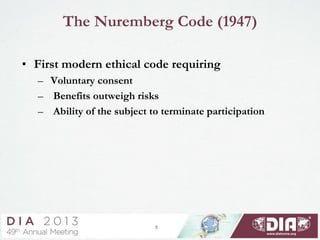

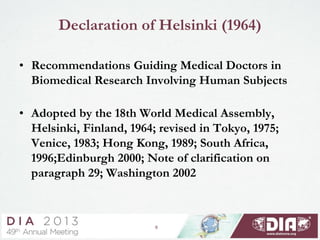

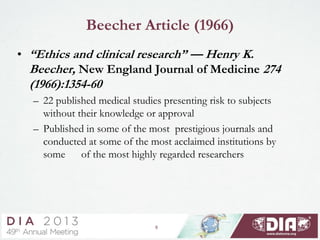

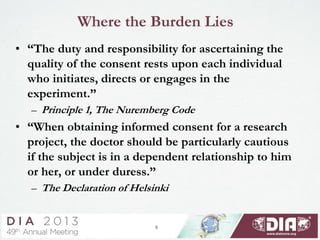

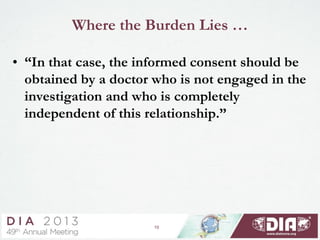

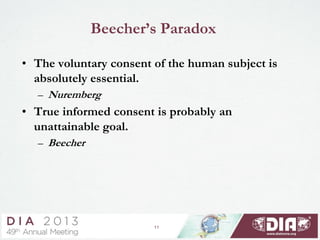

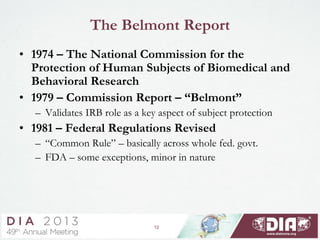

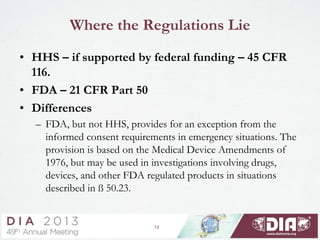

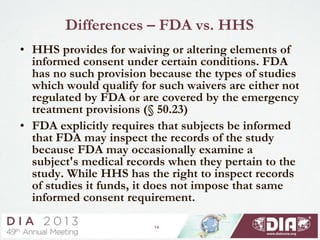

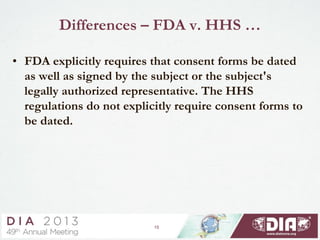

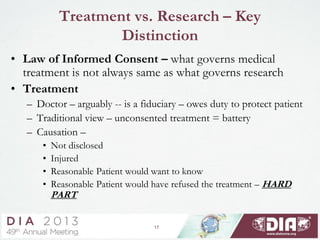

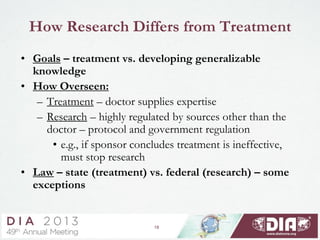

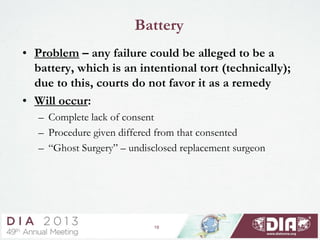

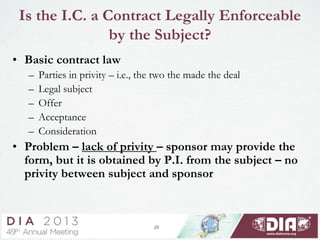

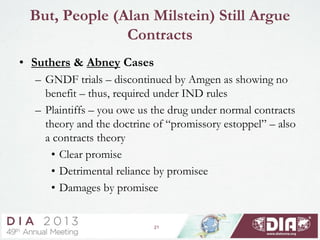

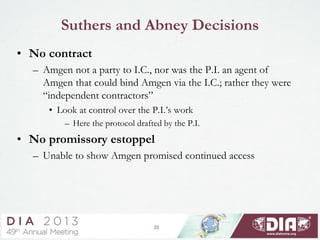

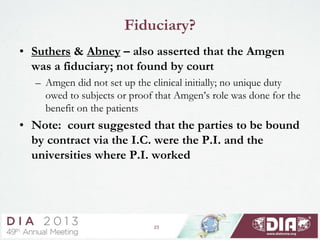

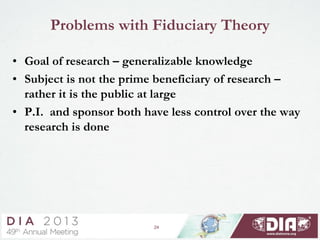

This document provides an overview of the historical background and legal framework surrounding informed consent in clinical research. It discusses key documents that have shaped ethics standards, including the Nuremberg Code, Declaration of Helsinki, and Belmont Report. The document examines different legal theories for how informed consent is understood, such as through a contractual framework, fiduciary duty, or platitude. It notes challenges to treating informed consent solely as a legal contract given lack of privity between subjects and sponsors. The document also distinguishes informed consent standards for research versus medical treatment.