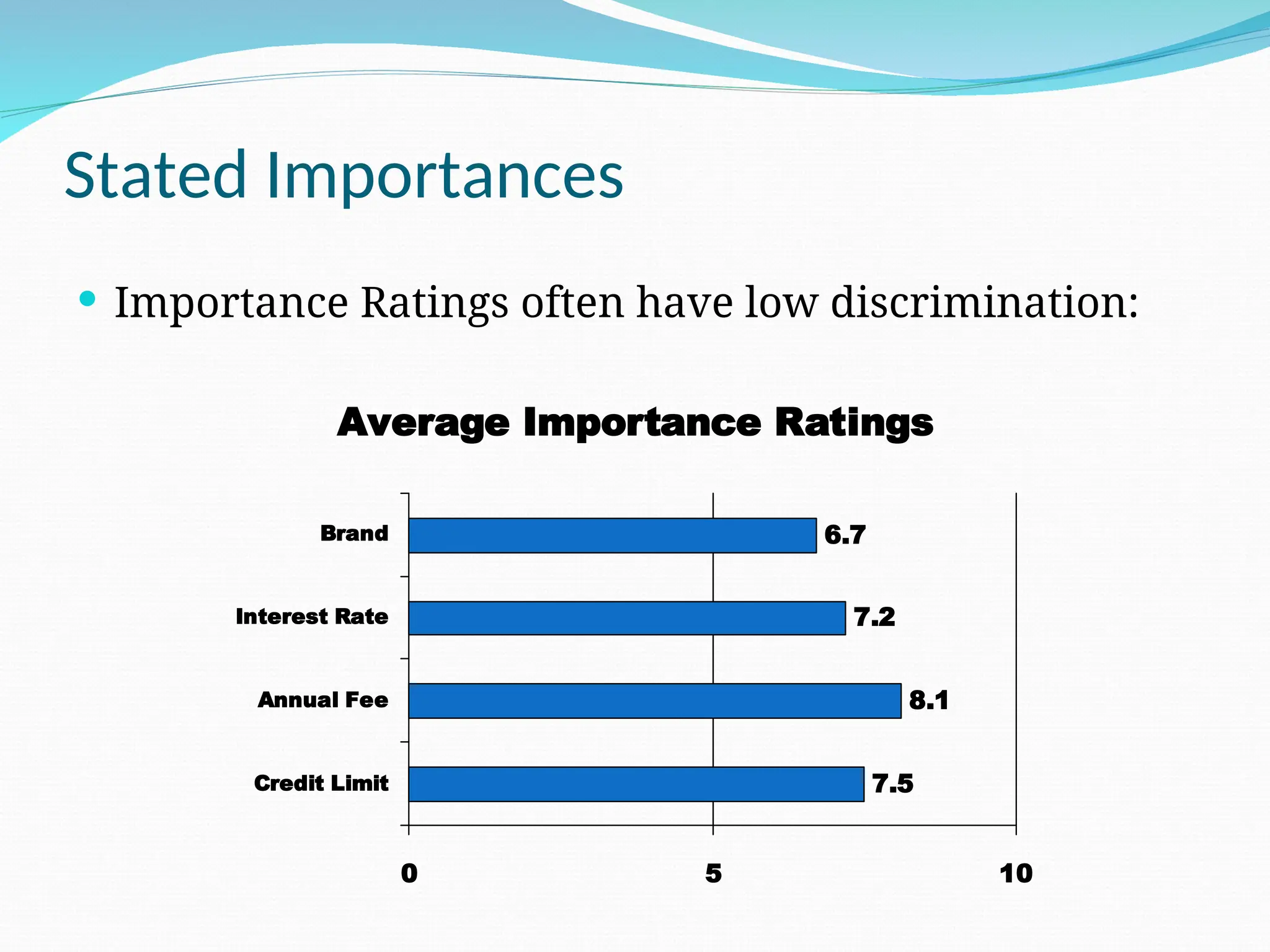

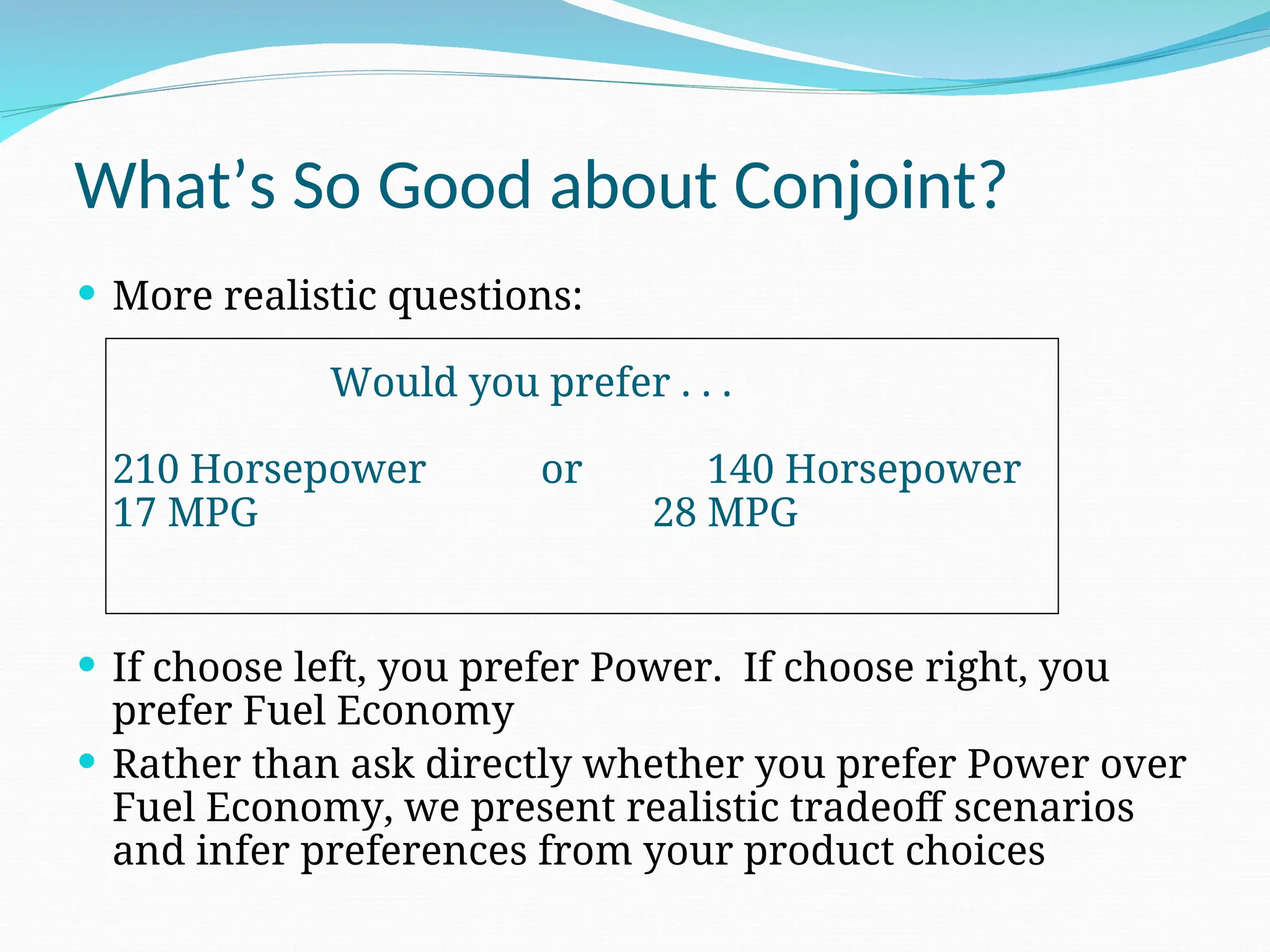

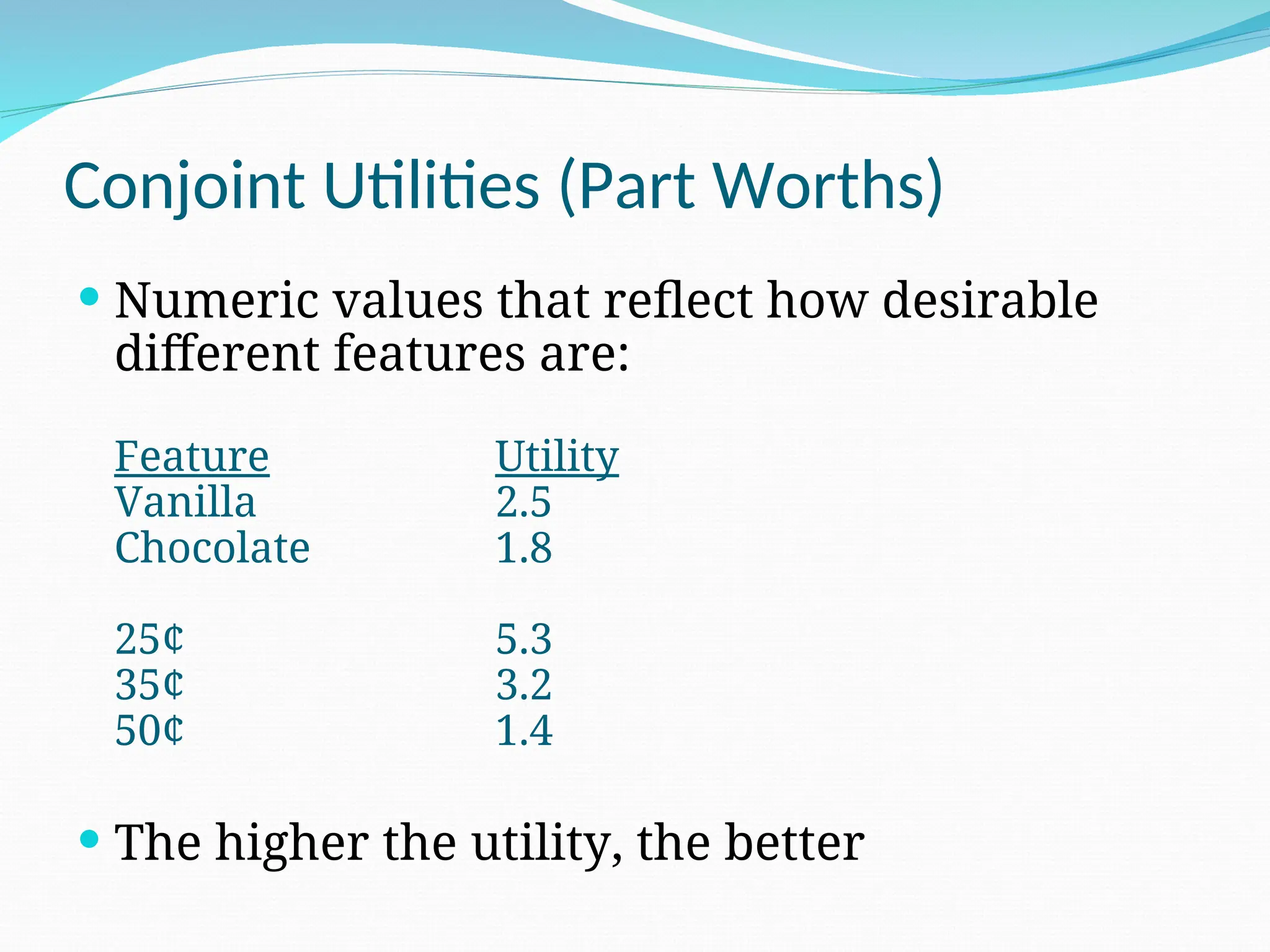

