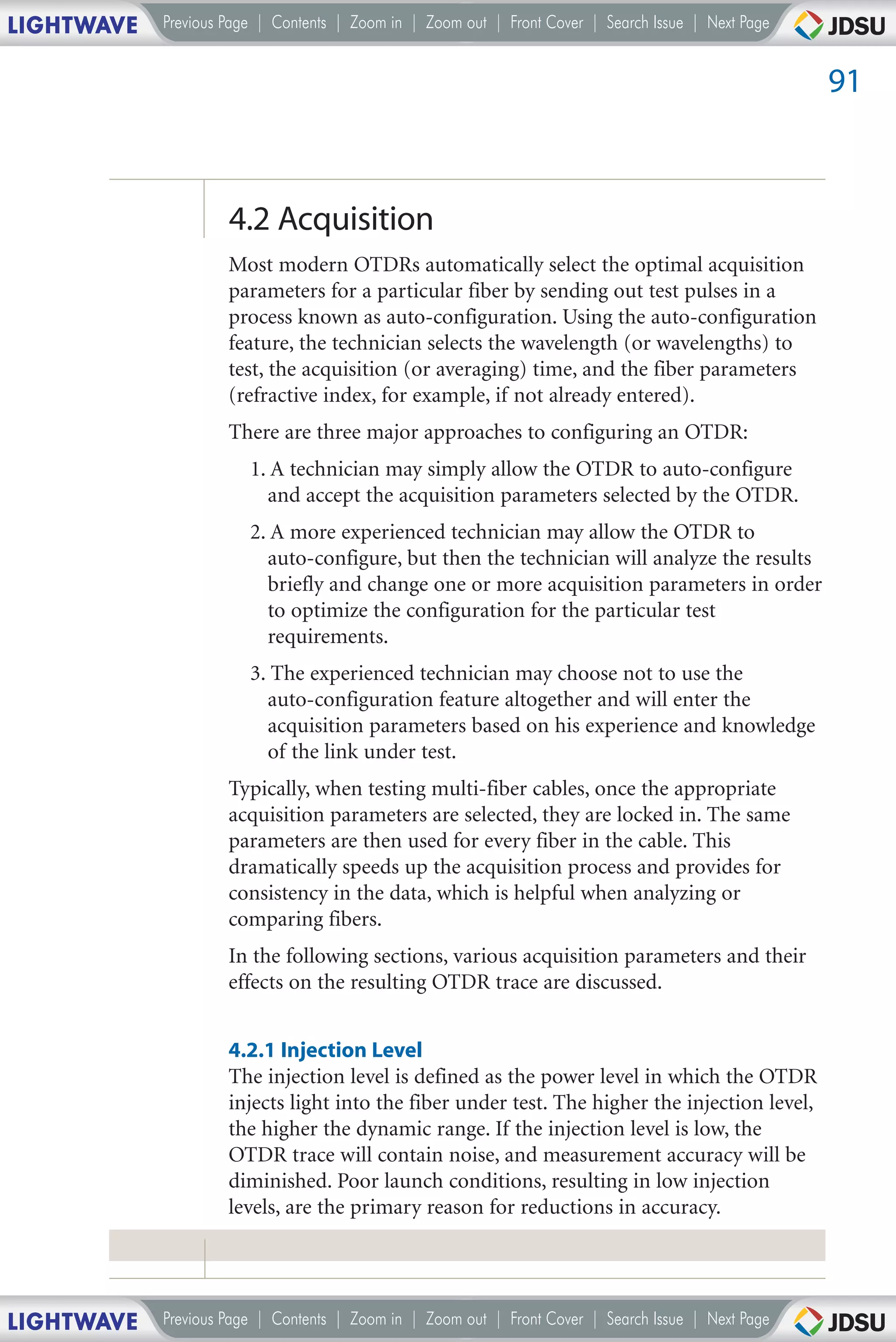

4.3.7 Optical Return Loss

High-performance OTDRs can automatically measure and report a

value for the total link optical return loss (ORL). A manual ORL

measurement capability is also provided in order to isolate the

portion of the link, which contributes the majority of the ORL.

