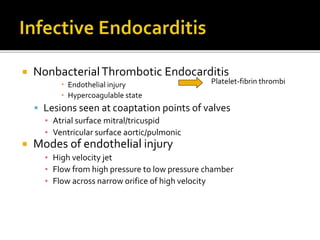

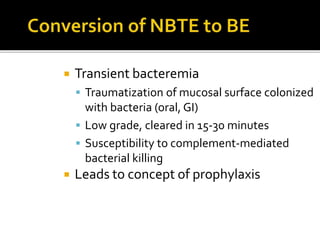

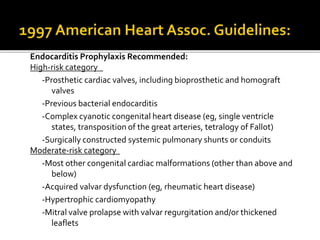

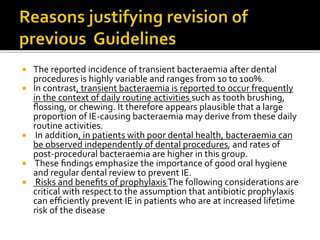

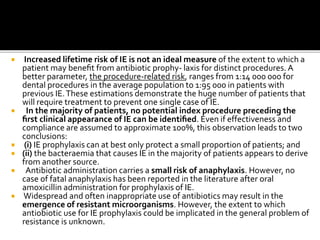

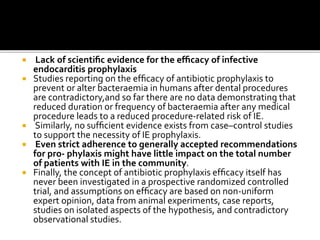

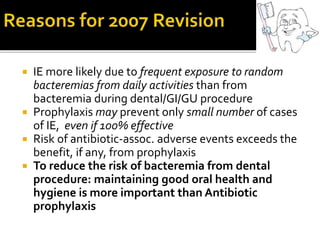

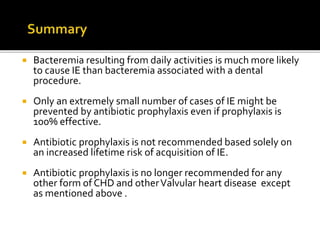

Infective endocarditis is a microbial infection of the heart that has proven difficult to treat as its incidence and mortality have not decreased in recent decades despite medical advances. It presents in various forms depending on factors like the microorganism, underlying heart condition, and patient characteristics. Guidelines are often based on expert opinion due to the low incidence of the disease and lack of randomized trials.