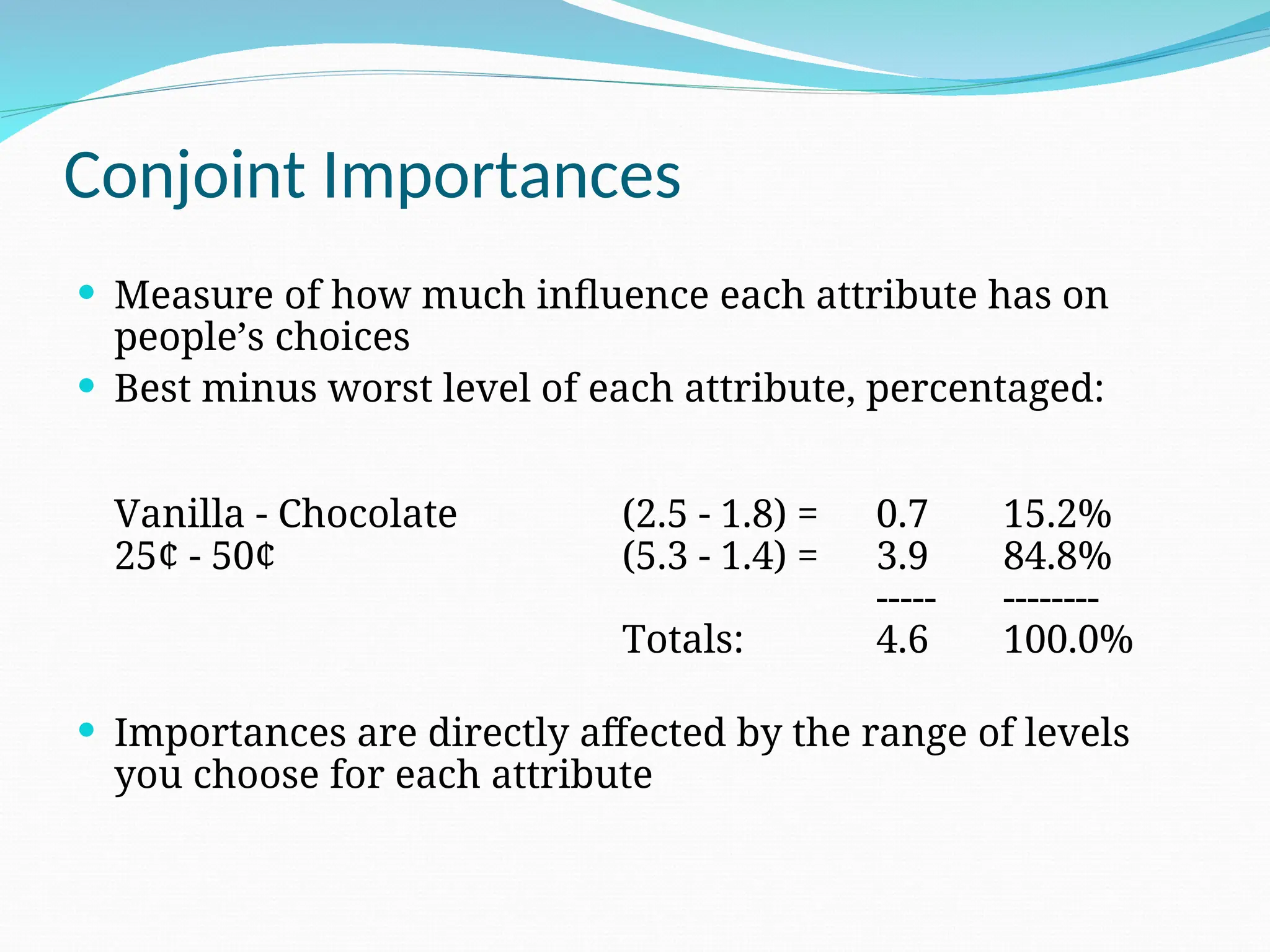

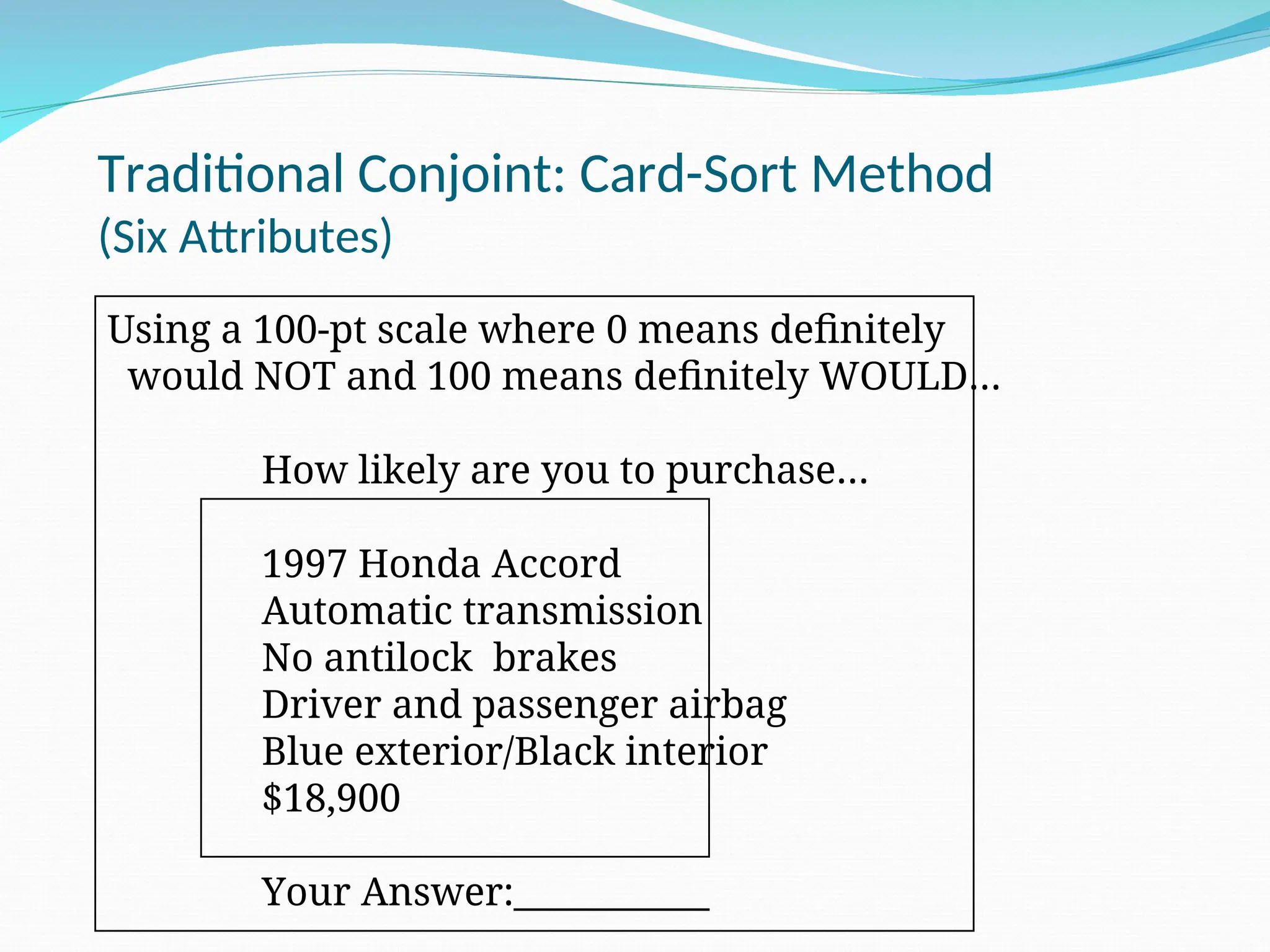

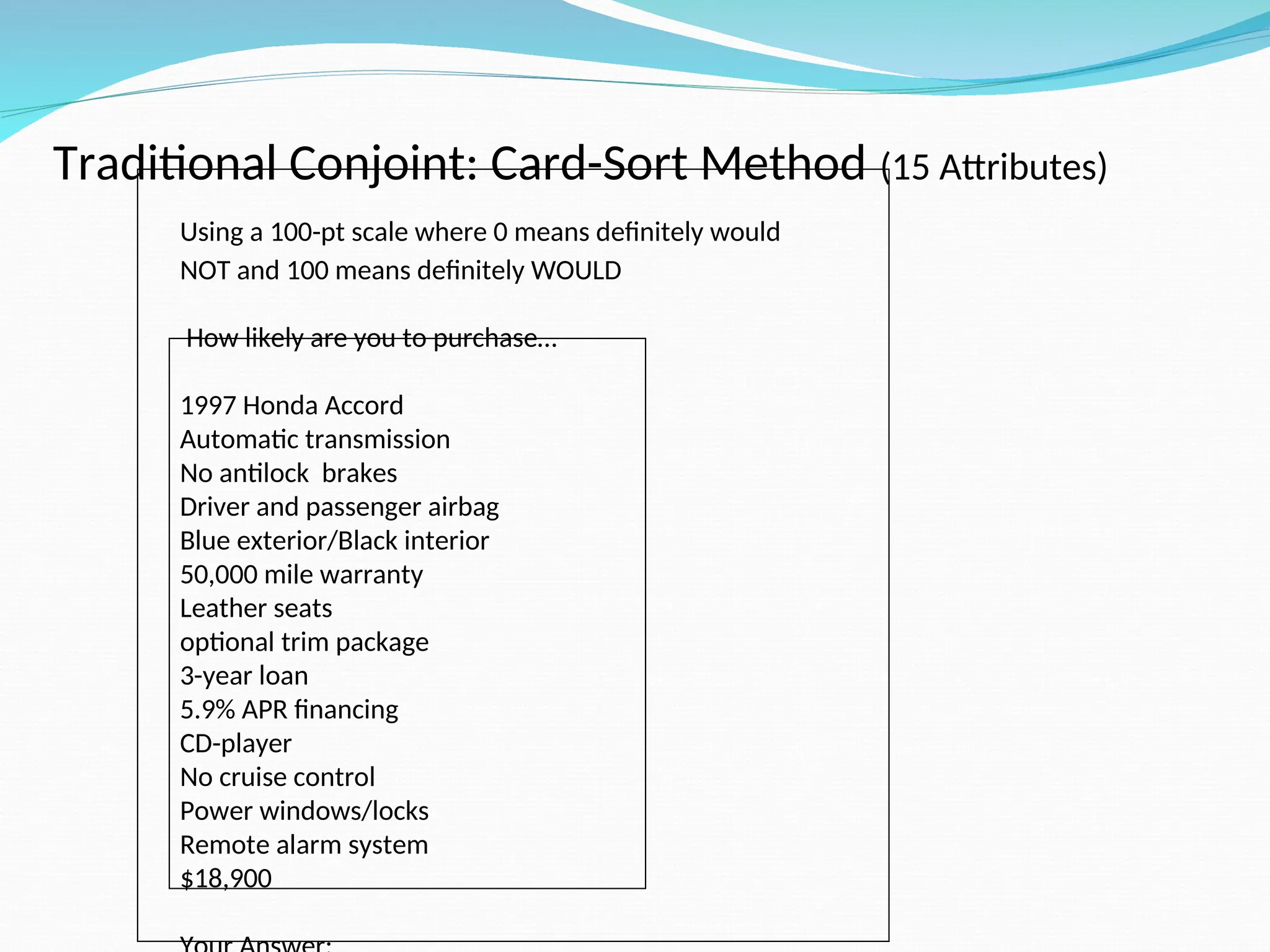

