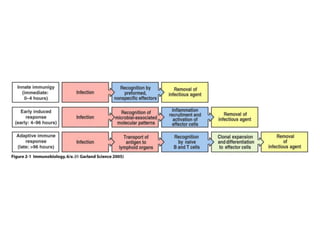

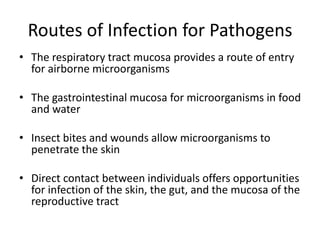

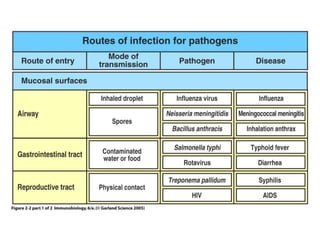

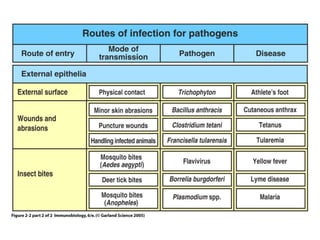

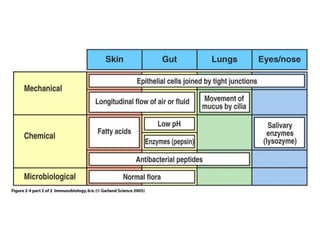

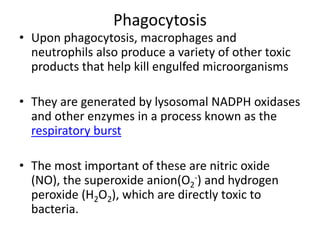

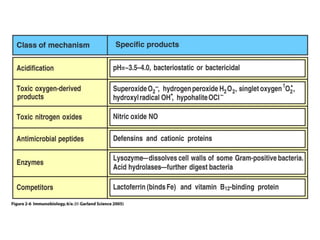

This document discusses innate immunity and the body's first lines of defense against infection. It describes how the epithelial surfaces provide mechanical, chemical and microbiological barriers. Phagocytes like macrophages and neutrophils play a key role by recognizing, ingesting and destroying pathogens. These cells use mechanisms like phagocytosis and generation of toxic molecules to kill invading microbes. However, some pathogens have evolved ways to avoid destruction by innate immune defenses.