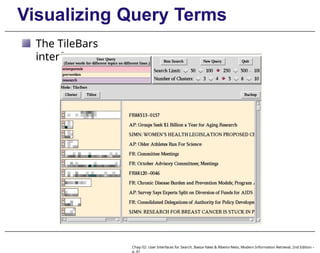

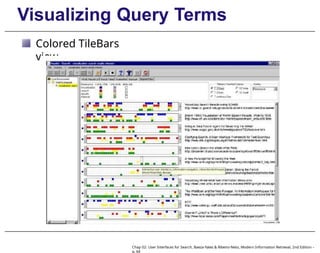

Chapter 2 of 'Modern Information Retrieval' discusses the design and evaluation of user interfaces for search systems, focusing on how users interact with search interfaces based on their tasks and expertise. It emphasizes the importance of aiding users in formulating queries, navigating results, and understanding their information needs, while also distinguishing between information lookup and exploratory search. The chapter highlights key models of the search process, user strategies in query formulation, and the impact of interface design on search effectiveness.