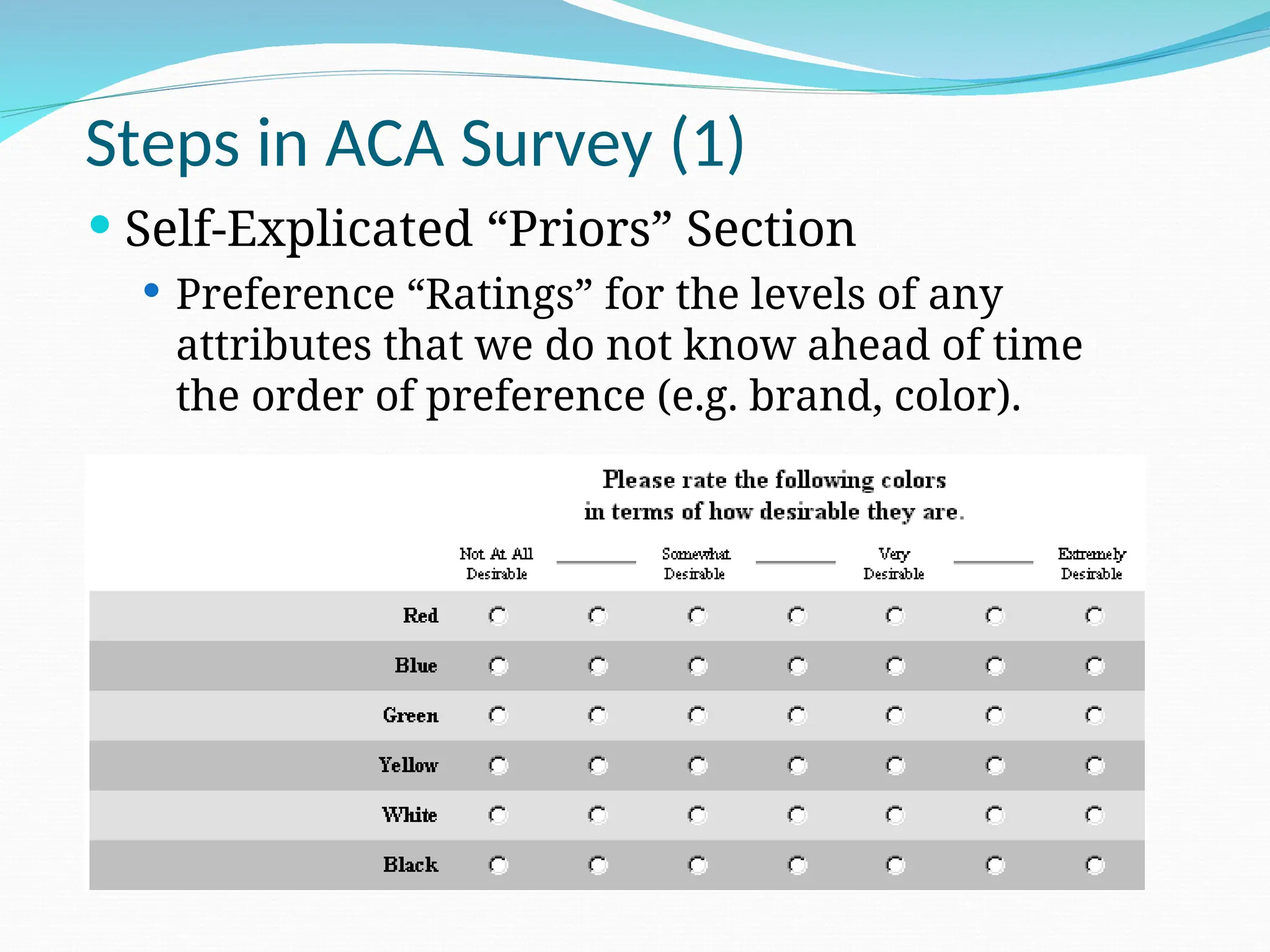

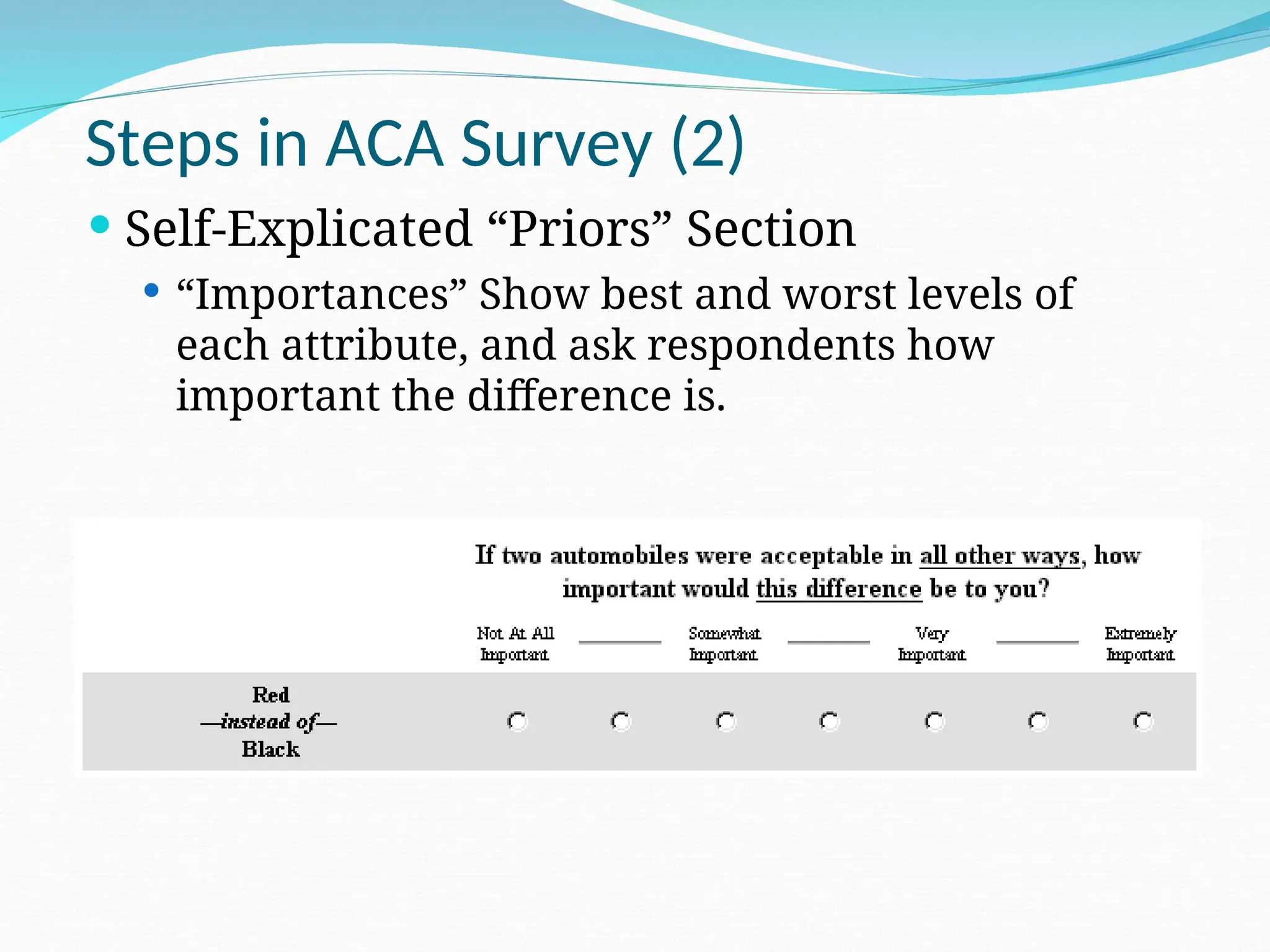

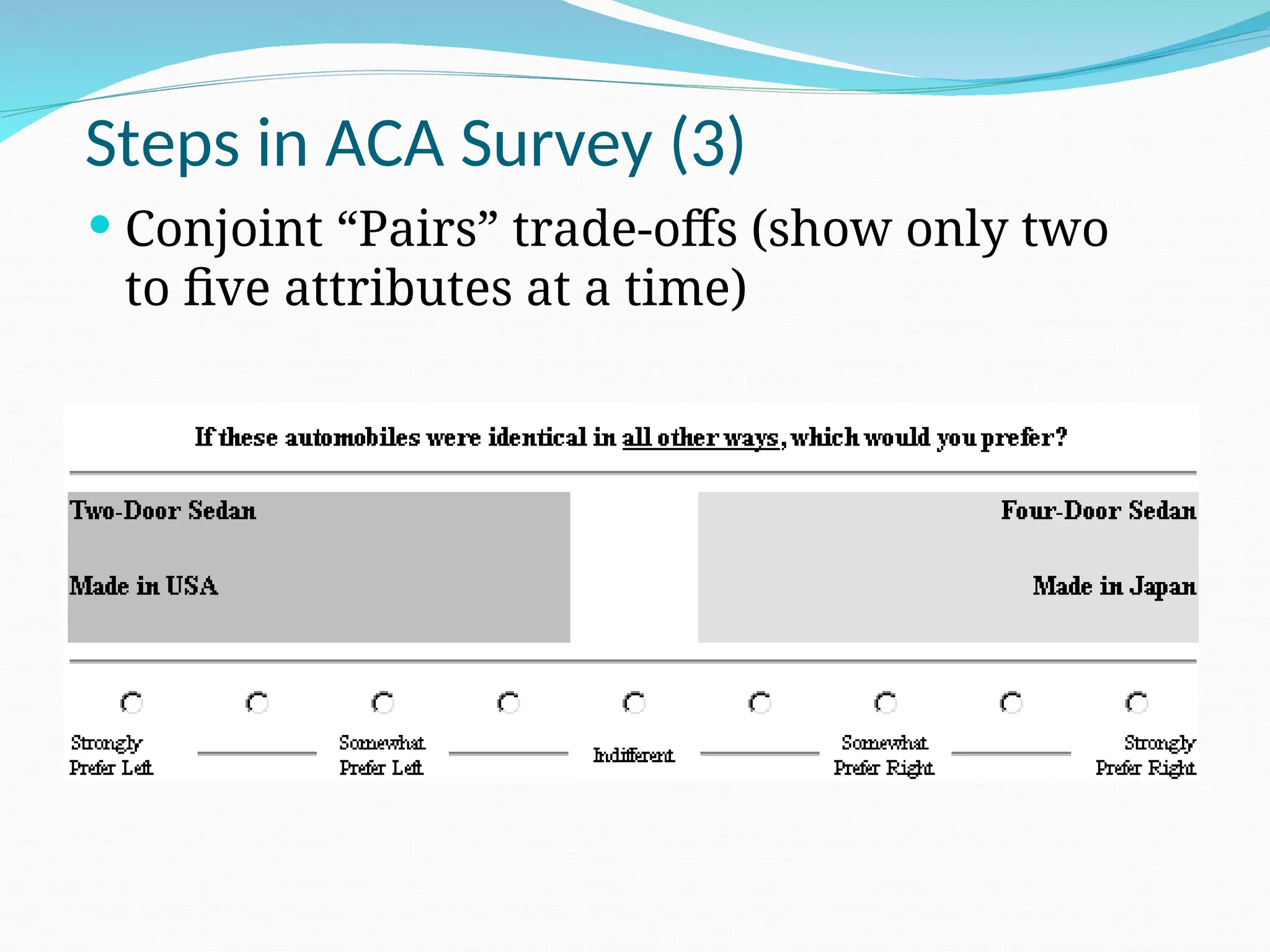

