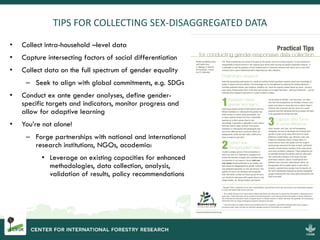

The document discusses the importance of gender-responsive climate policies in addressing climate change, particularly in the forestry sector, which significantly contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions. It highlights the existing gender inequalities and the lack of attention to gender in climate policy and action, emphasizing the necessity for data collection and gender-specific indicators to improve outcomes for women and enhance environmental performance. The document advocates for leveraging existing local knowledge and forming partnerships to develop better methodologies for understanding and addressing gender issues in climate initiatives.