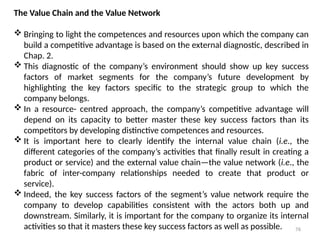

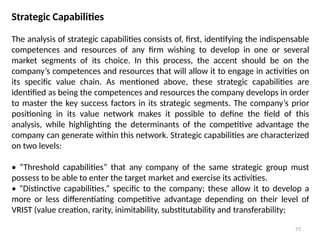

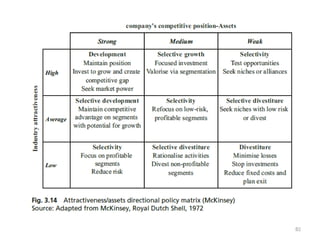

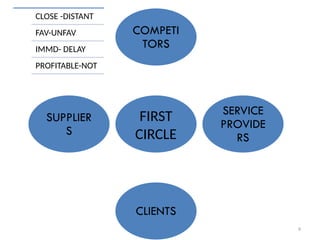

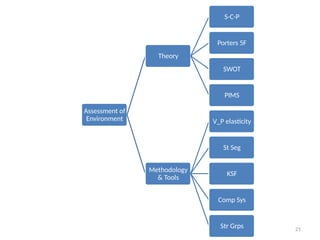

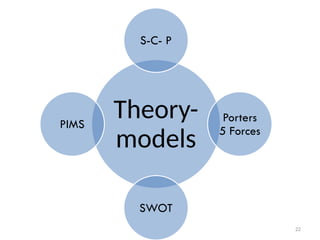

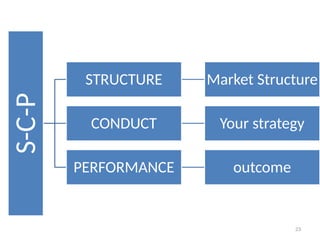

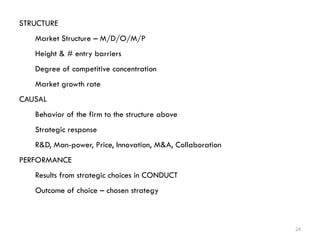

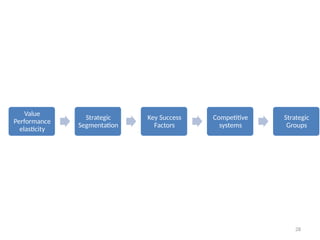

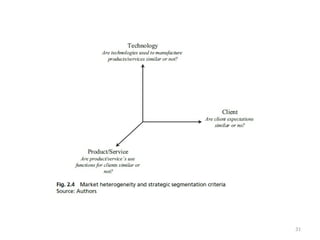

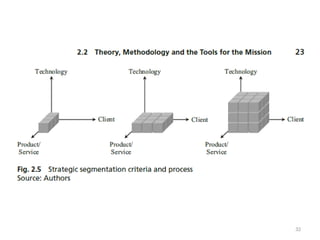

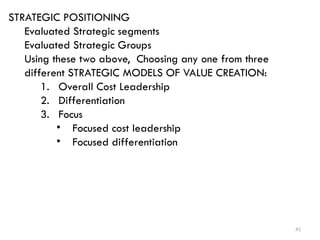

The document provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary business models and strategic consultancy missions aimed at assessing the business environment, competitive positioning, and growth strategies. It outlines methodologies for analyzing market structures, identifying key players, and evaluating strategic options such as blue ocean strategies and divestment. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of understanding value/performance elasticity and strategic segmentation in the context of business performance and market opportunities.

![57

Which markets would be receptive to my company’s current offer? Do these

target markets possess many and high entry barriers or do they operate in an

open and integrative format such as a platform environment? How should my

company adapt its offer in this respect? Which new markets will allow my

company to deploy my company’s competences and resources and develop a

new offer?

Consistent with the company’s intention to grow, a fourth series of missions

seeks to analyze the environment to detect new markets and client segments

and facilitate their emergence. Here, analyzing the environment serves to

identify new competitive spaces, or “blue oceans” as defined by W. Chan Kim

and Renée Mauborgne. In this case, consultants need to adopt a

“reconstructionist approach” whose objective is to “help companies

systematically reconstruct their industries and reverse the [environment]

structure-strategy sequence in their favor”2 (p. 74). Building on a scenario-

based or future anticipation approach, consultants help CEOs and top managers

to define the boundaries of these new high potential markets and segments. To

this end, they must also formalize the strategic actions required to give form

and reality to these new competitive spaces. Here, the key questions are:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit1-250125093547-8eb07778/85/Introduction-to-contemporary-Business-Models-57-320.jpg)