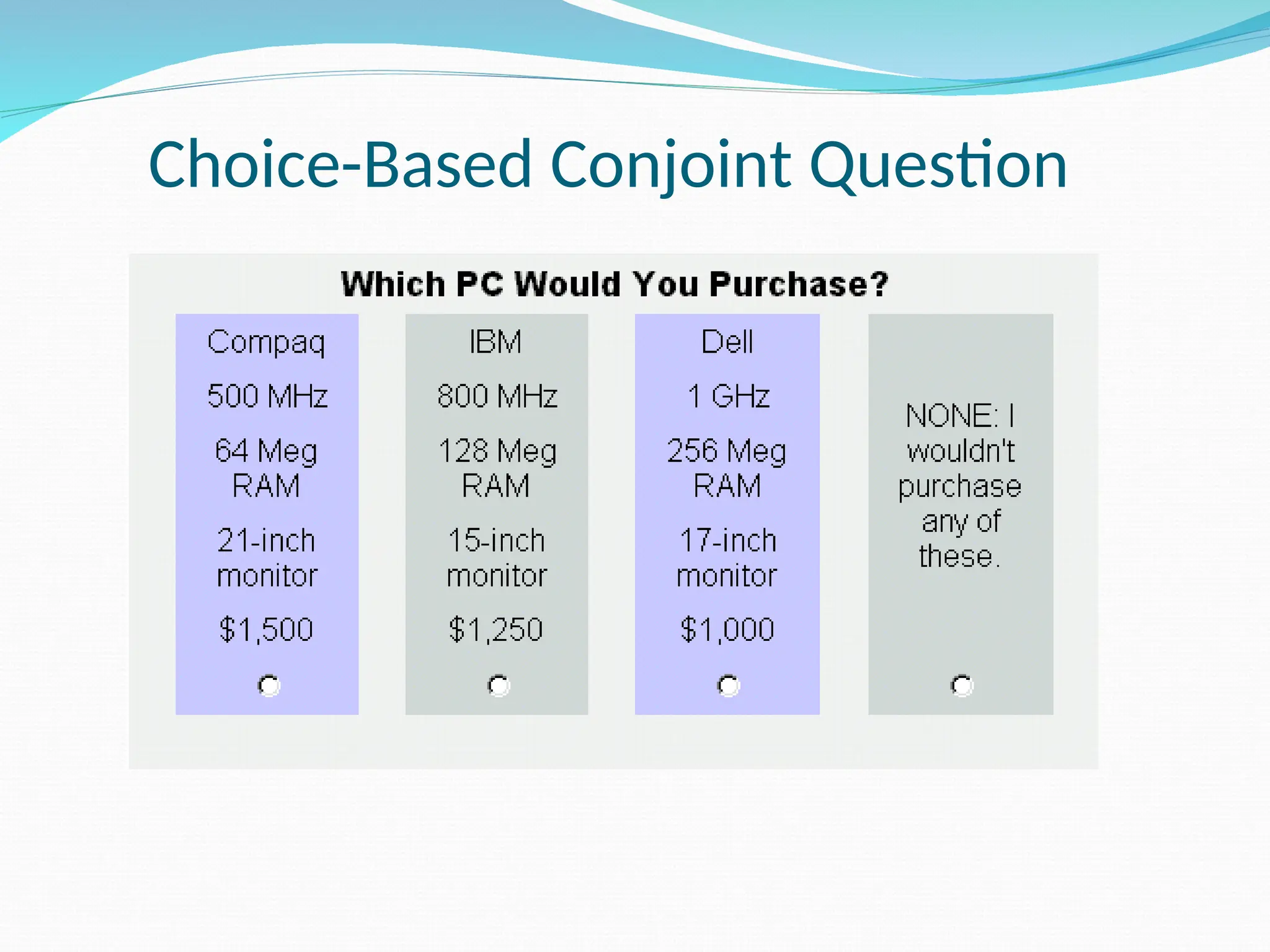

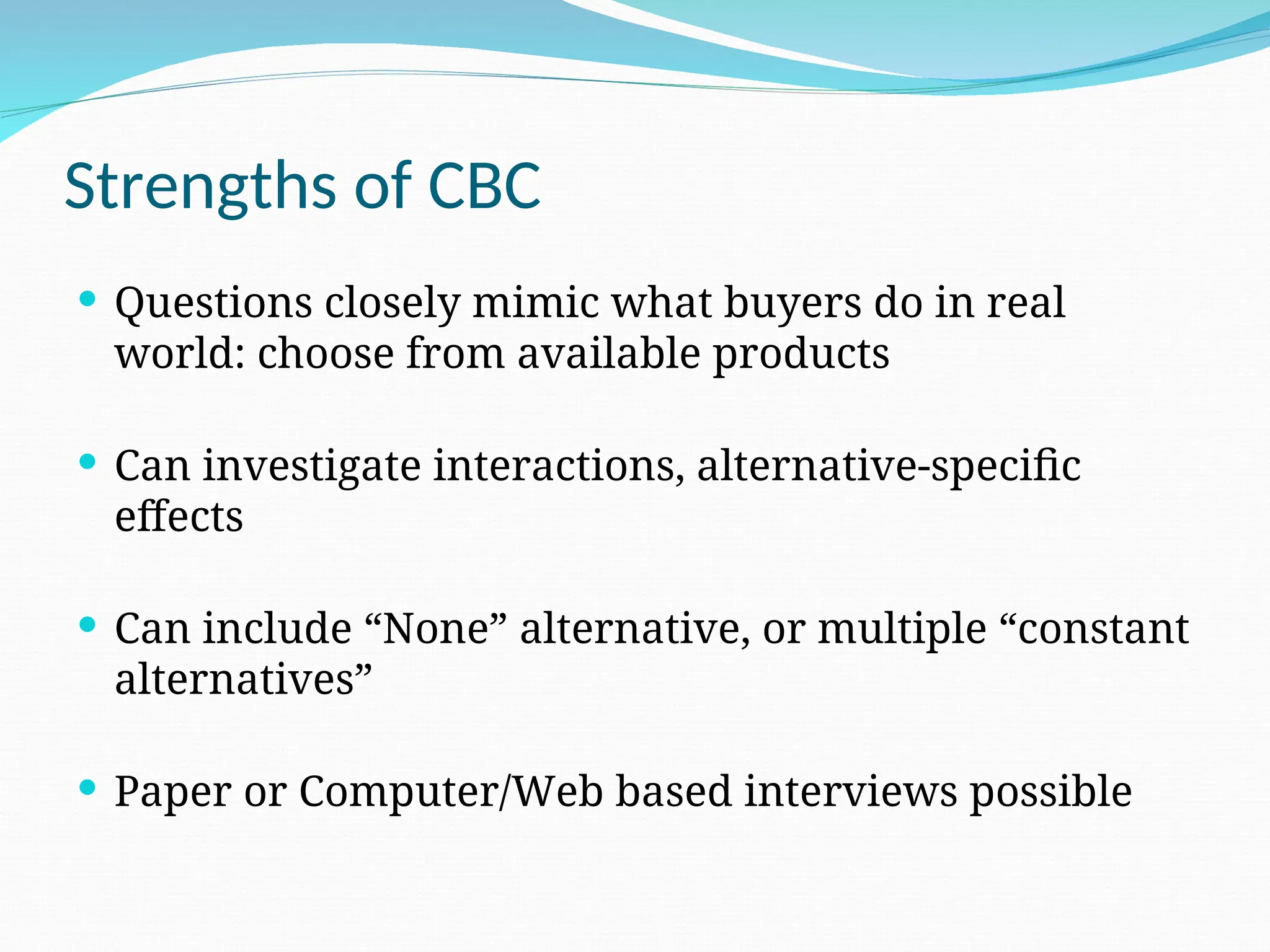

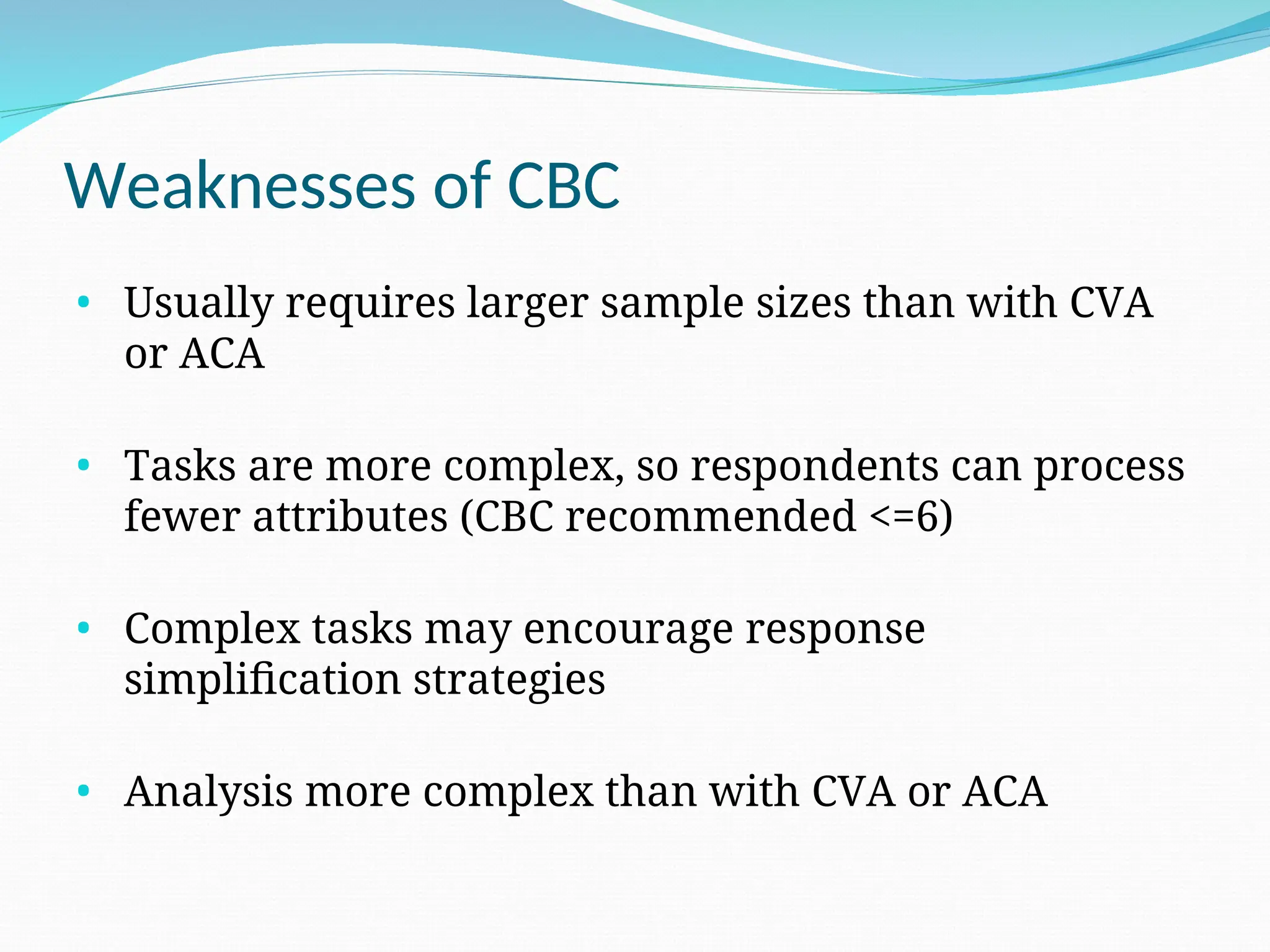

The document provides an overview of conjoint analysis, a market research technique used to gauge how buyers value different features of a product or service. It discusses the variations in approaches including traditional full-profile conjoint, adaptive conjoint analysis (ACA), and choice-based conjoint (CBC), each with their own strengths and weaknesses. The document emphasizes the importance of asking realistic trade-off questions to uncover consumer preferences effectively.