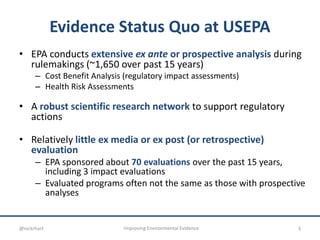

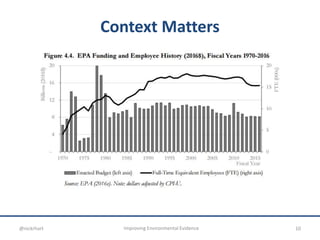

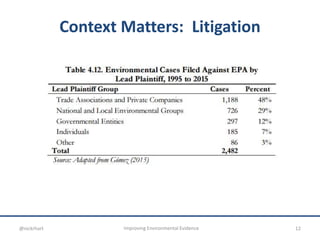

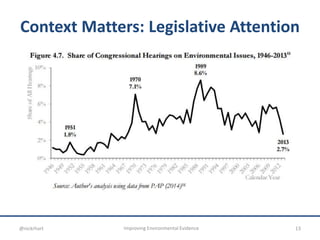

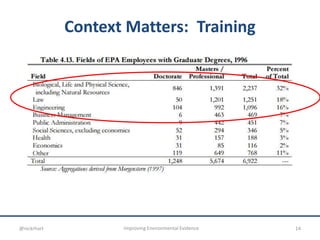

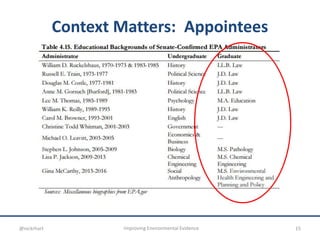

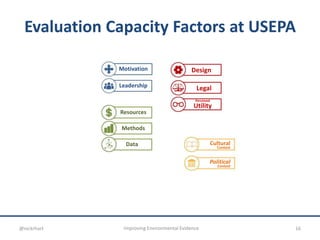

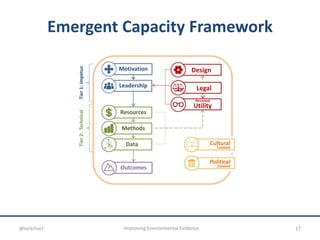

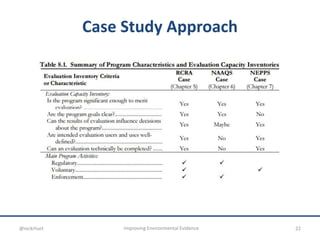

The document discusses evaluation capacity at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), highlighting barriers and facilitators to conducting effective evaluations within its programs. Despite the EPA's extensive resources and regulatory framework, it performs limited evaluations compared to the number of rulemakings. The paper suggests strategies for improving evaluation capacity, emphasizing the need for learning processes and broader infrastructure to better support evaluative practices.