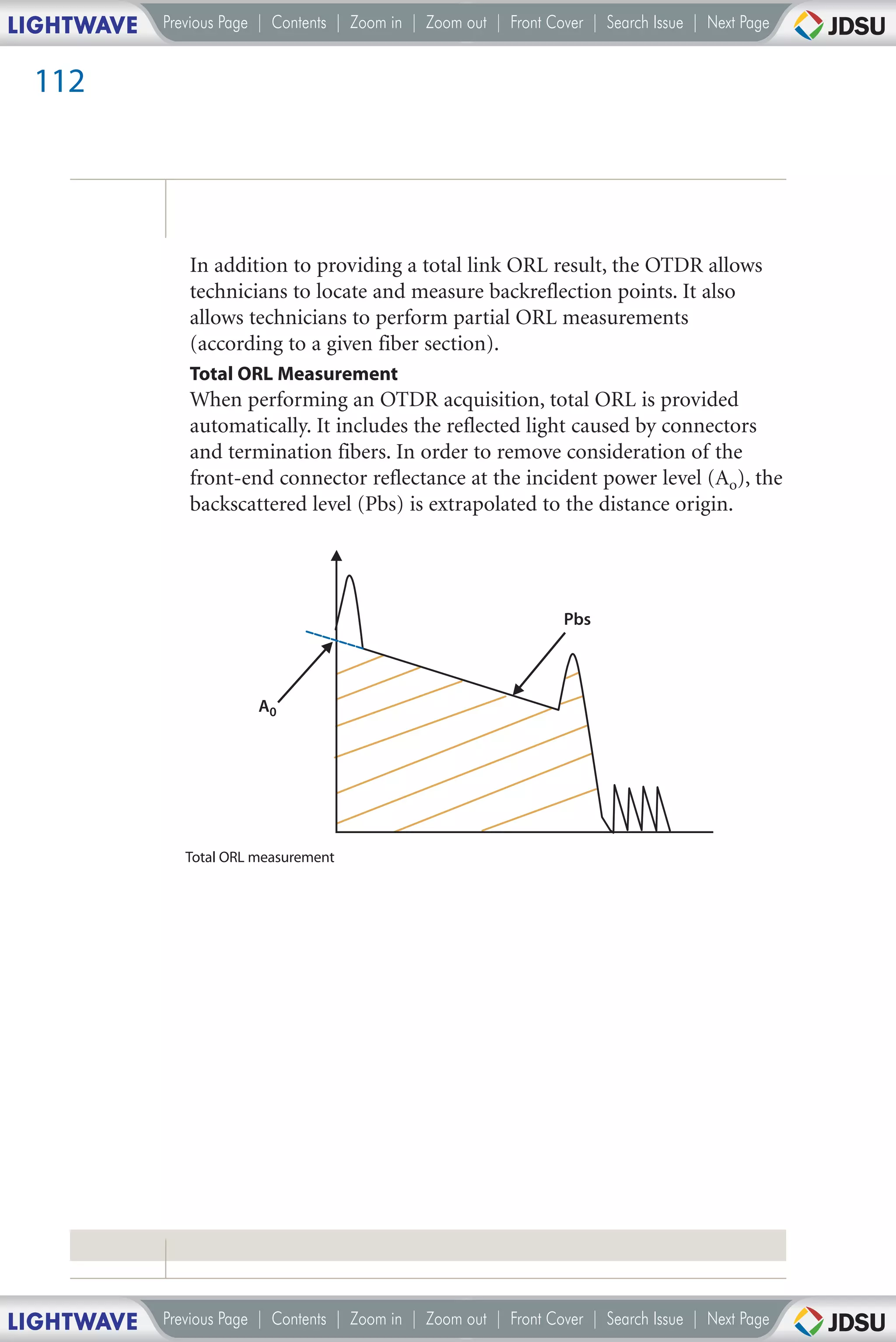

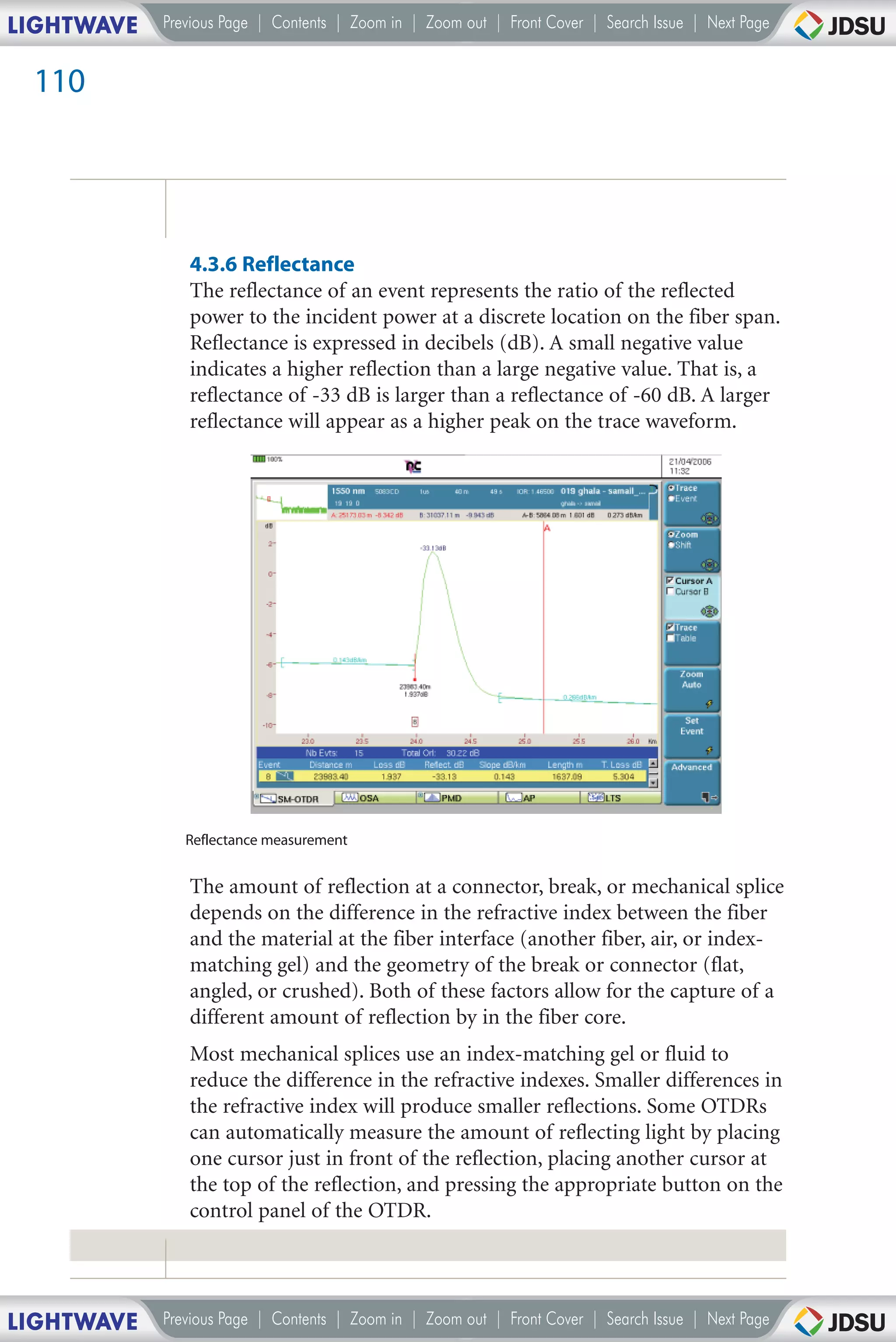

4.3.7.1 Measuring ORL with an OTDR

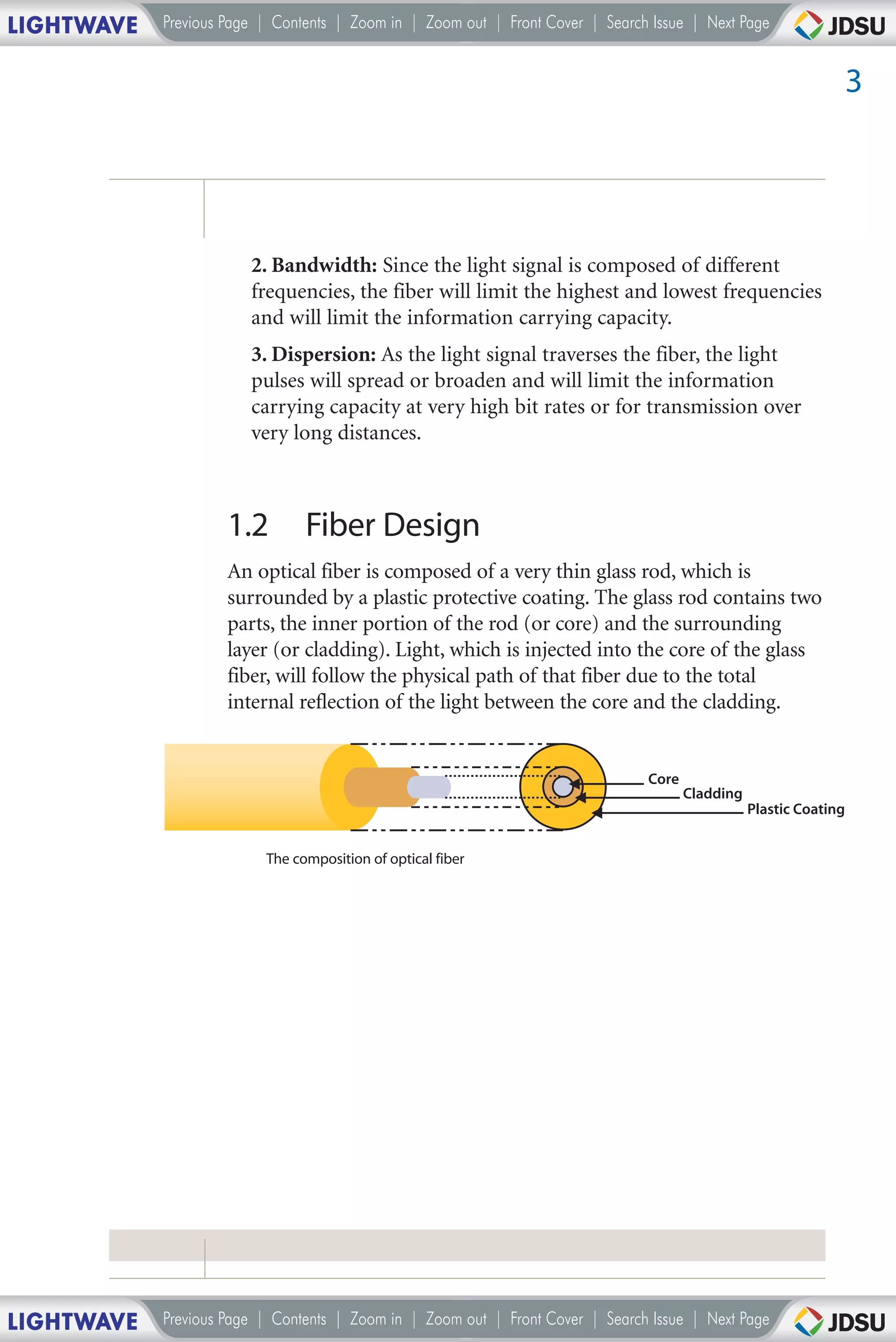

The light received by an OTDR corresponds to the behavior of

the reflected power along the fiber link according to the injected

pulsewidth. The integral of this power allows for the calculation

of the total back reflection and for the determination of the

ORL value.

ORL=10 Log [(P0x∆t)/(∫Pr(z)dz)]

Where Po is the output power of the OTDR, ∆t is the OTDR

pulsewidth, and ∫Pr(z)dz is the total backreflected and backscattered

power over the distance (partial or total).

ORL measurement of a fiber link

LIGHTWAVE Previous Page | Contents | Zoom in | Zoom out | Front Cover | Search Issue | Next Page](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/jdsubook-130331001905-phpapp01/75/Jdsu-book-120-2048.jpg)